The Law of Arrest, Search, and Seizure

3

The Law of Arrest, Search, and Seizure

Applications in the Private Sector

Chapter outline

Constitutional Framework of American Criminal Justice

Arrest and Private Sector Justice

The Law of Citizen’s Arrest: The Private Security Standard

The Law of Search and Seizure: Public Police

The Law of Search and Seizure: Private Police

Challenges to the Safe Harbor of Private Security

Private Action as State Action

The Public Function of Private Security

Color of State Law: A Legislative Remedy

Constitutional Prognosis for Private Security

Introduction

Private policing, as noted in The Hallcrest Report II, plays an integral role in the detection, protection, and apprehension of criminals in modern society. Many interested sources deem it as the more responsive, efficient, and productive player in the administration of justice.1 The advantages of private sector justice are many and diverse.

To search WorldCat and find out where the Hallcrest Report II is in your area, go to http://www.worldcat.org/title/private-security-trends-1970-to-2000-the-hallcrest-report-ii/oclc/22892639.

Aside from its efficiencies and customer service orientation, private policing retains a strong procedural advantage in matters of constitutional oversight. As noted already, the typical constitutional protections that emanate in public policing matters, do not apply to private sector police. Naturally, business and industry prefer to deal with private sector justice since their own private police forces are not constrained by constitutional dimensions. As Professor William J. O’Donnell eloquently notes:

The growth of the private security industry is having an increasingly controversial impact on individual privacy rights. Unlike public policing, which is uniformly and comprehensively controlled by applied constitutional principles, private policing is not. Across the various jurisdictions, both statutes and case law have been used to curb some intrusion into privacy rights but this protective coverage is neither standardized nationally nor anywhere near complete. The net result is that some rather debatable private police practices are left to the discretion of security personnel.2

Constitutionally, the private sector has the upper hand because the extension of traditional police protections have never materialized. As the role of private security and private police develops, criminal defendants and litigants will clamor for increased protection. Already, defense advocates argue that Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendment–standards regarding arrest, search and seizure, and general criminal due process are applicable to private security, though most appeals courts reject these claims.3

The primary aims of this chapter are to provide a broad overview of the legal principles of arrest, search, and seizure in the private sector; to analyze the theoretical nexus between the private and public sector in the analysis of constitutional claims; and to review specific case law decisions, particularly at the appellate level. In addition, the chapter reviews the theory of citizens’ arrest, both in common and statutory terms. Finally, the research will assess the novel and even radical theories that seek to make applicable constitutional protections in the private sector including the following:

• The Significant Involvement Test

• The Private Police Nexus Test

• Common Law and Statutory Review of Private Security Rights and Liabilities

The precise limits of the authority of private security personnel are not clearly spelled out in any one set of legal materials. Rather, one must look at a number of sources in order to define, even in a rough way, the dividing line between proper and improper private security behavior in arrest, search, and seizure. Even traditional constitutional inquiry in the public sector can be complicated. So when these same obtuse principles are applied to private security, confusion can result. The Private Security Advisory Council recognizes this complexity:

In order to perform effectively, private security personnel must, in many instances, walk a tightrope between permissible protective activities and unlawful interferences with the rights of private citizens.4

Given that the criminal justice system is already administratively and legally beleaguered, it is natural for both the general public and criminal justice professionals to seek alternative ways for stemming the tide of criminality and carrying out the tasks of arrest, search, and seizure. Privatization is a phenomenon that surely will not dissipate.5 Private security has played an increasingly critical role in the resolution of crime in modern society.

Profound questions arise in the brave new world of private policing. Should private sector justice adhere to constitutional demands imposed on the public sector when detecting criminality or apprehending criminals? Should the Fourth Amendment apply in private sector cases? Are citizens who are arrested and have their persons and property searched and seized by private security personnel entitled to the same protections as individuals apprehended by the public police? Have public and private police essentially merged, or become so entangled as to prompt constitutional protections? Does public policy and constitutional fairness call for an expansive interpretation of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth amendments regarding private security actions? Clarification of these constitutional dilemmas is the prime aim of this chapter.

The ACLU has longed for an application of constitutional principles to private sector justice. See http://acluva.org/4178/aclu-legal-filing-says-private-security-guards-bound-by-constitution-when-detaining-suspects.

Constitutional Framework of American Criminal Justice

Considerable protections are provided against governmental action that violates the Bills of Rights. Most applicable is the Fourth Amendment, which provides:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated and no warrants shall issue upon their probable cause supported by oath, affirmation and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.6

Responding to the clamor for individual rights, calls for a reduction in arbitrary police behavior, and a general recognition that the rights of the individual are sometimes more important than the rights of the whole, judicial reasoning, public opinion, and academic theory for since the early 1990s have suggested and formulated an expansive interpretation of the Fourth Amendment.7 When and where police can be constrained and criminal defendants liberated appears to be the trend.

