THE CONTEMPORARY ROLE, SCOPE AND POWERS OF THE EXECUTIVE

10

The contemporary role, scope and powers of the executive

10.1 Defining the executive: Ministers, Government departments and public bodies

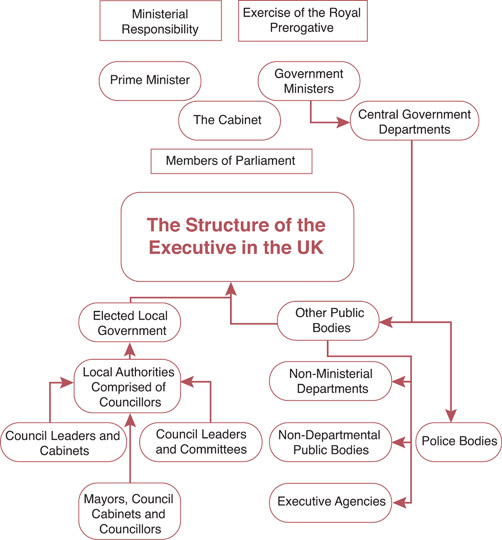

10.1.1 The huge scope of the executive in the United Kingdom today is a complex feature of the constitution, and the executive is the principal means of governance in the country – indeed, it is the entire system of government, in most senses of the term.

The Prime Minister and the Cabinet

10.1.2 The office of Prime Minister (PM) is a historical creation. The earliest statutory basis of the position was the provision of a salary (Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975). The first individual to occupy what we now regard as the post of PM was William Walpole.

10.1.3 By the 1830s a structure of ministerial government with departmental responsibilities, under the leadership of an elected Party leader, was established.

10.1.4 The PM today retains personal control of many key responsibilities of Government, which can be exercised under the prerogative:

- • the right to nominate the Government;

- • the control of the Cabinet agenda;

- • election of the Lord Chancellor; and

- • Chair of Cabinet Committees.

10.1.5 The question most commonly raised with regard to the PM is the extent to which such a concentration of power in the hands of one individual is appropriate in a democracy, and whether there are sufficient controls on the exercise of this power.

10.1.6 One recently created check on the conventional powers of the PM is the shift from the ability of the holder of that office to request the Monarch dissolve Parliament, thereby triggering a General Election, to a system of regularly elected Parliaments every five years, under the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act 2011. (Though there is still a system in place under the 2011 Act for triggering ‘early’ General Elections if the Government of the day loses the confidence of the House of Commons, by May 2015, at the time of writing, this had not been used during the period of the 2010–15 Coalition Government led by David Cameron of the Conservative Party.)

Government Ministers and their departments

10.1.7 The Cabinet of Government Ministers in its modern form is derived from the ancient circle of advisers to the Monarch. It was not until the 19th century that clear areas of ministerial responsibility at Cabinet level emerged.

10.1.8 The modern Cabinet is selected by the PM; typically, its membership numbers around 20. In addition to the Lord Chancellor, the Secretary of State for Justice and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, each post represents a Department of State designated as the PM determines.

10.1.9 The Cabinet functions as a policy forum and as a means of coordinating departmental strategies.

10.1.10 A key criticism of modern Cabinets is the extent to which they have become a ‘rubber stamp’ for policy-making by the PM rather than a collective decision-making body.

10.1.11 The Cabinet’s timetable of meetings is determined by the PM. There is no requirement that a full Cabinet take key decisions. For example, Margaret Thatcher controversially took decisions in the Falklands War without summoning a full Cabinet.

10.1.12 There can be up to 33 attendees at the Cabinet, at the time of writing in May 2015, although the core Cabinet membership consists of:

- • the Prime Minister,

- • the Deputy Prime Minister (or the First Secretary of State, in the nomenclature used by the current Conservative Government of 2015);

- • the Leader of the House of Commons,

- • the Chancellor of the Exchequer;

- • the Secretary of State for the Home Department (known as the Home Secretary);

- • the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs (known as the Foreign Secretary);

- • the Lord Chancellor;

- • the Secretary of State for Justice;

- • the Secretary of State for Defence;

- • the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills;

- • the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions;

- • the Secretary of State for Health;

- • the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government;

- • the Secretary of State for Education;

- • the Secretary of State for International Development;

- • the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change;

- • the Secretary of State for Transport;

- • the Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs;

- • Chief Secretary to the Treasury;

- • the Secretary of State for Scotland;

- • the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland; and

- • the Secretary of State for Wales.

