THE JURY

THE JURY11

11.1 INTRODUCTION

It is generally accepted that the jury of ‘12 good men and true’ lies at the heart of the British legal system. The implicit assumption is that the presence of 12 ordinary lay-persons, randomly introduced into the trial procedure to be the arbiters of the facts of the case, strengthens the legitimacy of the legal system. It supposedly achieves this end by introducing a democratic humanising element into the abstract impersonal trial process, thereby reducing the exclusive power of the legal professionals who would otherwise command the legal stage and control the legal procedure without reference to the opinion of the lay majority.

According to EP Thompson:

The English common law rests upon a bargain between the law and the people. The jury box is where the people come into the court; the judge watches them and the jury watches back. A jury is the place where the bargain is struck. A jury attends in judgement not only upon the accused but also upon the justice and humanity of the law [Writing by Candlelight].

Few people have taken this traditional view to task but, in a thought-provoking article in the Criminal Law Review ([1991] Crim LR 740), Penny Darbyshire did just that. In her view, the jury system has attracted the most praise and the least theoretical analysis of any component of the criminal justice system. As she correctly pointed out, and as will be shown below, juries are far from being either a random or a representative section of the general population. In fact, Darbyshire goes so far as to characterise the jury as ‘an anti-democratic, irrational and haphazard legislator, whose erratic and secret decisions run counter to the rule of law’. She concedes that while the twentieth century lay justices are not representative of the community as a whole, neither is the jury. She points out that jury equity, by which is meant the way in which the jury ignores the law in pursuit of justice, is a double-edged sword which may also convict the innocent; and counters examples such as the Clive Ponting case with the series of miscarriages of justice relating to suspected terrorists in which juries were also involved.

Darbyshire is certainly correct in taking to task those who would simply endorse the jury system in an unthinking, purely emotional manner. With equal justification, she criticises those academic writers who focus attention on the mystery of the jury to the exclusion of the hard reality of the magistrates’ court. It is arguable, however, that she goes to the other extreme. Underlying her analysis and conclusions is the idea that ‘the jury trial is primarily ideological’ and that ‘its symbolic significance is magnified beyond its practical significance by the media, as well as academics, thus unwittingly misleading the public’. While one might not wish to contradict the suggestion that the jury system operates as a very powerful ideological symbol, supposedly grounding the criminal legal system within a framework of participative democracy and justifying it on that basis, it is simply inadequate to reject the practical operation of the procedure on that basis alone. Ideologies do not exist purely in the realm of ideas, they have real, concrete manifestations and effects; in relation to the jury system, those manifestations operate in such a way as to offer at least a vestige of protection to defendants. In regard to the comparison between juries and the summary procedure of the magistrates’ courts, Darbyshire puts two related questions. First, she asks whether the jury system is more likely to do justice and get the verdict right than the magistrates’ courts; then she goes on to ask why the majority of defendants are processed through the magistrates’ courts. These questions are highly pertinent; it is doubtful, however, whether her response to them is equally pertinent. Her answers would likely be that the jury does not perform any better than the magistrates and, therefore, it is immaterial that the magistrates deal with the bulk of cases. Her whole approach would seem to be concentrated on denigrating the performance of the jury system. A not untypical passage from her article admits that, in relation to the suspect terrorist miscarriages of justice, juries ‘were not to blame for these wrongful convictions’. However, she then goes on in the same sentence to accuse the juries of failing ‘to remedy the lack of due process at the pre-trial stage’, and thus blames them for not providing ‘the brake on oppressive State activity claimed for the jury by its defenders’.

Although there is most certainly scope for a less romantic view of how the jury system actually operates in practice, Darbyshire’s argument seems to be that the magistrates are not very good but then neither are the juries; and as they only operate in a small minority of cases anyway, the implication would seem to be that their loss would be no great disadvantage. Others, however, would maintain that the jury system does achieve concrete benefits in particular circumstances and would argue further that these benefits should not be readily given up. Among the latter is Michael Mansfield QC who, in an article in response to the Runciman Report, claimed that the jury ‘is the most democratic element of our judicial system’ and the one that ‘poses the biggest threat to the authorities’. (These questions will be considered further in relation to the Report of the Runciman Commission and the Criminal Justice (Mode of Trial) Bills, at 11.7.1 below.)

Having defended the institution of the jury generally, it has to be recognised that there are particular instances that tend to bring the jury system into disrepute. For example, in October 1994, the Court of Appeal ordered the retrial of a man convicted of double murder on the grounds that four of the jurors had attempted to contact the alleged victims using a Ouija board in what was described as a ‘drunken experiment’ (R v Young (1995)). A second convicted murderer appealed against his conviction on the grounds of irregularities in the manner in which the jury performed its functions. Among the allegations levelled at the jury was the claim that they clubbed together and spent £150 on drink when they were sent to a hotel after failing to reach a verdict. It was alleged that some of the jurors discussed the case against the express instructions of the judge and that on the following day, the jury foreman had to be replaced because she was too hung-over to act. One female juror was alleged to have ended up in bed with another hotel guest.

