Section 112: Suspending Performance

SECTION 112: SUSPENDING PERFORMANCE

The Introduction of a Statutory Right to Suspend Performance | |

The 2009 Act: Suspending Performance of Any or All of its Obligations | |

(1) Overview

Introduction and Summary

15.01 This chapter considers s. 112, which creates a statutory right for a payee to suspend performance for non-payment. It examines the conditions which must apply for the right to arise, and looks at the consequences of both a proper and improper exercise of the right. The key issues relating to suspending performance are:

1. The right to suspend arises when the sum due or notified sum has not been paid in full by the final date for payment.

2. The payee must give at least seven days’ notice of its intention to suspend.

3. Where the right to suspend is operated correctly, payees may be able to apply for loss and expense directly incurred as a result of the suspension as damages for breach of contract. Under the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’), the contractor’s right to an extension of time is limited to the actual period of suspension. The Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (‘the 2009 Act’) has attempted to clarify the contractor’s rights to claim loss and expense and an extension of time.

4. If a payee exercises its suspension rights incorrectly, this may amount to a repudiatory breach of contract entitling the payer to terminate. However, this will depend upon the nature of the breach, and the facts and circumstances of the case.

(2) The Statutory Right to Suspend Performance

The Introduction of a Statutory Right to Suspend Performance

15.02 Section 112 of the 1996 Act created a statutory right for a contractor or subcontractor (a payee) to suspend performance of a contract for non-payment. Before the 1996 Act came into force, the common law did not recognize a remedy of withholding contractual performance whilst keeping the contract alive.1 A payee who suspended or deliberately slowed down work in response to non-payment ran the risk of being found guilty of a breach of a contractual obligation to proceed regularly and diligently with the works.2 Whilst delay to completion is not normally treated on its own as repudiatory, especially where the contract allows for liquidated damages,3 there was a risk that suspension might be seen as sufficiently serious to be judged repudiatory. Unsurprisingly, few payees took this risk.

15.03 Notwithstanding the statutory backing now given to acts of suspension, there have been very few reported instances of payees suspending work under the provisions of the 1996 Act. Respondents to a consultation conducted by the Department of Trade and Industry in June 20074 indicated that the right was being exercised in fewer than 1 in 100 cases of non-payment.

15.04 The mere availability of the remedy is likely to have deterred most payers from failing to make timely payment. This, combined with the relatively well-understood payment provisions in ss. 109 and 110(1) and the statutory right to adjudicate, has no doubt contributed to the lack of reported decisions concerning suspension. However, the lack of clarity in the 1996 Act suspension provisions (discussed below) and the wish to avoid a reputation as a (sub)contractor who suspended works, may have also contributed to an under utilization of this provision.

Supplemental to Other Rights

15.05 Section 112(1) provides that the right to suspend work is ‘without prejudice to any other rights or remedy’. Thus interest remains payable on the late payment, either under the contract or pursuant to the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act 1998. In certain cases, an unpaid payee may also be entitled to treat the contract as repudiated and terminate its performance of it, provided that the amount or manner of the underpayment is such as to indicate that the payer is unwilling or unable to meet its contractual obligations.5

15.06 The right to suspend is therefore supplemental to these rights, and because it is derived from statute, it will override any term of the contract which purports to exclude or limit its application. Accordingly, any contractual provision which purports to alter the statutory conditions under which the payee may suspend, such as the introduction of longer notice periods or a ‘cooling off’ period after the final date for payment during which the payee cannot suspend, is likely to be ineffective. However, agreed conditions which merely seek to deter the payee from exercising its statutory right to suspend, such as making the payee liable for the costs of de-mobilization and re-mobilization, may be valid under the 1996 Act.

The 2009 Act Amendments

15.07 The right to suspend under the 2009 Act has been broadened in order to deal with the issues discussed above. The changes are discussed in the relevant sections below.

