Supreme Court Agenda Setting: Policy Uncertainty and Legal Considerations

Supreme Court Agenda Setting

Policy Uncertainty and Legal Considerations

On November 2, 1992, the National Organization for Women (NOW) requested that the U.S. Supreme Court exercise its discretionary agenda-setting powers and review the lower court’s decision in NOW v. Scheidler (No. 92–780). NOW asked the Court to apply the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) against a group of abortion protestors who allegedly combined to drive them out of business. The issue was important for a host of financial and symbolic reasons. Racketeering, generally, is a form of organized crime that extorts money from businesses through means of intimidation or physical violence. If the courts allowed abortion protestors to be prosecuted under RICO, the symbolic effect would be negative for the pro-life cause. Just as importantly, if RICO was applied to pro-life groups, those groups would have to dip further into their finances to defend themselves against additional causes of action. Simply put, determining whether to apply RICO to pro-life groups had significant policy implications, and the Court’s decision to hear the case would therefore have profound consequences.

When the justices met during their private conference to decide if they would hear the case, each of them faced significant uncertainty. If they voted to hear it, would they be a part of the Court majority that created precedent? Would the result reached by the Court generate a policy more favorable to them than the status quo? And what did the legal considerations involved in the case suggest? Before voting to grant review to this politically charged abortion case, justices needed to answer these questions.

Our goal here is not to examine the Court’s abortion jurisprudence, nor is it to analyze how outside interests such as NOW influence the Court. These are topics that could, themselves, fill up numerous books. Instead, our goal is to explain the conditions under which justices set the Court’s agenda. We make three inter-related arguments. First, we argue that justices make probabilistic decisions when setting the Court’s agenda. They will cast their agenda votes based on the probability that the Court’s eventual decision will result in a more favorable policy than currently exists. Second, we argue that legal considerations, such as lower court conflict, judicial review, and legal importance influence justices’ agenda votes. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we argue that policy and legal considerations interactively influence justices’ agenda votes. When legal considerations and policy considerations point toward the same ends, a justice is freed up to follow her policy goals. But when the law points toward an outcome that the justice dislikes on policy grounds, she will often follow the law despite her policy misgivings. In short, we argue that policy and law jointly influence how justices set the Court’s agenda with policy sometimes giving way to law.

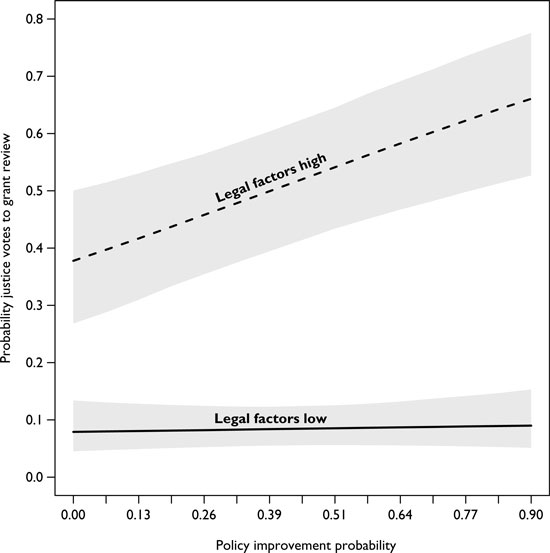

Our results support our hypotheses. We find, first, that justices make predictions about likely policy outcomes and vote to grant review, in part, based on these predictions. More specifically, as a justice’s probability of being made better off by the Court’s merits decision increases, the justice becomes increasingly likely to vote to review the case. Second, we observe that legal considerations also influence whether justices review cases. The presence of important legal cues strongly drive up the probability that a justice votes to review a case. And, finally, we find that policy and law interact, with law oftentimes conditioning justices’ policy behavior. Even justices who disagree entirely with the expected policy outcome of a case will vote to review it. These findings, of course, shed light on the Court’s agenda-setting process, but they also highlight a broader aspect of judicial decision-making, something we discuss more fully in the conclusion.

In what follows, we begin with a brief overview of the Court’s agenda setting, with the aim to let readers “look under the hood” of the process. We then provide a more detailed description of our theoretical argument and the hypotheses we derive from it. We next explain our data and results, and conclude with a discussion about Supreme Court agenda setting and judicial behavior more broadly.

