Sino-Japanese Conflict and Reconciliation in the East China Sea

Chapter 8

Sino-Japanese Conflict and Reconciliation in the East China Sea1

Introduction

The past two decades have witnessed growing obsession over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in both China and Japan. This trend has been especially pronounced in Japan since September 2010. To outsiders this dispute is especially striking given that these islands appear to be essentially barren rocks. The current obsession is an aberration, given that since the normalization of Sino-Japanese relations in 1972 both sides took steps to avoid having this territorial conflict harm the larger bilateral relationship. Looking at the longer history of the islands, through much of history China and Japan, and to a lesser extent the Kingdom of Ryukyu, were often barely conscious of these small rocky islands’ very existence. Within the Sino-centric tributary system these islands were essentially an undefined borderland (Suganuma 2000, pp. 102–29).

The recent and novel obsession regarding these islands appears to be fueled by growing nationalism on both sides that powers a spiral of growing tension and in turn further fuels this nationalism. This trend is especially pronounced in Japan, where, in contrast to China, the Senkaku Islands had relatively low salience among the general public before 2010. Although Japanese public opinion remains firmly opposed to using military force overseas, there is a broad consensus that military power has utility for defending national territory (Midford 2011a), and Japanese overwhelmingly see the Senkakus as Japanese territory worth defending (NTV 2010).

A second underlying factor driving this action-reaction spiral and nationalist fervor on both sides has been a legal dynamic internal to the dispute itself, where both sides have seen the actions of the other as undermining their own claim to the islands under western international law. Paul O’Shea (2012, pp. 8–12) has labeled the related political dynamic the “sovereignty game.” This has led both sides to try to compete in demonstrating effective control over the islands (mostly Japan) or disrupt the other’s exercise of effective control (mostly China).

Up to 2010, both China and Japan saw the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute of secondary importance and took steps to ensure that this dispute did not damage overall bilateral relations. Since 2010 this pattern has reversed as both sides have increasingly acted to strengthen their sovereignty claims over the islands even at the cost of damaging the larger relationship. Consequently, it is not an exaggeration to argue that the island dispute has become the single most important issue in bilateral relations.

A third variable that has been stoking the current confrontation in the Senkaku/Diaoyu conflict is the fact that it has been occurring during a period of geopolitical power transition, as China rises, and Japan, and to a lesser extent the US, have experienced relative decline. This creates some uncertainty regarding the balance of military capabilities between China on the one hand, and Japan and, to a lesser extent, the US on the other hand. Moreover, US interest in this territorial dispute itself is low, and Washington has manifested concerns about becoming entrapped in a military conflict there. Power transition also creates incentives for the parties to this dispute to act more aggressively in staking their sovereignty claims, thereby destabilizing and exacerbating the conflict. China, as a rising power, might perceive that a shift in the balance of power in its favor allows it to become more territorially assertive in exercising effective control.2 On the other hand, a Japan in relative decline and pessimistic about the future direction of the balance of power vis-à-vis China would have an incentive to act more aggressively in order to consolidate a relatively favorable territorial status quo before the distribution of capabilities shifts further against it. Recent research indicates that the period of Japan’s relative decline beginning in the 1990s corresponds with a rising assertiveness in staking and consolidating its maritime territorial claims, and not just vis-à-vis China (Manicom 2010; O’Shea 2013).

The spiral of nationalist tensions and the action reaction dynamic that emerged between the two countries since 2010, and especially since 2012, one that involves frequent confrontations between the coastguards of the two nations, has arguably become the most dangerous territorial dispute in East Asia and the most likely regional trigger of a great power military confrontation outside of the Korean peninsula, eclipsing even the Taiwan issue. Unlike the many other maritime territorial disputes in East Asia, the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands are unique in the sense that they are the only one where the US is bound by treaty commitment to become involved in the case of military conflict. This makes this maritime dispute uniquely dangerous, as it is perhaps the only conflict at present that could directly trigger a Sino-US military conflict.3

The high stakes of the present confrontation, ongoing more or less since 2012, suggest the policy relevance of conflict de-escalation measures and even longer term conflict resolution measures, even while nationalism on both sides limits the likelihood of actually adopting any of these measures. After examining the underlying dynamics, especially those stemming from western international law, which led to the current confrontation, this chapter will consider several measures for de-escalation and long-term settlement of the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue, and even the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) dispute between China and Japan. This chapter does not claim that any of these measures are likely to be adopted, but given the stakes, it is worth considering what de-escalation and longer term conflict resolution might look like.