A truly remarkable case came to light in December 2000 when a trial, which had been going on for 10 weeks, was stopped on the grounds that a female juror was conducting what were referred to as ‘improper relations’ with a male member of the jury protection force who had been allocated to look after the jury during the trial. The relationship had become apparent after the other members of the jury had found out that they were using their mobile phones to send text messages to one another during breaks in the trial. That aborted trial was estimated to have cost £1.5 million, but it emerged that this was the second time the case had to be stopped on account of inappropriate behaviour on the part of jury members. The first trial had been abandoned after some of the jury were found playing cards when they should have been deliberating on the case.

Another example of the possible criticisms to be levelled against the misuse of juries occurred in Stoke-on-Trent, where the son of a court usher and another six individuals were found to have served on a number of criminal trial juries. While one could praise the public spirited nature of this dedication to the justice process, especially given the difficulty in getting members of jury panels, it might be more appropriate to condemn the possibility of the emergence of a professional juror system connected to court officials. Certainly, the Court of Appeal was less than happy with the situation, and overturned a conviction when the Stoke practice was revealed to it.

Over the past 15 years, the operation of the jury system has been subject to one Royal Commission (Runciman), one review (Auld) and several statutory attempts to alter it. An examination of these various endeavours will be postponed until the end of this chapter; for the moment, attention will be focused on the jury system as it currently functions.

11.2 THE ROLE OF THE JURY

It is generally accepted that the function of the jury is to decide on matters of fact, and that matters of law are the province of the judge. Such may be the ideal case, but most of the time, the jury’s decision is based on a consideration of a mixture of fact and law. The jurors determine whether a person is guilty on the basis of their understanding of the law as explained to them by the judge.

The oath taken by each juror states that they ‘will faithfully try the defendant and give a true verdict according to the evidence’, and it is contempt of court for a juror subsequent to being sworn in to refuse to come to a decision. In 1997, Judge Anura Cooray sentenced two women jurors to 30 days in prison for contempt of court for their failure to deliver a verdict. One of the women, who had been the jury foreman, claimed that the case, involving an allegation of fraud, had been too complicated to understand, and the other had claimed that she could not ethically judge anyone. Judge Cooray was quoted (The Guardian, 26th March 1997) as justifying his decision to imprison them on the grounds that:

I had to order a re-trial at very great expense. Jurors must recognise that they have a responsibility to fulfil their duties in accordance with their oath.

The women only spent one night in jail before the uproar caused by Cooray’s action led to their release and the subsequent overturning of his sentence on them.

It should be appreciated that serving on a jury can be an extremely harrowing experience. Jurors are the arbiters of fact, but the facts they have to contend with can be horrific. Criticisms have been levelled at the way in which the jury system can subject people to what in other contexts would be pornography, of either a sexual or violent kind, and yet offer them no counselling when their jury service comes to an end. Many jurors fear reprisals from defendants and their associates. In April 2003, two illegal immigrants, Baghdad Meziane and Brahim Benmerzouga, were convicted of various offences under the Terrorism Act 2000. It appears that they had raised hundreds of thousands of pounds for Al Qa’ida and other radical Islamic organisations. The trial at Leicester Crown Court became a ‘drama unprecedented in legal history’ (S Bird, ‘Jurors too scared to take on case’, The Times, 2 April 2003):

The case began in February, amid extraordinary security arrangements. A jury was sworn in and retired overnight … The next morning one frightened female juror had worked herself up into such a state that she vomited in the jury room. Two others burst into tears … The jury was dismissed – as was a second after a male juror expressed fears for his family’s safety.

The third jury was down to nine members when it was time to deliver a verdict, which it duly did: a verdict of guilty, the accused receiving sentences of 11 years.

Jurors receive inadequate protection and support. The only recognition currently available is that the judge can exempt them from further jury service for a particular period. Many would argue that such limited recognition of the damage that jurors might sustain in performing their civic duty is simply inadequate. Jury service can make excessive (many would say unreasonable) demands on jurors. In May 2005 a fraud trial collapsed after jurors had spent almost two years at the Old Bailey in London (see further, at 11.6.2.2).

11.3 THE JURY’S FUNCTION IN TRIALS

Judges have the power to direct juries to acquit the accused where there is insufficient evidence to convict them, and this is the main safeguard against juries finding defendants guilty in spite of either the absence, or the insufficiency, of the evidence. There is, however, no corresponding judicial power to instruct juries to convict (DPP v Stonehouse (1978); R v Wang (2005)). That being said, there is nothing to prevent the judge summing up in such a way as to make it evident to the jury that there is only one decision that can reasonably be made, and that it would be perverse to reach any other verdict but guilty.

What judges must not do is overtly put pressure on juries to reach guilty verdicts. Finding of any such pressure will result in the overturning of any conviction so obtained. The classic example of such a case is R v McKenna (1960), in which the judge told the jurors, after they had spent all of two and a quarter hours deliberating on the issue, that if they did not come up with a verdict in the following 10 minutes, they would be locked up for the night. Not surprisingly, the jury returned a verdict; unfortunately for the defendant, it was a guilty verdict; even more unfortunately for the judicial process, the conviction had to be quashed on appeal for clear interference with the jury.

In the words of Cassels J:

It is a cardinal principle of our criminal law that in considering their verdict, concerning, as it does, the liberty of the subject, a jury shall deliberate in complete freedom, uninfluenced by any promise, unintimidated by any threat. They stand between the Crown and the subject, and they are still one of the main defences of personal liberty. To say to such a tribunal in the course of its deliberations that it must reach a conclusion … is a disservice to the cause of justice … [R v McKenna [1960] 1 All ER 326 at 329].

