THE COMPANY AS A DISTINCT AND LEGAL PERSON

The company as a distinct and legal person

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the consequences of a company having a separate legal personality from its owners and managers

Understand the consequences of a company having a separate legal personality from its owners and managers

Understand the concept of the limited liability of shareholders

Understand the concept of the limited liability of shareholders

Analyse and distinguish

Analyse and distinguish

legal personality of a company

legal personality of a company

shareholder limited liability

shareholder limited liability

Identify key ways by which the operation of the separate legal personality doctrine is supplemented or curtailed

Identify key ways by which the operation of the separate legal personality doctrine is supplemented or curtailed

Apply self-help remedies to fact situations to work around the separate legal personality doctrine

Apply self-help remedies to fact situations to work around the separate legal personality doctrine

Understand the importance of the interface of agency, tort and trust law principles with the separate legal personality of a company

Understand the importance of the interface of agency, tort and trust law principles with the separate legal personality of a company

Understand the limited situations in which a court will ignore the separate legal personality of a company and the basis for doing so

Understand the limited situations in which a court will ignore the separate legal personality of a company and the basis for doing so

Understand how a court will approach interpretation of a statute to determine whether or not it requires a court to ignore the separate legal personality of a company

Understand how a court will approach interpretation of a statute to determine whether or not it requires a court to ignore the separate legal personality of a company

Be aware of examples of key statutory provisions supplementing the remedies available to those owed money by a company

Be aware of examples of key statutory provisions supplementing the remedies available to those owed money by a company

Consider fact situations and determine whether or not a claimant against a company may have a remedy against any other person

Consider fact situations and determine whether or not a claimant against a company may have a remedy against any other person

Critically assess the operation and effect of separate legal personality in the context of a corporate group

Critically assess the operation and effect of separate legal personality in the context of a corporate group

3.1 The registered company as a corporation

Section 15(1) of the Companies Act 2006 makes it clear that registered companies become incorporated and separate legal persons on registration.

‘On the registration of a company, the registrar of companies shall give a certificate that the company is incorporated.’

Section 16(2) of the Companies Act 2006 makes it clear who the members of a registered company are and that the members may vary over time.

SECTION

‘The subscribers to the memorandum, together with such other persons as may from time to time become members of the company, are a body corporate by the name stated in the certificate of incorporation.’

To understand the meaning of corporation, it is important to understand the concept of a legal person. A legal person is a being or entity with the capacity both to:

enjoy (by virtue of its existence), or acquire, enforceable legal rights or property; and

enjoy (by virtue of its existence), or acquire, enforceable legal rights or property; and

be (by virtue of its existence), or become subject to, enforceable legal obligations and liabilities.

be (by virtue of its existence), or become subject to, enforceable legal obligations and liabilities.

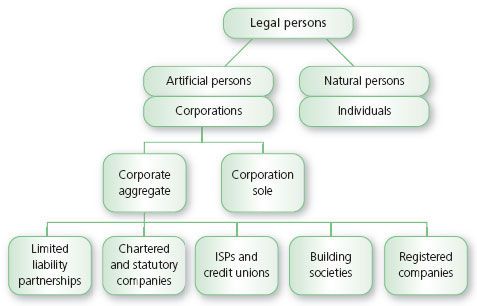

Legal persons fall into two categories:

natural persons (individuals, including you yourself); and

natural persons (individuals, including you yourself); and

artificial or juristic persons.

artificial or juristic persons.

The word ‘individual’ is used in this book to refer to a natural person. The term ‘person’ is used to cover both natural and artificial persons. All artificial or juristic persons are corporations. ‘Corporation’ and ‘to incorporate’ come from the Latin verb ‘corporare’ which means to furnish with a body or to infuse with substance. This is what the law does when it creates or recognises an artificial or juristic corporation: it furnishes an artificial construct with substance in the eyes of the law; with the ability to have legal rights and incur legal liabilities.

Corporations fall into two categories:

corporations sole;

corporations sole;

corporations aggregate.

corporations aggregate.

