The First Amendment: History and Application

The First Amendment: History and Application

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of opinion is that it is robbing the human race, posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth; if it is wrong, they lose what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.1

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights

First Amendment Political Philosophies

Overview

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution impacts virtually all laws in the fields of advertising, broadcasting, journalism, and public relations. This chapter introduces the basic concepts needed to understand when and how the First Amendment guarantees freedom to communications practitioners and when it restricts the applicability of other laws. Rather than present a chronology of First Amendment interpretations, this chapter is organized around four major concepts that facilitate understanding the meaning and application of the political philosophies that guide interpretation of the First Amendment’s provisions by the U.S. Supreme Court.

We begin with an explanation of the difference between civil liberties and civil rights. Familiarity with these concepts is essential to understanding that the First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech and press, not a right of free press or a right of free speech. Furthermore, we explain that the First Amendment does not limit actions by corporations, individuals, and other nongovernmental entities.

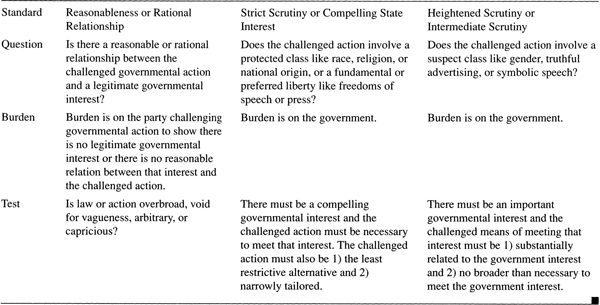

Finally, we describe the standards of judicial review that have been used to determine which of our freedoms is important enough to withstand governmental intrusion. These standards and their applications to laws and other governmental actions that curtail free speech and press provide the substance of constitutional interpretation as it is applied by the U.S. Supreme Court today.

This discussion of history and systems of interpretation is provided to give students and practitioners a foundation for understanding how freedom of speech and the press is enforced and balanced against other liberties and rights. Practical applications of First Amendment interpretations to government regulation of mass communications practitioners are discussed in the next chapter.

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights

Many students and practitioners of mass communications believe the First Amendment requires government to protect their interests or that they, because of their profession, stand in a “special place” in relation to the law. This belief may be the product of professional arrogance or it may result from a simple misunderstanding of what is guaranteed by the First Amendment. To really appreciate what legal actions are required or prohibited by the First Amendment, one must understand that the First Amendment provides “civil liberties,” not “civil rights.”

The distinctions between the concepts “civil liberties” and “civil rights” have evolved over the history of the United States. The first 10 Articles of Amendment to the U.S. Constitution are commonly referred to as the Bill of Rights. However, the term Bill of Rights is a misnomer because those amendments describe freedoms and liberties, not rights. Freedoms or liberties are exercised by individual citizens without restrictions from government. A freedom limits the actions of a government vis-à-vis its citizens. It does not actually require any governmental action.

Prior to the American Revolution in 1775, most governments in the world were monarchies or oligarchies and were more often than not extremely despotic. People had little control over their daily lives and the average citizen was completely subservient to the monarchy or anyone to whom the monarch had granted authority. Although there were occasional exceptions to this form of rule,2 the vast majority of the people in the world suffered under tyrannical forms of government and had absolutely no personal freedoms or rights.

The principles of democracy that underlay the formation of the U.S. government began with the brief forays into self-governance described by the writings of ancient Greek and Roman historians and philosophers. Eventually, ideas about democracy, individual freedoms, and natural human rights found their way into the writings and discourse of 16th-and 17th-century political philosophers like Thomas Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The writings of these men clearly influenced Thomas Jefferson when he penned the Declaration of Independence in 1776. That document laid the foundation for a sense of civil liberty that is reflected in the U.S. Constitution. In particular, several phrases in the Declaration of Independence make it obvious that the founders of our government intended to create a government that was prohibited from restricting its citizens’ liberties. Most obvious among these is the assertion of unalienable rights.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created Equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government. . . .3

In the Declaration of Independence, the term unalienable Rights referred to “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” However, by the time the Bill of Rights was ratified on December 15, 1791, there was a much more extensive listing of our “rights.” It was also clear that the framers of the Constitution did not intend, by specifically including some rights within the language of the Bill of Rights, to exclude other personal rights necessary for independent civilized thought and action. According to the Ninth Amendment, “The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”4

Following the U.S. Civil War, the Fourteenth Article of Amendment was ratified in 1868. It said, in part,

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.5

This amendment has been interpreted to impose two obligations on the states. First, it compels the states to provide “civil rights” for their citizens. Second, it provides the citizens of each state with “civil liberties.”