Judges do have the right, and indeed the duty, to advise the jury as to the proper understanding and application of the law that it is considering. Even when the jury is considering its verdict, it may seek the advice of the judge. The essential point, however, is that any such response on the part of the judge must be given in open court, so as to obviate any allegation of misconduct (R v Townsend (1982)).

In R v Arshid Khan (2008) Khan appealed against convictions on the ground that the judge at his trial had permitted new evidence to be put to the jury after it had retired to consider its verdict. The situation arose as a result of the jury returning to the court to ask for clarification of evidence relating to mobile phone calls. After the judge had answered the jury’s questions one of Khan’s lawyers made further investigations which revealed that the evidence presented to the jury was inaccurate. The judge was informed of this fact and the jury was re-assembled within two hours of it having been given the information in answer to its questions.

The judge then informed the jury that some of the information may not have been correct. The jury were then told to go home, and to return the following morning to resume their deliberations.

Further investigations revealed that the evidence presented to the jury was in fact inaccurate. On the following morning Khan’s lawyers discussed the results of the investigation with him. And on the understanding that the new evidence might strengthen his case, he agreed that it should be put before the jury. Nonetheless, the jury returned guilty verdicts in relation to the charges against Khan, who subsequently appealed on the ground that the judge had erred in law in permitting the additional evidence to be put before the jury after it had retired.

In rejecting the appeal the Court of Appeal found that there was no reason in principle why the judge should not have agreed to allow the new evidence to be put before the jury. On the contrary, as they stated:

we can see every reason why he should have allowed this evidence to go before the jury. The defence invited the judge to do so on the basis that the evidence assisted the appellant’s case. It was evidence which trial counsel believed was capable of supporting the appellant’s case in an area which both counsel felt the appellant’s evidence was weak and required some support. We have no doubt that the appellant agreed to this course of action.

On that basis the court rejected Khan’s appeal.

The decision in Khan reflects the changed approach of the courts to such situations as historically the authorities support the view that there was an absolute principle that no further evidence should be given after the judge’s summing-up has been concluded and the jury has retired. Thus in R v Owen (1952) in which the trial judge allowed a doctor who had already given evidence in the case to be recalled to give evidence in answer to a question raised by the jury after their retirement, the subsequent conviction was quashed. The reason stated by Lord Goddard CJ was that: ‘once the summing up is concluded, no further evidence ought to be given. The jury can be instructed in reply to any question they may put on any matter on which evidence has been given, but no further evidence should be allowed’.

However, subsequently, in R v Sanderson (1953), the Court of Criminal Appeal, including Lord Goddard CJ, held that it was permissible for the evidence of a witness for the defence to be taken after the summing up had been completed, but before the jury had retired and the ‘very strict rule’ that no evidence whatever must be introduced after the jury had retired was reiterated by Lord Parker CJ in R v Gearing (1968).

However, the introduction of the proviso under s 2(1) of the Criminal Appeal Act 1968 (see 6.5.2 above) led to a change in approach and in R v Davis (1976), the absolute nature of the rule was questioned and such an approach was approved of in R v Karakaya (2005).

More recently in R v Hallam (2007) the Court of Appeal actually held that a verdict was unsafe because a judge had refused to permit the jury to see a photograph which could potentially have assisted the appellant’s defence, but which had come to light only after the summing-up. In that case the court defined the principle as follows:

It used to be understood that there was a very firm rule that evidence cannot be admitted after the retirement of the jury, but more recent authorities confirm that there is no absolute rule to that effect. The question is what justice requires.

In criminal cases, even perversity of decision does not provide grounds for appeal against acquittal. There have been occasions where juries have been subjected to the invective of a judge when they have delivered a verdict with which he disagreed. Nonetheless, the fact is that juries collectively, and individual jurors, do not have to justify, explain or even give reasons for their decisions. Indeed, under s 8 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981, it would be a contempt of court to try to elicit such information from a jury member in either a criminal or a civil law case.

In Attorney General v Associated Newspapers (1994), the House of Lords held that it was contempt of court for a newspaper to publish disclosures by jurors of what took place in the jury room while they were considering their verdict, unless the publication amounted to no more than a re-publication of facts already known. It was decided that the word ‘disclose’ in s 8(1) applied not just to jurors, but to any others who published their revelations.

In an interview for The Times in January 2001, the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Woolf, expressed himself very strongly in favour of lifting the ban on jury research, though he emphasised that great care was needed in the conduct of any such research. Fresh impetus may be given to this proposal by the concerns about juries engendered by the decision of the Court of Appeal in Grobbelaar v News Group Newspapers (see below).

These factors place juries in a very strong position to take decisions that are ‘unjustifiable’ in accordance with the law, for the simple reason that they do not have to justify the decisions. Thus, juries have been able to deliver what can only be described as perverse decisions. In R v Clive Ponting (1985), the judge made clear beyond doubt that the defendant was guilty, under the Official Secrets Act 1911, of the offence with which he was charged: the jury still returned a not guilty verdict. Similarly, in the case of Pat Pottle and Michael Randall, who had openly admitted their part in the escape of the spy George Blake, the jury reached a not guilty verdict in open defiance of the law.