Corporations sole are limited by law to one member at any given time. Corporations sole are often attached as an incident of an office. Examples are the Crown and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Mayors are also generally corporations sole. The corporation sole is distinct in law from the individual who occupies the post at any point in time. The individual office-holder changes over time, but the corporation sole continues with no need to transfer any property or rights to the new incumbent. The individual’s acts in the capacity of the corporation are separate from the individual’s personal acts.

In the study of business organisations, we are not concerned with corporations sole; we are concerned with corporations aggregate. Corporations aggregate may (but need not) have more than one member at any given time. Statutory corporations, chartered corporations, registered companies, building societies, industrial and provident societies (co-operatives and community benefit societies), credit unions and limited liability partnerships are all examples of corporations aggregate. Figure 3.1 illustrates the classification of legal persons.

Figure 3.1 Types of legal persons.

incorporation

The process by which a legal entity, separate from its owners and managers, is formed

3.3 The consequences of incorporation/separate legal personality

In general terms, a company, because it is a corporation, is a person in law separate from any and all of the individuals involved in the company whether those individuals are its owners/shareholders, its managers/directors or are involved in some other way.

In general terms a company has the capacity to both:

enjoy (by virtue of its existence), or acquire, enforceable legal rights or property; and

enjoy (by virtue of its existence), or acquire, enforceable legal rights or property; and

be (by virtue of its existence), or become subject to, enforceable legal obligations and liabilities.

be (by virtue of its existence), or become subject to, enforceable legal obligations and liabilities.

In specific terms, like a natural person, a company:

can own property;

can own property;

can be a party to a contract;

can be a party to a contract;

can act tortiously;

can act tortiously;

can be a victim of tortious behaviour;

can be a victim of tortious behaviour;

can be a trustee;

can be a trustee;

can be a beneficiary of a trust;

can be a beneficiary of a trust;

can commit a crime;

can commit a crime;

can be the victim of a crime;

can be the victim of a crime;

has a nationality;

has a nationality;

has a domicile;

has a domicile;

has human rights;

has human rights;

has human rights responsibilities.

has human rights responsibilities.

Unlike a natural person, a company:

has perpetual existence until dissolved;

has perpetual existence until dissolved;

has owners;

has owners;

has no physical body or brain with which to act or think.

has no physical body or brain with which to act or think.

Although many of the legal rights and liabilities of a company parallel those of an individual, the scope and content of some of those legal rights and liabilities are not exactly the same as those of an individual. For example, although some human rights make sense in the context of an artificial person, others do not. Examples of human rights set out in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) exercisable by companies are:

the right to require a fair trial in the determination of its civil rights and obligations or any criminal charge against it (ECHR, Art 6) (see R (Alconbury Developments Ltd) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and Regions [2003] 2 AC 295);

the right to require a fair trial in the determination of its civil rights and obligations or any criminal charge against it (ECHR, Art 6) (see R (Alconbury Developments Ltd) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and Regions [2003] 2 AC 295);

freedom of expression (ECHR, Art 10) (see R (Northern Cyprus Tourist Centre Limited) v Transport for London [2005] UKHRR 1231);

freedom of expression (ECHR, Art 10) (see R (Northern Cyprus Tourist Centre Limited) v Transport for London [2005] UKHRR 1231);

prohibition of discrimination (ECHR, Art 14);

prohibition of discrimination (ECHR, Art 14);

the right to protection of company property (ECHR, Art 1 of Protocol 1) (see R (Infinis Plc) v Gas and Electricity Markets Authority [2013] EWCA Civ 70).

the right to protection of company property (ECHR, Art 1 of Protocol 1) (see R (Infinis Plc) v Gas and Electricity Markets Authority [2013] EWCA Civ 70).

The right of a company to assert a right of privacy pursuant to ECHR Art 8 was considered unfavourably but inconclusively by a strong Court of Appeal in R v Broadcasting Standards Commission [2001] QB 885. The impact the ECHR and the Human Rights Act 1998 from the perspective of protection of company property and profitability and the rights of companies is explored by Gearty and Phillips, and Aldred in articles referenced at the end of this chapter.