On its face, and in its express text, the Fourth Amendment is geared toward public functions.8 The concepts of a “warrant,” an “oath,” or “affirmation” are definitions that expressly relate to public officialdom and governmental action. Courts have historically been reticent to extend those protections to private sector activities. In Burdeau v. McDowell, 9 the Supreme Court held unequivocally that Fourth Amendment protection was not available to litigants and claimants arrested, searched, or seized by private parties. The Court explicitly remarked:

The Fourth Amendment gives protection against unlawful searches and seizures…. Its protection applies to governmental actions. Its origin and history clearly shows that it was intended as a restraint upon the activity of sovereign authority and was not intended to be a limitation upon other than governmental agencies.10

The Court’s ruling is certainly not surprising, given the historical tug-of-war between federal and states’ rights in the application of constitutional law. Over the long history of constitutional interpretation, courts have been hesitant to expand constitutional protections to cover the actions of private individuals rather than governmental actions. The Burdeau decision has been continuously upheld in a long sequence of cases and is considered an extremely formidable precedent.11 The Burdeau decision and its progeny enforce the general principle that the Fourth Amendment is applicable only to arrests, searches, and seizures conducted by governmental authorities. The private police and private security system have historically been able to avoid the constrictions placed on the public police in the detection and apprehension of criminals.12

If constitutional protections do not inure to defendants and litigants processed by private sector justice, then what protections do exist? Could it be argued that the line between private and public justice has become indistinguishable or at least so muddled that the roles blur? Are private citizens, subjected to arrest, search, and seizure actions by private police, entitled to some level of criminal due process that is fundamentally fair and not overly intrusive? Does the Fourth Amendment’s strict adherence to the protection of rights solely in the public and governmental realm blindly disregard the reality of public policing? Is this an accurate assessment of what the general citizenry experiences? Or should the constitution be more generously applied to encompass the actions of private police and security operatives? All of these dilemmas are, at first glance, easy to answer, when assessing case law. Even despite the continuous resistance to said applications, the advocates for such arguments are perpetually persistent.

Arrest and Private Sector Justice

As a general proposition, private security officers, private police, and other private enforcement officials may exercise arrest rights at the same level of authority as any private citizen:

While many private security personnel perform functions similar to public law enforcement officers, they generally have no more formal authority than an average citizen. Basically, because the security officer acts on behalf of the person, business, corporation, or other entity that hires him, that entity’s basic right to protect persons and property is transferred to the security officer.13

When one considers the amazing similarity of service and operation between public and private police functions, the general assertion that security officers and other responsible personnel are guided only by the rights of the general citizenry seems extraordinary. Private police serve a multiplicity of purposes, including the protection of property and persons from criminal activity, calamity, and destructive events; the surveillance and investigation of internal and external criminal activity in business and industry; and the general maintenance of public order.14 Therefore, it would seem prudent that private police be guided by some level of constitutional and statutory scrutiny. However, “unless deputized, commissioned, or provided for by ordinance or state statute, private security personnel possess no greater legal powers than any private citizen.”15

For the most part, the lack of express language in guiding constitutional documents that exclusively tend to matters of “state action,” or governmental action, the private agent is left out of the mix. This is the stark reality when reading and interpreting constitutional texts.

Because private police do not derive their authority from a constitutional framework, the foundation for the arrest action rests in the common and statutory law—those codifications that simultaneously give the power of arrest to a private person. “The security officer has the same rights both as a citizen and as an extension of an employee’s right to protect his employer’s property. Similarly, this common law recognition of the right of defense of self and property is the legal underpinning for the right of every citizen to employ the services of others to protect his property against any kind of incursion by others.”16

The Law of Citizen’s Arrest: The Private Security Standard

The scope of permissible citizen’s arrest has remained fairly constant in American jurisprudence. At common law, the private citizenry could make a permissible arrest for the commission of any felony in order to protect the safety of the public.17 An arrest could also be effected for misdemeanors that constituted a breach of the peace or public order, but only when immediate apprehension and a presence of an arresting officer was demonstrated. Much of our contemporary analysis of reasonable suspicion and probable cause also relates to the citizen’s right to subject another individual to the arrest process. “A citizen could perform a valid and lawful arrest on his own authority, if the person arrested committed a misdemeanor in his presence or if there were reasonable grounds to believe that a felony was being or had been committed by the arrestee although not in the presence of the arresting citizen.”18 Private citizens are also permitted to search individuals that they have arrested or detained for safety reasons, and this right is comparable to the incident to arrest or stop and frisk standard applicable in the public jurisdiction. “When an articulable suspicion of danger exists, granting a private policeman or citizen the authority to search for the purpose of finding or seizing weapons of an arrestee is at least equivalent to a pat down approved by Terry v. Ohio, and seems to be a necessary concomitant of the power to arrest.” [Discussing Terry v. Ohio]19

A review of the opinion of the Wisconsin attorney general on the power of private security guards to make arrests is presented at http://www.doj.state.wi.us/ag/opinions/2008_09_03Mohr.pdf.

