Studying Cases Empirically: A Sociological Method for Studying Discrimination Cases in Sweden Reza Banakar

7

Studying Cases Empirically: A Sociological Method for Studying Discrimination Cases in Sweden

REZA BANAKAR

This paper uses two previous studies of unlawful discrimination, which I carried out in Sweden in 1992 and 1996, to develop a more comprehensive sociological method for studying anti-discrimination laws.1 The initial question asked in these studies concerned the impact of the Swedish Act against Ethnic Discrimination (hereafter the AED), ie, how the legal system dealt with unlawful discrimination and to what extent it counteracted discriminatory practices using the AED. The data used comprised official studies of various aspects of immigrants’ and ethnic minorities’ conditions in employment and occupation, open interviews with various groups such as lawyers and immigrants, a study of the discourse on ethno-cultural relations in Sweden, and discrimination cases. The focus of this chapter will be on the limitations of discrimination cases which were used in the studies of ethnic discrimination in Sweden.

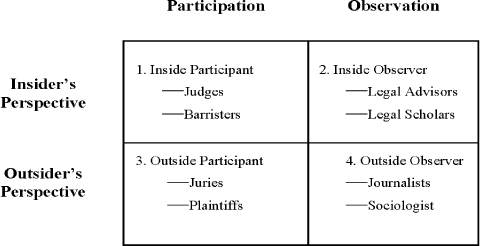

The following is divided into two sections. Section One provides a brief account of how the first two studies were conducted by focusing on the communicative practices through which the cases were processed and decided. The experience of conducting these studies is then used to discuss the limitations of legal documents as empirical data. In Section Two, I propose a new approach to the study of unlawful discrimination, which uses the experiences gained from the previous studies to argue that each case has its own specific social structure.2 The social structure of each case can be explored by highlighting the interaction—conceptualised in terms of communicative action—between the perspectives of various actors, ie, parties to the dispute, officers of the court, judges, or ombudsmen, who together create the case. The focus then becomes how the perspectives of various actors and their perceptions of law, interact with each other to bring about a specific outcome. The actor’s perspective varies in accordance with his/her standing in relation to the law and his/her involvement in legal processes. My approach moves from a mere concern with the impact of law on unlawful discrimination to a more fundamental concern with how legal rules, doctrines, legal decisions, institutionalised cultural and legal practices work together to create the reality of law in action.

A. TWO STUDIES OF THE AED

1. Background

The Swedish Parliament enacted its first piece of legislation specifically designed to counteract ethnic discrimination in 1986.3 This legislation did not contain provisions prohibiting ethnic discrimination in recruitment and/or employment.4 Instead, it created the Office of the Ombudsman against Ethnic Discrimination (hereafter the Ombudsman)5 and entrusted the Ombudsman with the task of counteracting discrimination through information—ie, by informing public opinion of what ethnic discrimination was—and by scrutinising the actions of employers. The law gave the Ombudsman the necessary legal power to demand from employers against whom a complaint was lodged explanation for their alleged discriminatory treatment of job seekers or employees. However, it did not provide sanction against ethnic discrimination in the labour market and working life. The AED (1986) was heavily criticised for neglecting ethnic discrimination in recruitment and employment, as a result of which it was revised and amended after eight years.6 The amended AED7 gave the Ombudsman greater powers to counteract ethnic discrimination legally and became Sweden’s first anti-discrimination legislation to protect ethnic minorities (primarily immigrants) in the labour market. The AED (1994) did not, however, cover the entire recruitment process. The employers could simply evade short listing applicants with foreign names or backgrounds and in this way exclude them from being considered seriously for a job opening, without the risk of being sued. Also, the Act fell short of making any impact on indirect discrimination, which meant that employers could use seemingly objective procedures to exclude certain ethnic groups from participation in the labour market. For example, they could demand proof of proficiency in Swedish for jobs which required limited verbal or written skills, which would exclude some immigrant groups. Finally, the AED (1994) placed the burden of proof on the claimant, making it extremely difficult to demonstrate that direct discrimination had actually taken place. As a result, and despite the fact that the necessary legal powers to take cases to the Labour Court were conferred on the Ombudsman by the AED (1994), the Ombudsman succeeded in taking only one case to court, which, incidentally, he lost.8

Not surprisingly, criticism against the AED (1994) soon mounted and a proposal for a new AED with further amendments was submitted to Parliament and enacted in 1999. The AED has, therefore, gone through three distinct stages in its transition from an anti-discrimination law without specific provisions prohibiting unlawful discrimination in working life to a law with sanctions against direct and indirect discrimination. Although it might be of interest to consider each of these stages separately, this task falls outside the present undertaking. Instead, we shall limit our discussions to the first two stages of the development of the AED.