In relation to criminal liability, a number of criminal offences are specifically aimed at companies, particularly under the Companies Act 2006, and do not apply to individuals. Others have been drafted with companies as one class of accused in mind, for example, offences under the Health and Safety at Work Act etc. 1974. In relation to crime generally, many crimes were established with individuals in mind and the courts have wrestled to establish principles governing when an artificial entity will be considered to have the requisite mens rea and/or acted out the requisite actus reus, i.e. for our purposes, when acts and thoughts will be imputed to a company. The leading principle, derived from Lennard’s Carrying Co Ltd v Asiatic Petroleum Co Ltd [1915] AC 705 (HL) and developed by the courts is referred to as the ‘directing mind and will test’, the ‘identification theory’ or the ‘alter ego principle’. It was applied in the leading case of Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass [1972] AC 153 (HL), which involved Tesco advertising goods for sale at a price less than that at which it was actually offering them for sale, an offence under the Trade Descriptions Act 1968 at the time (since repealed and replaced by a different offence under the Consumer Protection Act 1987). The theory requires an individual to be ‘identified’ with the company for criminal liability to attach to the company. This arises where the individual is considered to be the ‘directing mind and will’ of the company. This attribution theory has resulted in difficult case law and the test has been called ‘dysfunctional’ (see Sullivan 1996).

The narrowness of the identification theory inhibited successful prosecution of companies following such national tragedies as the capsizing of the Herald of Free Enterprise (which caused 193 deaths), the Piper Alpha North Sea oil platform explosion (which caused 167 deaths) and the Paddington rail crash (which caused 31 deaths). Public outcry at the failure of the courts to deliver ‘justice’ resulted in the passage of the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 which took effect in April 2008 and reflects a systems-based principle of organisational behaviour rather than the individualistic principle developed by the courts. Guidance and an overview of the Act can be found on the Health and Safety Executive websites referenced at the end of this chapter. Under the Act, convicted companies face unlimited fines, remedial orders and publicity orders. The first six years of the Act saw only six prosecutions (guilty pleas were submitted in five) and although the Act was aimed at large companies, all prosecutions have been of small, private companies. Larger companies continue to be pursued under s 33 of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, with approximately 50 s 33 prosecutions of companies for fatal accidents in a similar period.

In the first prosecution under the 2007 Act, in 2011, Cotswold Geotechnical (Holdings) Ltd was convicted of corporate manslaughter following the death of an employee when a trial pit he was working in collapsed. The £385,000 fine, to be paid over ten years, resulted in the company being put into creditors’ voluntary liquidation. Overall, the maximum fine imposed under the 2007 Act has been £480,000 which is in contrast to a fine of £1.7 million imposed on Svitzer Marine Limited in 2013 under the 1974 Act.

The limits of the 2007 Act in relation to small companies was further demonstrated in relation to Mobile Sweepers (Reading) Limited, a company that, having ceased trading immediately after the death of one of its employees, was fined merely £12,000 (its entire value). Legal liability of the individuals involved is often more important to pursue and s 37 of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 provided the legal basis for fining Mobile Sweepers (Reading) Limited’s sole director £183,000, based on the company having committed offences under s 33 of the 1974 Act. The Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986 was also used to disqualify Mobile Sweepers (Reading) Limited’s sole director from being a company director or otherwise being involved in the management of any company for five years (the 1986 Act is considered in Chapter 13).

Difficulties implicit in imputing wrongful acts to a company are not confined to criminal law. The question of attribution arises in other areas of law, including tort and contract. In those areas, although the identification theory plays a part, attribution issues are largely dealt with by applying the principle of vicarious liability and agency law.

3.4 Limited liability: a concept distinct from separate legal personality

It follows inexorably from the separate identity of the company from its owners/shareholders and managers/directors that if a company incurs debts, those debts are the debts of the company, owed by the company to the lender/creditor. Without more, the debts of the company are not the debts of any other person. This means that not even the owners/shareholders of the company are liable to pay any sum owed by the company to the lender/creditor. Any legal action to recover the debt must be brought by the creditor naming the company as the defendant in the legal action. The owners/shareholders of the company are not parties to the contract pursuant to which the sum owed (the debt) is due to the creditor therefore action against them will fail.

what, if any, liability does an owner/shareholder of a company have to contribute money to the company to enable the company to pay its lenders/creditors?

what, if any, liability does an owner/shareholder of a company have to contribute money to the company to enable the company to pay its lenders/creditors?