The civil rights obligation means the states have an affirmative duty to protect their citizens from infringement of some of the rights inuring to them by virtue of their citizenship in the United States. Given the historic context of the Fourteenth Amendment, these obligations have typically involved rights that were denied in states of the former Confederacy, such as freedom from slavery, and voting and educational rights for minority citizens.

The state’s obligation to recognize civil liberties arises from the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution6 and the Fourteenth Amendment. Taken together, these limit what either the national government or the state governments may do to violate citizens’ freedoms described in the Bill of Rights.

Thus, the term civil liberty has become synonymous with individual liberties or freedoms against which neither the national nor state government may encroach. The term civil rights refers to privileges and immunities guaranteed to U.S. citizens, which the national government and the individual state governments must protect from arbitrary infringement. In the case of civil liberties, government action is prohibited or limited; in the case of civil rights government action is required. The obligation of the national government to protect civil rights is specified in the wording of seven separate amendments to the U.S. Constitution, each of which end with the words, “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”7

The guarantees of free speech and free press described in the First Amendment are civil liberties, not civil rights. The First Amendment says, “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”8 Neither the national government, nor the state governments are required to take any action to protect those liberties. Rather, the governments’ obligations are to avoid doing anything that might infringe free speech or press. Because the government is not obligated to take action, there are no laws, based on the First Amendment, that restrict the conduct of any private individual or corporation. In other words, private citizens and private companies are within their legal rights when they deny free speech or limit press freedoms.

Bill of Rights History

Whether civil rights or civil liberties, the states are not required to provide all of the freedoms described in the Bill of Rights. Recognizing how concepts from the Bill of Rights are imposed on states will help explain how conflicts between state laws and First Amendment liberties are resolved.

For well over 100 years, the Bill of Rights was interpreted by the courts to apply only to the actions of the U.S. government, and not to the individual sovereign states.9 Even after ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, the U.S. Supreme Court failed, for some time, to recognize that any of the basic rights or liberties stemming from the Bill of Rights restricted actions of the individual states.10 In fact, it was not until the end of the 19th century that the Supreme Court began to impose the basic requirements of the Bill of Rights on both the federal and individual state governments.

Many in mass communications think the First Amendment and its assurances regarding free speech and free press are now and have always been the paramount freedoms in the Bill of Rights. However, a review of U.S. Supreme Court decisions shows the concepts of “freedom of speech” and “freedom of the press” did not come to have any significant meaning until the 1920s and 1930s. The idea that these rights should be considered clear limitations on governmental actions by either the national or the state governments evolved fairly slowly.

The notion that freedom of speech ought to be recognized as a fundamental liberty was first enunciated by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 1925 decision in Gitlow v. New York.11 By 1927, freedom of speech began to receive effective implementation, rather than simply rhetorical or philosophical support.12 In 1931, in its decision in Near v. Minnesota, freedom of the press from prior restraint was first formally recognized as a fundamental freedom subject to full constitutional protection from restriction by state laws.13 The process by which the U.S. Supreme Court recognizes a specific freedom as preferred or fundamental so that the freedom is given constitutional protection from state government intrusion was called “a process of absorption” by Justice Cardozo in 1937.14 This process of absorption is labeled incorporation in the social sciences.