When compared to public officials’ arrest rights, the private citizen has a heavier burden of demonstrating actual knowledge, presence at the events, or other firsthand experience that justifies the apprehension. These added requirements of citizen’s arrest reflect caution. In some states, a private citizen can arrest under any of the following scenarios:

Statutorily, the scope of citizen’s arrest varies according to jurisdiction. A list of statutory enactments, from Alaska to Florida, can be found in the Appendix 1. Two legislative examples are as follows:

(a) A private person or a peace officer without a warrant may arrest a person

In Illinois, a police officer “can make an extraterritorial warrantless arrest in the same situation that any citizen can make an arrest.”22

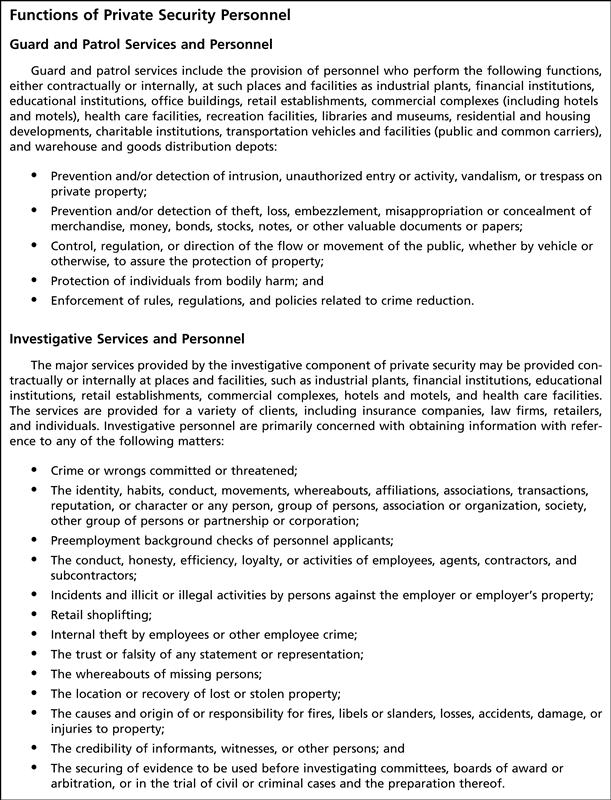

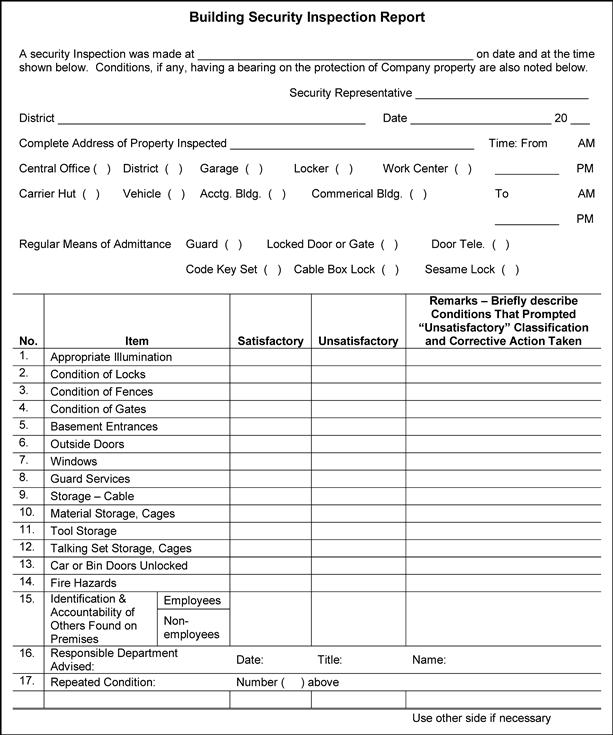

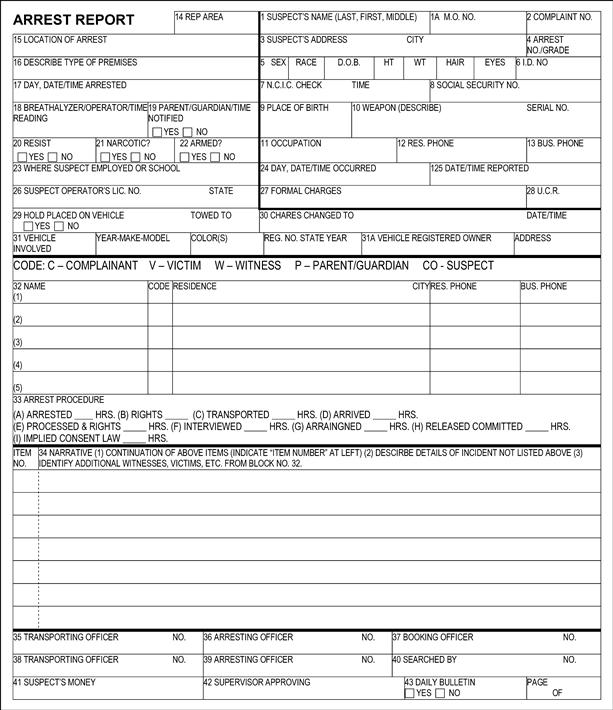

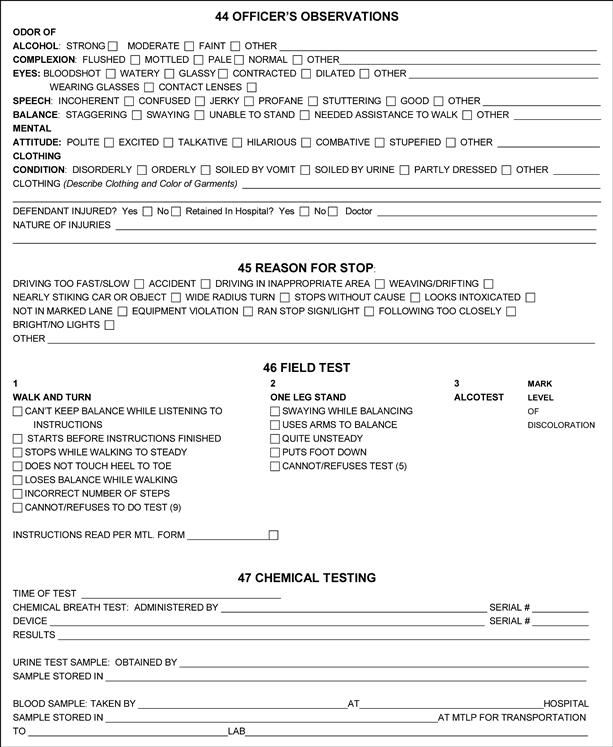

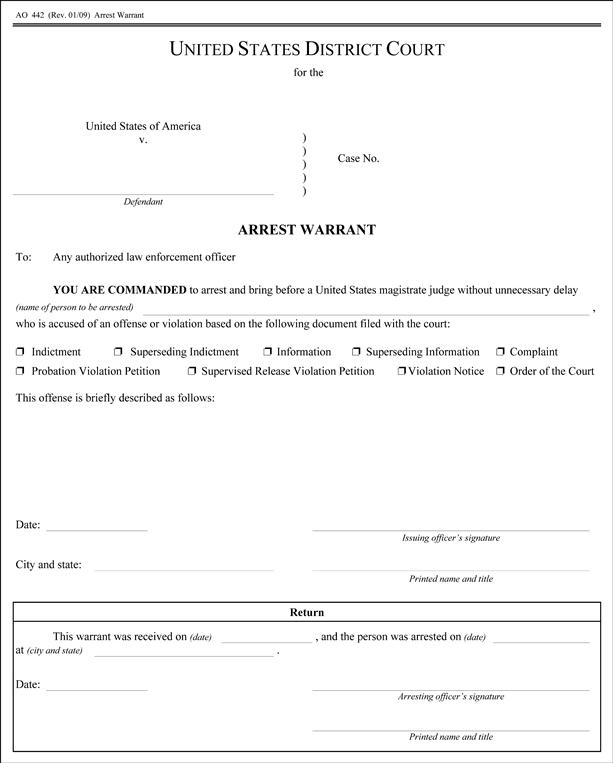

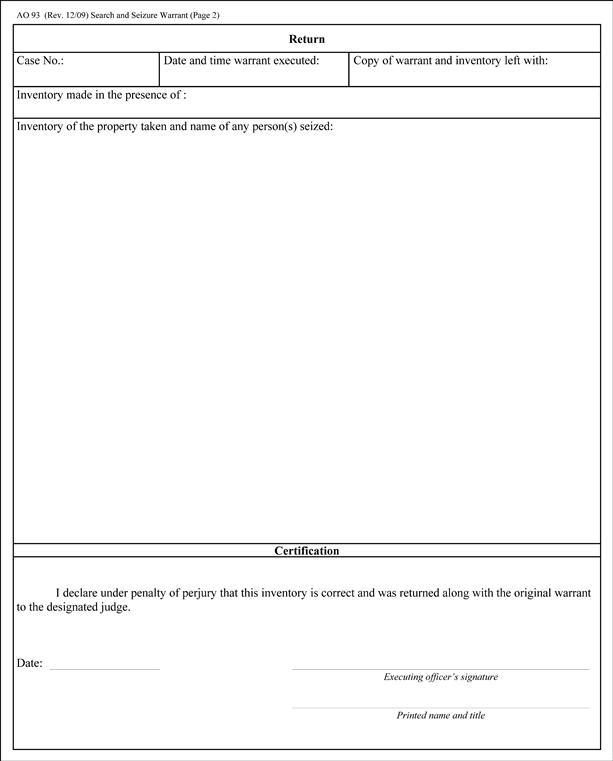

To thwart and effectively defend against citizen-based challenges to the regularity of the citizen arrest, the security officer conducting any arrest should complete documentation that justifies the decision making. First, an incident report, which details the events comprising the criminal conduct, should be completed (Figure 3.1).23 Second, an arrest report (Figure 3.2)24 records the officer’s actions. An arrest warrant is shown in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.1 Building Security Inspection Report.

Figure 3.2 Arrest Report.

Figure 3.3 U.S. District Court Arrest Warrant.

Generally, legislation concerning citizen’s arrest needs to attend to diverse variables and criteria, which determine its legality. Types and category of crimes, standards of action, time of day, and alternative retreat potential are but a few of these. Critics have charged that the codification appears to be “more a product of legislation in discrimination than a