The answer to this question depends upon whether the company in question is a limited or unlimited company.

limited company

A company the liability of whose members to contribute to the company to enable it to pay its debts is limited by shares or guarantee

3.4.1 Limited and unlimited companies

Owners of registered companies do not necessarily or always limit their liability to contribute sums to the company so that the company can pay the sums it, the company, owes to third parties: limited liability is an option available to incorporators of a registered company. As Figure 2.5 shows, it is possible to register a private company under the Companies Act 2006 with unlimited liability. Section 3(4) makes this clear.

SECTION

‘If there is no limit on the liability of its members, the company is an “unlimited company”.’

Unlimited companies are not popular vehicles for business organisations, but it is useful to focus on them here as they throw into sharp relief the difference between the concepts of separate legal personality and limited liability, concepts which are often treated as a single concept by students, resulting in misunderstanding. The liability of a shareholder to pay money into a company needs to be considered both when the company is trading, and when the company has ceased trading and is being wound up.

3.4.2 Shareholder payments to a company that is trading

A person can become a shareholder by acquiring shares in a company either from the company itself or from an existing shareholder. Most shares obtained from existing shareholders involve a stock exchange transaction. Most stock exchanges forbid trading in shares in relation to which any sum remains payable to the company by the shareholder. For this reason, this section will concentrate on shares acquired from the company and acquisition of shares from an existing shareholder will not be considered further.

Shares may be allotted and issued by a company and acquired by a shareholder on a fully paid-up, partly paid-up or nil-paid basis. Shares are fully paid-up when the shareholder pays to the company the whole of the share price (the amount due to the company) on allotment. As long as the company continues to trade, the company has no legal right to require a shareholder with fully paid-up shares to pay any further sum of money into the company. This is true, whether the company is a limited or unlimited company.

Where shares are obtained from a company on a partly paid or nil-paid basis the shareholder, at the time of allotment, does not pay to the company a part, or any (as the case may be), of the price payable for the shares. In such a case the company is entitled to call upon the shareholder to pay to the company any part, or the whole, of the amount of the share price as yet unpaid, at any time.

The power to make such calls on shareholders, to determine when and how much, is ordinarily given to the directors of the company who must exercise the power in accordance with their duties to the company. The common law rule that all shareholders must be treated equally when calls are made (see Preston v Grand Collier Dock Co (1840) 11 Sim 327), can now be contracted out of by including a provision in the articles of association of a company permitting shares to be allotted on the basis that different calls can be made on different shareholders at different times (see s 581(a) of the Companies Act 2006).

winding up

The liquidation of a company

3.4.3 Shareholder payments to a company that is being wound up

The law governing the obligation of a shareholder to contribute money to a company that has ceased trading and is being wound up is found in s 74 of the Insolvency Act 1986. When a company is being wound up, it is essential to distinguish limited and unlimited companies.

The starting point for both limited and unlimited companies is s 74(1) which provides that:

SECTION

‘When a company is wound up, every past and present member is liable to contribute to its assets to any amount sufficient for payment of its debts and liabilities.’

In the event of a company being wound up, a shareholder, without more, is required to contribute to the assets of a company sufficient to enable the company to pay its creditors and meet its other liabilities. Note, however, that even in relation to an unlimited company, a member is not liable to contribute to debts or liabilities incurred by the company after he or she has ceased to be a member and also is not liable to contribute anything at all if he or she has not been a member for a year or more at the time of the commencement of the winding up (see s 74(2)(a) and (b)).

Section 74 goes on to make specific provision for a company limited by shares. Section 74(2) (d) provides:

SECTION

‘[I]n the case of a company limited by shares, no contribution is required from any member exceeding the amount (if any) unpaid on the shares in respect of which he is liable as a present or past member.’

In relation to a company limited by shares, whether a public or a private company, which is being wound up, s 74(2)(d) of the Insolvency Act 1986 is the statutory basis on which the liability of shareholders to contribute to the company to enable it to pay its debts and other liabilities is limited. The limit is the amount (if any) unpaid on the shares. If that amount has been paid to the company, a shareholder is under no further obligation to contribute.