The Nuts and Bolts of Supreme Court Agenda Setting

Modern Supreme Court justices have the discretion to determine which cases the Court will hear. Through a number of bills passed over the years, Congress has altered the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, changing the Court from one which was largely required to hear most of its cases (via mandatory jurisdiction) to one that could set its own agenda (via discretionary jurisdiction). When Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1891, it eased the Court’s workload burden by, first, creating the United States courts of appeals to hear all cases appealed from federal district courts and, second, carving out a small discretionary docket for the Supreme Court. As a result, with circuit courts hearing all appeals, justices had more power to select the cases they wanted to hear. Thirty-four years later, Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1925 which removed much of the Court’s remaining mandatory jurisdiction, leaving justices with even more power to set their own agenda. Finally, in 1988, Congress largely finished the job when it passed legislation that removed virtually all the Court’s mandatory jurisdiction. Accordingly, today’s justices can choose the cases they wish to hear, with little to no direction as to the types— or numbers—of cases before the Court (Owens, Stras, and Simon, n.d.).

In a moment, we will address the factors that lead justices to grant review to cases, but for now, we begin by providing background on how the Supreme Court sets its agenda. The process begins when a litigant asks the Court to hear its case, which most frequently means filing a petition for a “writ of certiorari” with the Court (i.e., a “cert petition”). Each year, the Court receives thousands of cases seeking its review, but elects to hear fewer than 100. For example, during the Court’s 2009–2010 session, justices received 8,159 requests to review lower court decisions, but opted to hear only 82 of them (Roberts 2010, 9–10).

Given the large number of review requests, justices have been forced to rely heavily upon their law clerks to help them study and review cert petitions. Starting in 1972, a group of justices created the “cert pool” by combining the collective efforts of their law clerks (Ward and Weiden 2006).1 Each clerk in the pool reviews a cert petition and reports back to the other justices and their clerks in the pool. That is, once the Court receives a petition, it is randomly assigned to one of the law clerks in the cert pool, who writes a preliminary memorandum (the “pool memo”) to the justices in the pool. The pool memo summarizes the proceedings in the lower courts and all legal claims made in the petition and response. It concludes with a recommendation for how the Court should treat the petition (e.g. grant, deny, or some other measure).

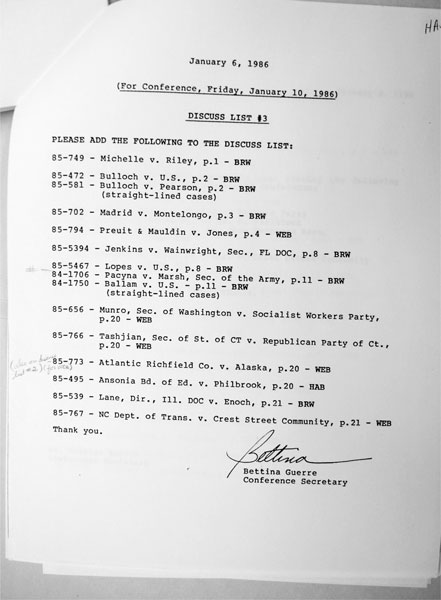

Relying on the pool memo and other materials, the chief justice then circulates a list of the petitions he thinks deserve further consideration from the Court at its next weekly conference. This list is called the “discuss list.” (We provide an example of a discuss list below in Figure 8.1.) Associate justices can add petitions to the discuss list that they think deserve a discussion, but they cannot remove from the list a petition that a colleague added.2 Importantly, the Court summarily (i.e., without a vote) denies all petitions that do not make the discuss list.

Figure 8.1 Discuss list for Court’s Conference on January 10, 1986. Initials next to each case correspond to the justice who put the case on the discuss list. We obtained this document from the Papers of Justice Harry A. Blackmun, which are housed in the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

