Section 108 and the Right to Adjudicate

SECTION 108 AND THE RIGHT TO ADJUDICATE

(1) Introduction

3.01 Section 108 of the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’) contains the right to adjudicate. It sets out the minimum requirements that a contractual adjudication scheme needs to contain in a construction contract governed by the 1996 Act.

3.02 This chapter considers the provisions of s. 108 concerning what disputes may be adjudicated and when. Certain aspects of s. 108 are dealt with in more detail elsewhere in this book and so are touched on only briefly below, in particular; the duty to act impartially (s. 108(2)(e)) is dealt with in Chapters 10 and 11, the adjudicator’s power to take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law (s. 108(2)(f)) is also considered in Chapters 4 and 10. The binding nature of the adjudicator’s decision (s. 108(3)) is the subject of Chapter 6.

3.03 The focus of this chapter is the statutory right to adjudicate. It does not discuss adjudication schemes in contracts not governed by the 1996 Act. In practice many construction contracts contain more detailed adjudication procedures than the Act requires. A party wishing to adjudicate a dispute under a construction contract must first consider whether any contractual adjudication scheme complies with the Act. If so, it is a valid adjudication procedure and any adjudication will be governed by the rules contained in that contractual adjudication scheme. Any supplementary provisions in that adjudication scheme will still be valid in principle, as long as they do not conflict with the statutory requirements.

3.04 Naturally there are contracts which are outside the ambit of the Act but that nevertheless contain an adjudication scheme. A contract which is not a construction contract within the meaning of Part II of the Act is not required to have an adjudication procedure. Nor does a contract with a residential occupier need an adjudication procedure. If such contracts contain an adjudication scheme, it does not have to comply with the statutory requirements. In such a situation, the absence of a matter that the 1996 Act considers to be fundamental will not usually render that contractual adjudication scheme invalid. Nevertheless many of the legal doctrines developed in relation to statutory adjudications are applicable to these pure contractual adjudications. Chapter 5 contains a discussion of whether the principles applicable to adjudication under the 1996 Act apply also to adjudication agreements in other contracts.

Changes Made by the 2009 Act

3.05 One of the main changes made to the 1996 Act by the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (‘the 2009 Act’) is the deletion of s. 107 and the requirement that construction contracts be in writing (as discussed in Chapter 2). At the same time s.108 was amended so that the adjudication provisions required by s. 108(2)–(4) must now be in writing,1 and this means that in contracts entered into after October 2011 it is only the adjudication procedure that must be in writing.2 Failure to properly express any of the adjudication procedures in writing will result in the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’) becoming applicable.3

3.06 The only other change to s. 108 is the introduction at new s. 108(3A) of the requirement that the construction contract must include, in writing, a provision permitting the adjudicator to correct his decision ‘so as to remove a clerical or typographical error arising by accident or omission’. The power to correct a decision, both before and after the 2009 Act, is discussed in Chapter 4.

(2) Issues Arising Out of s. 108(1)

3.07 Section 108(1) provides that a party to a construction contract (as defined by ss. 104 and 105) has the right to refer a dispute arising under the contract for adjudication under a procedure complying with s. 108.4

3.08 The meaning of s. 108(1) has been tested in numerous cases where the enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision has been challenged. The most common issues arising out of s. 108(1) are dealt with in the sections that follow and in summary are:

(1) whether there is a dispute ‘arising under the contract’ as required by s. 108(1);

(2) whether the matter referred to the adjudicator had crystallized into ‘a dispute’;

(3) whether s. 108(1) requires a single dispute only to be referred;

(4) whether the scope of the dispute referred was different from that which had crystallized or changed during the adjudication and the effect of that.

3.09 These four questions are considered below. These questions are matters that may go to the jurisdiction of an appointed adjudicator, because, in a statutory adjudication, an adjudicator is appointed to decide ‘a dispute’ that ‘arises under the contract’. If the issue referred to him is not ‘a dispute’ or does not arise under the contract, then it is not a matter that the statute empowers him to decide.5 Accordingly, s. 108(1) must be satisfied before a party may make use of the right to adjudicate contained within it.

Disputes Arising under the Contract

3.10 It goes without saying that the statutory right to adjudicate only arises in respect of construction contracts within the meaning of Part II of the Act. Therefore there must be a qualifying construction contract in existence which satisfies ss. 104–76 in order for a valid adjudication to be started. These provisions are the subject matter of Chapters 1 and 2.

3.11 Section 108(1) provides that the right to adjudicate concerns disputes ‘arising under’ the contract. Much of the attention given to this section has focused on what constitutes a ‘dispute’ but it is equally important for a referring party to ensure that the claim it wishes to adjudicate does ‘arise under’ the relevant construction contract.

