The Role of Public Opinion in Supreme Court Confirmations

The Role of Public Opinion in Supreme Court Confirmations1

The judiciary is the branch of the federal government most insulated from the public. Unlike the president or Members of Congress, federal judges do not have to stand for election—they are appointed to the bench and serve lifetime terms. Justices on the Supreme Court do not even worry about securing a promotion to a higher court. This leaves them largely unconstrained in their decision-making, which ultimately reaches into some of society’s most important and controversial policy areas.

Judicial independence has obvious advantages. It leaves the justices free from improper influence, free to make impartial decisions, and free to protect the rights of unpopular minorities. “Too much” independence, however, could work against the democratic principle of popular rule. If Supreme Court justices frequently overturn the actions of the elected branches or issue decisions that are opposed by the people, concerns will inevitably be raised that the Court is thwarting public will and undermining the responsiveness of the American political system.

Scholars of political science have long debated whether Supreme Court justices are influenced by public opinion (Flemming and Wood 1997; Giles, Blackstone, and Vining 2008; Mishler and Sheehan 1993). If they are, concerns about the counter-majoritarian nature of the Court would be mitigated somewhat. There is another, but less noticed, way in which these concerns could be allayed: if the public could influence not only how the justices vote, but who sits on the Court in the first place. The decision to seat a justice is in the hands of the president and the Senate, but electoral incentives, particularly for senators, can tie the Court back to the public. Senators must eventually stand for re-election, which gives them an incentive to pay close attention to the views of their constituents, especially when casting a high profile roll call vote for or against a nominee to the Supreme Court.2

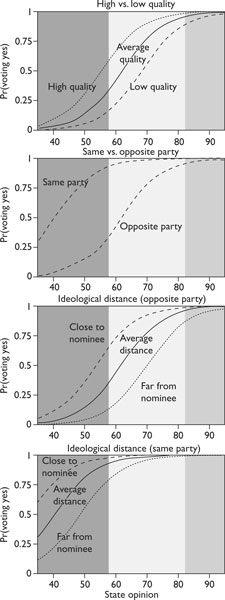

In this chapter, we ask whether public opinion influences the votes of individual senators when they vote on Supreme Court nominees, and thus whether it affects who ultimately sits on the Court. Using national public opinion surveys and advances in estimating opinion at the state level, we generate measures of state-level public support for 11 recent nominees. With the help of regression analysis, we then see if constituent opinion is a significant predictor of senators’ confirmation votes. We find that it is, even when accounting for well-known influences on roll call voting, such as partisanship and ideology. Our results establish a strong and systematic link between constituent opinion and voting on Supreme Court nominees. These results have important implications for confirmation politics specifically and more generally for larger debates about representation and responsiveness in legislatures.

Linking Constituent Opinion and Confirmation Votes

One might wonder whether the public can actually play the meaningful role in confirmation politics that we suggested above. There are three elements that are necessary to create a meaningful connection between the American public and the identity of those individuals who sit on the Supreme Court: knowledge, salience, and attention.

First, does the public know enough to play a role in confirmation politics, particularly with respect to senatorial voting? It is commonly thought that the American public has only very minimal knowledge of the Supreme Court. Indeed, surveys often find that large majorities of respondents cannot name a single justice. We now know that this conclusion is overstated, if not simply incorrect. Citizens tend to know about court decisions that affect them or issues they care about. They are also able to able to answer basic knowledge questions about the Court as an institution, such as the method by which justices are selected, the length of their terms, and whether or not the Court has the “last say” when it comes to interpreting the Constitution (Gibson and Caldeira 2009a).

Of course, general knowledge is less important than whether citizens actually pay attention to Supreme Court nominations—in fact they do. By the time a nominee comes up for a roll call vote, most Americans can say where they stand on her nomination. For instance, in the days prior to the confirmation votes of Justices Clarence Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito, 95% and 88% of survey respondents, respectively, held an opinion either for or against confirmation (Gibson and Caldeira 2009c; Gimpel and Wolpert 1996). Importantly, these opinions appear to be reasonably well developed. Research shows that they are shaped by a survey respondent’s ideology, partisanship, and policy preferences as well as the whether the respondent views the nominee as having the characteristics of a good judge (Gibson and Caldeira 2009a). The public’s views on nominee confirmation seem connected to the very same influences as opinion on many other political issues from voting to policy support.

The second element is salience: if the public did not care about confirmation votes, then lawmakers might not pay attention to their constituents’ views. However, many Americans do care about such votes. For example, during the Alito nomination, 75% of Americans thought it important that their senators vote “correctly” (Gibson and Caldeira 2009a). Using 1992 Senate election data, Wolpert and Gimpel (1997) showed that voters nationwide factored their senator’s confirmation vote into their own vote choice. Such findings suggest that Americans know far more about the Court, pay far more attention to confirmation politics, and hold their senators far more accountable for confirmation votes than has often been assumed.