3.4.4 Justifications for limited liability

Shareholders of the first registered companies did not have limited liability. As outlined in Chapter 1, the debate as to the costs and benefits limited liability would bring were still being debated in 1844, when the first incorporation statute was enacted. Although the debate was soon won by those advocating the beneficial consequences of limiting the liability of shareholders, limited liability was initially introduced for large companies only, that is, companies with a minimum of 25 shareholders that met certain minimum share value and issued share capital requirements (see s 1 of the Limited Liability Act 1855). This restricted availability was relaxed the very next year by the Joint Stock Companies Act 1856.

The key benefits of limited liability are:

encouragement of investment by members of the public in companies;

encouragement of investment by members of the public in companies;

facilitation of the transferability of shares;

facilitation of the transferability of shares;

clarity and certainty as to the assets available to creditors of the company.

clarity and certainty as to the assets available to creditors of the company.

3.5 Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd

The most famous case illustrating the operation of the concept of the separate legal personality of a company is Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22 (HL). The case was hard fought, all the way to the House of Lords, by the liquidator on behalf of the unsecured creditors of a company that had become insolvent very soon after being registered under the Companies Act 1862. The case is important because it confirmed the ability of a sole trader to transfer his business into a registered company and thereby insulate himself from the liabilities of the business.

Before this case, the full significance of the ability to incorporate a limited liability company by registration was not appreciated. As the judgments at first instance and in the Court of Appeal indicate, as the nineteenth century was drawing to a close, it was not widely understood that sole trader owners of small businesses could use the Act to secure limited liability and insulate their personal property from business risks.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22 (HL) Mr Salomon owned and ran a profitable boot and shoe manufacturing business as a sole trader. He wished to run his business through a limited company which he achieved by registering a company and selling his business to that company. The statute governing company registrations at that time required seven subscribers to the memorandum of association, i.e. seven original members or shareholders. Mr Salomon satisfied this requirement by himself, his wife and his five grown-up children becoming subscribers (under the Companies Act 2006 only one subscriber or member is required). The initial nominal share capital of the company was £40,000. This was divided into 40,000 shares with a nominal value of £1 each. Seven £1 shares were issued, one being issued to each shareholder/member/subscriber which made the initial issued share capital of the company £7. The first directors were appointed by the shareholders and were Mr Salomon and his two eldest sons. The sale price of the business to the company was ‘the sanguine expectations of a fond owner’, rather than the market value of the business. In short, the business was sold to the company at an overvalue. In return for the business being transferred to the company, the £39,000 purchase price for the business was ‘paid’ by the company to Mr Salomon in the following way:

Secured creditors are entitled to be paid before the unsecured creditors of a company (see Chapter 15). The proceeds of sale of the company’s assets were insufficient even to pay the secured creditor, Mr Broderip, in full. In these unhappy circumstances, the liquidator brought an action against Mr Broderip and Mr Salomon alleging the loan notes issued by the company were fraudulent and invalid. The liquidator was successful at first instance and in the Court of Appeal but was appealed to the House of Lords. Held: Mr Salomon had done nothing wrong, was not liable for the debts of the company, and the loans between him and the company and Broderip and the company were valid. | |

3.5.1 The first instance and Court of Appeal decisions

The first instance judge in Salomon decided that fraud was not established on the facts of the case. He did, however, use agency principles to decide that the company was Mr Salomon’s agent and on that basis he ordered Mr Salomon, the principal, to indemnify the company, the agent, for the debts the company had incurred as his agent. The Court of Appeal rejected the first instance agency argument. Lindley LJ preferred to hold that the company was the trustee of Mr Salomon who was the beneficiary. Lindley LJ described the company as, ‘A trustee improperly brought into existence by him to enable him to do what the statute prohibits’, therefore, he held, the beneficiary (Mr Salomon) must indemnify the trustee, the company.

Lopes LJ regarded the family member/shareholders as ‘dummies’. What the Act required, he stated, were, ‘seven independent bona fide members, who had a mind and a will of their own’. According to Lopes LJ, ‘The transaction is a device to apply the machinery of the [1862 Act] to a state of things never contemplated by that Act – an ingenious device to obtain the protections of the Act, and in my judgment in a way inconsistent with and opposed to its policy and provisions.’ He ordered that the sale of the business to the company be set aside as a sale by Salomon to himself with none of the incidents of a sale, but being a fiction.

