The Board of Appellate Review

The Board of Appellate Review

In reaching conclusions about the preponderance of evidence I think that the Board should take care not to be misled into simply weighing the quantity of evidence tending to prove intent as against the quantity of evidence tending to disprove it.

—Warren E. Hewitt, 1985

Between the years 1980 and 1996, the Board of Appellate Review reviewed 669 contested cases of expatriation. This number includes all appeals made regarding expatriation (594), motions for reconsideration for those appeals (52), and several cases regarding the renewal of passports and immigration (23). Here, I will present statistics on such matters as the number of cases each year, the grounds for the revocation of citizenship, and the outcome of the appeal. The limitation of such a report is that it misses out on the complexities and uniqueness of each deliberation. Each one of the persons who lost his or her citizenship and appealed to the board had unique circumstances, gave explanations for his or her deeds, and made verbal presentations, and members of the board made enormous efforts to capture these in their deliberations. For this reason, I also describe in depth several of the cases and present the different elements that persuaded the board members to affirm or reverse the administrative decision of expatriation. My aim is not to question any specific decision made by the board members but to identify the underlying assumptions of the board regarding the idea of citizenship, and more specifically the notion that citizenship ought not to be divided or multiple.

The Supreme Court in Vance v. Terrazas (1980) held that in order to take away citizenship, the government had to prove that the expatriating act was made with the intent to relinquish U.S. citizenship. Theoretically, this decision should have ended the decades of debates regarding the legitimacy of forced expatriation. The verdict maintained that only the citizen could determine whether to cease being American. It was the citizen’s intent, not only his or her disloyal or questionable act, which would be the benchmark for any expatriation decision. From a legal perspective, two major questions remained: “What is intent?” and “What acts or statements should be weighed in ascertaining intent?” The Board of Appellate Review was, in practice, the body that formulated the answers to these questions.1

The work of the Board of Appellate Review has been discussed in the past in several law journals.2 Here, I am able to introduce at least three new elements. First, while previous descriptions of the board’s actions were undertaken during the 1980s, I am able to analyze the changes in its deliberations and procedures after those dates and especially with respect to the transformations in the understanding of expatriation acts in the Department of State in 1990. Second, by quantifying all the appeals made to the Board of Appellate, I am better able to portray the recurrences and trends in affirming or reversing the Department of State’s expatriation decisions, as well as the backgrounds of the individuals who appealed. Lastly, I connect the debates in the board to larger perceptions of citizenship and belonging. That is, I reveal the political philosophies that underpinned the board’s legal conclusions.

The Board of Appellate Review’s Task

The Board of Appellate Review was set up in 1967 to hear appeals and evaluate decisions made by the State Department. The board had the jurisdiction to hear appeals on a variety of administrative decisions such as the cancellation of passports, contract disputes, and expatriation. However, most of the cases discussed were appeals regarding the revocation of U.S. citizenship. Between 1980 and 1996 the board heard 669 appeals of which the vast majority of cases (96 percent) were to decide whether performing a statutory act of expatriation was done with the intent to relinquish American citizenship. I have complete information on only 456 individuals plus 44 appeals for reconsideration of the decisions made by the Board of Appellate Review regarding expatriation. In most cases the affirmation to reverse the State Department’s original decision to revoke American citizenship was unanimous (440 cases). However, in a few cases (16), one of the three members insisted that the board should record his or her dissenting opinion. Proving intent was not always an easy task, and was not always agreed upon by all of the board’s members.

One of these instances was in the cases of Jeannette Elizabeth Mollenhauer and her husband, John Anthony Mollenhauer. Both were American citizens by birth. John served in the U.S. Army during the Second World War. In 1975, they decided to move to Canada, and six years later, they acquired Canadian citizenship. The record does not show how the American authorities found out about the naturalization in Canada, but once they did, they asked John and Elizabeth to complete a form regarding this act.

In question 13 the couple were asked if they knew that by obtaining naturalization in a foreign state they might lose U.S. citizenship. John replied “Yes—the United States does not permit dual citizenship.” In a later questionnaire for determining intent, John added that they had consulted with a U.S. embassy official in Winnipeg regarding the possible expatriation and understood it was necessary in order to obtain Canadian citizenship. On February 4, 1983, the consulate general at Winnipeg prepared a certificate of loss of nationality, which was approved a month later by the State Department, in the names of Jeannette Elizabeth Mollenhauer and John Anthony Mollenhauer. At the end of the year John and Elizabeth filed an appeal to the Board of Appellate Review.