logical adaptation of a common law principle to the conditions of modern society.”25 While legislators hope and wish for skilled, trained, and educated individuals to effect as many arrests as possible, the statutes have essentially sought a middle ground permitting arrests only when needed and emphasizing the system of citizen referral to public authority when at all possible. However, the process of citizen’s arrest is “filled with legal pitfalls,” which “may depend on a number of legal distinctions, such as the nature of the crime being committed and proof of actual presence at the time and place of the incident.”26 Some analyses of these variables and factors follow.

Time of the Arrest

Both common law and statutory rationales for the privilege or right of citizen’s arrest impose time restrictions on the arresting party. In the case of felonies, the felon’s continuous evasion of authorities was considered a substantial and continuing threat against the public order and police. Therefore, an arresting party could complete the process regarding a felon at any time. Persons committing misdemeanors, however, were afforded greater protection from private citizen arrest actions. Some states require that the person committing a misdemeanor be arrested by a private citizen only when actually engaging in conduct that undermines the public order. However, other states have dramatically expanded the misdemeanor defense category beyond the breach of the public peace typology. More specifically, states have expanded the arrest power to include petty larceny and shoplifting,27 and they have provided a rational barometer of when citizens’ arrests are appropriate.

Also relevant to time limitation analysis is “freshness” of the pursuit. A delay or deferral of the arrest process will result in a loss of the arrest privilege. Predictably, freshness in the pursuit may be difficult to measure in precise terms. Timing restrictions “serve to compel reliance on police once the danger of immediate public harm from criminal activity has ceased.”28