- • the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government;

10.1.13 The convention of ministerial responsibility is an essential means of ensuring that Government is responsible for its actions. A responsible Government is one that is both accountable and responsive to Parliament and to the electorate.

10.1.14 Under the UK constitution this is not secured by formal or legal rules but by convention. The convention of ministerial responsibility comprises two aspects: individual ministerial responsibility; and collective ministerial responsibility.

10.1.15 However, at the same time it should be noted that the convention is difficult to define with any degree of certainty.

10.1.16 Whilst the Cabinet is at the core of government and has extensive powers, the doctrine of collective responsibility is a reminder that Parliament remains sovereign and that the Cabinet must answer to Parliament for its actions and inactions.

10.1.17 The classic definition of the convention of collective ministerial responsibility is that of Lord Salisbury in 1878: ‘For all that passes in Cabinet every member of it who does not resign is absolutely and irretrievably responsible and has no right afterwards to say that he agreed in one case to a compromise, while in another he was persuaded by his colleagues.’

10.1.18 The convention is justified by the need for the Government to present a united front to maintain public confidence, hence the Government as a whole should resign if defeated in a vote of no confidence, for example.

10.1.19 There are two rules under the convention of collective ministerial responsibility:

- • under the unanimity rule, once agreement is reached in the Cabinet, all members are bound to speak in support of the decision in public, regardless of whether they agreed or were present; and

- • under the confidentiality rule, all formal records of Cabinet meetings are protected from immediate disclosure and are released after a normally lengthy period of time (previously 30 years), which will be 20 years when the reforms provided by the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 are fully in effect.

10.1.20 Non-official accounts, such as memoirs, are subject to the principle set out in Attorney-General v Jonathan Cape Ltd (1976), which tells us that the publication of confidential information from Cabinet meetings in ministerial memoirs is subject, upon challenge, to the application of a public interest test under the law of confidentiality.

10.1.21 Resignations on the basis of a breakdown in the ability of the Cabinet to maintain a united front can result in considerable embarrassment for the Government. For example, the resignation of Geoffrey Howe was considered extremely influential in ending Margaret Thatcher’s Prime Ministership. Geoffrey Howe resigned over the Government’s policy on the issue of European Community (now European Union) membership.

10.1.22 In practice, the above rules should operate to protect a Minister under attack for a policy, decision etc. because their colleagues should help defend them. However, this may not be effective if the media is determined to pursue the matter and/or the Minister loses the support of the PM, which could force his or her resignation.

10.1.23 The convention is flexible and can be relaxed by the PM where in extreme circumstances agreement cannot be reached. For example, in 1975 the PM, Harold Wilson, waived the convention in respect of the UK’s continued membership of the then European Economic Community prior to a referendum.

10.1.24 This convention places Ministers in a position of having to answer for the work of their departments. The doctrine is identified with the Carltona principle (Carltona Ltd v Works Commissioners (1943)), which provides that a decision taken by a junior/subordinate official is regarded as being the decision of the Minister in charge of the department and he or she must answer for it in Parliament.

10.2 Ministerial responsibility and accountability, and a Ministerial Code

10.2.1 The modern basis for ministerial responsibility is now found in the Ministerial Code. This states that:

- • Ministers have a duty to Parliament to account for the policies, decisions and actions of their departments;

- • Ministers must give accurate and truthful information and correct errors at the earliest opportunity. Ministers that knowingly mislead are expected to offer their resignation to the PM;

- • Ministers should be as open as possible with Parliament, refusing to disclose information only when not in the public interest;

- • Ministers should require civil servants who give evidence on their behalf to a Parliamentary Committee under their direction to be as helpful as possible in providing accurate, truthful and full information; and

- • Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or appears to arise, between their public duties and their private interests.

10.2.2 In July 2011 the following addition to the Ministerial Code (2010) was approved by the Prime Minister, David Cameron:

‘The Government will be open about its links with the media. All meetings with newspaper and other media proprietors, editors and senior executives will be published quarterly regardless of the purpose of the meeting.’

10.2.3 This latest amendment to the expectations placed on Government Ministers by the Code is a move to highlight the need for accountability for ministerial involvement with particular sections of the news media, in particular, who may be swayed or biased toward particular coverage of ministerial policy, for example.

