The Euro Regulations

A. Introduction

The preceding chapters have considered the consequences of the Treaty on European Union and other questions of a relatively ‘high level’ nature. It is now necessary to focus on the more detailed legal framework for the introduction of the single currency.

It has been noted earlier that, ultimately, two separate Council Regulations were made in order to provide the initial framework for the use of the euro. Plainly, it would have been preferable if the required ‘code’ for the single currency could have been set out in a single document. It is therefore pertinent to ask—why was this unfortunate division of labour found to be necessary? In order to answer this question, it is proposed to consider the two regulations in chronological order.

B. Council Regulation 1103/97

The first Regulation—Council Regulation 1103/971 came into effect in June 1997.2 The Regulation was made under Article 308 (formerly Article 235) of the EC Treaty. The provision is now to be found in Article 352, TFEU and reads as follows:

If action by the Union should prove necessary, within the framework of the policies defined in the Treaties, to attain one of the objectives set out in the Treaties, and the Treaties have not provided the necessary powers, the Council, acting unanimously on a proposal from the Commission and after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament, shall adopt the appropriate measures.3

This immediately gives rise to two questions. First of all, why was it necessary to introduce a Regulation dealing with the euro some eighteen months before the single currency was due to be created? Secondly, why was it necessary to invoke Article 308, when Article 123(4) of the Treaty4 already contained a power to issue regulations for the rapid introduction of the single currency? The latter point assumes a certain importance when it is borne in mind that Article 308 (now Article 352) could not be used where an explicit and appropriate Treaty provision is available to deal with the matter in hand.5

As to the first question, it was felt necessary to provide legal certainty so that financial institutions and other organizations involved in or affected by the changeover could plan their preparations well in advance.6 Proper advance planning would allow for a more smoothly conducted changeover when the single currency came into being. The nature and extent of the legal certainty actually provided by this Regulation will be discussed at paragraph 29.20.

Whilst the answer to the first question is therefore founded mainly on practical considerations, the answer to the second lies in a more technical approach to the terms of the EC Treaty. Article 123(4) of the Treaty allows the Council—acting on a proposal from the Commission and after consulting the European Central Bank (ECB)7—to issue the necessary measures with the unanimity of the Member States without a derogation. Now, as noted earlier,8 a Member State which did not qualify for single currency membership at the beginning of the third stage of European Monetary Union (EMU) was referred to in the Treaty as a ‘Member State with a derogation’. However, the identities of the participating and non-participating Member States had not been ascertained in June 1997 when Regulation 1103/97 was to be made. Indeed, those Member States were only finally identified on 3 May 1998, and consequently the power to make regulations conferred by Article 123(4) could not be exercised until that date; only at that point would it become possible to name these Member States ‘without a derogation’ whose ‘unanimity’ was required for these purposes. Turning to considerations of a rather more national character, it should be said that much of the pressure for legal certainty in this area emanated from the London financial markets, which feared for the sanctity of contracts whose effectiveness spanned the changeover period.9 Yet, by this time, it was tolerably clear that the United Kingdom would not participate in monetary union. Even if it had been possible for the Community to invoke Article 123(4) as a basis for the regulation at that stage, this would still have been of no assistance to the London markets, for regulations issued under Article 123(4) have no application in this country for so long as the United Kingdom remains outside the eurozone.10 This particular point has consequences for the status of the euro in the United Kingdom, to which it will be necessary to return. But the present discussion has hopefully demonstrated that Article 308 provided the only basis upon which a regulation dealing with the euro could then be made in a manner which would be legally effective in all Member States, whether or not they would ultimately move on to the Third Stage of EMU.11

It follows that the legal basis of Regulation 1103/97 is secure, even if perhaps derived from an unexpected source. But what did the Regulation achieve? In broad terms, the Regulation is directed to three main issues upon which early clarification had been sought, namely (a) the consequences of monetary union for the ECU; (b) the continuity of transitional contracts which ‘spanned’ the introduction of the euro; and (c) the calculation and rounding of applicable conversion rates.