(3) Suspending Performance

What Is Required for the Right to Suspend to Arise?

15.08 The conditions necessary for exercising the right to suspend are set out in s. 112(1)–(4) of the 1996 or 2009 Act and may be summarized as follows:

1. A payment has become due.

2. No effective withholding or pay-less notice has been served.

3. The final date for payment has passed.

4. Payment has not been made in full.

5. The payee has given a valid seven-day notice of intention to suspend.

Each of the above conditions is examined in turn in the paragraphs below.

15.09 If in doubt as to whether any of these requirements have been met, a payee may decide to seek a declaration from an adjudicator or the court under CPR Part 8 before suspending performance. There would appear to be no reason why such an application could not be sought during the notice period for suspension, allowing the payee to serve a suspension notice first and stop work once the adjudicator or court has given its decision, if full payment has not been made in the meantime.

A Payment Has Become Due

15.10 Section 112(1) of the 1996 Act provides that the right to suspend arises ‘[w]here a sum due under a construction contract is not paid in full’. However, the question of what sum is due is not always straightforward. See Chapter 13 for a discussion of the issues and potential difficulties with how to ascertain the sum due.

15.11 For contracts entered into after 1 October 2011, s. 112(1) is now activated if the payer has not paid the ‘notified sum’. In theory, this should be more straightforward as the notified sum will be either the sum set out in the payer’s or specified person’s payment or pay-less notice, or else in a payment notice or application provided by the payee. However, these new provisions will be subject to the inevitable teething problems as the industry comes to grips with the new payment regime and four possible sources for the ‘notified sum’.

15.12 Whether under the 1996 Act or the 2009 Act, the right to suspend does not arise where the payee simply disagrees with the amount that has been certified or is included in the payment notice. In such cases, the payee will need to bring adjudication or other proceedings to have the amount adjusted.

No Effective Withholding or Pay-less Notice

15.13 The requirements for a withholding or pay-less notice to be effective are set out at 13.87 and following, and call for the notice to be served within the contractual time limit (or that statutorily implied by the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’)) and to contain certain information depending on whether the 1996 or 2009 Act applies.

15.14 If the payee considers a withholding or pay-less notice to be ineffective, either because it is late or because it is insufficiently particularized, then the payee may be entitled to suspend performance. Clearly in such cases the payee is running a risk since, if wrong, it may be held to be in breach of contract (possibly repudiatory breach) and liable for damages by suspending.6

The Final Date for Payment Has Passed

15.15 The right to suspend arises under both the 1996 and 2009 Acts if the relevant sum has not been paid in full by ‘the final date for payment’, which is discussed at 12.26–12.27.

15.16 This suggests that the right to suspend starts from 00.01 hours on the day following the final date for payment. This is important since, if the payee suspends work too soon, it loses the statutory protection of s. 112 and may be in breach of contract. However, since the suspension must in any event be preceded by seven days’ notice, any doubt should be capable of being resolved by stating clearly in the notice when the payee considers the right to suspend to have arisen and when it will be exercised.

Payment Not Made in Full

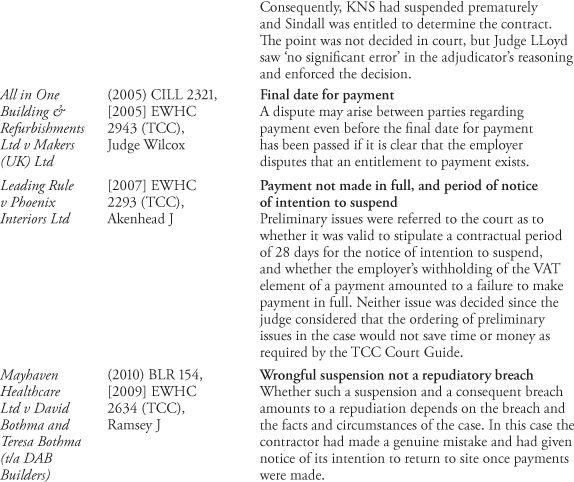

15.17 Provided that a sum due or notified sum can be established, then it should be a simple matter to determine whether or not payment has been made in full. The question of whether a contractor could suspend, and eventually determine, the contract for non-payment of VAT due on a payment ordered by an adjudicator arose in Leading Rule v Phoenix Interiors Ltd (2007);7 however the court declined to answer the issue. Therefore there is no judicial guidance on this point.