10.2.4 However, the Code has no legal force and there is no independent method of enforcing it. Instead the Code states that Ministers remain in office only as long as they have the confidence of the PM. It is therefore the PM that is ‘the ultimate judge of the standards of behaviour expected of a Minister and the appropriate consequences of a breach of those standards’.

10.2.5 It appears that, in the case of responsibility for departmental mal-administration or mismanagement, there are no clear rules on when a Minister should resign but three influential factors: whether they have the support of the Prime Minister; whether they have the support of their political Party; and whether they have any support in the media for their continuation in their post.

10.2.6 There are no provisions requiring Ministers to hold particular qualifications or a formal vetting process to identify their appropriateness to hold public office; appointment is purely at the discretion of the PM.

10.2.7 Personal conduct may lead to resignation, and indeed seemingly more so than in cases where there is acceptance of departmental responsibility.

10.2.8 The Ministerial Code provides that Ministers must scrupulously avoid any danger of an actual or apparent conflict of interest between their ministerial position and their private financial interests.

10.2.9 The Code no longer requires Ministers to resign any directorships they hold on assuming office, although if a Minister does have a financial interest he or she must not be involved in any decision-making relating to it.

10.3 Local authorities

10.3.1 Local government, carried out in the United Kingdom by bodies often known collectively as local authorities, is the creation of Parliament – specifically, certain Acts of Parliament.

10.3.2 Local government is the responsible layer of government for huge swathes of State operation in the social care, town planning, commercial licensing, development and environment, local transport and many education functions.

10.3.3 The Local Government Act 2000, the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 and the Localism Act 2011 between them have created a series of newer potential structures than the older county- or district-level authorities under the Local Government Act 1972, which were built around locally elected ward councillors, each representing a specific local area.

10.3.5 These newer arrangements now include the possibility of a local authority being governed, according to Elliott and Thomas, in one of four distinct ways (in England):

- • Firstly, an indirectly elected leader of a council body is chosen by the councillors whose Party has the most number of seats in the council governing that particular local authority. The leader of the council then appoints a cabinet around them to help them manage the affairs of the local authority, creating a council executive. The cabinet is challenged when necessary by ‘overview and scrutiny’ committees, modelled on parliamentary committees, and as such are comprised by ‘backbench’ councillors who are not part of the council cabinet.

- • Secondly, there is the possibility of a local authority being headed by a mayor, who is directly elected by the local voters, who also still vote on the particular councillors to represent their wards. Here, the mayor selects the cabinet to take the lead on governance of the local authority – again creating a council-level executive. Under the Local Government Act 2000 as amended there must be a local referendum to legitimise the switch to this model of local authority government.

- • Thirdly, councils can still be arranged along committee lines, with a nominal leader selected by ward councillors from amongst their own number, according to the dominant Party after a local election – but where there is no cabinet, only committees, which are meant to represent the political hue of all the councillors as a whole. This system means that, in theory, one highly successful Party following an election does not entirely dominate all of council business.

- • Fourthly, and finally, central Government can again, when requested by a local authority itself, stipulate some other kind of system that may be a fusion of elements of any or all of the above models, using powers again under the Local Government Act 2000.

10.3.6 Powers and responsibilities afforded to local authorities as public bodies with oversight in a particular area can be allotted and delegated internally, within the local authority itself, to an array of committees, subcommittees and officers, under section 101 of the Local Government Act 1972.

10.3.8 Ultimately, while local authorities often have enormous responsibilities in co-coordinating social care in the community, under the Care Act 2014 and other pieces of legislation, and child protection and other social work roles under the Children Act 1989, for example, their budgetary allocations, and their ability to levy local funds in the form of council tax, are all central-Government controlled.

10.3.9 The powers of local authorities have been nominally expanded under provisions of the Localism Act 2011, which provides local authorities with a ‘general power of competence’. The ‘plain English guide’ to the 2011 Act, produced by the Department of Communities and Local Government (in 2011), explains that:

‘Instead of being able to act only where the law says they can, local authorities will be freed to do anything – provided they do not break other laws… The new, general power gives councils more freedom to work together with others in new ways to drive down costs… The general power of competence does not remove any duties from local authorities – just like individuals they will continue to need to comply with duties placed on them. The Act does, however, give the Secretary of State the power to remove unnecessary restrictions and limitations where there is a good case to do so, subject to safeguards designed to protect vital services.’

10.3.10 It is vital to note, however, as Elliott and Thomas have observed, that ‘where councils have specified, restricted powers to do things, the general power cannot be used to circumvent such restrictions’.