3.5.2 The House of Lords decision

In dismissing the claims of the liquidator, members of the House of Lords totally disagreed with the decisions at first instance and in the Court of Appeal which, they said, had misconceived the scope and effect of the 1862 Act. Lord MacNaghten’s judgment was particularly lucid:

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘[T]hough it may be that after incorporation the business is precisely the same as it was before, and the same persons are managers and the same hands receive the profits, the company is not in law the agent of the subscribers or trustee of them. Nor are the members liable, in any shape or form, except to the extent and in the manner provided by the Act.’ | |

Writing in 1944, Kahn-Freund commented:

QUOTATION

‘In this country as elsewhere company law has, to a large extent, changed its economic and social function. The privileges of incorporation or of limited liability were originally granted in order to enable a number of capitalists to embark upon risky adventures without shouldering the burden of personal liability … However, owing to the ease with which companies can be formed in this country, and owing to the rigidity with which the courts applied the corporate entity concept ever since the calamitous decision in Salomon v Salomon & Co Ltd, a single trader or a group of traders are almost tempted by the law to conduct their business in the form of a limited company, even where no particular business risk is involved, and where no outside capital is required …

The metaphysical separation between a man in his individual capacity and his capacity as a one-man-company can be used to defraud his creditors who are exposed to grave injury owing to the timidity of the Courts and of the Companies Act.’

O Kahn-Freund, ‘Some reflections on company law reform’ (1944) 7 MLR 54

The rigidity to which Kahn-Freund referred is clearly in evidence in the recent Supreme Court case of Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd [2013] 2 AC 415 (at 476).

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘Subject to very limited exceptions, most of which are statutory, a company is a legal entity distinct from its shareholders. It has rights and liabilities of its own which are distinct from those of its shareholders. Its property is its own, and not that of its shareholder. In Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22, the House of Lords held that these principles applied as much to a company that was wholly owned and controlled by one man as to any other company. … The separate personality and property of a company is sometimes described as a fiction, and in a sense it is. But the fiction is the whole foundation of English company and insolvency law.’ Lord Sumption | |

3.5.3 Separate legal personality and insurance

One area in particular in which difficulty arose as a result of the failure of businessmen to appreciate the ‘tyrannical sway’ the corporate entity metaphor holds over the courts is insurance of company property. In a triad of cases (Macaura (see below), General Accident v Midland Bank Ltd [1940] 2 KB 388 and Levinger v Licences etc Insurance Co (1936) 54 LL L Rep 68), insurance companies have avoided paying out under insurance contracts for which they have received premiums, based on the insured property being owned not by the party insuring it (the shareholder of the company), but, rather by the company itself.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Macaura v Northern Assurance Co [1925] AC 619 (HL) After selling his property (timber) to a company in return for shares, Macaura, the sole shareholder of Irish Canadian Sawmills Ltd, insured the timber against fire in his own name. The timber was destroyed by fire and Macaura claimed on the insurance policy. Held: The property belonged to the company, not to the shareholder. Even though the timber had been destroyed by an insured event, Macaura had no insurable interest in the timber as ‘he stood in no “legal or equitable relation” to it’ and so could not recover under the insurance policy. | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

3.6 Limits on the implications of incorporation/separate legal personality

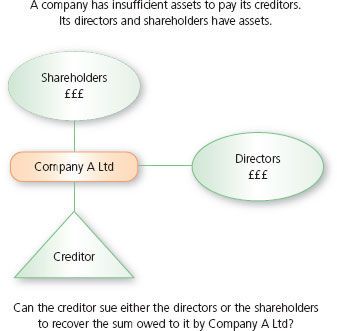

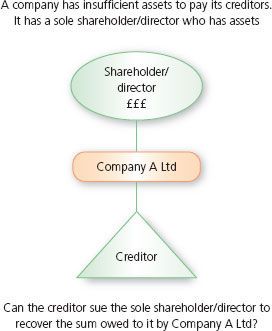

We have identified the main legal consequences of the separate legal personality of a company (see section 3.3). It is important to understand the ways in which these consequences may be supplemented or curtailed to provide a person with a legal remedy different from that dictated by a strict application of the separate legal personality doctrine, whether by self-help action, by a variety of legal arguments based on either statute or case law, or by a mixture of both. When exploring these actions and arguments, it is helpful to have in mind a number of typical scenarios involving legal claims against companies and those who have set them up.