In R v Kronlid (1996), three protestors were charged with committing criminal damage, and another was charged with conspiracy to cause criminal damage, in relation to an attack on Hawk Jet aeroplanes that were about to be sent to Indonesia. The damage to the planes allegedly amounted to £1.5 million and they did not deny their responsibility for it. They rested their defence on the fact that the planes were to be delivered to the Indonesian State, to be used in its allegedly genocidal campaign against the people of East Timor. On those grounds, they claimed that they were in fact acting to prevent the crime of genocide. The prosecution cited assurances, given by the Indonesian government, that the planes would not be used against the East Timorese, and pointed out that the UK government had granted an export licence for the planes. As the protestors did not deny what they had done, it was apparently a mere matter of course that they would be convicted as charged. The jury, however, decided that all four of the accused were innocent of the charges laid against them. A government Treasury minister, Michael Jack, subsequently stated his disbelief at the verdict of the jury. As he stated:

I, and I am sure many others, find this jury’s decision difficult to understand. It would appear there is little question about who did this 25damage. For whatever reason that damage was done, it was just plain wrong [(1996) The Independent, 1 August].

As stated above, jurors swear to return ‘a true verdict according to the evidence’. Such verdicts may be politically inconvenient.

It is perhaps just such a lack of understanding, together with the desire to save money on the operation of the legal system, that has motivated the government’s expressed wish to replace jury trials in relation to either way offences (see below, at 11.8). In any event, juries continue to reach perverse decisions where they are sympathetic to the causes pursued by the defendants. Thus, in September 2000, 28 Greenpeace volunteers, including its executive director Lord Melchett, were found not guilty of criminal damage after they had destroyed a field containing genetically modified maize. They had been found not guilty of theft in their original trial in April of that year. Judge David Mellor told the jury:

It is not about whether GM crops are a good thing for the environment or a bad thing. It is for you to listen to the evidence and reach honest conclusions as to the facts.

However, the jury seemed to have adopted a different approach.

Fear of not achieving a successful conviction also appears to be the reason behind the CPS’s belated decision, in February 2004, not to pursue the prosecution of Katherine Gun. Gun was the former GCHQ translator who revealed that the UK and the USA were involved in spying on members of the United Nations before a crucial vote on whether the 2003 war on Iraq would be sanctioned by the UN. Although she admitted she was the source of the leak and was consequently, at least prima facie, in breach of the Official Secrets Act, her prosecution was dropped after she had put forward the defence of necessity. The decision was apparently taken on the guidance of the Attorney General who was involved in the Iraq question from the beginning, being the source of the government’s advice that the war was legal without the need for a specific resolution to that effect by the United Nations. In September 2008 six Greenpeace climate change activists were cleared of causing £30,000 of criminal damage at a coal-fired power station in Kent. They had admitted trying to shut down the station by occupying the smokestack and painting the word ‘Gordon’ down the chimney. However, the jury found them not guilty on the basis of their defence, which was that they were justified in their action as they were acting to prevent climate change causing greater damage to property around the world. In his summing-up at the end of an eight-day trial, the judge, David Caddick, said the case centred on whether or not the protesters had a lawful excuse for their actions and the jury found that they did.

A non-political example of this type of case can be seen in the jury’s refusal to find Stephen Owen guilty of any offence after he had discharged a shotgun at the driver of a lorry that had killed his child. And, in September 2000, a jury in Carlisle found Lezley Gibson not guilty on a charge of possession of cannabis after she told the court that she needed it to relieve the symptoms of the multiple sclerosis from which she suffered. The tendency of the jury occasionally to ignore legal formality in favour of substantive justice is one of the major points in favour of its retention, according to its proponents.

11.3.1 APPEALS FROM DECISIONS OF THE JURY

In criminal law, it is an absolute rule that there can be no appeal against a jury’s decision to acquit a person of the charges laid against him. Although there is no appeal as such against acquittal, there does exist the possibility of the Attorney General referring the case to the Court of Appeal, to seek its advice on points of law raised in criminal cases in which the defendant has been acquitted. This procedure was provided for under s 36 of the CJA 1972, although it is not commonly resorted to. It must be stressed that there is no possibility of the actual case being reheard or the acquittal decision being reversed, but the procedure can highlight mistakes in law made in the course of Crown Court trial and permits the Court of Appeal to remedy the defect for the future. (See Attorney General’s Reference (No 1 of 1988) (1988) for an example of this procedure, in the area of insider dealing in relation to shares on the Stock Exchange. This case is also interesting in relation to statutory interpretation. See also Attorney General’s Reference (No 3 of 1999), considered above, at 9.3.2.)

In civil law cases, the possibility of the jury’s verdict being overturned on appeal does exist, but only in circumstances where the original verdict was perverse, that is, no reasonable jury properly directed could have made such a decision.

11.3.2 MAJORITY VERDICTS

The possibility of a jury deciding a case on the basis of a majority decision was introduced by the CJA 1967. Prior to this, the requirement was that jury decisions had to be unanimous. Such decisions are acceptable where there are:

• not less than 11 jurors and 10 of them agree; or

• there are 10 jurors and nine of them agree.

Where a jury has reached a guilty verdict on the basis of a majority decision, s 17(3) of the Juries Act (JA) 1974 requires the foreman of the jury to state in open court the number of jurors who agreed and the number who disagreed with the verdict. See R v Barry (1975), where failure to declare the details of the voting split resulted in the conviction of the defendant being overturned. In R v Pigg (1983), the House of Lords held that it was unnecessary to state the number who voted against where the foreman stated the number in favour of the verdict, and thus the determination of the minority was a matter of simple arithmetic.