A Valid Notice of Intention to Suspend Performance

15.18 Section 112(2) provides that the right to suspend may not be exercised without first giving the party in default ‘at least seven days’ notice’ stating the ground(s) on which it is intended to suspend performance. The drafting of this subsection is imprecise and neither expressly excludes the parties from agreeing a longer notice period nor requires that the final date for payment should first have passed before the payee gives notice.

At Least Seven Days’ Notice

15.19 The requirement for ‘at least’ seven days’ notice has been interpreted by some payers as allowing the parties to stipulate a longer notice period in the contract. A report in 2000 of the Construction Liaison Group found that a longer period had been specified in 20 per cent of cases, and in 25 per cent of these the contracts stipulated a notice period in excess of 21 days.8

15.20 However, it is notable that s. 112, unlike s. 111(3) for example, does not expressly state that the parties are free to agree an alternative notice period. It is therefore possible that the intention of Parliament was that the seven days’ notice period should not be interfered with and that the words ‘at least’ are intended simply to imply a discretion for the payee to extend the notice period if it appears that payment might be forthcoming.

15.21 The question was almost put to the test in Leading Rule v Phoenix Interiors Ltd (2007),9 in which the lay adjudicator had decided that a contractual notice period of 28 days was valid and that Phoenix had suspended its performance of the work too early. However, Akenhead J declined to rule on that matter and the case proceeded no further in the courts.

15.22 It should be noted that s. 116 provides that Christmas Day, Good Friday, and bank holidays should be excluded for the purpose of calculating time periods under the Act.10 These days do not count, therefore, as part of the seven days’ notice period.

Anticipatory Notice

15.23 The decision in All in One Building & Refurbishments Ltd v Makers UK Ltd (2005)11 suggests that a dispute crystallizes as soon as it is clear that the payer does not intend to fulfil its obligations to make payment on the date required. Therefore, in theory, a payee could give an ‘anticipatory’ notice before the final date for payment if it considers that payment is unlikely to be forthcoming, and suspend performance as soon as both the final date for payment has passed and the notice period expired. This has not been specifically tested by the courts.

Contents of the Notice

15.24 The question of what information is necessary in the notice was considered in the case of Palmers Ltd v ABB Power Construction Ltd (1999)12 although, once again, the judge in that case decided that the matter was not one on which he should give judgment. This case indicates, however, that the courts will treat very seriously any mistake on the face of the notice which might undermine the grounds upon which the right to suspend is claimed. It perhaps underlines that suspension is still viewed as a drastic remedy despite its validation by the 1996 Act, and that the notice needs to be unambiguous for the payer to avoid the consequences of any perceived inaction.

When to Suspend Performance?

15.25 Once the right to suspend has arisen and the notice period has expired, it appears that the payee may suspend performance immediately, or wait for a further period before suspending. The right continues to apply until payment of the full amount is made,13 and therefore it is likely that the payee will retain the right to suspend even if it does not exercise it immediately.

What to Suspend?

The 1996 Act: Suspending Performance of its Obligations

15.26 Section 112(1) of the 1996 Act permits an unpaid party to ‘suspend performance of his obligations under the contract’. However, it does not actually prescribe what this means in practice. Is it required to cease all work being performed, or can it keep certain services operating during the period of suspension? Can it operate a ‘go slow’ or perhaps cease cooperating in terms of attending meetings with the payer or ceasing to perform difficult items such as achieving planning permission? Is it possible for a payee to suspend its obligation to provide a parent company guarantee or collateral warranty?

