THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMPANY

The constitution of the company

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the key documents making up the constitution of pre-2006 Act and post-2006 Act registered companies

Identify the key documents making up the constitution of pre-2006 Act and post-2006 Act registered companies

Explain the key respects in which a pre-2006 Act company’s constitution differs from that of a post-2006 Act company

Explain the key respects in which a pre-2006 Act company’s constitution differs from that of a post-2006 Act company

Understand the historical importance of the ultra vires doctrine and objects clauses

Understand the historical importance of the ultra vires doctrine and objects clauses

Appreciate the effect, enforceability and importance of shareholders’ agreements

Appreciate the effect, enforceability and importance of shareholders’ agreements

Understand the role and importance of a company’s articles of association

Understand the role and importance of a company’s articles of association

Understand the role and relevance of the model articles

Understand the role and relevance of the model articles

Identify matters typically dealt with in a company’s articles

Identify matters typically dealt with in a company’s articles

Understand the legal limitations on what may be included in articles

Understand the legal limitations on what may be included in articles

Appreciate that the articles are a statutory contract and identify the unique characteristics of that contract

Appreciate that the articles are a statutory contract and identify the unique characteristics of that contract

Understand the legal problems and limits associated with enforcement of provisions of a company’s articles

Understand the legal problems and limits associated with enforcement of provisions of a company’s articles

Identify the statutory provisions governing amendment of a company’s articles

Identify the statutory provisions governing amendment of a company’s articles

Discuss the court-developed restrictions on amendment of a company’s articles

Discuss the court-developed restrictions on amendment of a company’s articles

Explain when articles will be implied as terms in contracts and the reasons why this may be necessary

Explain when articles will be implied as terms in contracts and the reasons why this may be necessary

5.1 What is the constitution of a company?

No comprehensive legal definition of the constitution of a company exists and the partial definition in s 17 of the Companies Act 2006 is not particularly helpful. The constitution is the company’s governance system; the rules and principles prescribing how it is to function. This governance system is a combination of:

1. legal rules and principles found in statutes and case law (general company law); and

2. rules and principles adopted by members of the company contained in

the articles of association;

the articles of association;

special resolutions;

special resolutions;

‘any resolution or agreement agreed to by all the members … that, if not so agreed, would not have been effective for its purpose unless passed by a special resolution’ (s 29).

‘any resolution or agreement agreed to by all the members … that, if not so agreed, would not have been effective for its purpose unless passed by a special resolution’ (s 29).

Unfortunately, exactly which shareholder decisions and agreements fall into the final sub-bullet point is not clear. This is an important issue because all constitutional documents, decisions and agreements must be registered with the registrar of companies, are available for public scrutiny (s 30) and must be sent to a member on request (s 32) with criminal liability for the company and every officer in default arising in the event of non-compliance. Some shareholders’ agreements fall within s 29 and therefore must be registered and some do not. Shareholders’ agreements are discussed at section 5.6.

For the purposes of supplying members with copies, the meaning of constitutional documents is extended to include a current statement of capital (or, in the case of a company limited by guarantee, the statement of guarantee), and the current (as well as any past) certificate of incorporation (s 32).

Today, the most important constitutional document of a company is its articles of association. The articles may or may not be supplemented by a shareholders’ agreement. Before focusing on the articles (at sections 5.3–5.5), and considering shareholders’ agreements (at section 5.6), it is helpful to consider the background to the Companies Act 2006 regime, thereby enabling you to understand the position of companies registered under an earlier companies act, and, in particular, the effect the 2006 Act has had on the constitutions of those companies. Additionally, many company law cases that are of continued relevance under the 2006 Act are difficult to understand without a basic understanding of the concepts of the objects and capacity of a company and the doctrine of ultra vires.

memorandum of association

The document which under predecessor companies acts set out the basic details of a company: name, place of incorporation, objects, liability of the members and authorised share capital but under the Companies Act 2006 is a shorter document containing the names of the initial subscribers for shares and their agreement to form a company

5.2 The objects and capacity of a company

5.2.1 Pre-Companies Act 2006 companies

Old-style memoranda of association

The objects and capacity of a pre-Companies Act 2006 company are rooted in its memorandum of association which makes it important to consider the role and content of an ‘old-style’ memorandum of association. Until 1 October 2009, each company had an old-style memorandum which contained the fundamental information listed below. Provisions of a memorandum could only be amended in limited circumstances following specified procedures.

