THE CONSTITUTIONAL ROLE AND CONFIGURATION OF JUDICIAL REVIEW

12

The constitutional role and configuration of judicial review

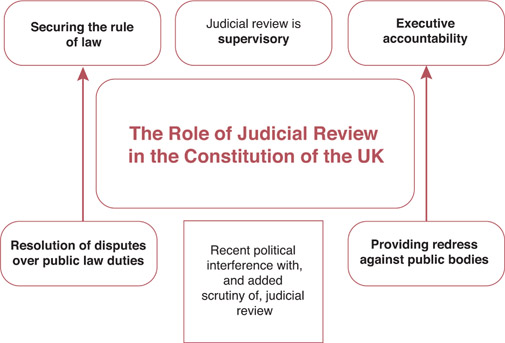

12.1 Defining the role of judicial review

12.1.1 Judicial review is the process whereby the judiciary examines the legality of the actions of the executive. Hence it represents the means by which the courts may control the exercise of governmental power.

12.1.2 Judicial review is closely aligned with securing the rule of law.

12.1.3 For example, Lord Hoffmann in R (Alconbury) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions (2001) described the significance of judicial review in terms of the constitution in the following terms: ‘The principles of judicial review give effect to the rule of law. They ensure that administrative decisions will be taken rationally in accordance with a fair procedure and within the powers conferred by Parliament.’

12.1.5 Judicial review is not an appeals process. In finding that a public body has exceeded its lawful authority, the court will not inquire into the subjective correctness of the decision, but only into the process by which the decision was reached. Unlike in an appeal, the court will therefore not substitute its own assessment of the merits.

12.1.6 The process of judicial review is therefore procedural in nature and determines whether a public body has acted within its powers (intra vires) or outside of its powers (ultra vires). If a body is determined to have acted intra vires its decision is not open to challenge under the process of judicial review.

12.1.7 Judicial review can consequently be described as a supervisory, rather than an appellate, jurisdiction.

12.1.8 Judicial review cannot be used for private law matters (see below). Where the matter is one of public law, judicial review must be used: O’Reilly v Mackman (1983). This is known as the ‘exclusivity principle’. However, where there is a combination of private and public law matters, the courts may be willing to generate exceptions to the exclusivity principle: see, for example, Roy v Kensington and Chelsea Family Practitioner Committee (1992); Mercury Communications Ltd v Director-General of Telecommunications (1996); and Clark v University of Lincolnshire and Humberside (2000).

12.1.9 As a matter of procedure in judicial review, cases are brought by the Crown on behalf of the applicant against a defendant public body.

12.2 A (problematic) growth in judicial review, or scrutiny of the Government we can be proud of?

12.2.1 In December 2012, the Ministry of Justice published a public consultation paper (‘Judicial Review: Proposals for reform’) which set out the argument that there had ‘been a significant growth in the use of Judicial Review to challenge decisions of public authorities, in particular over the last decade’. ‘In 1974’, claimed the Ministry of Justice, ‘there were 160 applications for Judicial Review, but by 2000 this had risen to nearly 4,250, and by 2011 had reached over 11,000.’

12.2.3 Two key suggestions by the Ministry of Justice were that time limits to bring an application for judicial review should be enforced more strictly, and that the required permission of the High Court to proceed to a judicial review hearing should be harder to obtain (see Chapter 13).

12.2.4 Legal academics Varda Bondy and Maurice Sunkin have challenged the use of bare statistics, such as the ones mentioned above, to argue that too many judicial review applications are being made against Government bodies.

12.2.5 Bondy and Sunkin have argued that ‘there has been little change in the volume of JR [judicial review] claims over the last 10 years or so’. ‘Since the mid 1990s’, they note, ‘the volume of non-immigration/asylum JRs has remained fairly stable at just over the 2,000 per annum mark’, highlighting that immigration and asylum law claims are responsible for the largest proportion of the growth in judicial review applications to the stated level observed by the Ministry of Justice at more than 11,000 per year by 2011.

12.2.6 But immigration and asylum law claims are now dealt with more efficiently, claimed Sunkin and Bondy under the newly established First-tier Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) (see Chapter 11), which the two legal academics hoped, from 2013 onwards, would perhaps ‘reduce significantly the volume of JRs in the Administrative Court [part of the High Court]’.

12.2.7 Sunkin and Bondy concluded as a result that (in early 2013 at least) it was potentially ‘misleading [of the Ministry of Justice] to rely on data relating to immigration/asylum JRs in order to justify reforms to the JR system as a whole’.

12.3 Judicial review and the Human Rights Act 1998

12.3.1 The Human Rights Act 1998 has had a significant impact on judicial review. Public bodies have a legal duty to act in accordance with Convention rights; failure to do so may result in judicial review proceedings.

- • the interpretation of a public body (and therefore which bodies are ‘amenable’ or subject to judicial review of their actions or decisions; and

- • the standing or ‘sufficient interest’ required to apply for judicial review.

These aspects will be discussed further below.

12.3.3 In addition, judicial review on human rights claims may result in a ‘declaration of incompatibility’, which could result in reform of the law (see Chapter 7 and Chapter 16).

12.3.4 Human rights-based review of actions or decisions by public bodies is often something that supplements pre-existing common law-based judicial review approaches. For example, the Human Rights Act 1998 also supplements the traditional judicial review requirements of natural justice by incorporating Article 6 of the ECHR in respect of the right to a fair trial.

12.4 Defining public bodies: amenability to judicial review

12.4.1 Judicial review is only available to challenge decisions made by public bodies. If the body is a private body, private law must be used.

12.4.2 There is no single test to identify a public body and the courts will examine a number of factors.

12.4.3 If a body is set up under statute or by delegated legislation then the source of its power means it is a public body and subject to judicial review.

12.4.4 However, where the matter is unclear, the courts should examine the ‘nature of the power’ being exercised. In R v City Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, ex parte Datafin Ltd (1987) it was held that if the body is exercising public law functions or if the exercise of its functions has public law consequences, it may be a public body and subject to judicial review.

12.4.5 Conversely, a body holding extensive regulatory powers may be concluded to be a private body, on the basis that such powers are based exclusively on contract or some other agreement to submit to their jurisdiction, for example, disciplinary powers exercised by sporting or professional bodies: R v Jockey Club, ex parte Aga Khan (1993) and R v Football Association, ex parte Football League (1993).

12.4.6 Under the Human Rights Act 1998 challenge through the process of judicial review can be made against decisions of public authorities, defined under section 6 to include courts and tribunals and ‘any person whose functions are functions of a public nature’. However, definition of a public authority within the context of the Human Rights Act has been narrowly interpreted (see e.g. R (Julian West) v Lloyd’s of London (2004)). (See in particular the discussion of YL v Birmingham City Council (2007) in Chapter 7.)

12.4.7 To determine whether a body is a public authority reference can be made to the following factors (Aston Cantlow and Wilmcote with Billesley Parochial Church Council v Wallbank (2003)):

- • whether the body is publicly funded;

- • whether the body is exercising statutory powers;

- • whether the body is taking the place of central Government or local authorities; and

- • whether the body is providing a public service.

12.4.8 Sometimes a private body can be deemed to owe duties under section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998, because the courts themselves (since they are public bodies) have a duty proactively to protect the rights of individuals subject to the actions of private bodies. This is known as the horizontality principle: Campbell v Mirror Group Newspapers (2004).