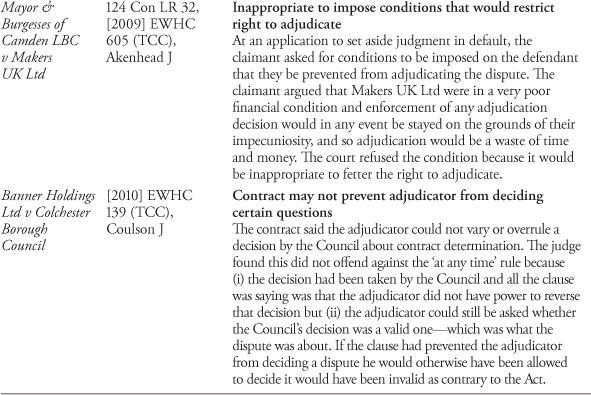

3.12 Ashville Investments v Elmer Contractors Ltd (1987) 7 is authority for the proposition that an arbitration clause which covers disputes arising under the contract but also includes the words ‘in connection with’ should be given a wide interpretation and will cover related claims for rectification, negligent misstatement, and the like. When the Court of Appeal applied that decision in the later case of Fillite (Runcorn) Ltd v Aqua-Lift (1989),8 they concluded that an arbitration clause which encompassed all disputes ‘under’ the contract (but did not contain the additional words ‘in connection with’), embraced claims for breach of contact but, in the words of Slade LJ, was ‘not wide enough to include disputes that do not concern obligations created by or incorporated in that contract’.

3.13 In relation to arbitration clauses, in Fiona Trust & Holding Company and ors v Yuri Privalov (2007)9 the House of Lords said it was to be assumed that the parties, as rational businessmen, were likely to have intended any dispute arising out of the contract, including disputes over the validity of the agreement itself, were to be decided by the arbitrator, unless express words excluded certain disputes from the arbitrator’s jurisdiction. However, the 2009 Act has not amended s. 108(1) to include disputes arising ‘in connection’ with the contract and it is submitted the ambit of s. 108(1) remains limited to disputes under the contract. In Camillin Denny Architects Ltd v Adelaide Jones & Company Ltd (2009)10 Akenhead J expressed uncertainty as to whether Fiona Trust was authority for any proposition about an adjudicator’s jurisdiction.

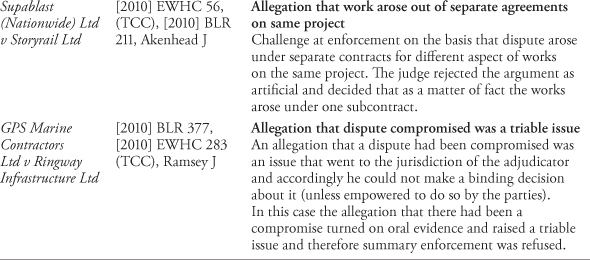

3.14 Whether a particular type of dispute ‘arises under’ a contract is discussed below. Other than this and the requirement that a single dispute is referred (see 3.31 below) s. 108 contains no limit on the nature, scope or extent of the disputes that can be referred to adjudication under a construction contract; Banner Holdings Ltd v Colchester Borough Council (2010).11 In that case the TCC judge said that the contract could not validly prevent a dispute about the validity of a contractual determination from being a matter that could be referred to adjudication.12

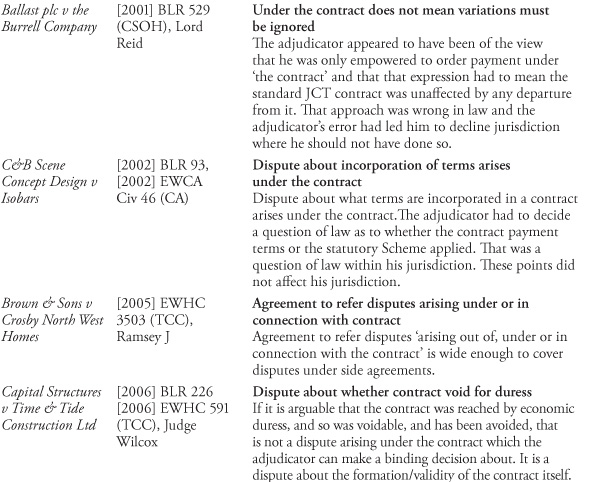

Side Agreements

3.15 Whether an adjudication agreement will be wide enough to cover disputes about side agreements will depend on its wording: Brown & Sons v Crosby North West Homes (2005).13 The agreement in this case had been amended to refer to disputes arising under, out of, or in connection with the contract and was found to be wide enough to cover terms in side agreements.

Dispute under More than One Contract

3.16 If the dispute arises under more than one contract, then it may be that part of the dispute does not arise under the contract and cannot be referred to adjudication. If it is two disputes they cannot be referred to the same single adjudication without the consent of the parties (see 3.49 below) or unless this is permitted by the adjudication procedure. However in the cases in which this question has arisen the courts have usually avoided that result.