To sum up, although the AED (1986) created a starting point for preventing ethnic discrimination in public and private services, it nonetheless fell short of providing explicit sanctions against ethnic discrimination in the labour market. This law also set up the Office of the Ombudsman against Ethnic Discrimination and entrusted it with the task of eradicating ethnic discrimination from all walks of life including the labour market, which the legislature ironically left unregulated in this regard. One of the initial questions motivating this research focused on the Ombudsman’s ability to counteract unlawful ethnic discrimination in the labour market, which is arguably the most damaging form of racial discrimination. This question was of special interest because the Ombudsman lacked a legal instrument empowering him to force employers to comply with a non-discriminatory policy. In the first of the two studies mentioned above, I used cases from 1990, when the AED had not yet provided sanctions against unfair treatment of job applicants and employees on ethno-cultural grounds. In the second study, I used data collected after the enactment of the amended AED in 1994, which did contain such sanctions.15

The empirical data used in these studies consisted of cases processed by the Ombudsman and were collected in two separate phases in 1990 and 1995. The first set of data was based on a qualitative study of all cases lodged with and processed by the Ombudsman in 1990. In that year the Ombudsman registered 736 cases, of which roughly half were complaints about ethno-cultural conflicts. The second set of data is from 1995, reflecting the amended AED of 1994 in action. The Ombudsman registered about 1000 cases during 1995, more than half of which concerned ethnic discrimination. From these cases I selected 78, of which 73 were directly related to discrimination in the labour market. These cases were chosen primarily to examine the amendment which recognised the need to protect ethno-cultural minorities in the labour market by prohibiting ethnic discrimination in working life. The question was whether the amendments, which gave greater power to the Ombudsman did, in fact, help to curb unlawful ethnic discrimination against job applicants and employees. At the time when these 73 cases were selected (at the end of 1996) they constituted all the major processed cases on discrimination in the labour market that were registered during 1995 by the Ombudsman. (A handful of cases which had been lodged during 1995 were still being processed in 1996.) This choice of data allowed the study to focus on labour-related ethnic discrimination. It also made it possible to explore the changes which were brought about as a result of the amendments to the AED (in 1994) that directly addressed ethnic discrimination in the labour market for the first time.

Although, as pointed out above, most of the selected cases concerned ethnic discrimination in working life, I nonetheless included examples of cases that did not concern strictly ethno-cultural disputes and did not directly have a bearing on the problem at hand. These were chosen to provide an insight into the diversity of the cases lodged with the Ombudsman.

2. The Method of Investigation

The two studies mentioned above followed three methodologically distinct but interrelated stages. These stages can be briefly described as: 1) gaining an overview of the empirical data in order to formulate a number of working hypotheses; 2) constructing a preliminary conceptual apparatus to conduct a systematic substantive analysis of the empirical data; and 3) attempting to develop the theoretical basis of the investigation. The theoretical framework of this study was, therefore, developed in view of the available data. As pointed out above, the bulk of the material used in this study consisted of ethnic discrimination cases. The cases ordinarily contained two types of information: 1) a letter of complaint which provided the complainant’s account of a dispute with a second party; and 2) a record of how the dispute was processed by the Ombudsman. Occasionally, an account of the Ombudsman’s correspondence with the second party and/or of the response from the second party towards whom the allegation of discrimination was directed was also included. The cases were systematically registered and kept at the Ombudsman’s archive in Stockholm. Going through all the cases which were processed by the Ombudsman during 1990 constituted the first phase of the analysis of the empirical material.

This initial stage of the study was carried out in an inductive manner and aimed at describing the properties of these cases. The result indicated that the cases contained sufficient information to answer socio-legal questions on issues such as conflict resolution, policy implementation, regulation of public administration, discretion, the rule of law and legal decision-making. However, the information contained in the files was limited from a sociological point of view in the sense that it revealed little or nothing about the social psychological mechanisms of ethnic discrimination. The data contained in the files did not provide clues of causal relations between racial attitudes and discriminatory practices, which meant that they could not be used to examine, for example, why certain ethnic groups were systematically excluded by employers while others were recruited.

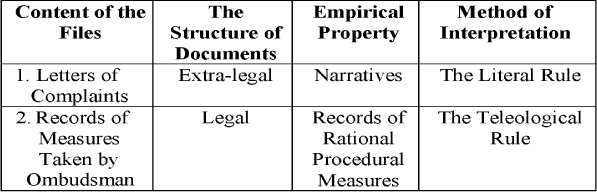

In interpreting the complainants’ written presentations (and also any second party’s responses) attempts were made to follow the so-called ‘literal rule’ according to which words that are reasonably capable of only one meaning must be given that meaning whatever the result.16 Where possible, I tried to let the texts of the complaints ‘speak for themselves’. I do not, however, claim that a pure literal interpretation is possible, but I used this method in an attempt to contain certain side-effects of textual analysis. In other words, this method of interpretation helped to an extent to avoid attaching to the texts and words meaning that transcended their everyday usage and was not intended by the author of the texts.

