The Formation of Collective Memory about the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands History in China and Japan

Chapter 6

The Formation of Collective Memory about the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands History in China and Japan

Introduction

Claiming disputed territory is a memory project. A memory project manages the content of collective memory by demonstrating to those at present—both domestic and international audiences—how the past has evolved. A memory project can involve people who reconstruct events from the past, such as people’s memory of September 11 (Clark 2002) or a nation’s memory of a past war (Wagner-Pacifici and Schwartz 1991). I study below the official collective memory of the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands constructed by the Chinese and the Japanese governments and official media through an analysis of relevant pages of four official websites hosted by China and Japan.1

In this chapter,2 I review the territorial claims made by the Chinese and the Japanese governments to establish sovereignty over the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the Pacific, examining them in the context of collective memory. Through reviewing the territorial claims made by both governments, the chapter helps answer the first question raised in the introductory chapter of this volume, namely, what gave rise to this particular territorial dispute? The discussions here will also touch upon the second question about sovereignty claims, not about who can make sovereignty claims but about how each side makes them.

These rocky formations known as the Diaoyu Islands for the Chinese and the Senkaku Islands for the Japanese have received extensive news media coverage in East Asia as well as around the world in recent years, with images of activists and patriots from China/Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan protesting and claiming territorial rights of their respective countries. What is behind all this fervent patriotism on both sides of the dispute? Where does people’s knowledge of territorial ownership come from? This chapter focuses on the construction of territorial ownership as a collective memory project by studying two official sources of information for collective memory formation in China and Japan with regard to the history of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands—one governmental and one news media.

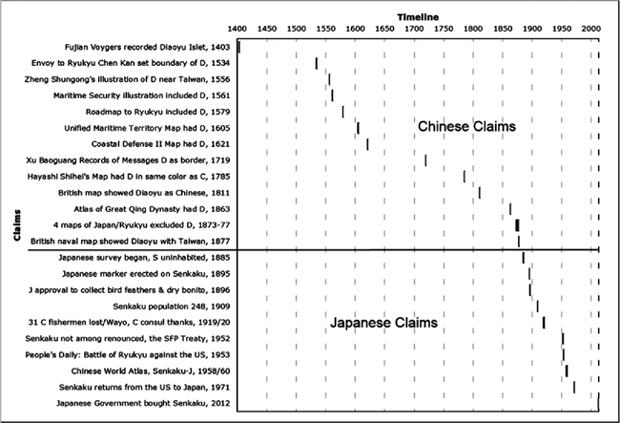

Analyzing the description of the history relevant to the islands found at the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s and the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s websites and at the People’s Daily and the Asahi Shimbun (literally, Morning Sun Newspaper) websites,3 the chapter seeks to understand the differences in collective memory formation in the two countries. Through an analysis of the mentions of historical events relevant to the islands, I have found that China and Japan stage their respective territorial claims by emphasizing and resorting to different periods of history. The chapter shows that to produce a convincing territorial claim, both China and Japan form collective historical memory about the islands through enhancing rhetorical force, resonance, and range of reference in memory formation.

A Memory Project for Territorial Claims

Definition of Memory Projects

Memory projects present and preserve images of the past relevant to a particular collective purpose. They are “concerted efforts to secure presence for certain elements of the past” (Irwin-Zarecka 1994, p. 13). Put differently, “[m]emory projects mobilize energy and resources for the purpose of stabilizing images of the past” (Schwartz 1995, p. 267). Thus, memory projects are collective, sometimes official, efforts to mobilize human and other kinds of resources with the aim to create and maintain a set of stable images of the past for the purpose of the present stakeholders.

Territorial Claims as Memory Projects

Governments resort to means that are useful for them to make a territorial claim. Legal arguments are an obvious one, as Scoville shows in Chapter 4 of this book. It is also obvious, and common, to make a territorial claim based on history, or at least what is presented as history and what people in a nation remember as history. Hence, memory projects create and maintain a kind of collective memory that a group of individuals may share, but may not be shared by other groups. This simple fact suggests that collective memory is selective; in fact, it is always selective (Halbwachs 1992).