However, in R v Mendy (1992), when the clerk of the court asked the foreman of the jury how a guilty decision had been reached, he replied that it was ‘by the majority of us all’. The ambiguity of the reply is obvious when it is taken out of context and this was relied on in a successful appeal. It was simply not clear whether it referred to a unanimous verdict, as the court at first instance had understood it, or whether it referred to a real majority vote, in which case it failed to comply with the requirement of s 17(3) as applied in R v Barry. The Court of Appeal held that in such a situation, the defendant had to be given the benefit of any doubt and he was discharged.

The Court of Appeal adopted a different approach in R v Millward (1999). The appellant had been convicted, at Stoke-on-Trent Crown Court, of causing grievous bodily harm. Although the jury actually had reached a majority decision, the foreman in response to the questioning of the clerk of the court mistakenly stated that it was the verdict of them all. The following day, the foreman informed the judge that the verdict had in fact been a majority verdict of 10 for guilty and two against.

The Court of Appeal met the subsequent challenge with the following exercise in sophisticated reasoning. The court at first instance had apparently accepted a unanimous verdict. Therefore, s 17 had not been brought into play at all. And, bearing in mind s 8 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981, discouraging the disclosure of votes cast by jurors in the course of their deliberations, the issue had to be viewed under the policy of the law. It would set a very dangerous precedent if an apparently unanimous verdict of a jury delivered in open court, and not then challenged by any juror, was reopened and subjected to scrutiny. It would be difficult to see how the court could properly investigate a disagreement as to whether jurors had dissented or not. In the instant case, there was a proper majority direction and proper questions asked of the jury and apparently proper and unambiguous answers given without challenge. Therefore, there should be no further inquiry.

There is no requirement for the details of the voting to be declared in a majority decision of not guilty.

11.3.3 DISCHARGE OF JURORS OR THE JURY

The trial judge may discharge the whole jury if certain irregularities occur. These would include the situation where the defendant’s previous convictions are revealed inadvertently during the trial. Such a disclosure would be prejudicial to the defendant. In such a case, the trial would be ordered to commence again with a different jury. Individual jurors may be discharged by the judge if they are incapable of continuing to act through illness ‘or for any other reason’ (s 16(1) of the Juries Act (JA) 1974). Where this happens, the jury must not fall below nine members.

11.4 THE SELECTION OF THE JURY

In theory, jury service is a public duty that citizens should readily undertake. In practice, it is made compulsory, and failure to perform one’s civic responsibility is subject to the sanction of a £1,000 fine.

11.4.1 LIABILITY TO SERVE

In 2010, 373,650 juror summonses were issued and 181,281 people actually served as jurors (see the end of this section for an explanation of the difference in these figures). The JA 1974, as amended by the CJA 1988 and the CJA 2003, sets out the law relating to juries. Prior to the JA 1974, there was a property qualification in respect to jury service that skewed jury membership towards middle-class men. Now, the legislation provides that any person between the ages of 18 and 70, who is on the electoral register and who has lived in the UK for at least five years, is qualified to serve as a juror.

The procedure for establishing a jury is a threefold process:

• An officer of the court summons a randomly selected number of qualified individuals from the electoral register.

• From that group, panels of potential jurors for various cases are drawn up.

• The actual jurors are then randomly selected by means of a ballot in open court.

As has been pointed out, however, even if the selection procedure were truly random, randomness does not equal representation. Random juries, by definition, could be: all male, all female, all white, all black, all Conservative or all members of the Raving Loony Party. Such is the nature of the random process; the question that arises from the process is whether such randomness is necessarily a good thing in itself, and whether the summoning officer should take steps to avoid the potential disadvantages that can result from random selection.

As regards the actual random nature of the selection process, a number of problems arise from the use of electoral registers to determine and locate jurors:

• Electoral registers tend to be inaccurate. Generally, they misreport the number of younger people who are in an area simply because younger people tend to move about more than older people and therefore tend not to appear on the electoral roll of the place in which they currently live.

• Electoral registers tend to underreport the number of members of ethnic minorities in a community. The problem is that some members of the ethnic communities, for a variety of reasons, simply do not notify the authorities of their existence.

• The problem of non-registration mentioned above was compounded by the disappearance of a great many people from electoral registers in order to try to avoid payment of the former poll tax. It has been suggested that the current government’s proposals to alter registration procedure to an individual voluntary process from a compulsory household process would have an even greater impact on the register of voters.

11.4.2 INELIGIBILITY EXCEPTIONS, DISQUALIFICATION AND EXCUSAL

Prior to the CJA 2003, the general qualification for serving as a juror was subject to a number of exceptions.

A variety of people were deemed to be ineligible to serve on juries on the basis of their employment or vocation. Among this category were: judges; Justices of the Peace; members of the legal profession; police and probation officers; and members of the clergy or religious orders. Those suffering from a mental disorder were also deemed to be ineligible. Paragraph 2 of Sched 33 to the CJA 2003 removes the first three groups of persons ineligible, the judiciary, others concerned with the administration of justice, and the clergy, leaving only mentally disordered persons with that status.