An old-style memorandum could be used to entrench one or more provisions of a company’s constitution. Members could remove one or more provisions completely from the statutory power to amend, or render one or more provisions subject to a more restrictive amendment procedure than the statutory requirements. This was achieved by placing the relevant provision in the memorandum and stating either that it could not be amended, or, that it could be amended only if the specified procedure was gone through.

The mandatory provisions of an old-style memorandum of a company limited by shares (Companies Act 1985, s 2) were:

the company name;

the company name;

if the company was to be registered as a public company, this fact had to be stated;

if the company was to be registered as a public company, this fact had to be stated;

whether the registered office was to be in England, Wales or Scotland.

whether the registered office was to be in England, Wales or Scotland.

the company’s objects;

the company’s objects;

that the liability of the members was limited;

that the liability of the members was limited;

the share capital and how it was divided into shares of fixed amount;

the share capital and how it was divided into shares of fixed amount;

the names and addresses of each of the subscribers (the first members of the company) and the number of shares each agreed to acquire on registration.

the names and addresses of each of the subscribers (the first members of the company) and the number of shares each agreed to acquire on registration.

Objects clause

The clause in an old-style memorandum of association which sets out the business(es) the company proposes to carry on. Under the Companies Act 2006, the objects clause of pre-2006 Act companies has become a provision of the articles of association. A company incorporated under the 2006 Act may but need not have an objects clause in its articles.

ultra vires

The expression used to refer to a transaction entered into by a company that is beyond its legal capacity (historically, outside the scope of its objects clause). In this strict sense, ultra vires has been abolished in relation to non-charitable registered companies. Sometimes used to refer to a transaction beyond the powers of the directors, which use is best avoided

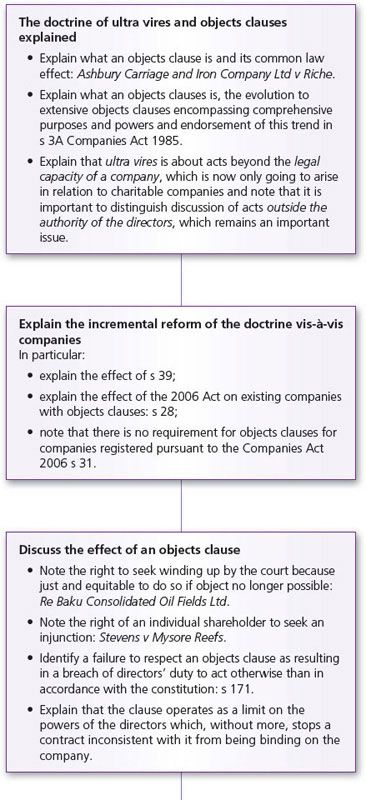

Objects, capacity and the ultra vires doctrine

Companies registered under a pre-2006 Act companies act (i.e. registered prior to 1 October 2009), had to be registered to pursue one or more ‘objects’ or types of business. A pre-2006 Act company’s object or objects were set out in the objects clause of the company’s old-style memorandum of association. Traditionally, the object of a company would be specific, such as ‘to operate a railway’.

The rationale for requiring a registered company to state its object or objects was to ensure that members and creditors of the company were clearly informed of the line of business the company had been formed to pursue. Before the landmark decision of the House of Lords in Ashbury Carriage and Iron Company Ltd v Riche (1875) LR 7 HL 653, the legal effect of stating objects in the memorandum of a registered company was not clear. It was unclear whether a registered company had the legal capacity of a natural person (essentially unlimited capacity), or a more limited legal capacity, namely the legal capacity to pursue its objects as stated in its memorandum of association and nothing more.