15.27 In the absence of express wording in the contract, the payee may be free to do any of these things provided that they can properly be termed a ‘suspension’ of its obligations under the contract. Indeed, the payee may be within its rights to take the wording of s. 112(1) at face value and suspend all operations with immediate effect, including removing security guards and leaving the works in the condition they were in at the moment the notice period expired. The potential cost consequences of such a decision are discussed below.

15.28 Some adjudicators or courts may distinguish ‘obligations under the contract’ from obligations which arise under statute, such as Health and Safety laws or CDM Regulations. It is thought that a payee should exercise caution before suspending such statutorily imposed obligations, particularly without warning the payer of such an intention.

The 2009 Act: Suspending Performance of Any or All of its Obligations

15.29 The position may be different for contracts entered into after 1 October 2011 when the 2009 Act came into force. Amendments to s. 112(1) provide an express right for the contractor to suspend ‘any or all’ of its obligations under the contract which would appear to avoid the doubts set out above by expressly allowing a partial suspension.

15.30 Having suspended performance, the employer is liable to pay the contractor a reasonable amount in respect of costs and losses reasonably incurred as a result of the exercise of its right (s. 112(3A). It is important to note, however, that there is no express obligation of reasonableness inserted in the amendments to s. 112(1). Accordingly, it is suggested that there is no requirement that the act of suspension itself be subject to any test of reasonabless—it is an absolute right in the event of non-payment (subject to the necessary steps desicribed above being taken).

When Does the Right to Suspend Cease?

15.31 Section 112(3) states that the right to suspend performance ‘ceases when the party in default makes payment in full’ of the amount due. Therefore, if the payee fails to resume performance as soon as payment is made, it loses the protection of the Act (whether 1996 or 2009) and may be in breach of contract. The requirement for immediate re-mobilization remains untested however, and it may be the case that the courts, recognizing the difficulties involved in reassigning staff, subcontractors, and equipment quickly to the site, would allow some leeway to prevent the payer profiting from its own breach.

(4) The Consequences of Suspension

The Consequences of a Wrongful Suspension

15.32 Where any of the required elements discussed above are not in place, a suspension may be deemed invalid or unlawful. This may in turn put the payee purporting to exercise its statutory right to suspend into repudiatory breach of contract.14 However, a bona fide but mistaken reliance on an express provision of a contract to suspend performance is not, alone, to be treated as a repudiatory breach—the suspension will be viewed in light of all the facts and circumstances of the case: Mayhaven Healthcare Ltd v Bothma and Bothma (2009) (Key Case).15

15.33 It is notable that the 2009 Act extends the right to claim costs and expenses only to the payee, and not the payer. This means that the payer has no statutory protection against the risk of wrongful suspension. However, the payer may revert to contractual or common law remedies to obtain compensation for the breach, including accepting what he considers to be a repudiatory breach of contract by termination.

The Consequences of a Valid Suspension

Entitlement to Loss and Expense

15.34 The 1996 Act does not expressly provide for compensation for the loss or expense incurred during the period of suspension. Such costs might include:

1. the costs of standing or off-hiring equipment

2. costs of reassigning or laying off staff

3. the consequential costs of re-mobilization

4. compensation to subcontractors for periods of inactivity

5. the possible risk of dilapidations or defects resulting from works being left unfinished.

15.35 Whilst some standard-form contracts deal with this situation by providing that the payee is entitled to its additional costs as a result of suspending works under the Act,16 many contracts do not.17 As a result, whilst the payee might recover its payment due before the suspension, it might still face having to bring an action for breach of contract against the payer to recover its additional costs, with no certainty of recovery. Such costs should be recoverable as general damages for breach of the payment obligations in the contract, provided there are no provisions to the contrary such as an exclusive remedies clause. One specific cost is worth mentioning: if the payee suspends security to the site, and damage occurs to the works during the period of suspension, then under the 1996 Act, no claim would lie against the contractor for that damage as the contractor was under no obligation to the employer at the time the damage occurred. Although the contractor may be contractually obliged to rectify defects in the works, it should be able to claim the costs of doing so as damages for the payer’s breach of contract.