This reform came into effect in April 2005. The extent to which ‘ordinary’ jurors will be influenced by contact with solicitors, barristers and judges remains to be seen (assuming that research into such matters is eventually permitted). In any event the provisions of the CJA 2003 as regards eligibility to serve were challenged, as being contrary to Art 6 of the ECHR, in R v (1) Abdroikov (2) Green (3) Williamson (2005), three otherwise unrelated cases. Each of the appellants appealed against their convictions on the grounds that the jury in their respective trials had contained members who were employed in the criminal justice system. The juries in the trials of the first and second appellants had contained serving police officers. The jury in the trial of the third appellant had contained a person employed as a prosecuting solicitor by the CPS. Their proposal was that, as prior to the CJA 2003 there would have been no doubt that the presence of such people on juries would have been unlawful, so their presence in the current cases ran contrary to the need for trials to be free from even the taint of apparent bias.

The Court of Appeal rejected such arguments as spurious, holding that the expectations placed on ordinary citizens in relation to jury service had to be extended to members of the criminal justice system.

However, by a majority of three to two the House of Lords held that the appeals of Green and Williamson should succeed, but that Abdroikov’s appeal must fail. Lords Rodger and Carswell, in the minority held that all appeals should fail. In reaching its decision the majority looked at the reports of previous committees that had been tasked with examining the operation of juries. Thus they referred to the findings of the 1965 committee chaired by Lord Morris of Borth-y-Gest, which recommended that the police and those professionally concerned in the administration of the law should continue to be ineligible. Then in 2001, Auld LJ reviewed the issue and recommended that everyone should be eligible for jury service save for the mentally ill. He recognised that the risk of bias could not be totally eradicated and envisaged that any question about the risk of bias on the part of any juror could be resolved by the trial judge on the facts of the case. His recommendation was given effect by the Criminal Justice Act 2003 s 321. However, as the House of Lords made clear, Auld LJ’s expectation that each doubtful case would be resolved by the trial judge could not be met if neither the judge nor counsel knew that the juror was a police officer or CPS solicitor. The House of Lords recognised that there were situations where police officers and CPS solicitors would meet the tests of impartiality, however, that did not mean they would always do so automatically.

However, according to Lords Rodger and Carswell in the minority, Parliament had endorsed the view that universal eligibility for jury service was to be regarded as appropriate. In reaching that conclusion Parliament had to be taken to have been aware of the test for apparent bias. It must, therefore be taken to have considered that the risk of bias in the case of serving police officers or CPS solicitors was manageable within the system of jury trial. The consequence of the House of Lords majority decision was pointed out by Lord Rodger in the clearest of terms:

I can see no reason why the fair-minded and informed observer should single out juries with police officers and CPS lawyers as being constitutionally incapable of following the judge’s directions and reaching an impartial verdict. It must be assumed, for instance, that the observer considers that there is no real possibility that a jury containing a gay man trying a man accused of a homophobic attack will, for that reason alone, be incapable of reaching an unbiased verdict, even though the juror might readily identify with a fellow gay man. Despite this – if Mr Green’s appeal is to be allowed – the observer must be supposed to consider that there is, inevitably, a real possibility that a jury will have been biased in a case involving a significant conflict of evidence between a police witness and the defendant, just because the witness and a police officer juror serve in the same borough or the juror serves in a force which commits its work to the trial court in question. Similarly, if Mr Williamson’s appeal is allowed, the observer must be taken to consider that the same applies to any jury containing a CPS lawyer whenever the prosecution is brought by the CPS. In my view, an observer who singled out juries with these two types of members would be applying a different standard from the one that is usually applied. For no good reason, the observer would be virtually ignoring the other 11 jurors … your Lordships’ decision to allow two of the appeals will drive a coach and horses through Parliament’s legislation and will go far to reverse its reform of the law, even though the statutory provisions themselves are not said to be incompatible with Convention rights. Moreover, any requirement for police officers and CPS lawyers balloted to serve on a jury to identify themselves routinely to the judge would discriminate against them by introducing a process of vetting for them and them alone. Parliament cannot have considered that such a requirement was necessary since it did not impose it. The rational policy of the legislature is to decide who are eligible to serve as jurors and then to treat them all alike.

The issue of apparent juror bias on account of their occupation was considered further by the Court of Appeal in six conjoined cases in March 2008: R v Khan (2008). The occupations involved were those of serving police officers, employees of the CPS, although on this occasion in a prosecution brought by the Department of Trade and Industry, and prison officers. The judgment of the Court of Appeal was delivered by the then Lord Chief Justice, Lord Phillips in the course of which he explained that, although the Criminal Justice Act 2003 had abolished automatic disqualification from jury service on account of an occupation associated with the administration of justice, it had not made those persons immune to claims of apparent bias and that ‘the nature of some occupations is such that there is an obvious danger that the circumstances of a prosecution will give rise to an appearance of bias in relation to those who belong to them’. In its consideration of the issues, the Court of Appeal distinguished between apparent bias towards a party in the case and apparent bias towards a witness in the case. In the former instance should it become apparent during a trial that a juror is partial then they should be discharged. If the bias only becomes apparent after the verdict, then the conviction must be quashed. However the Court held that apparent bias towards a witness does not, automatically, have those consequences and will do so, only if it would appear to the fair-minded observer that the juror’s apparent bias may affect, or have affected, the outcome of the trial. The fair-minded observer test was established in the House of Lords in Porter v Magill (2001).