If the capacity of a registered company was limited, registered companies would be subject to the doctrine of ultra vires. Ultra vires is a doctrine of general application, not of relevance only to registered companies. It applies to all legal persons whose legal capacity to act is subject to limits, rendering acts outside the legal capacity of the person null and void.

In Ashbury Carriage the House of Lords decided that the doctrine of ultra vires did apply to registered companies, the legal capacity of which was limited to pursuit of the objects for which they were formed, as specified in the memorandum of association. This, the House of Lords stated, was the Legislature’s intention and the correct statutory interpretation of the Joint Stock Companies Act 1862.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Ashbury Carriage and Iron Company Ltd v Riche (1875) LR 7 HL 653 Ashbury Carriage and Iron Company Ltd was registered under the Joint Stock Companies Act 1862 with the objects, specified in its memorandum of association, of dealing in railway carriages and other railway plant and related lines of business which did not include the funding or construction of railway lines. The company entered into a contract to provide finance for the construction of a railway line in Belgium. When the company was sued to enforce the contract it argued that entry into the contract was ultra vires the company, the contract was void and that this remained the legal position even if the shareholders had authorised the contract or subsequently approved entry into it. Held: In favour of the company, per Lord Cairns: ‘In my opinion, beyond all doubt, on the true construction of the statute of 1862, creating this corporation, it appears that it was the intention of the Legislature, not implied, but actually expressed, that the corporation should not enter, having regard to its memorandum of association, into a contract of this description … every Court … is bound to treat that contract, entered into contrary to the enactment, I will not say as illegal, but as extra vires, and wholly null and void … I am clearly of opinion that this contract was entirely, as I have said, beyond the objects in the memorandum of association. If so, it was thereby placed beyond the powers of the company to make the contract. If so, my Lords, it is not a question whether the contract ever was ratified or was not ratified. It was a contract void from its beginning, it was void because the company could not make the contract.’ | |

Unfortunately, the term ultra vires is not always used in this strict sense and a great deal of confusion has arisen, particularly as a result of the term being used to describe a situation where, although the company has the legal capacity to act in a certain way, either the organ of the company (the board of directors or the shareholders) purporting to exercise a power does not have that power, or the particular individual within the company who performs the act (often, although not necessarily, a director), does not have the authority to do so. These are not cases of ultra vires, but rather cases of ‘excess of powers’ in that the organ acts beyond its powers or the agent acts outside the scope of his authority. It is advisable to avoid using the term ultra vires when the issue is excess of powers.

Very early in the history of the registered company, objects clauses began to be drafted to provide for a company to pursue more than one object or a range of objects. It became increasingly popular for specific objects in objects clauses to be followed by generic wording such as the right ‘to carry on any trade or business whatsoever which can, in the opinion of the board of directors, be advantageously carried on by the company in connection with or as ancillary to any of the above business or the general businesses of the company’ (language accepted as a valid object by the Court of Appeal in Bell Houses Ltd v City Wall Properties Ltd [1966] 2 QB 656).

The practice of drafting the objects of a company very broadly rendered the strict ultra vires doctrine of little practical relevance to most companies as almost any conceivable act would fall within the broadly stated objects. Even where ultra vires remained relevant to a given company, the effect of a company acting outside its capacity was altered by statute when the First European Company Law Directive was implemented in the UK (by s 9(1) of the European Communities Act 1972). Rather than protecting company members, this Directive focused on protecting those who traded with companies. At common law, if a third party contracted with a company and entry into the contract turned out to be outside the capacity of the company and therefore ultra vires, the legal right of the company to walk away (because the contract was null and void) protected the shareholders from the board of directors using company assets to pursue goals outside the line of business shareholders understood to be the object of the company when they invested in the company. This preserved the expectations of shareholders but left the third party’s expectations defeated as he was unable to enforce the contract.