Presence and Commission

Presence during commission of the offense is a clear requirement in a case involving misdemeanors where firsthand, actual knowledge corroborates the arresting party’s decision making. “The purpose of the requirement is presumably to prevent the danger and imposition involved in mistaken arrests based upon uncorroborated or second hand information. Its principal impact is in cases where the citizen learns the commission of a crime and assumes the responsibility of preventing the escape of an offender.”29 If firsthand observation is called for, the arrest is properly based on an eyewitness view. In other cases, especially the full range of felonies, a citizen can arrest another person based on the standard of reasonable grounds, a close companion to the probable cause test. To find probable cause, one must demonstrate that someone has committed, is likely committing, or is about to commit a crime. Being present during an offense plainly meets this standard. But numerous other cases are just as probative despite a lack of immediate presence. Critics have charged that requiring presence as a basis for the privilege to arrest is nonsensical. A note in the Columbia Law Review gives an example by analogy:

It is here that the requirement produces incongruous results. If a citizen hears a scream and turns around to see a bleeding victim on the ground and a fleeing figure, he can arrest the assailant with impunity. Yet if he comes upon the scene but a moment later under identical circumstances, his apprehension of the fugitive would be illegal.30

A few jurisdictions have attempted to reconcile this dilemma by allowing felony arrests to occur without a presence requirement. Presence is simply replaced with a reasonable grounds or reasonable cause criteria. The Report of the Task Force on Private Security from the National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals addresses this qualification:

Under the statutes that authorize an arrest based on “reasonable cause” or “reasonable grounds” it has been held in most jurisdictions that these terms generally mean sufficient cause to warrant suspicion in the arrester’s mind at the time of the arrest. Some jurisdictions have expanded the rule of suspicion to require a higher standard; yet, there are no uniform criteria emerging from the numerous decisions on the questions.31

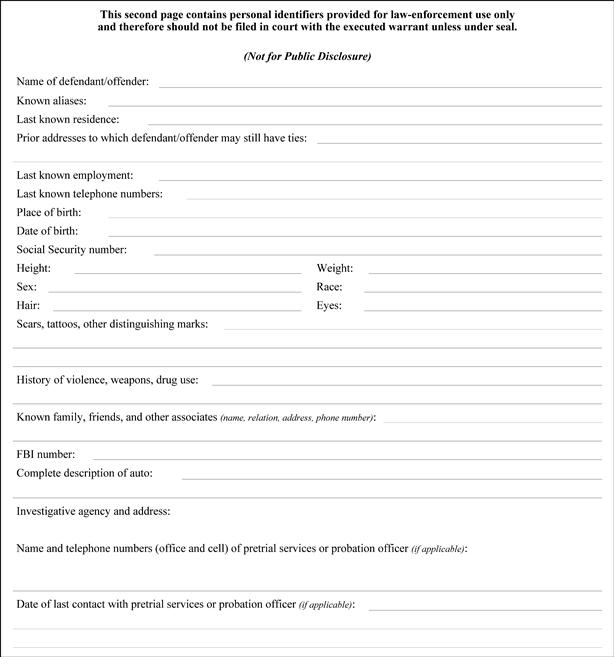

A review of citizen’s arrest standards on a state-by-state basis is provided in Table 3.1. Note that Table 3.1 makes a distinction between minor and major offenses, namely between felonies and misdemeanors. It also outlines the general grounds leading to a finding of probable or reasonable grounds required to affect an arrest. Some general statutory conclusions can be made:

3. Presence is generally required in all minor offenses commonly known as misdemeanors.

4. Presence is required in a minority of jurisdictions in felony cases.

Table 3.1. Summary of Citizen’s Arrest Standards by State

|

In sum, hunches, guesses, or general surmises are not a satisfactory framework in which to conduct citizens’ arrests. Just as the public police system must adhere to some fundamental standards of fairness regarding the arrest, search, and seizure process, so too must private sector justice. Arrest based on reasonable grounds is the benchmark.

The Restatement of the Law of Torts cogently justifies a citizen’s arrest in these circumstances:

a. If the other person has committed a felony for which he is arrested;

b. If a felony has been committed and the arrestor reasonably suspects the arrestee has committed it;

d. If the arrestee has attempted to commit a felony in the arrestor’s presence and the arrest is made at once or in fresh pursuit.32

Depending on jurisdiction, another factor to be considered by security personnel in the arrest process is notice, an announcement advising a suspect of one’s intention to arrest. The level of force utilized and the detention techniques for a person awaiting formal processing may also be significant factors in any resolution of the propriety of a citizen’s arrest.