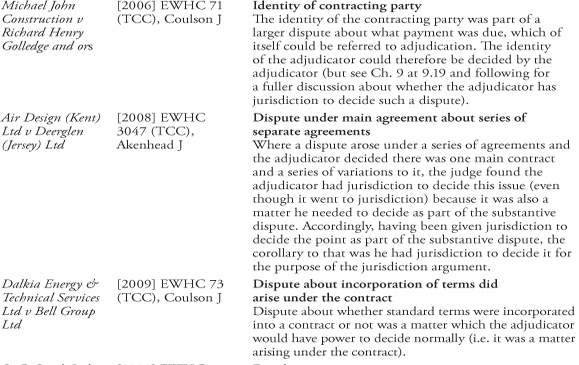

3.17 In Air Design (Kent) Ltd v Deerglen (Jersey) Ltd (2008)14 there was an original contract and a number of supplementary agreements. The adjudicator decided the subsequent agreements were variations of the original contract and that he had jurisdiction under the original contract adjudication agreement to consider disputes arising under that contract or variations to it. At the enforcement hearing Akenhead J decided that the adjudicator had been empowered to decide that issue (because it was a question of fact and/or law) and so the decision was enforceable whether right or wrong.

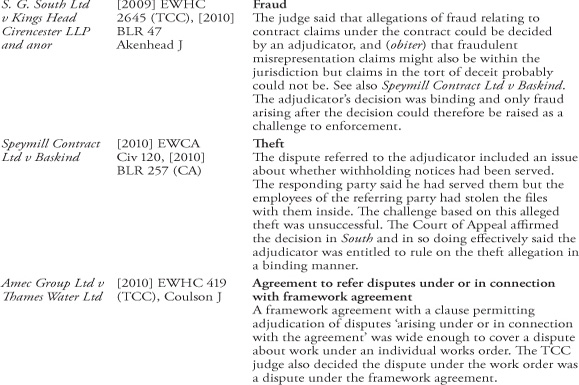

3.18 In Amec Group v Thames Water Utilities Ltd (2010)15 the written adjudication agreement was contained in a framework agreement and applied to disputes ‘arising under or in connection with’ that framework agreement. Under the framework agreement work was instructed as separate works packages forming separate contracts. The TCC judge decided that the dispute in question arose under the framework agreement but that in any event the wording of the adjudication clause was wide enough to cover a dispute arising under the individual works orders.

3.19 In Supablast (Nationwide) Ltd v Story Rail Ltd (2010)16 the TCC judge rejected the challenge to enforcement on the ground that the dispute arose under two separate contracts, finding that the adjudicator had had jurisdiction to decide that the steelworks were instructed as a variation to the subcontract.

Identity of Contracting Party

3.20 In Michael John Construction v Richard Henry Golledge and ors (2006)17 the defendant argued that a dispute concerning the correct identity of the employer, which required consideration of documents such as the club constitution, was a dispute ‘in connection with’ but not ‘under’ the construction contract. The judge decided that the issue, as to the individuals who were liable (on behalf of the employer) to make proper payment to the claimant under the contract, was part and parcel of the single dispute referred to the adjudicator. In this case the employer under the contract was named as the Club. The claimant was simply seeking to be paid by the Club under the contract by reference to the Trustees at the time that the contract was made. The judge found that this was plainly a dispute concerned with the obligations owed under the contract by the employer to the contractor and that accordingly the adjudicator was empowered to decide this question.18

Contract Formation

3.21 A dispute about the formation of the contract itself is not a dispute arising under the contract. It is a dispute about whether a relevant contract came into existence for the purpose of the 1996 Act or s. 107. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Incorporation of Terms

3.22 A question about whether a particular term has or has not been incorporated into an agreement is a matter which the adjudicator19 has power to decide:

Thus so long as it is established or agreed that there is a contract in existence between the parties, that it is a construction contract … any other dispute as to the terms of the construction contract is as much a dispute arising under the contract as would be a dispute as to the working through of any terms to the valuation machinery.20

The same decision was reached in Dalkia Energy & Technical Services Ltd v Bell Group Ltd (2009).21 This is consistent with the rule that an adjudicator does have the power to interpret or construe the contract. In C&B Scene Concept Design Ltd v Isobars Ltd (2001)22 the Court of Appeal decided that, even if the adjudicator had been wrong in his decision as to which of two competing sets of terms were incorporated into the contract, it was a decision he was empowered to make and the decision was binding. If however the incorporation argument is really a question of an oral agreement of a term of the contract which has not been evidenced by writing, that is a s. 107 matter which goes to jurisdiction.