As regards serving police officers, the Court of Appeal could find no clear principles for identifying apparent bias from the majority judgments in R v Abdroikov, but went on to hold that although such jurors may seem likely to favour the evidence of a fellow police officer, that would not, automatically, lead to the appearance that they favoured the prosecution. For example if the police evidence was not challenged or was not an important part of the prosecution case, then there would be no reason to suspect bias on the part of the juror. It would only be appropriate to question a conviction for apparent bias if, and only if, the effect of the juror’s partiality towards a fellow officer put in doubt the safety of the conviction and thus rendered the trial unfair.

More specifically, the court rejected the proposition that the mere fact that a police officer had taken part in operations involving the type of offence with which a defendant was charged gave rise, of itself, to an appearance of bias on the part of the police officer. As the court pointed out, police officers are likely to have had experience of most of the common types of criminal offence, not least drug dealing. Finally as regards police jurors, the fact that the jury was told that a defendant had a previous conviction for assaulting a police officer would not of itself raise the issue of apparent bias.

As seen above, in Abdroikov, the majority of the House of Lords held that a juror who was a member of the Crown Prosecution Service had the appearance of bias where they acted as a juror in a case prosecuted by their employer. However, the Court of Appeal distinguished the situation under its consideration from that case in holding that there could be no objection to a member of the Crown Prosecution Service sitting in a case prosecuted by some other authority, in this particular instance the Department of Trade and Industry.

With regard to the possibility of prison guards acting as jurors, the Court of Appeal made it clear that the mere suspicion that a juror might, by reason of employment in a prison where a defendant had been held, have acquired knowledge of that defendant’s bad character could not, of itself, lead an objective observer to conclude that the juror had an appearance of bias. Where the juror had no knowledge of the defendant, there could be no objective basis for imputing bias towards the defendant. Indeed, even actual knowledge of a defendant’s bad character would not automatically result in the juror ceasing to qualify as independent and impartial.

In concluding his judgment, Lord Phillips emphasised the court’s concern with the need to regularise, and thus avoid appeals from, cases raising the issue of juror bias in relation to particular occupations. As he put it:

It is undesirable that the apprehension of jury bias should lead to appeals such as those with which this court has been concerned. It is particularly undesirable if such appeals lead to the quashing of convictions so that re-trials have to take place. In order to avoid this it is desirable that any risk of jury bias, or of unfairness as a result of partiality to witnesses, should be identified before the trial begins. If such a risk may arise, the juror should be stood down … It is essential that the trial judge should be aware at the stage of jury selection if any juror in waiting is, or has been, a police officer or a member of the prosecuting authority, or is a serving prison officer. Those called for jury service should be required to record on the appropriate form whether they fall into any of these categories, so that this information can be conveyed to the judge. We invite all of these authorities and Her Majesty’s Court Service to consider the implications of this judgment and to issue such directions as they consider appropriate.

In an endeavour to maintain the unquestioned probity of the jury system, certain categories of persons are disqualified from serving as jurors. Among these are anyone who has been sentenced to a term of imprisonment, or youth custody, of five years or more. In addition, anyone who, in the past 10 years, has served a sentence, or has had a suspended sentence imposed on them, or has had a community punishment order made against them, is also disqualified. The CJA 2003 makes a number of amendments to reflect recent and forthcoming developments in sentencing legislation. Thus, juveniles sentenced under s 91 of the Powers of Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act 2000 to detention for life, or for a term of five years or more, will be disqualified for life from jury service. People sentenced to imprisonment or detention for public protection, or to an extended sentence under ss 227 or 228 of the Act are also to be disqualified for life from jury service. Anyone who has received a community order (as defined in s 177 of the Act) will be disqualified from jury service for 10 years. Those on bail in criminal proceedings are disqualified from serving as a juror in the Crown Court.

Certain people were excused as of right from serving as jurors on account of their jobs, age or religious views. Among these were members of the medical professions, Members of Parliament and members of the armed forces, together with anyone over 65 years of age. Paragraph 3 of Sched 33 to the CJA 2003 repeals s 9(1) of the JA 1974 and consequently no one will in future be entitled to excusal as of right from jury service.

It has always been the case that if a person who has been summoned to do jury service could show that there was a ‘good reason’ why their summons should be deferred or excused, s 9 of the JA 1974 provided discretion to defer or excuse service. With the abolition of most of the categories of ineligibility and of the availability of excusal as of right, it is expected that there will be a corresponding increase in applications for excusal or deferral under s 9 being submitted to the Jury Central Summoning Bureau (see below).

Grounds for such excusal or deferral are supposed to be made only on the basis of good reason, but there is at least a measure of doubt as to the rigour with which such rules are applied.

A Practice Note issued in 1988 (now Practice Direction (Criminal: Consolidated) [2002] 1 WLR 2870, para 42) stated that applications for excusal should be treated sympathetically and listed the following as good grounds for excusal:

(a) personal involvement in the case;

(b) close connection with a party or a witness in the case;

(c) personal hardship;

(d) conscientious objection to jury service.