The first stage of this drama illustrates the typical procedure that U.S. consulates around the world follow. First, consular officials must advise citizens and give information on the consequences that certain acts may have on their citizenship. This can happen before the expatriating acts were committed, or as in the case of the Mollenhauers, sometime afterward.

In 1967, when the Board of Appellate Review was established, there were thirteen statutory expatriating acts: having a subversive political stance; deserting in time of war (§349a9); departing the United States to avoid conscription in time of war (§349a10); obtaining benefits from a foreign country (§350); voting in a foreign election (§401e); establishing residence abroad (§352a2); obtaining naturalization in a foreign state (§349a1, previously §401a, and section 2 in the 1907 act); making an oath of allegiance to a foreign state (§349a2 and previously §401b); serving in a foreign army (§349a3 and §401c); serving in a foreign government (§349a4 and previously §401a); making a formal renunciation abroad (§349a5, previously §349a6 and §401f) or in the United States during war time (§349a7); and committing treason (§349a8). By 1994, the first seven grounds for expatriation were determined to be unconstitutional and were removed from the books. Since 1980, the consulates have informed citizens who committed one of the remaining expatriation acts about the importance of intent, and have allowed citizens to make a declaration of intent just after receiving a notice regarding a certificate of loss of nationality, in order to preserve their American citizenship.

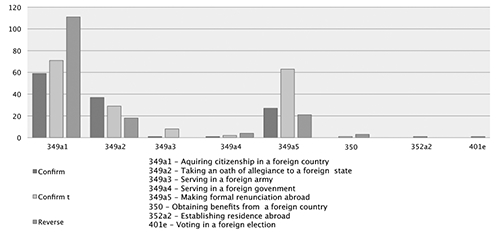

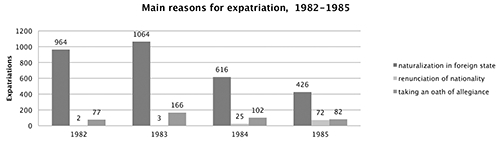

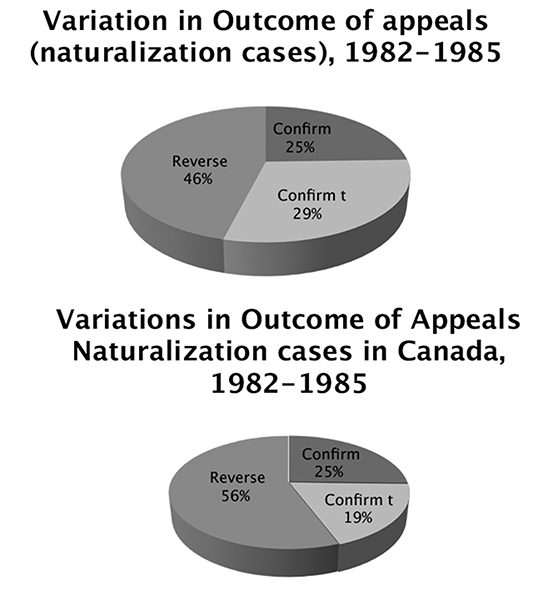

The contrast between descriptive data on the variation in the expatriation acts that were appealed (Figure 7.1) and the reasons for and numbers of expatriations (Figure 7.2) is quite revealing. In Figure 7.1, I describe the three possible outcomes—confirmation of the original decision, reversal of the original decision, and confirmation of the original decision when the board concluded that it is time-barred from ruling on the issue (marked as “confirmed t”). The three most common expatriation acts were acquiring citizenship in a foreign country (§349a1, previously §401a, and section 2 in the 1907 act); making a formal renunciation abroad (§349a5, previously §349a6 and §401f); and making an oath of allegiance to a foreign state (§349a2 and previously §401b). Those three grounds for expatriation were also the three main reasons for expatriation in all cases (Figure 7.2) in the years 1982–1985.3 Contrary to the notion that was ruled upon by the Supreme Court, voluntary renunciation of citizenship was not the only reason for the loss of citizenship. It was not even the main reason for the loss of citizenship. In fact, most citizens lost their citizenship without formally, voluntarily, or explicitly requesting to relinquish their American citizenship (either by acquiring another foreign citizenship or by making an oath to a foreign country). Although making a formal renunciation of citizenship is perceived as the ultimate indication for wanting not to be American anymore, more people demanded to keep their citizenship and appealed to the board after performing this act than people who had sworn an oath to foreign country and had lost their citizenship, but desired to retain American citizenship (see Figure 7.1). It was expected that the board would reverse some of the Department of State’s decisions to revoke citizenship after the American citizen acquired another foreign citizenship or swore an oath to a foreign country as it could not prove that the act was committed with the intent to relinquish U.S. citizenship. However, it is surprising that the board came to this conclusion in cases when the citizen had made an unambiguous formal request to cease to be American.