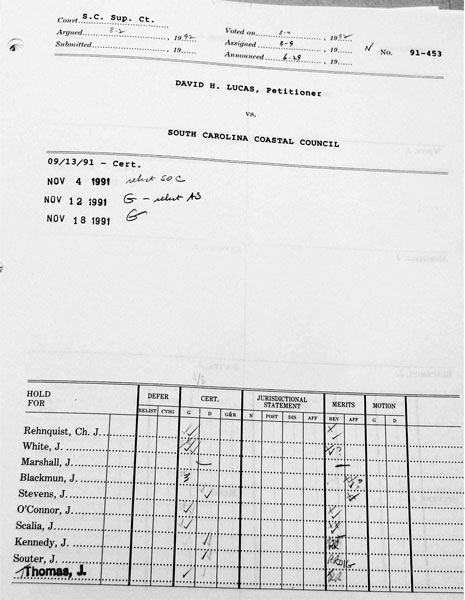

Each Friday, the Court holds a conference in which the justices discuss the cert petitions and vote on them. During this conference, the justice who placed the case on the discuss list (usually the Chief) leads off discussion of the petition. After presenting his or her views, the justice then casts an agenda vote. In order of seniority, the remaining justices state their positions and cast their votes. If four or more justices vote to grant review, the case proceeds to the merits stage.3 Figure 8.2 illustrates, using the vote in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, how the justices record their votes during these conferences. As this figure shows, the Court held two rounds of voting. Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices White, O’Connor, and Scalia voted to grant review in both rounds. Justice Blackmun voted to “Join-3” (that is, to provide the necessary fourth vote if there were three justices who supported review) in the first round and then to reverse summarily in the second round. Justices Stevens, Kennedy, and Souter voted to deny review in both rounds. Interestingly, we can see that Justice Thomas originally voted to grant review to the case but, in the second round of voting, switched his vote to deny. At any rate, because four justices cast grant votes, the Court granted review to the case and proceeded to the merits stage.

Figure 8.2 Justice Blackmun’s docket sheet in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003 (1992). Docket sheet comes from Epstein, Segal, and Spaeth (2007). Case granted review with four votes to grant (Rehnquist, White, O’Connor, and Scalia). Justice Blackmun voted for summary reversal. Justices Stevens, Kennedy, Souter, and Thomas voted to deny review.

Certiorari votes are entirely discretionary and, unless divulged by the personal papers of a deceased or retired justice, are completely secret. Neither the Court staff nor the justices’ own law clerks are allowed in the conference room during these deliberations. This secrecy, plus the Court’s lack of formal requirements for taking cases, leads us to our central question: under what conditions will justices vote to review a case?

A Theory of Supreme Court Agenda Setting

We argue that three broad considerations influence how justices set the Court’s agenda. We believe that justices vote to grant review to cases when they expect policy gains from hearing the case. We also believe that they will vote to grant review to a case when certain legal factors counsel toward hearing it. And, finally, we believe that policy and legal considerations interact with each other and jointly explain Supreme Court agenda setting. We address each of these factors below.

Policy Considerations

Like many before us, we argue that justices are seekers of policy who want to etch their preferences into law (Epstein and Knight 1998). “Most justices, in most cases, pursue policy; that is, they want to move the substantive content of law as close as possible to their preferred position” (p. 23). A number of influential studies highlight the role of policy in judicial decision-making. For example, Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck (2000) show that a justice’s decision to respond to a majority opinion draft—and to accommodate colleagues’ suggestions in those drafts—stem from ideological motivations. Martin and Quinn (2002), Bailey (2007), and Epstein et al. (2007a) provide sophisticated empirical models to show that justices can be located spatially according to their revealed policy preferences. Of course, Segal and Spaeth (2002) win the prize for making the most forceful argument about the role of policy, stating that “the legal model and its components serve only to rationalize the Court’s decisions and to cloak the reality of the Court’s decision-making process” (p. 53). Even scholars who are sympathetic to the potentially constraining effect of law on justices concede that policy is the predominant motivation that drives justices (see, for example, Richards and Kritzer 2002).

Yet, justices must pursue their policy goals in an interdependent environment in which their decisions are also a function of the preferences of those with whom they must interact. Most important for our purposes, justices must interact with their colleagues on the Court. This requirement (to acquire a majority to make binding precedent) influences justices’ behavior throughout the decision-making process (Bonneau et al. 2007; Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000). Chief justices and Senior Associate justices who assign majority opinions do so to make favorable policy, but they also must keep the majority coalition together. Opinion writers must also make sure that their opinions reflect the preferences of their colleagues, lest they lose their support and find themselves writing in dissent. This means pre-emptively accommodating their colleagues and, when necessary, making changes to opinion drafts. In order to make binding precedent, justices must engage in such practices (Hansford and Spriggs 2006). They must predict how their colleagues will act throughout the decision-making process. These and other studies, then, show that policy matters dearly to justices, but that they must also—at all times—consider how their colleagues’ responses will affect their eventual policy success.