What people remember collectively is consequential because people’s knowledge, or rather, their belief of having certain knowledge, can affect and govern their behavior, collective or not. In that sense, a memory project manages and controls what we remember collectively, and may influence our behavior. There are two kinds of official memory projects—those that are sponsored and controlled by the government and those that are initiated by nongovernmental organizations. I am concerned in this chapter with both types. Sometimes the line becomes blurry when a nongovernmental organization is not only recognized by the government but perhaps supported by it, directly or indirectly. The products of memory projects are plenty: textbooks, memorials, national anthems, and so on. Wagner-Pacifici and Schwartz (1991) analyzed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial as a collective memory project and Liao, Zhang, and Zhang (2011) studied the Chinese national anthem as a collective memory project (even though the two papers did not use that specific term and had different research aims). It goes without saying that some collective projects are more effective than others, just like any other kinds of projects. Thus, we need a way for analyzing the effectiveness of memory projects.

Liao (2010) and Liao, Zhang, and Zhang (2010) demonstrated the usefulness of Schudson’s (1989) cultural object typology for studying collective memory symbols. Collective memory projects utilize collective memory and cultural symbols; cultural symbols are cultural objects. The efficacy of a cultural object or a collective memory project, whether about how we remember the Vietnam War or how one makes a territorial claim, varies from impotency to omnipotence when the cultural object or the collective memory project is presented to a given population at a given historical time.

For Schudson (1989), there are five dimensions for analyzing the potency of a cultural object—retrievability, rhetorical force, resonance, institutional retention, and resolution. A cultural symbol is retrievable if one viewing it recognizes it and knows what it is; culture must be able to reach a person if it is to influence the person. If a symbol is seen by people, what renders the symbol memorable and powerful? A symbol that engages the viewer’s attention is said to have more rhetorical power than the one that cannot. Sometimes rhetorical power is related to status: a high-status source may be more persuasive than a lower-status one. However, this can be treacherous ground because a high-status source may backfire for subordinate groups. A cultural symbol must have resonance to have efficacy. For example, the political use of symbolism by rulers cannot be successful unless the symbolism connects to underlying native traditions, thereby resonating among those holding the traditions. A cultural symbol has potency when it has institutional retention. The institutionalized symbols have social relational basis in which meaning is enacted, as compared with a fad, which has no such social relational backing, thus lacking institutional retention. Finally, a cultural symbol has greater resolution if it is more likely to influence people’s behavior and action. Obviously, a cultural symbol is at its most potent level if it scores high in all five dimensions; conversely, it has little efficacy if it registers low in the five aspects. The efficacy of cultural objects as objects of collective memory can thus be understood, and analyzed, in terms of these five dimensions.

Of the five dimensions, two can be applied directly to the analysis of memory projects for making territorial claims. They are rhetorical force and resonance. We are not interested in resolution because that refers to the consequences of a memory project, a topic beyond the scope and concerns of this chapter. All official collective memory projects have institutional backing to the extent that there is no discernible variation between projects. For the current consideration the nation states of China and Japan are behind their memory projects. Retrievability matters little here because historical references, though perhaps not retrievable initially, can be learned by people. In fact, that is indeed a main purpose of such memory projects—getting people to know and memorize certain historical events and references so that these events and references become immortalized in collective memory through a memory project. In sum, retrievability, institutional retention, and resolution are of no concern in the current study. However, historical references do vary in terms of their rhetorical power and resonance, largely due to the quality and type of events referred to and the manner in which they are referred to, and will be subject to analysis below.