In contrast, the Directive focused on protecting the third party dealing with the company. UK implementation of the Directive was, however, half-hearted. It provided that in favour of a person dealing in good faith with a company, any transaction decided upon by the directors was deemed to be within the capacity of the company. This left the ultra vires doctrine to operate in a number of situations, such as where the third party did not act in good faith. It also allowed a third party seeking to avoid a contract to invoke the ultra vires doctrine as the statute deemed the contract to be within the capacity of the company only in favour of a person dealing with the company and not in favour of the company. The company could not rely on the statutory provision.

SECTION

‘The validity of an act done by a company shall not be called into question on the ground of lack of capacity by reason of anything in the company’s [memorandum*] [constitution**].’

* Companies Act 1985; ** Companies Act 2006

Section 35 did not abolish the ultra vires doctrine completely. Traces of it remained and it is often said that it was abolished only in relation to outsiders. Companies still had to have objects clauses in their memoranda and the ultra vires doctrine was preserved insofar as it had implications for the rights of members in relation to the company and company insiders, the directors in particular. What remained was referred to as the ‘insider dimension’ of the ultra vires doctrine.

The remnants (or ‘insider dimension’) of the ultra vires doctrine were watered down even further by the Companies Act 2006 and, arguably, were wholly removed. Nowadays, not only does a (non-charitable) company have unlimited legal capacity as a result of what is now s 39 (above), but, due to the operation of s 28 (below), the legal effect of an objects clause has changed. All that now arguably remains of the ultra vires doctrine is the ability of an individual shareholder to obtain an injunction to restrain the doing of any act outside the objects of the company, the existence of which rule of law is referred to in s 40(4). This right, confined to the period before any legal obligations have been incurred by the company (s 40(4)), is arguably simply an example of the right of a shareholder to enforce the articles of association (see section 5.3).

The right of the company to sue any director who causes the company to engage in activity outside its objects is sometimes cited as a remaining aspect of the ultra vires doctrine but it is more helpfully portrayed as the right of the company to sue for breach of the directors’ duty, now set out in s 171(a), to act in accordance with the company’s constitution. The legal effects of restrictions on a company’s objects are considered more fully in the following section.

Note that special rules relating to ultra vires exist for charitable companies. The ultra vires doctrine has not been abolished in relation to charitable companies (s 42).

Impact of the 2006 Act on the constitution of pre-2006 Act companies

Every pre-2006 Act company once had, and most will continue to have an old-style memorandum registered with the registrar of companies as there is no obligation to take any action to change this situation. However, s 28 of the Companies Act 2006 fundamentally changes the effect of that document and the provisions contained in it.

‘s 28(1) Provisions that immediately before the commencement of this Part were contained in a company’s memorandum but are not provisions of the kind mentioned in section 8 (provisions of new-style memorandum) are to be treated after the commencement of this Part as provisions of the company’s articles.’

An objects clause in a company’s memorandum of association is now treated as a provision of the company’s articles. Objects clauses in the articles of a company will not limit the capacity of the company (s 39) and, with the exception of charities (as to which see s 42), and (possibly) the right referred to in s 40(4) (see above), the ultra vires doctrine will not be relevant to registered companies.

Objects clauses will, however, remain relevant but for different legal reasons. Being deemed to be provisions of the articles:

1. They will operate as a limitation on the authority of the board of directors to bind the company (although the common law position on this is significantly altered by ss 40 and 41 in order to protect third parties, see Chapter 10).

2. They will operate as a provision of the company’s constitution, and

a director owes the company a duty to act in accordance with the company’s constitution (s 171);

a director owes the company a duty to act in accordance with the company’s constitution (s 171);

a shareholder can apply for an injunction to prevent a company from acting outside its constitution, that is, beyond its restricted objects (s 40(4) and Stevens v Mysore Reefs (Kangundi) Mining Co Ltd [1902] 1 Ch 745).

a shareholder can apply for an injunction to prevent a company from acting outside its constitution, that is, beyond its restricted objects (s 40(4) and Stevens v Mysore Reefs (Kangundi) Mining Co Ltd [1902] 1 Ch 745).