However, a new s 9AA, introduced by the CJA 2003, places a statutory duty on the Lord Chancellor, in whom current responsibility for jury summoning is vested, to publish and lay before Parliament guidelines relating to the exercise by the Jury Central Summoning Bureau of its functions in relation to discretionary deferral and excusal. Although the historic office of Lord Chancellor seems to have been preserved, the future role of Lord Chancellors is unclear.

The aim of the guidelines should be to ensure that all jurors are treated equally and fairly and that the rules are enforced consistently, especially in regard to requests to be excused from service, and thus to reduce at least some of the potential difficulties mentioned above. The previous, somewhat antiquated procedure for selecting potential jury members, with its accompanying disparity of treatment, is in the process of being modernised by the introduction of a Central Summoning Bureau based at Blackfriars Crown Court Centre in London. Progressively from October 2000, the new Bureau is using a computer system to select jurors at random from the electoral registers and issue the summonses, as well as dealing with jurors’ questions and requests. It is intended to link the jury summoning system to the national police records system to allow checks to be made against potentially disqualified individuals. However, severe doubts have been expressed as to the accuracy of the police national computer (PNC), which might not only render the checks on juries inaccurate, but might actually contravene the Data Protection Act 1998. When the Metropolitan Police conducted an audit of the PNC in 1999, it was found to have ‘wholly unacceptable’ levels of inaccuracy, with an overall error rate of 86 per cent. In one case in 2000 at Highbury Corner magistrates’ court in north London, a man charged with theft of £2,700 was granted bail on the grounds that the PNC showed that he had no previous convictions. In fact, he was a convicted murderer released from prison on licence.

It has to be stated that, as reported in a parliamentary answer in February 2007, the Secretary of State for the Home Department intimated that later audits carried out in August 2002 had indicated that the general position on data accuracy was far more favourable than had previously been suggested. According to his statement, the exercise found that in 94 per cent of cases, the key information was recorded entirely accurately, and that in the remaining 6 per cent some inaccuracies were found but, in the majority of instances, the inaccuracy was not critical.

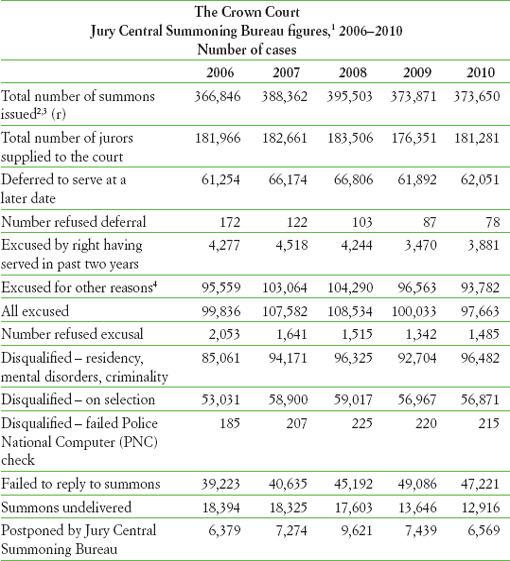

TABLE 11.1 Reproduced from Ministry of Justice Report

Source: Jury Central Summoning Bureau

Notes:

1 Numbers do not add up to the overall total within a given year as the data reflect rolling 12-month periods with ‘carry-over’ rules applied to certain rows in the table. For example, the number of disqualifications reported for a given year may include disqualifications for summons that were issued in previous years.

2 Previously published figures for 2006 to 2009 double counted summons that were re-issued due to a change in court venue. In this publication, these figures have been revised to remove any double counting.

3 This figure represents the number of summons that were issued in a year and not the number of people that actually served on a jury in that year. For example, a person summoned for jury service in 2010, may not actually serve until 2011.

4 Including childcare, work commitments, medical, language difficulties, student, moved from area, travel difficulties and financial hardship.

Statistics relating to juries are contained in the Ministry of Justice ‘Judicial and Court Statistics 2010 report available at: http://www.justice.gov.uk/publications/statistics-and-data/courts-and-sentencing/judicial-annual.htm

In 2010, 373,650 juror summonses were issued. Of these, 97,663 were excused: 3,881 were excused as they had already served in the last two years and 93,782 were excused for other reasons including childcare, work commitments, medical issues, language difficulty, student status, changes in residency, travel difficulties and financial hardship. The number of people who failed to reply to their summons, together with the number returned as undelivered, totalled 49,137, a remarkably high number.

11.4.3 PHYSICAL DISABILITY AND JURY SERVICE

It is to be hoped that the situation of people with disabilities has been altered for the better by the CJPOA 1994, which introduced a new s 9B into the JA 1974. Previously, it was all too common for judges to discharge jurors with disabilities, including deafness, on the assumption that they would not be capable of undertaking the duties of a juror.

Under this provision, where it appears doubtful that a person summoned for jury service is capable of serving on account of some physical disability, that person, as previously, may be brought before the judge. The new s 9B, however, introduces a presumption that people should serve and provides that the judge shall affirm the jury summons unless he is of the opinion that the person will not be able to act effectively.

It would appear, however, that the CJPOA 1994 does not improve the situation of profoundly deaf people who could only function as jurors with the aid of a sign language interpreter. That was the outcome of a case decided in November 1999 that profoundly deaf Jeff McWhinney, Chief Executive of the British Deaf Association, could not serve as a juror. For him to do so would have required that he had the assistance of an interpreter in the jury room and that could not be allowed as, at present, only jury members are allowed into the jury room.