The rest of this chapter is divided into seven sections. The next section looks at how a September 2010 confrontation became a turning point in the bilateral relationship and especially the territorial and EEZ conflicts between the two countries in the East China Sea. The following section examines how the 2010 confrontation affected mass and elite opinion in Japan, and Japan’s defense strategy. The section after that analyzes how the conflict reemerged and reached a new level of intensity in 2012, with this confrontation still ongoing at the time of writing. The following section shows the role of Western international law in exacerbating the conflict over these islands. The following two sections then outline proposals for short-term conflict de-escalation and long-term conflict resolution of both the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute and the related EEZ dispute. The concluding section reviews both the causes and possible solutions to these disputes.

September 2010 as a Turning Point

Traditionally, both China and Japan have worked to keep bilateral tensions over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands from damaging overall bilateral relations, especially economic relations.4 When the issue has flared up, both countries have acted to quickly tamp down tensions and insulate the rest of the relationship (Green 2003). For example, bilateral fisheries cooperation was traditionally insulated from the bilateral territorial dispute; fishing around the islands (as per the 1997 bilateral fisheries agreement) was defined as a fisheries issue, not a territorial one.

This all changed as a result of a September 2010 altercation between patrol vessels of Japan’s Maritime Safety Agency (MSA) and a Chinese fishing boat. This incident had profound implications for Sino-Japanese relations, and especially on Japanese perceptions of China. Most fundamentally, this incident raised the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island dispute to the top of the bilateral agenda, despite previous attempts by both sides to prevent this dispute from disrupting the extremely important bilateral relationship.

On September 7 this Chinese fishing boat collided with two Japanese MSA (coastguard) vessels that were attempting to make the boat leave the territorial waters of the Senkaku Islands that Japan claims and effectively controlled, causing minor damage to the two coastguard cutters. In response, the Japanese coastguard vessels seized control of the Chinese boat and took it to Ishigaki Island, where the captain was arrested on suspicion of obstructing the official duties of MSA personnel, a crime that carries a maximum punishment of up to three years in jail. On September 10 an Okinawan court granted Ishigaki prosecutors’ request to extend the captain’s detention for 10 days to prepare for possibly filing criminal charges (Ito 2010; Japan Times 2010; Kyodo 2010).

The issue soon escalated into a bilateral confrontation, with China demanding that the ship’s captain be released, as the crew and the boat had been. China rejected Japan’s jurisdiction to indict the captain, citing their own territorial claims to the Senkaku Islands, started cancelling bilateral meetings, and began deploying fisheries protection vessels near the islands. Beijing also suspended rare earth shipments to Japan, and four Japanese company employees were arrested in China on suspicion of videotaping in a restricted military zone. Both developments were widely seen in Japan as an attempt to “bully” Tokyo into releasing the captain (e.g., Daily Yomiuri 2010), although whether either development was actually related to the bilateral dispute over captain’s arrest (rather than being a coincidence) has been questioned (Hagström 2012).

China appeared to fear that putting the captain on trial would further demonstrate Japan’s effective control over the Senkaku Islands, thereby weakening China’s claim to the islands under international law. The captain’s arrest was the first time that Tokyo had applied domestic Japanese domestic law in waters around the islands. Sino-Japanese fisheries agreements from 1975 and 1997 avoided the territorial issues in these waters by specifying that flag-state jurisdiction (i.e., the country from which the fishing vessel originated) be applied. In other words, the waters around these islands were treated as high seas (Gupta 2010). Japan even refrained from applying domestic law to prosecute Chinese activists who had landed on the Senkaku Islands in 2004 and destroyed Japanese property there, most notably a Shinto Shrine (Asahi Shimbun 2004a, 2004b; O’Shea 2012, p. 21; Yomiuri Shimbun 2004). In the 2010 confrontation, the DPJ applied domestic Japanese law, apparently unaware of previous LDP governments’ policy of not doing so and their tacit understandings with China. Most notably, after the brief 2004 confrontation China and Japan reportedly reached a secret agreement under which Japan agreed not to prosecute Chinese activists who land on the islands, and China undertook to prevent activists from landing on the islands (Aera 2010).5

On September 25 the prosecutor’s office in Ishigaki, citing “the effects on the people of Japan and the future of Japan-China relations,” announced the release of the ship’s captain without any charges being filed (Asahi.com 2010a; Asahi.com 2010b). The reaction from opposition parties was vociferous, with the Kan administration being accused of pressuring prosecutors to release the ship’s captain. In response to Kan’s claim that “the decision was made by the prosecutor’s office,” Itsunori Onodera of the LDP claimed the captain’s release was Japan’s “biggest foreign policy blunder in the postwar era” (Yomiuri Shimbun 2010). Meanwhile, Takeo Hiranuma, head of the Sunrise Party, claimed “releasing the captain could be interpreted as Japan implicitly recognizing China’s territorial claim” (Asahi.com 2010a; Martin and Ito 2010). Yomiuri Shimbun cited a senior disgruntled DPJ member as claiming that neither Kan nor his ministers “knows anything about diplomacy. They just released the skipper in a flutter after being intimidated by China. China will probably continue to make unreasonable demands on Japan … [because] of this country’s lack of mettle” (Yomiuri Shimbun 2010; Midford 2013).