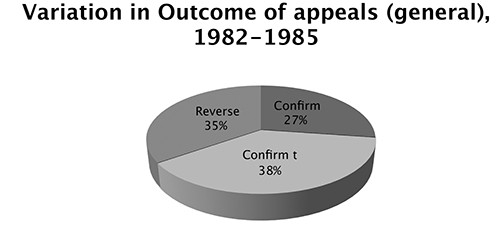

Also important is the fact that many of the appeals were rejected because they were time-barred so that the board did not have jurisdiction to rule in those cases. In general, in 35 percent of the appeals, the board agreed with the appellants’ request to retain their American citizenship and reversed their original loss of citizenship (see Figure 7.3).

Locating Intent

The consular office is legally bound to report all known acts of expatriation acts to the State Department. The officers can learn about these acts from the citizens themselves who come to seek advice or request services (such as renewing their American passport) or from the foreign government. In the case of the Mollenhauers, the record does not show how the consulate in Winnipeg learned about their naturalization, but it is suspected that they consulted an attorney who later approached the consulate-general.

After the citizen receives the administrative determination of loss of nationality, he or she can file an appeal in a timely and appropriate manner. Then the Board of Appellate Review needs to assess two issues: whether the State Department can prove that the expatriating act was performed voluntarily, and whether it can show that this act was done with the intent to relinquish United States citizenship.

Jeannette and John conceded that the expatriating act—namely, their naturalization in Canada—was done voluntarily. In September 1981, John was granted a certificate of Canadian citizenship. He explained that he felt living in Canada would improve his employment opportunities and stated that his intentions were “to participate in society as a normal citizen in Canada while I resided there.”4 Jeannette also acquired Canadian citizenship upon her own application on the same date. The Mollenhauers did not try to rebut the fact that the statutory act of expatriation was performed voluntarily and the board decided accordingly that the act was undertaken through exercising their free will. The next stage, to show that the Department of State had fulfilled its burden of proof by a preponderance of the evidence that in voluntarily obtaining naturalization in Canada the appellants had intended to relinquish their United States citizenship, was more difficult.

After reviewing their statements (such as their conversations with the consular officers), their written words (such as the questionnaire they filled in at the consulate), and their actions or failure to act (such as their applications for a U.S. passport and its use, connections with family in the United States, and the filing of U.S. States income tax returns), the board had to decide whether intent to relinquish U.S. citizenship was clearly established. The board’s majority (Alan G. James and J. Peter A. Bernhardt) concluded that there was nothing in the record to show that they had obtained a Canadian passport or that they held themselves solely as Canadian citizens. Therefore, the Department of State had not sustained its burden of proof, and thus James and Bernhardt reversed the department’s decision of loss of U.S. citizenship.

Warren E. Hewitt, who was the third member of the Board of Appellate Review at that time, did not agree with the majority opinion. In his dissenting opinion in the Mollenhauers case, he argued that “In reaching conclusions about the preponderance of evidence I think that the board should take care not to be misled into simply weighing the quantity of evidence tending to prove intent as against the quantity of evidence tending to disprove it. The critical judgment must be the probative force of the separate pieces of evidence that do exist.”5 That is, the board should look on both the acts and words of the citizen at the time he or she performed the expatriating act, and especially the relevant evidence that indicates intent. Hewitt placed more weight on the Mollenhauers explicit written statements at the time of expatriation that they had been fully aware that their American citizenship might be taken away and that they intended to reacquire this citizenship in the future. The written words were to be taken at face value, and there was no reason to look for nuances. Therefore, in this case, Hewitt was of the opinion that the board must affirm the Department of State’s certificate of loss of nationality.

On July 1985, the Department of State moved for reconsideration of cases of the board’s decision to reverse the original verdict of loss of nationality. About a quarter of the motions for reconsideration (10) were initiated by the state. All the other (44) were appeals from the individuals who did not agree with the board’s conclusion and believed it had overlooked or misread some of the evidence in their case. In the case of the Mollenhauers, the board agreed to reexamine the evidence but concluded that their original decision to reverse the department’s determination that the Mollenhauers had expatriated themselves when they obtained naturalization in Canada still stood.