15.36 The 2009 Act seeks to clarify s. 112, and ensures that the payee now has a statutory right to claim loss and expense which should apply even in cases where the contract contains an exclusive remedies clause. However, the obligation under the new s. 112(3A) extends only so far as ‘a reasonable amount in respect of costs and expenses reasonably incurred as a result of the exercise of the right’. Whether the amendments have the effect of widening the recovery or whether they in fact limit the rights that the payee otherwise had at common law to claim loss and expense is yet to be seen.

15.37 In order to avoid a future charge that costs have been unreasonably incurred, it is suggested that payees should set out in their notice of intention to suspend the steps that they intend to take in furtherance of that right. If these include suspending the whole of their operations, then the notice should preferably state this. It would also be prudent to check the terms of the contract to see what provision is made for the care of the work and to keep these issues under review throughout the period of suspension. At least if the payer is placed on warning of the consequences of its breach, it may not later complain that it had no opportunity to arrange replacement security or take steps to prevent damage from occurring to the partially constructed works.

Entitlement to Extension of Time

15.38 Section 112(4) of the 1996 Act provides that for the purposes of calculating time for the completion of the works, ‘[a]ny period during which performance is suspended in pursuance of the right conferred by this section’ is to be disregarded. This appears to mean that the payee is entitled to an extension of time equal to the period of suspension. It should be noted that the wording of this section does not allow the payee to claim the actual delay to the works, which may of course be much greater than the period of suspension itself. However, the contract administrator may be permitted by the terms of the contract to give an extension which takes into account the consequences of disruption if they exceed the period of the suspension itself. In addition, it is possible that a court might construe this period as including such matters as disruption to programme and de- and re-mobilization to prevent the payer profiting from its breach.

15.39 The amendments to s. 112 introduced by the 2009 Act now cover ‘any period during which performance is suspended in pursuance of or in consequence of the exercise of the right conferred’. Whilst this amendment is clearly intended to permit the payee to claim periods of de- and re-mobilization as well as the actual period of suspension, some consider it doubtful that it has made the situation any clearer than before. In particular, it may be unclear during a period of re-mobilization at what stage the works might be said to have restarted for the purposes of assessing the period of suspension. It is perhaps unfortunate that the drafting of the 2009 Act did not take the opportunity to provide that it is ‘the delay to the works consequent on the suspension’ which determines the extension of time to which the payee is entitled. This would at least have avoided issues as to when the works have been fully recommenced and would have allowed the payee an extension of time in respect of any consequential disruption. However, as discussed above, it is possible that the payee may be able to claim for such consequences in any event.

15.40 Particular problems may arise where the suspension occurs after the contract completion date, and thus at a time when the payee is already in culpable delay. In such cases, depending on the terms of the contract, it seems that an extension of time may still be granted18 and that the appropriate length of the extension remains the length of time that works are actually suspended whether before or after the contract completion date. In other words, the suspension should not deprive the payer from claiming liquidated damages in respect of the periods both before and after the payee’s suspension.

15.41 Many standard forms contain particular clauses prescribing how events which are not the payee’s responsibility will be assessed and it may be difficult in practice to reconcile the statutory entitlement with the contractual entitlement. The period following payment of the outstanding debt is likely to be fraught with difficulties in relation to agreeing the length of extension and loss and expense to which the payee is entitled. However, there is no statutory right for the payee to prolong the suspension whilst these matters are sorted out. The payee must decide either to return to work or maintain that the payer’s continued intransigence in matters of payment amounts to a repudiation and terminate the contract accordingly.