The Impact of the 2010 Confrontation on Japanese Public and Elite Views of China

The September 2010 conflict over these very small islands had a big impact on bilateral relations, especially on Japanese perceptions of China. China came to be seen as a threat that had to be dealt with through coercive force. When asked how the Kan cabinet should respond to the situation surrounding the Senkaku Islands in a Nippon TV poll, over 40 percent supported involving the SDF either through MSDF destroyer patrols (24.4 percent) or by stationing GSDF personnel on the islands (17.8 percent). Another 30.7 percent supported strengthened MSA patrols. In other words over 70 percent of respondents favored strengthened coercive (military or police) measures. By contrast, only 1.2 percent supported talking with China about the Senkaku Islands. In answer to another question in the same NTV poll, 61 percent of respondents stated that the Senkaku fishing boat incident had caused their view of Chinese to worsen somewhat or very much (NTV 2010).6

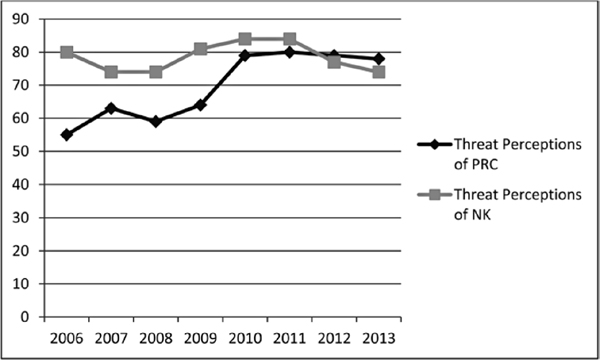

Figure 8.1 Japanese threat perceptions of China have overtaken those of North Korea

Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, Nichibei kyoudou yoron chousa, normally conducted in early December.

Most strikingly, the annual Yomiuri Shimbun poll on Japan’s bilateral relations, which is usually conducted in December, showed a sizable shift in public threat perceptions of China following the September 2010 bilateral confrontation over the Chinese ship captain’s detention. The results can be seen in Figure 8.1 above. In short, this poll found that between 2010 and 2012, China overtook North Korea as the most cited potential military threat to Japan. Given that North Korea had long been considered the leading threat, this shift is significant (it also reflects a subsequent and worse confrontation in 2012, see below).

There was a parallel shift in Japanese elite opinion as well. Before 2010, few Japanese elites had seen China as posing a military threat to Japan. Until September 2010 Japanese policy makers had growing concerns about China’s military modernization, but did not have significant concerns about Chinese conduct.

However, following the 2010 fishing boat incident this attitude changed.7 Recurring standoffs and tensions around the Senkaku Islands are the main reason for why Chinese intentions are increasingly seen as aggressive. Consequently, Japanese defense and foreign policies are increasingly refocusing on how to respond to this threat.

The first clear indication of this came with the 2010 National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG, or Bouei Taiko), which has been Japan’s most basic defense policy document (until 2013). Up to 2010 all of Japan’s post-Cold War Bouei Taikos (including the 1996 and 2004 NDPGs) were focused on responding to a perceived North Korean threat, or, in the case of the 2004 NDPG, nontraditional threats such as terrorism; none of them focused on a China threat. The 2010 NDPG was the first one to focus on China. Most notably, it called for strengthening the defense of the southern Ryukyu Islands (or Sakishima Islands) near the Senkakus and Taiwan, a region that currently has no Japanese military bases (except for a radar and listening post on Miyakojima Island) and has been called a “security vacuum” by Japanese defense officials. With the Democratic Party of Japan’s (DPJ) 2010 Bouei Taiko, Japanese officials began planning to place a small Ground Self-Defense Forces (GSDF) unit on Yonaguni, the island closest to Taiwan and the Senkakus, ostensibly for enhancing military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in the area (including the Senkakus) with a maritime radar. This unit might theoretically be able to act as a first responder to a crisis in the Senkaku Islands (Midford 2011b). There have also been discussions about deploying some F-15s just off nearby Ishigaki Island. At the same time Japan is developing its first amphibious assault unit in the GSDF, with help from the US Marine Corp, to enhance its ability to retake remote islands. Finally, the 2010 NDPG called for Japan to increase its submarine force by over one third, from 16 to 22, the largest single buildup in the force in the post-war era, and a buildup that is clearly aimed at China. The submarine buildup will give Japan greater abilities to quietly monitor and control the seas around the Senkakus and Japan’s other remote islands and to exploit one of the Chinese navy’s largest vulnerabilities, namely its paucity of anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities, while avoiding the threat posed by China’s new anti-ship ballistic missile (which cannot target submarines).8