The Law of Search and Seizure: Public Police

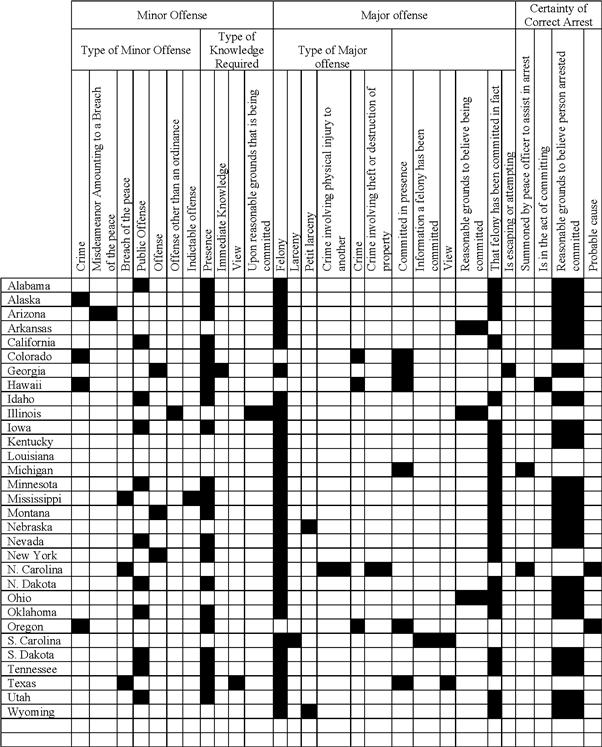

There are two fundamental ways in which a public peace officer can conduct a search and seizure: with or without a warrant. Warrants are expressly referenced in the Fourth Amendment and their probable cause determination is explicitly mentioned. Searches with warrants are mandated unless one of the various exceptional circumstances exists to justify a warrantless action. There are numerous exceptions to the warrant requirement from consent of the arrested party to exigency and safety. The exceptions have been shaped and crafted, not as an affront to the fundamental protection, but in full recognition of the practical reality and criminal activity and law enforcement policy. When public police search without justification or legal right, the evidence so taken is excluded due to the constitutional infringement. This restrictive policy is labeled the exclusionary rule.33 In Mapp v. Ohio 34 the U.S. Supreme Court rendered inadmissible evidence obtained by public law enforcement officials in violation of the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth amendments of the U.S. Constitution. The Fourteenth Amendment has selectively incorporated these three amendments as they apply to state police action. For an example of a federal search warrant see Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 U.S. District Court, Search & Seizure Warrant.

As part of routine procedure, a police officer who makes a lawful and valid arrest, with or without an arrest warrant or at arm’s length, is entitled to search the suspect and the area within his immediate control. At other times, the search and eventual seizure may arise from a plain view observation. Plain view permits any law enforcement official who sees contraband, weaponry, or other evidence of criminality within direct sight or observation to seize the evidence without warrants or other legal requirements. Police may search and seize contraband in any open space environment, such as agricultural centers for narcotics. This warrantless exception is often referred to as the open field rule.35 Police can search and seize evidence in any abandoned property or place. Warrant requirements for police are waived in cases of extreme emergency known as exigent situations, as when there is a high likelihood of lost evidence. Naturally, police have also been given leeway to conduct warrantless searches when their personal safety is at risk. Auto searches and consent searches generally bypass the more restrictive warrant requirements. Stop and frisk, as outlined in Terry v. Ohio, 36 allows police to “pat down” a suspect if it’s reasonable to suspect weaponry or other potential harm.37

A review the Handout summary prepared by Stanford University on the Terry doctrine and its inapplicability to private security guards can be found at http://streetlaw.stanford.edu/Curriculum/Short_Lesson3.pdf.

One other factor is worth mentioning as well—namely, immunity. Historically, public officers operated under some level of “immunity,” whether whole or qualified in design. That immunity insulated government agents from liability as long as his or her “actions [are] taken in good faith pursuant to their discretionary authority.”38 Determining whether a public official is entitled to qualified immunity, then, “requires a two-part inquiry: (1) Was the law governing the state official’s conduct clearly established? (2) Under that law could a reasonable state official have believed his conduct was lawful?”39 This standard “gives ample room for mistaken judgments by protecting ‘all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.’”40, 41

The Law of Search and Seizure: Private Police

The rationale behind the exclusionary rule is to deter police misconduct and to halt illegal and unjustified investigative processes. As noted previously, in Burdeau v. McDowell, 42 the Supreme Court of the United States was unwilling to extend the exclusionary rule to private sector searches. Burdeau held exclusionary rule inapplicable, as it was clear that there was “no invasion of the security afforded by the Fourth Amendment against unreasonable search and seizure as whatever wrong was done by the act of individuals in taking the property of another.”43 Trial attorney John Wesley Hall, Jr., writes in Inapplicability of the Fourth Amendment:

One of the oldest principles in the law of search and seizure holds that searches by private or non-law enforcement personnel are not protected by the Fourth Amendment regardless of the unlawful manner in which the search may have been conducted. The Fourth Amendment historically only applies to direct governmental action and not the passive act of using relevant evidence obtained by a private party’s conduct.44

Others disagree with these lines of legal explanation, especially when one considers how extensive the inroads of private sector justice are in the war on crime. The regularity of arrest, search, and seizure processes in private security settings are now amply documented. In retail establishments, security personnel regularly search individuals suspected of shoplifting. Security firms have now taken over entire neighborhoods, housing projects and planned communities, and even cities and towns.

Searches are also seen in business and industrial applications. “These could include search of a car or dwelling for pilfered goods or the use of electronic surveillance devices to obtain information for use in making legal, business or personal decisions.”45 Additionally, surveillance by private security companies utilizing various forms of electronic eavesdropping, emerging technologies, and other interception devices, while still regulated to some extent in the public sector, is more readily utilized and commonly employed in the private sector.