3. Should the object no longer be pursuable or capable of achievement, the ‘substratum’ of the company may be regarded as gone which has been held to be a good ground for the court to order that the company be wound up under the Insolvency Act 1986, s 122(1)(g), on the basis that ‘the court is of the opinion that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up’.

5.2.2 Companies registered under the Companies Act 2006

The registration provisions of the Companies Act 2006 came into effect on 1 October 2009. Any company registered since that day is a UK company and this section, rather than section 5.2.1, is relevant.

New-style memoranda of association

A company registered under the Companies Act 2006 will have a new-style memorandum of association which is simply a prescribed-form document to be completed and filed with the registrar of companies at the time the company is registered. Unlike an old-style memorandum, a new-style memorandum will not be updated. It simply states (s 8), as a matter of record, that the subscribers:

wish to form a company under the Act;

wish to form a company under the Act;

agree to become members and, if the company is to have a share capital, to take at least one share each.

agree to become members and, if the company is to have a share capital, to take at least one share each.

Only one member is required for a company registered under the 2006 Act, whether it is a public or private company (s 7(1)). Single member private companies were permitted under the 1985 Act, but public companies were required to have a minimum of two members. This technical requirement was regularly satisfied by simply allotting one share to a person to hold the legal title as bare trustee for the other, main shareholder as beneficiary.

Objects, capacity and the ultra vires doctrine

As a result of s 39(1) (previously s 35, set out above), together with the change in the role of the memorandum of association, the ultra vires doctrine is no longer relevant to registered companies that are not charities. All non-charitable companies have the capacity of a natural person.

A company registered under the 2006 Act need not state the objects it is registered to pursue and, unless the articles specifically restrict them, the objects of the company are unrestricted (s 31(1)). Companies are not expected to choose to state objects in their articles. Some companies will, and the legal implications of an objects statement in the articles will be the same as the legal implications of an objects clause of a pre-2006 Act company that has been deemed to be a provision of its articles. (See section 5.2.1 where the impact of the 2006 Act on pre-2006 Act companies is addressed.)

KEY FACTS | |||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

articles of association

The regulations governing a company’s internal management including the rights of shareholders, the conduct of meetings and the appointment, removal and powers of directors. Separate model articles for public and private limited companies operate as the articles of a company to the extent that they have not been excluded or modified

5.3 The articles of association

5.3.1 What are the articles of association?

The articles of association contain the internal rules of the company. They state the organisational structure of the company, allocate powers to and between the organs of the company (the board of directors and the shareholders) and prescribe procedures for decision-making. They make up the most important constitutional document of a company registered under the Companies Act 2006 (due to the fundamental nature of the content of an old-style memorandum of association, before the Companies Act 2006 came into effect, it was regarded as the most important constitutional document of a pre-2006 Act company).

model articles

The default articles which, by operation of the Companies Act 2006, s 20, form part or all of the articles of a registered company on its formation to the extent that the incorporators do not register bespoke articles

5.3.2 Drafting articles and model articles

Although articles could be drafted from scratch, they rarely are. Company legislation has always contained model or default sets of articles and different sets of model articles exist for different types of companies. The model articles for companies limited by share capital registered under the Companies Act 1985 is known as ‘Table A’, and is relevant to both public and private companies. Under the 2006 Act, the name of the default articles has been changed to ‘model articles’ and the Model Articles for Private Companies Limited by Shares are different, containing a shorter and less formal set of rules (53 articles), from the Model Articles for Public Companies (86 articles) (see the Companies (Model Articles) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/3229)).

Model articles apply in the absence of alternative articles being filed on registration of the company (s 20(1)(a)). Past normal practice has been for part only of the relevant default articles to be adopted, supplemented by particular articles appropriate to the circumstances in which the company is being formed and the wishes of the prospective members. This is achieved by drafting a document that:

states ‘[T]he annexed version of the model articles shall be the articles of the company except as provided otherwise herein’;

states ‘[T]he annexed version of the model articles shall be the articles of the company except as provided otherwise herein’;

contains a list of individual articles from the model articles that do not apply;

contains a list of individual articles from the model articles that do not apply;

contains replacement and supplementary individual articles as required.

contains replacement and supplementary individual articles as required.