10.3.11 In May 2015, following its success in the General Election that month, the Conservative Government announced plans for a Cities Devolution Bill, which would create a system of regional government on an unprecedented scale for the UK constitution. City regions, as centres of local government based in larger cities, with various towns around them included in that region, would be the recipients of much greater taxation, spending and borrowing powers – significantly reducing the control of the central, Westminster Government over the priorities and strategies for developing local or regional economies.

10.4 Police structures

10.4.1 It may be that many elements of the course you are studying in the areas of constitutional law and/or administrative law will have a focus on the roles, powers and legal duties of the police (if indeed you are studying a particular course). As such it is useful to highlight basic policing structures in the United Kingdom today.

10.4.2 England and Wales between them are served by 43 separate police bodies at the time of writing in May 2015, whilst Police Scotland and the Police Service of Northern Ireland carry out policing functions in Scotland and Northern Ireland respectively.

10.4.3 Complaints about the police and policing operations can be made by members of the public to the Independent Police Complaints Commission, if it cannot be fairly or finally addressed by the local police force complaints procedure.

10.4.4 Police standards are investigated and upheld, in theory, by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary – while police training and policy development is monitored and promulgated by the national-level College of Policing.

10.4.5 Importantly, while the Home Office and the relevant Government Minister, the Secretary of State for the Home Department (the Home Secretary), have a large role in developing and setting police practices and a policy and funding agenda for policing on a national level, at the regional level, the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 has created the role of a Police and Crime Commissioner for every police body.

10.4.6 The office of Police and Crime Commissioner is designed to hold to account each force-level Chief Constable, in whose person legal authority for particular operational policing decisions and practices often rests (and who will be the defendant in much judicial review litigation connected to policing as a result). Police and Crime Commissioners are supported in their aim to ensure and increase policing accountability and transparency by local Police and Crime Panels comprised of local councillors drawn from local authorities within the relevant force area (e.g. from local authorities in Sheffield, Rotherham, Barnsley and Doncaster in relation to South Yorkshire Police).

10.5 Different types of public body

10.5.1 For the purposes of much of your studies of public law, and particularly of administrative law, the pertinent issue in relation to defining public bodies is measuring whether they are amenable to judicial review of their actions and decisions.

10.5.2 To that end, broader concepts of what constitutes a public body for the purposes of judicial review are discussed at 12.4.

10.5.3 However, aside from central Government departments, headed by Government Ministers, local authorities and the police, there are three other main types of executive body.

10.5.4 As Elliott and Thomas have highlighted, these three categories are:

- Firstly: Non-ministerial departments such as Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) – structured in such a way to place them outside of ministerial control to try and enhance their political independence.

- Secondly: The extremely broad category of non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs). These, Elliott and Thomas note, include:

- • Bodies with executive powers (itself an enormously broad category, including the NHS Commissioning Board, known as ‘NHS England’, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the Environment Agency.

- • Advisory bodies created to advise the work of Ministers and their central Government departments; for example, as Elliott and Thomas note, the Social Security Advisory Committee advises the Department of Work and Pensions and so the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.

- • Tribunals which determine individuals’ rights, obligations and entitlements in relation to the roles and responsibilities of central Government departments.

- • Independent monitoring boards – such as those that inspect the standards and conditions in UK prisons.

- • Bodies with executive powers (itself an enormously broad category, including the NHS Commissioning Board, known as ‘NHS England’, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the Environment Agency.

- Thirdly: Executive agencies, headed by chief executives. These are created to try and make Government more efficient and expert in certain areas – for example, the National Offender Management Service (known as ‘NOMS’) oversees the work of dozens of newly formed private probation companies which win contracts from the Ministry of Justice to supervise and rehabilitate criminal offenders in the community.

10.5.5 As Elliott and Thomas note, the term ‘quango’ has been coined to describe ‘quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations’ as a kind of catch-all term for a range of types of public bodies that fall outside of clear central Government. The Public Bodies Act 2011, as Elliott and Thomas describe it, enables Minsters to abolish and merge public bodies using secondary legislation. But the ‘bonfire of the quangos’, which the Coalition Government sought in order to try to reduce costs of government across what it perceived as a bloated range of executive agencies. But the ‘bonfire’, as the press termed it, has so far only ‘smouldered’, as Tonkiss and Dommett have observed, and claims of overall costs saved are doubtful, as the work of abolished quangos has often needed to be re-assigned to re-structured, continuing Government bodies.