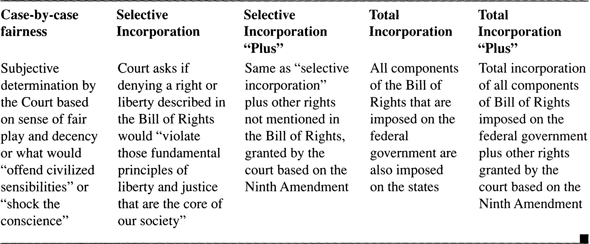

Principles of Incorporation

There are at least five principles or paradigms propounded by political scientists to describe the process of incorporation. Each of these paradigms is based on the history of its development, the composition and activism of the U.S. Supreme Court, the wording of the case decisions and dissenting opinions, and the issues or thematic content of the cases chronologically.15 These paradigms have been grouped by political scientists and named according to the dominant characteristic or judicial philosophy running through a body of cases. Although different titles may be applied, the five paradigms that dominate application of incorporation are (a) case-by-case fairness, (b) selective incorporation, (c) selective incorporation “plus,” (d) total incorporation, and (e) total incorporation “plus.”16 These are summarized in Exhibit 3.1.

Exhibit 3.1. Principles of Incorporation. (What components of the Bill of Rights apply to the states?)

Case-by-Case Fairness

Some of the first cases following ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment appeared to recognize that individuals born or naturalized in the United States should have the same privileges and immunities regardless of their state of residence. However, very quickly the Supreme Court began to seek a doctrine or test to distinguish those “liberties” without which one could not be fairly said to have received due process of law. This decision-making technique is called the case-by-case fairness paradigm of incorporation. Case-by-case fairness was totally subjective and was based on the whims of the majority Total incorporation of all components of Bill of Rights imposed on the federal government plus other rights granted by the court based on the Ninth Amendment of justices serving on the high court at any time. It was a “shoot-from-the-hip” form of jurisprudence that looked at the governmental action, process, or outcome complained of by an individual appellant to determine whether the person had received whatever process seemed fair. The test, if any, used by the court in these cases was whether or not the governmental action “offended civilized sensibilities,” “shocked the conscience,” or went beyond a community’s social sense of “fair play” or “decency.” These cases apparently had to reach some emotional cord with a majority of the justices before the decision would require a state to recognize an individual citizen’s rights or liberties.17

It is interesting to note that economic interests in property and the right to enter into a “contract,” no matter how unconscionable or lopsided the terms and bargaining power, were the kinds of “liberties” first incorporated or imposed on the states by the Supreme Court using this case-by-case fairness test.

Selective Incorporation

The selective incorporation paradigm of absorption by the Fourteenth Amendment says that the states are obligated to grant only those rights and liberties included in the Bill of Rights that are fundamental principles of liberty. Justice Cardozo first described this principle in his opinion in Palko v. Connecticut. The case involved a Fifth Amendment double-jeopardy issue. The appellant, who received a death sentence in a second trial, argued that whatever would be a violation of the original Bill of Rights, if done by the federal government, would be equally unlawful if done by a state. Cardozo responded that there is no such requirement. He said the question to be asked and answered when deciding what components of the Bill of Rights should be incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment and imposed on the states is, “does it violate those fundamental principles of liberty and justice which lie at the base of all our civil and political institutions?”18 He went on to say that rights and liberties such as the right to trial by a jury of 12, freedom from double jeopardy, and the right to indictment by grand jury are not so “rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.”19

The Court then affirmed a state supreme court judgment that allowed a defendant, once tried and convicted of a lesser charge of second-degree murder involving a life sentence, to be retried by the state until it secured a capital conviction of first-degree murder, so long as the trial is “error free” for both sides.

Applying the selective incorporation paradigm, Cordozo did say, in dicta, that free speech and free press were fundamental liberties and the Fourteenth Amendment required their protection by the states.20 Using this version of the selective incorporation standard, the court found a citizen of any state has the absolute right to speak and complain about not receiving his or her constitutional immunity from double jeopardy—all the way to the gallows. The Fifth Amendment prohibition against double jeopardy was not recognized as a “fundamental freedom” requiring application to state trials until the 1969 case of Benton v. Maryland.21

Selective Incorporation “Plus”

The selective incorporation “plus” paradigm for deciding what parts of the Bill of Rights are imposed on the states by the Fourteenth Amendment is similar to the selective incorporation principle described by Justice Cordozo. It too favors freedoms that are seen as fundamental or rooted in our traditions and conscience. Selective ––incorporation “plus” expands the parameters of selective incorporation to include rights and liberties not actually mentioned in the Constitution or the Bill of Rights.