There is no reason to believe that this practice will not continue in the future. Note, however, the importance of stating clearly in the proposed articles those articles within the model articles that do not apply, as s 20(1)(b) provides that the relevant model articles will apply insofar as the proposed articles ‘do not exclude or modify the relevant model articles’.

5.3.3 Ascertaining the articles of association

On registration of the company, the initial articles are registered with the registrar of companies and are a document of public record. Articles can be amended, usually by special resolution, so it is always important to check that you have the most up to date version of the articles of a company. If you are reviewing a company search (documents about a company supplied from the public register), always check whether, since inception, there have been any amendments.

For older companies, always check which ‘Table A’ forms the basis of the articles as there have been different versions over time. Where a copy has not been attached, but simply referred to, it is sometimes necessary to dig out Table A from the companies act current at the time the company was incorporated.

5.3.4 Content of the articles of association

Range of issues typically covered by the articles

The following list is not comprehensive but gives a general indication of the principal matters covered by the articles of a company limited by share capital:

1. Limitation of liability:

limitation of the liability of shareholders.

limitation of the liability of shareholders.

2. Directors:

directors’ powers and responsibilities;

directors’ powers and responsibilities;

decision-making by directors;

decision-making by directors;

appointment of directors;

appointment of directors;

directors’ indemnity and insurance.

directors’ indemnity and insurance.

3. Decision-making by shareholders:

organisation of general meetings;

organisation of general meetings;

voting at general meetings;

voting at general meetings;

restrictions on members’ rights;

restrictions on members’ rights;

application of rules to class meetings.

application of rules to class meetings.

4. Shares and distributions:

issue of shares;

issue of shares;

interests in shares;

interests in shares;

share certificates and uncertificated shares;

share certificates and uncertificated shares;

liability of members;

liability of members;

partly paid shares;

partly paid shares;

transfer of shares;

transfer of shares;

distributions (dividends);

distributions (dividends);

capitalisation of profits.

capitalisation of profits.

This list is based on the Model Articles for Public Companies but most of the matters covered are also relevant to private companies limited by share capital.

Limits on the content of the articles

The content of the articles is a matter to be agreed upon by the original members of the company and may be changed from time to time as the company develops (see amendment of articles below). Basically, any matter may be included in the articles subject to the general principle that articles inconsistent with the law are void and unenforceable. Articles purporting to override certain statutory rights or powers have been held to be void and unenforceable. Two clear examples of this are Re Peveril Gold Mines Ltd [1898] 1 Ch 122 (CA) concerning an attempt to override the statutory right of shareholders to petition to wind up the company (Insolvency Act, s 124(1)), and Allen v Gold Reefs of West Africa Ltd [1900] 1 Ch 656 (CA) concerning an attempt to exclude the statutory right to amend the articles (s 21).

| Re Peveril Gold Mines Ltd [1898] 1 Ch 122 (CA) A provision in the articles of the company purported to limit the statutory right of a shareholder to petition the court to wind up the company under s 82 of the Companies Act 1862 (now s 124(1) of the Insolvency Act 1986). Held: The article was void. Per Chitty LJ: ‘In my opinion, this condition is annexed to the incorporation of a company with limited liability – that the company may be wound up under the circumstances, and at the instance of the persons, prescribed by the Act, and the articles of association cannot validly provide that the shareholders, who are entitled under s 82 to petition for a winding up, shall not do so except on certain conditions.’ | |

The power of a company to amend its articles by special resolution, currently found in s 21 of the Companies Act 2006 and considered below, has appeared in previous companies acts. The long established principle that a company cannot deprive itself of this statutory power by putting a provision to that effect in its articles, was confirmed by Lindley MR in the Court of Appeal in the leading case on amendment of the articles, Allen v Gold Reefs of West Africa Ltd [1900] 1 Ch 656 (CA):

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘[T]he company is empowered by the statute to alter the regulations contained in its articles from time to time by special resolution … and any regulation or article purporting to deprive the company of this power is invalid on the ground that it is contrary to the statute … The power thus conferred on companies to alter the regulations contained in their articles is limited only by the provisions contained in the statute.’ | |

The principle that a company cannot use its articles to exclude or limit the s 21 power to amend is subject to the statutory power, in s 22, to protect certain articles from amendment, i.e. to entrench certain articles. Only attempts to entrench articles that do not comply with s 22 will be null and void.