In addition to rhetorical power and resonance, let us add another dimension for the analysis of territorial claim memory projects, range of reference. Other things being equal, if a nation can establish ownership of a certain territory for a longer range of history, supported by specific event references, the claim will be stronger than, say, another nation whose range of reference is rather short, at least for the consumption by its people if not for the consideration by international law specialists. In the pages below, I will study and compare the memory projects of making Diaoyu/Senkaku territorial claims in the dimensions of rhetorical power, resonance, and range of reference. Taken together, the use of historical references to events in the past can be a powerful tool for managing current problems and disputes. Just as Hobsbawm (1972) summarized, the past remains the most effective tool for dealing with constant changes (shall we say challenges) in the present.

Hypotheses

Following the theoretical discussion in the section above, one may surmise that both governments must try and increase the efficacy of their respective collective memory projects. To do so, they must attempt to strengthen the rhetorical power, enhance the resonance, and lengthen the range of reference of the collective memory objects in their collective memory projects. To understand these collective memory project efforts about the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, I empirically assess the three dimensions of rhetorical power, resonance, and range of reference of the collective memory objects presented at the official Chinese and Japanese internet websites, through the following three hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

To increase rhetorical power, the parties involved in the dispute employ specific references to verifiable historical events with as much detail as possible. When a historical event is verifiable in publically available sources, the event is more believable, thus having greater rhetorical power. Similarly, when more detail is supplied for describing a historical event, the event becomes more believable, thus having greater rhetorical power.

Hypothesis 2

To increase resonance, a party involved in the dispute reports the wrongdoings by the other party that may have taken place in the past in regard to the disputed territory. A well-worn response to wrongdoing is that it deserves punishment (Kleinig 2011). Words of accusing the other party’s wrongdoings and believing they deserve punishment can spread easily and quickly and getting more people into such beliefs. Therefore, reports of wrongdoings tend to increase resonance.

Hypothesis 3

To increase range of reference, the parties involved in the dispute employ historical references in as long a range as possible. When a party establishes historical territorial claims by using a range of historical references covering 500 years, the claim becomes more effective than using a range of such references covering just 10 years, other things being equal. Furthermore, density in the range of references may also help increase the efficacy of collective memory. That is, in the same range of 100 years, 20 specific references would be more effective than 10, other things being equal.

These three hypotheses can also be assessed comparatively in an empirical analysis. In fact, it will be informative to see which party may fare better in some but not all three respects, enabling us to achieve an overall understanding of the efficacy of a certain collective memory project. I will evaluate the hypotheses with the internet data described below.

Data

To study the efficacy of the collective memory projects on both the Chinese and the Japanese sides, I analyzed four websites, two in each country. The selection of data was based on the two criteria (excluded from the analysis) for assessing the efficacy of collective memory or cultural symbols discussed in Liao (2010) and Liao, Zhang, and Zhang (2010): retrievability and institutional retention. In this electronic age, websites enjoy the best kind of retrievability of the highest order. A website is open and freely available to anyone around the world with a computer or a mobile device and internet access. The segments of a population with the highest percentage of internet usage tend to be those who are more important for a government to get on their side and who tend more likely to participate in collective action—the younger population and the better educated.

An official website, either hosted by a government or by an official nongovernmental organization, has by definition institutional retention because the organization that hosts the website will make certain the website is maintained for the self-interest of the organization. Thus, using the criteria of retrievability and institutional retention, the sites selected are, for the Chinese data: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs ( , http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_chn/) and People’s Daily–based website (

, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_chn/) and People’s Daily–based website ( , http://people.com.cn/); for the Japanese data: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (

, http://people.com.cn/); for the Japanese data: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs ( , http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/index.html) and Asahi Shimbun Digital (

, http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/index.html) and Asahi Shimbun Digital ( , http://www.asahi.com/). These four websites were studied in the two to three months leading to mid-April 2013.4

, http://www.asahi.com/). These four websites were studied in the two to three months leading to mid-April 2013.4

The pages hosted by the foreign ministries and used in the study are mostly in English except one by the Chinese ministry, which is in Chinese only. The webpages hosted by the People’s Daily newspaper are bilingual while the pages hosted by Asahi Shimbun