Finally, the third element is attention: do senators monitor and care about what the public thinks? Theories of legislator responsiveness to constituent opinion would suggest that the answer is “yes.” While the goals of Members of Congress are multifaceted, the desire for re-election has long been established as a powerful driver, if not the primary driver, of congressional behavior (Mayhew 1974). Although six-year terms provide senators with greater insulation than representatives, a re-election-minded senator will constantly consider how his votes, particularly highly visible ones, may affect his approval back home. While the outcomes of many Senate votes, such as spending bills or the modification of a statute, are ambiguous or obscured in procedural detail, the result of a vote on a Supreme Court nomination is stark: either the nominee is confirmed, allowing her to serve on the nation’s highest court, or she is rejected, forcing the president to name another candidate. In this process, note Watson and Stookey (1995, 19), “there are no amendments, no riders and [in recent decades] no voice votes; there is no place for the senator to hide. There are no outcomes where everybody gets a little of what they want. There are only winners and losers.” Accordingly, a vote on a Supreme Court nominee presents a situation in which a senator is likely to consider constituent views very carefully.

Indeed, history contains ominous warnings for senators who ignore what their constituents want. In 1991, Senator Alan Dixon of Illinois was one of only 11 Democrats who voted for the confirmation of Clarence Thomas, who was narrowly confirmed by a vote of 52 to 48. The next year, Carol Moseley Braun, despite being virtually unknown, defeated Dixon in the Democratic primary, principally campaigning against his vote to confirm Thomas (McGrory 1992). That same year, Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, a Republican at the time, nearly lost his Senate seat when liberal women’s rights organizations mobilized to defeat him after he voted to confirm Thomas.

Even when an unpopular vote does not lead to immediate retribution by the voters, it can still arise as a campaign issue years later. For instance, in a bid to unseat Specter in the 2004 Republican primary, challenger Pat Toomey invoked Specter’s vote against Robert Bork 17 years earlier. Specter was one of only six Republican senators to cast a vote against Bork, a nominee of President Reagan who was defeated after a highly combative nomination fight between, on one side, the Republican administration of President Reagan and its Republican allies in the Senate, and Democratic senators on the other.

Of course, senators can only follow public opinion if they know what the public thinks. How do senators take the pulse of their constituents on Supreme Court nominees? Public opinion polls help inform senators, as do more direct forms of communication such as phone calls and letter writing. Interest groups also play an important role both in shaping constituency preferences and informing senators of these preferences: “Interest groups attempt to mold senators’ perceptions of the direction, intensity and electoral implications of constituency opinion” (Caldeira and Wright 1998). They organize letter-writing campaigns and encourage the public to contact their senator. As part of their lobbying efforts, interest groups also directly convey information about the direction and intensity of constituent opinion. It is thus likely that most senators will have a good idea of where their constituents stand when voting on a Supreme Court nominee.

Given this, it is no surprise that presidents often “go public” in the hope of shifting public opinion on their nominees (Johnson and Roberts 2004). For example, in 1969, Richard Nixon’s White House actively worked to shift public opinion on Clement Haynsworth and Ronald Reagan’s White House launched a “major (though largely unsuccessful) public relations offensive to build support for [Robert Bork]” in 1987 (Maltese 1995, 87–88). Indeed, “one of the crucial elements in confirmation strategies concerns how public opinion will be managed and manipulated” (Gibson and Caldeira 2009c).

Measuring Constituency Opinion

While there are reasons to believe that constituent opinions matter when it comes to confirmation votes it has been very difficult for scholars to evaluate this prediction. The reason is straightforward: most polls that gauge public support for a Supreme Court nominee are conducted by national survey organizations and are only designed to measure public sentiment at the national level. These polls do not sample enough respondents from each state to make cross-state comparisons possible or even to say anything meaningful about public opinion in a given state. Indeed, an average-sized national survey is likely to include just a few people from smaller population states, such as New Hampshire, Vermont, and Wyoming.

Fortunately, we are able to overcome this limitation by using a new methodological technique. Our first step was to gather national survey data. We began by seeing how much polling data exists on Supreme Court nominees, going back as far as possible. To accomplish this, we searched the Roper Center’s iPoll electronic archive, which is a terrific resource for finding survey data on almost any topic.3 As it turns out, while Supreme Court nominations have been high salience events throughout U.S. history, not until very recently were polls systematically conducted on Supreme Court nominees. Indeed, we could not find a single poll conducted on the nomination of Justice Antonin Scalia—a fact that is very surprising considered in hindsight, given Scalia’s rather notable and controversial tenure on the Court.

Our goal was to estimate support for confirmation for every state-nominee pair—that is, state-level opinion for each of the 50 states for every nominee. All of these polls we found, however, were conducted on the national level, so we are still left with the problem of how to develop accurate state-level estimates of public opinion on the nominees. To accomplish this, we use statistical models to translate the data from the national polls into state-level estimates. Specifically, we use a technique known as multi-level regression and poststratification or MRP (Gelman and Little 1997; Park, Gelman, and Bafumi 2006). While the underlying method relies on fairly sophisticated statistical techniques, the idea behind MRP is fairly intuitive. Basically, this method uses the information we have in the survey data and from other sources to build an accurate picture of what is going on in each state. After all, in a survey, we do not just know how many people hold a certain opinion—we know which people hold that opinion. We know their demographic characteristics such as age and education. MRP makes use of this information in a particular way.

MRP proceeds in two stages. In the first stage, individual survey responses and regression analysis are used to estimate the opinions of different types of people. This is the “multilevel regression” part of MRP, which is a version of traditional regression analysis, except that the hierarchical nature of the data is explicitly modeled (for example, citizens are one level of analysis but citizens are grouped into different states, which are another level of analysis). These opinions are treated as being a function of individuals’ demographic and geographic characteristics. That is, we evaluate Americans’ support for a given nominee, or the “dependent variable” in MRP, as function of these characteristics, or the “independent variables.”