The Private Security Advisory Council ponders a noticeable lack of either common law or statutory authority governing private search parameters.46 Yet even with the industry’s practices, this lack of restrictions in the private sector is inexcusable. However, the council does list these instances as legitimate private search actions:

In some respects, these four categories parallel the very conditions under which public law enforcement may permissibly conduct warrantless searches. “As a general consideration since the public police are intended to be society’s primary law enforcers, the limitations on public police search should set the upper boundaries of allowable search by private police.”48 Of course, it is also critical to note that while constitutional restrictions may not yet apply in the private security realm without a more demonstrable showing, other remedies are available to those who have been illegally arrested, searched, or had personal effects or property unjustly seized. These tort actions and corresponding civil and criminal remedies include, but are not limited to the following:

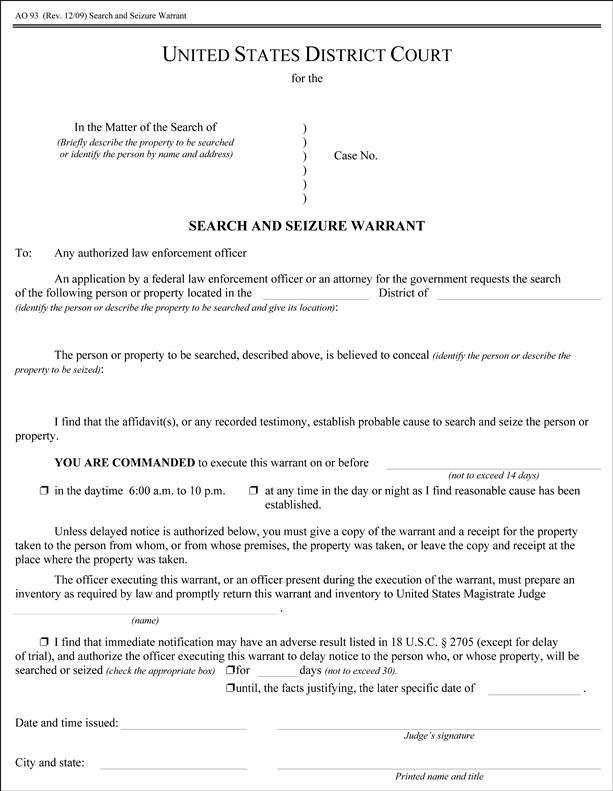

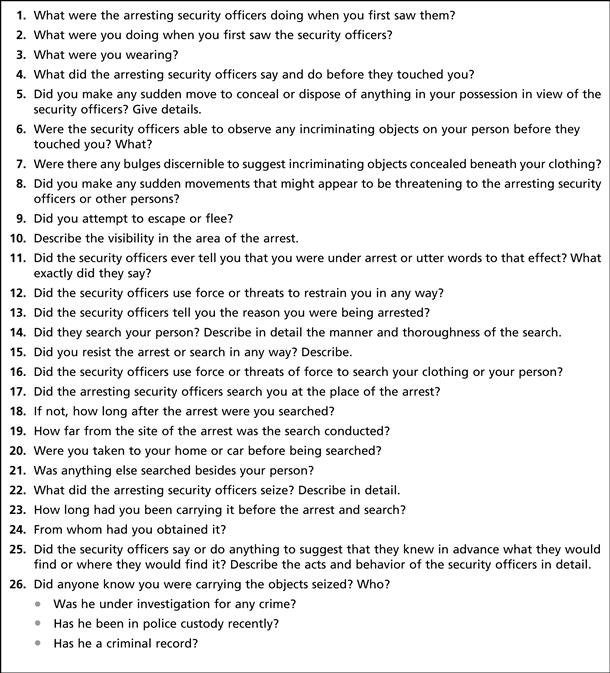

To track a private sector search of the person, review the checklist at Figure 3.5.49

Figure 3.5 Checklist for Search and Seizure.

In summary, the constitutional guidelines and case law interpreting standards of public police practice have yet to make a remarkable dent in private security activity. Relying on strong precedent, statutory noninvolvement, and a general hesitancy on the part of the courts and the legislatures to expand constitutional doctrines like the exclusionary rule, private security practitioners are still provided a safe haven in the law of arrest, search, and seizure.

Challenges to the Safe Harbor of Private Security

Despite this general resistance to expanding the constitutional dynamic to private sector police, legal advocates push hard for such reforms, and a variety and steady stream of case law reach appellate courts across the country every year. Some case law is more significant than others. Few cases have had much success in altering this legal landscape. An appeals decision from California carved out a noticeable precedent for those arguing for the expansion of these constitutional rights.

In People v. Zelinski, 50 the California Supreme Court ruled that security officers were thoroughly empowered to institute a search to recover goods that were in plain view, but that any intrusion into the defendant’s person or effects was not authorized as incident to a citizen’s arrest or protected under the Merchant’s Privilege Statute. The court concluded that the evidence seized was “obtained by unlawful search and that the constitutional prohibition against unreasonable search and seizure affords protection against the unlawful intrusive conduct of these private security personnel.”51