Some of the points addressed in the Regulation12 will be considered in greater depth in more specific contexts, but it is appropriate here to provide a brief description of the main provisions:

(a) It is confirmed that references in any legal instrument13 to the ECU are to be replaced by a reference to the euro on a one-for-one basis.14 As noted previously, in accordance with the terms of the Madrid Scenario, the ECU was merely being renamed ‘euro’ and as a result, the one-for-one basis had necessarily to follow. Where a legal instrument referred to the ECU without further explanation, it was presumed that this referred to the ‘official’ ECU, although this presumption was rebuttable if the parties had a contrary intention.15

(b) It is confirmed that the introduction of the euro will not result in the discharge of any legal instrument, nor will it alter any of the terms of such an instrument or create any unilateral rights of termination. Parties were, however, allowed to include in their contracts any provision specifically allowing for termination of the contract, if they wished to do so.16

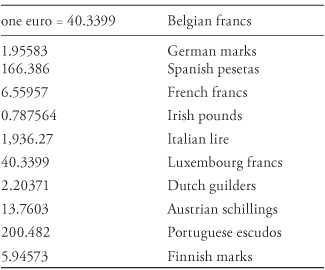

(c) Finally, certain rounding and conversion points are addressed. In particular (i) the conversion rates to be adopted on 1 January 1999 were to be expressed as one euro compared to a set amount of the relevant legacy currencies;17 (ii) the conversion rates were not to be rounded or truncated when making calculations, since this would inevitably lead to distortions;18 (iii) for the same reason, conversions between separate legacy currencies had to be achieved ‘through’ the euro, and the use of inverse rates or alternative methods of calculation were prohibited (unless they produced the same results);19 and (iv) provision was made for rounding of odd amounts to the nearest cent.20

It should be said that point (c) in paragraph 29.08 represents a fairly simplistic description of a set of conversion/rounding rules which could be relatively difficult to apply in practical situations.21 However, the detailed mathematics are fortunately not of concern in a book of this character. Rather, it is more relevant to note that these rules—taken together with the substitution rates adopted by further regulations with effect from 1 January 1999—provide the ‘recurrent link’ between the respective legacy currency and the euro.22 To those of a conservative mindset, it is, perhaps, reassuring to note that a project as vast and as revolutionary as monetary union in Europe still had to have recourse to long-established principles and precedents.23

C. Council Regulation 974/98

It has been noted that Council Regulation (EC) 1103/97 applies to all Member States, even if they currently remain outside the eurozone. By contrast, Council Regulation (EC) 974/9824 applies only within the participating, eurozone Member States.25 It will be necessary to return to this distinction in other contexts.26 First of all, however, the key contents of the Regulation must be described. As will be seen, a number of its provisions must be regarded as the lex monetae of the eurozone Member States. Indeed, the opening sentence of the introductory preamble states that ‘this Regulation defines monetary law provisions of the Member States which have adopted the euro’. EU law accordingly now provides the sole source of the monetary law of participating Member States, since the delegation of monetary sovereignty to institutions created by the Treaties is complete, unconditional, and irrevocable.27

The Regulation came into force on 1 January 1999;28 it includes four main operative parts dealing with the substitution of the euro, the transitional period, the introduction of euro notes/coin, and certain final provisions applicable from the end of the transitional period. Each of these areas must be examined separately.

Substitution of the euro

Part II of the Regulation comprises Articles 2, 3, and 4 and deals with the substitution of the euro for the currencies of the participating Member States. It is appropriate to reproduce Articles 2 and 3 of Regulation 974/98 in full:

Article 2

With effect from the respective euro adoption dates, the currency of the participating Member States shall be the euro. The currency unit shall be one euro. One euro shall be divided into one hundred cent.

Article 3

The euro shall be substituted for the currency of each participating Member State at the conversion rate.

These straightforward provisions—expressed with great clarity and admirable brevity—lie at the heart of monetary union. They emphasize that the euro has been the sole currency of the participating Member States since 1 January 1999,29 even though no euro notes/coins were available in physical form at that time, and even though, as a necessary consequence, the available forms of legal tender differed across the various parts of the eurozone.30

It may be inferred from Article 3 that, whilst national notes/coins continued to circulate, these so-called ‘legacy currencies’ would merely ‘represent’ the euro at the substitution rates ascertained, and irrevocably fixed pursuant to the provisions of the EC Treaty and regulations made under it.31 The same point is, however, reinforced by Article 9 of the same Regulation.32

Article 4 of the Regulation confirms that the euro is the unit of account both of the ECB itself and of the central banks of the eurozone Member States.

Transitional period

Articles 5 to 9 of Regulation 974/98 contain transitional provisions, dealing with the initial introduction of the euro and its relationship to legacy currencies which were to be substituted by the new unit. Perhaps the most important aspect is the creation of a ‘transitional period’.

When the euro was originally created, the transitional period was the three-year period beginning on 1 January 1999 and ending on 31 December 2001.33