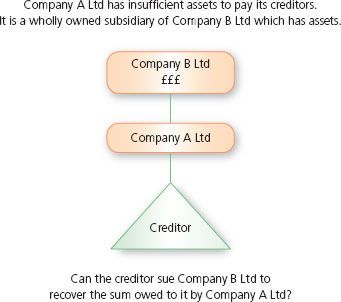

It follows from the separate legal personality of companies and the ability of a company to own property that one company can own shares in another company. This is the basis for the existence of corporate groups that can be, and are not uncommonly, made up of over 100 companies, all owned, ultimately, by one parent company. In the third typical scenario in Figure 3.4, Company B Ltd owns all of the shares in Company A Ltd. Company B Ltd is the parent company of Company A Ltd and Company A Ltd is a wholly owned subsidiary of Company B Ltd.

3.6.2 Self-help action to mitigate the consequences of incorporation

A person dealing with a company can often work around the main consequence of the company being a person separate from its shareholders, namely that its shareholders are not liable for the debts and obligations of the company, by putting appropriate contractual or agency arrangements in place. This behaviour is often called ‘self-help’ action.

Figure 3.2 Typical scenario 1.

Figure 3.3 Typical scenario 2.

Figure 3.4 Typical scenario 3.

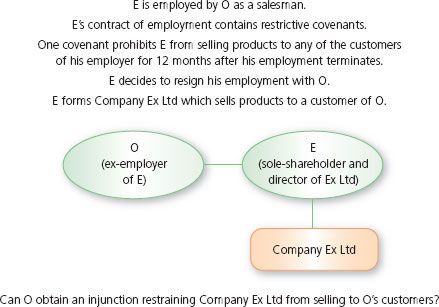

Figure 3.5 Using a company to avoid an existing legal obligation.

In each of Figures 3.2 to 3.4, the creditor could have insisted that the shareholder (or one or more of the shareholders) guarantee the obligations of Company A Ltd under any loan between the creditor and Company A Ltd. Such guarantees are very common in the context of corporate groups, when they are called ‘parent guarantees’. They are also very common in the context of sole member or closely held companies.

In Figure 3.5, O, the ex-employer, could protect itself by appropriate language in E’s contract of employment. The contractual clause containing the restrictive covenant could be drafted so that the restriction covered sales to O’s customers by E or any company owned or controlled by E. It would also be sensible to define control for the purposes of the covenant.

These are two illustrations of how contracts can be used to work around the consequences of incorporation. Agency is a particular type of contractual relationship. An agency relationship may be put in place between a company and its shareholder. A claimant often seeks to establish that a company is the agent of its shareholder so that the claimant has a claim against the principal (the shareholder) rather than the (insolvent) agent/company.

agent

A person with authority to alter the legal position of another person which other person is known as the principal

The sum of £9,000 was paid in cash (£8,000 of which, with no legal obligation to do so, Mr Salomon used to pay off debts of the business).

The sum of £9,000 was paid in cash (£8,000 of which, with no legal obligation to do so, Mr Salomon used to pay off debts of the business). A total of 20,000 shares of £1 each were issued to Mr Salomon, credited as fully paid-up shares (i.e. the shares were regarded as having been paid for by Mr Salomon, not in cash but ‘in kind’, by the transfer to the company of £20,000 pounds’ worth of the business).

A total of 20,000 shares of £1 each were issued to Mr Salomon, credited as fully paid-up shares (i.e. the shares were regarded as having been paid for by Mr Salomon, not in cash but ‘in kind’, by the transfer to the company of £20,000 pounds’ worth of the business). A £10,000 secured loan note, or, ‘debenture’ was issued to Mr Salomon recording that the company owed Mr Salomon £10,000 pounds secured by a charge over the company’s assets.

A £10,000 secured loan note, or, ‘debenture’ was issued to Mr Salomon recording that the company owed Mr Salomon £10,000 pounds secured by a charge over the company’s assets.