The principle that articles inconsistent with the law are void is simple to state but can be difficult to apply. It presupposes clarity as to which laws are mandatory and which may be opted out of, something not always clear in company law. Even if a particular statutory provision is asserted to be mandatory, on a number of occasions the courts have endorsed arrangements that in effect, if not in form, permit the statutory provision to be opted out of. Three cases exemplify this. Bushell v Faith [1969] 2 Ch 438 (HL) and Amalgamated Pest Control v McCarron [1995] 1 QdR 583 (Queensland Supreme Court, Australia) involve weighted voting rights in the context of the statutory right to remove directors by ordinary resolution and the passing of special resolutions. The third, Russell v Northern Bank Development Corporation [1992] 1 WLR 588 (HL), involved the impact of a voting agreement in a shareholders’ agreement and for this reason is discussed under shareholders’ agreements (at section 5.6).

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Bushell v Faith [1969] 2 Ch 438 (HL) A company had a share capital of 300 × £1 shares with 100 shares owned by each of Mr Faith, Mrs Bushell and Dr Bayne. An Article provided: ‘In the event of a resolution being proposed at any general meeting of the company for the removal from office of any director, any shares held by that director shall on a poll in respect of such resolution carry the right to three votes per share.’ An attempt was made to remove Mr Faith by ordinary resolution of the shareholders, relying on what is now s 168 Companies Act 2006. Held: Mr Faith could insist on three votes per share in any resolution to remove him from office, the result being that he could always outvote the other two shareholders, even though they owned two-thirds of the shares and could carry any other ordinary resolution. | |

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘Any case where the articles prescribed that a director should be removable during his period of office only by a special resolution or an extraordinary resolution … is overridden by [the Companies Act s 168]. A simple majority of the votes will now suffice … It is now contended, however, that [s 168] does something more; namely that it provides in effect that when the ordinary resolution proposing the removal of the director is put to the meeting each member present shall have one vote per share … Why should this be? The section does not say so as it easily could … Parliament followed its practice of leaving to companies and their shareholders liberty to allocate voting rights as they please.’ Per Lord Donavon | |

Is s 168 a mandatory rule or not? It can be circumvented by the use of weighted voting rights which suggests that it is not. Note, however, that the Listing Rules forbid the circumventing of s 168 by provisions such as this in the articles. The rule for companies with listed shares is therefore different from the rule for other companies (whether private or public). For companies with listed shares, s 168 is a mandatory rule.

The reasoning in Bushell v Faith was followed in the case of Amalgamated Pest Control [1995] 1 QdR 583 (Queensland Supreme Court, Australia). There, the articles of association gave one member 26 per cent of the votes on any special resolution with the result that he could defeat any special resolution. The Queensland Supreme Court upheld this allocation of voting rights.

Although articles are a type of agreement between all of the shareholders of a company, they are a document of public record and subject to unique rules, including rules as to amendment and enforcement, which makes them a ‘sui generis’ arrangement. Because of this, shareholders often prefer to capture the agreement between them in a separate agreement, a ‘shareholders’ agreement’. Shareholders’ agreements often contain important arrangements that impact on the way a company is managed and may render the articles misleading if not read in conjunction with the shareholders’ agreement. Shareholders’ agreements are considered in section 5.6.

5.3.5 Effect of the articles of association

The articles as a statutory contract

Section 33(1) of the Companies Act 2006 makes it clear that a contract is created by the articles of association.

SECTION

‘The provisions of a company’s constitution bind the company and its members to the same extent as if there were covenants on the part of the company and of each member to observe those provisions.’