However, a different interpretative approach was employed to analyse legal records. The legal documents produced by the Ombudsman and other authorities were interpreted broadly and in a teleological fashion.17 This was because many aspects of laws, directives and guidelines, which were used by the Ombudsman to decide cases, were formulated broadly and resembled policy declarations.18 These laws and directives left leeway for the Ombudsman to process each case by taking into consideration its social and legal properties. This approach also enabled me to take into account the social functions of the Ombudsman as envisaged by the legislature. Diagram 1 illustrates the types of document and methods adopted to interpret their contents.

Diagram 1

The initial analysis of cases demonstrated that they provided a valuable source of information on various types of disputes related to ethnicity. The contents of the files also depicted the legal and extra-legal strategies developed by the Ombudsman to process these conflicts and the way in which the legal system subsequently dealt with them. However, as pointed out above, despite the fact that most of the complaints were concerned with ethnic discrimination, the files could not offer a reliable basis for investigating the social psychological causes of ethnic discrimination. As a result, the scope of the analysis was restricted to questions on which the empirical data could throw light. Thus, research questions were formulated concerning 1) the types of conflicts presented to the Ombudsman, 2) the strategies which were adopted by the Ombudsman to deal with them, and 3) the subsequent socio-legal effects that were brought on by the application of these strategies. These effects revealed how such concepts as discrimination, ethnicity, race or racism were reproduced within the legal system and used for legal decision-making and how law’s understanding and definitions of these concepts impacted on ethnic discriminatory behaviour and race relations.

The objective of the initial stage was to gain an overview of the material in order to formulate a number of working hypotheses. The second stage aimed to devise a theoretical instrument. A conceptual apparatus was needed which could facilitate a substantive examination of the contents of the cases and provide us with plausible answers to the research questions. Again going back to the empirical material, three major areas were identified which needed to be addressed theoretically. These were: 1) communication, 2) conflict or dispute, and 3) modes of dispute resolution.

I defined the process of lodging a complaint with the Ombudsman and the Ombudsman’s subsequent handling of it in terms of communication. In order to develop this idea further, I used the theory of communicative action as my main theoretical framework to grasp and analyse the legal system’s application of procedural processing of complaints.19 Thus, the method of investigation used here was developed through a close interplay between the available empirical data, the research questions posed and the relevant theoretical constructs within the sociology of law.

Stage three, using cases filed in 1995, was conducted in accordance with the initial research questions. It was, moreover, concerned with assessing the possible impact of the amended AED on ethnic discrimination and developing the theoretical basis of this investigation further. The remaining part of this section is devoted to presenting some of the insights gained by the initial investigation of the cases. These insights concern the strategies used by the Ombudsman to deal with conflicts and the types of disputes brought before the Ombudsman.

3. Processing Complaints and the Ombudsman’s Gate-keeping Techniques

The Ombudsman reviews complaints brought before him/her by deciding: 1) if the complaint concerns ethnic discrimination or is related to ethno-cultural issues; 2) if the dispute as it is expressed and presented by the complainant is bona fide, in the sense that it provides adequate grounds for legal action, or to put it differently, if some aspects of the dispute can be subsumed under a legal rule and therefore can be brought within the domain of legal regulation; and 3) in cases where there is a bona fide dispute, what further legal measures may be taken to process the case successfully. In this sense the Ombudsman acts as the first ‘gatekeeper’ of the law on ethnic discrimination, selecting the cases which may enter the normative sphere of legal meaning.

This model depicts a rather simplified picture of the way in which the Ombudsman processes discrimination complaints. Any decision to include or exclude a complaint involves statutory interpretation, which in turn involves making value judgements on many issues. Some of these issues are legally pertinent and concern fundamental principles underlying the due process and the rule of law. Other issues involve social psychological factors or political values, which are not recorded in the cases and are, therefore, difficult to isolate empirically in the available data.

I should add here that the procedure underlying this gatekeeping technique is far from unique to the Ombudsman, and is also employed by other legal authorities. The procedural model below closely reflects the process of subsumption used by the functionaries of the legal system. Scholars as diverse in their sociological orientations as Ronon Shamir and Niklas Luhmann have grappled with and theorised this process. Shamir argues that we need to understand the role of law in terms of its modus operandi