The Ninth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution says, in its entirety, “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”22 Using authority it finds in the Ninth Amendment, the U.S. Supreme Court is free not only to pick and choose from among the various clauses and portions of the Bill of Rights, but also to formulate or acknowledge additional rights not found anywhere in the Constitution. Using the principle of selective incorporation “plus,” any right or freedom the court defines as a fundamental right can be absorbed by the Fourteenth Amendment and used to restrain state actions.

Total Incorporation

Under the total incorporation paradigm any right or liberty mentioned in the Bill of Rights should be applied to the states if there has ever been a court action applying that right or liberty to the federal government. Simply put, under the principle of total incorporation, the states and federal government have exactly the same obligations to honor rights and liberties of their citizens.

Total Incorporation “Plus”

The total incorporation “plus” paradigm expands total incorporation just as the selective incorporation “plus” paradigm expanded selective incorporation. Under this paradigm, all of the provisions of the Bill of Rights applied to the federal government are also applied to the states. In addition, as society changes, any additional rights or liberties imposed on the federal government are also applied to the states even if those rights or liberties were not mentioned in the Constitution or Bill of Rights.23

A famous line from the comedy duo of Laurel and Hardy seems most appropriate to summarize the various theories of incorporation applied by the U.S. Supreme Court: “What a mess you’ve gotten us into now, Stanley!” One cannot simply read the Constitution and its amendments and know what rights or liberties must be honored by the states. Regardless of the intent of the framers, through its interpretation and the power of judicial review, the U.S. Supreme Court has applied some provisions of the Bill of Rights to the states while permitting the states to avoid recognizing other liberties and freedoms. Exhibit 3.2 shows the components of the Bill of Rights that states must honor. Freedoms and liberties the states are not required to recognize include all of the provisions of the Second Amendment, dealing with bearing arms; all of the Third Amendment, dealing with quartering of soldiers in individual citizens’ homes; the Fifth Amendment right to be indicted by a grand jury in a capital or infamous crime; all of the Seventh Amendment, dealing with jury trials in suits at common law; and the first two clauses of the Eighth Amendment, dealing with the rights against excessive bail and against excessive fines.

Exhibit 3.2. Selective Incorporation.

Rights and freedoms identified in the Bill of Rights that states are not required to honor

Second Amendment

Right to bear arms, militia

Third Amendment

Prohibits quartering soldiers in private homes

Fifth Amendment

Indictment by grand jury

Seventh Amendment

Trial by jury in civil matters

Eighth Amendment

Prohibits excessive bail and fines

Rights and freedoms identified in the Bill of Rights that states are obligated to honor

First Amendment

Free Speech–Fisk v. Kansas, 21A U.S. 380 (1927)

Free Press–Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931)

Freedom of Religion–Hamilton v Regents of U. of Calif., 293 U.S. 245 (1934)

Freedom of Assembly–DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937)

Separation of Church & State–Everson v. Board of Ed. 330 U.S. 1 (1947)

Freedom of Association–NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958)

Fourth Amendment

No unreasonable search and seizures–Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949)

Fifth Amendment

Just compensation–Missouri Pacific Rwy Co. v. Nebraska, 164 U.S. 403 (1896)

No Self-Incrimination–Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964)

No double jeopardy–Benton v. Maryland, 395 U.S. 784 (1969)

Sixth Amendment

Fair Trial and right to counsel–Powell v Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932)

Right to cross-examine witnesses–Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965)

Right to impartial jury–Parker v. Gladden, 385 U.S. 363 (1966)

Right to speedy trial–Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967)

Eighth Amendment

No cruel and unusual punishment–Robinson v. Calif, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)

Ninth Amendment

Right to vote–Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)