We believe that at the agenda stage, justices will engage in similar behavior: they will seek their policy goals but will also look to the behavior of their colleagues to determine whether they will be in the majority or in the minority in a case. That is, when deciding whether to grant review to a case, justices must consider and predict the likely behavior of their colleagues at the merits stage. To win on the merits, a justice must be able to join with at least four of her colleagues. In short, they must predict the behavior of their colleagues when they set the Court’s agenda, and determine whether their colleagues’ predicted behavior at the merits stage will improve policy for them, or make worse policy than the status quo.

Numerous comments from justices and their clerks provide strong evidence to support the argument that justices are forward-looking agenda setters. Consider the following statement taken from H.W. Perry’s (1991) seminal text on agenda setting: “I might think the Nebraska Supreme Court made a horrible decision, but I wouldn’t want to take the case, for if we take the case and affirm it, then it would become a precedent” (H.W. Perry 1991, 200). Clearly, this quote suggests that justices base their agenda decisions, at least in part, on the existing status quo and the expectations about their colleagues’ behavior. Similar types of comments can be found throughout the papers of former Justice Harry A. Blackmun. Consider the following in Dupnik v. Cooper (No. 92–210), in which Blackmun’s clerk advised him: “This is a defensive deny if nothing else.” Or, look at Freeman v. Pitts (No. 89–1290) in which Blackmun’s clerk stated: “[G]iven the current mood of the Court, I am not eager to see the petition granted.” Indeed, consider the following quintessential quote from Blackmun’s clerk in Thornburgh v. Abbott (No. 87–1344):

I think it pretty much comes down to whether you want to reverse the judgment below (the likely outcome of a grant). If you are pretty sure you do, you should vote to grant now. Otherwise, it’s better to wait.

(Epstein, Segal, and Spaeth 2007)

We seek to build on these and other works by showing that justices make probabilistic forward-looking agenda-setting decisions. We examine how justices behave when they predict a range of possible merits outcomes rather than one specific outcome. In other words, rather than assuming that the Court’s merits outcome can be reflected by the ideal point of, say, one justice (see, for example, Black and Owens 2009a), we argue that justices predict the Court’s merits outcome will fall within a certain range of probable outcomes. To be sure, it may be defensible to assert that actors know the policy location of the status quo and the preferences of colleagues with whom they must frequently interact. It is problematic, however, to assume that actors have complete and perfect information about the final result of the policy they will make—especially when that policy must undergo treatment from other actors (such as their colleagues). Predictions will seldom be perfectly accurate, particularly when making decisions in multi-stage settings. What is needed is an approach that examines how justices make probabilistic predictions under conditions of uncertainty.

We argue that when the probability increases that the Court’s expected merits decision will be better for a justice than the status quo, the justice will be more likely to vote to grant review to the case. Conversely, when that probability decreases, the justice will be less likely to vote to grant review to the case. The logic is obvious: justices will seek to open the gates and allow cases to proceed when their probability of winning at the merits increases, and they will be less likely to open those gates when the probability of winning on the merits decreases. This gives rise to the following hypothesis:

Probabilistic Policy Hypothesis: a justice will become increasingly likely to vote to grant review to a petition as the probability increases that the Court’s merits decision will be better policy for that justice than the status quo.

While policy considerations clearly are important for justices, so too are legal considerations. After all, justices are trained in the law and taught, like all lawyers, that the law is sacrosanct and must be followed. At the same time, other actors such as Congress, the president, the public, and the bar expect justices to respect the law. Since justices rely on these institutions to execute the Court’s decisions and sustain its legitimacy, they must behave in a manner consistent with those expectations. So, justices wanting to make efficacious decisions must largely comply with predominant beliefs about proper legal behavior (Lindquist and Klein 2006).

What are these legal considerations that influence justices at the agenda stage? To answer this question, we reviewed two well-known studies on Supreme Court agenda setting—H.W. Perry (1991) and Stern et al. (2002). Both of these works illuminate the legal factors that influence justices’ agenda votes. H.W. Perry (1991) gained insight into the Court’s agenda behavior through a number of extensive interviews with justices and their clerks, while Stern et al. (2002) rely on years of experience within the Court and litigating before it. Perry argues that legal conflict and legal importance constitute two (empirically testable) legal variables, while Stern and his co-authors argue that judicial review exercised in the lower court is an important legal factor driving the Court’s agenda. The importance of these factors has been verified by a number of studies (see, for example, Black and Owens 2009a). We consider each of them more extensively.