Rescission

3.23 In Barr Ltd v Law Mining Ltd (2001)23 the responding party argued that the contract had been rescinded and the claim for payment for work done after that rescission could not be determined by the adjudicator as it did not arise under the contract. The adjudicator declined to answer the rescission issue but awarded sums for the relevant work. At the enforcement hearing Lord Macfadyen held that the adjudicator would only have had jurisdiction if he had first decided that there had been no rescission. The court was of the view that liabilities incurred after a contract has been rescinded are not within the jurisdiction of the adjudicator.

Duress

3.24 If the contract itself, such as a settlement agreement, was obtained as the result of economic duress by one party, it is a voidable agreement. In Capital Structures v Time & Tide Construction Ltd (2006)24 Judge Wilcox decided that it was arguable that a settlement agreement had been avoided before the adjudicator assumed jurisdiction. If correct this would have meant there was no contract at all. As that was a dispute that went to the formation of the contract it was not one the adjudicator could make a binding decision about. Summary enforcement of the decision was refused.

Settlement Agreement

3.25 A dispute about the validity of a settlement agreement is not a dispute under the construction contract itself: Shepherd Construction v Mecright Ltd (2000).25 However a claim that the dispute has been compromised is an issue that goes to the the jurisdiction of the adjudicator and may be a ground for challenging enforcement.26

Fraud

3.26 In S. G. South Ltd v Kings Head Cirencester LLP and anor (2009)27 a developer challenged the summary enforcement of adjudicator’s decisions on the ground, inter alia, that there had been fraud on the part of the contractor. The allegations had been raised before the adjudicator who had decided that fraud was not an issue within his jurisdiction because it was a matter for the police and the courts. The TCC judge stated obiter that there is nothing in the 1996 Act to suggest that an adjudicator does not have jurisdiction to decide issues of fraud which arise under a contract. However the judge suggested that a claim in the tort of deceit would probably not arise under contract, but thought that a claim for fraudulent misrepresentation might do. This was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Speymill Contracts Ltd v Baskind (2010),28 which confirmed the approach taken in the two previous TCC decisions.29 For a discussion of when a party may rely on fraud as a defence to enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision, see Chapter 7 at 7.09.

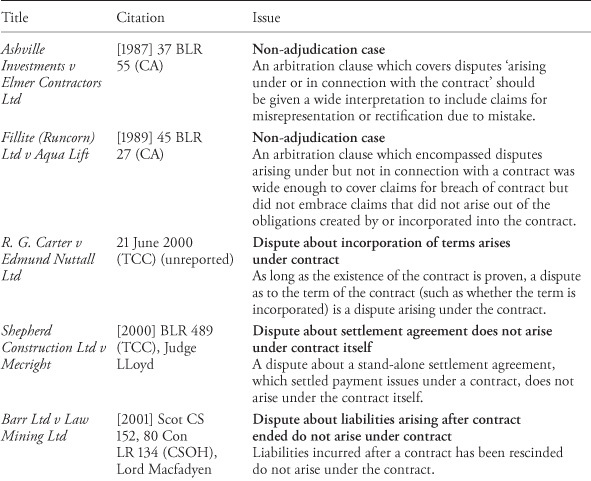

Key Case: ‘Arising Under’

Table 3.1 Table of Cases: ‘Arising Under’

What Constitutes a ‘Dispute’ for s. 108(1)?

3.29 Section 108(1) provides that a party to a construction contract has the right to refer a dispute arising under the contract for adjudication under a procedure complying with s. 108. For this purpose s. 108(1) tells us that a ‘dispute’ includes ‘any difference’. It is thus a statutory precondition to the right to adjudicate that there is in existence a dispute capable of being referred. It is significant that the Act does not say that the contracting parties may refer any claim or issue to adjudication. It must be a claim which has become a dispute.

3.30 There have been a large number of cases on the subject of when a claim or issue becomes a dispute, as can be seen from Table 3.2 at the end of this section. However, since the Court of Appeal has given guidance on the subject in Amec Civil Engineering Ltd v The Secretary of State for Transport (2005) (Key Case)30 and Collins (Contractors) Ltd v Baltic Quay Management (1994) Ltd (2004),31 the early cases are relevant as historical background to what is now the settled position. The following paragraphs deal briefly with that background.

The Early Cases: The High-threshold Test

3.31 After the 1996 Act was passed, there were not infrequent challenges to the enforcement of adjudication decisions on the ground that the matters referred to the adjudicator had not yet crystallized into a ‘dispute’ that could be referred, and so (it was argued) the decision was invalid, the condition precedent of s. 108(1) not having been fulfilled. The ‘no dispute’ arguments followed several typical lines which included (1) respondents claiming they had not had sufficient time to consider the issue before the notice of intention to refer was served; (2) respondents arguing they had not been given sufficient information about the issue to understand it before the notice of intention to refer was served; (3) respondents arguing that the issue referred to adjudication differed in material ways to that which had been previously discussed by the parties.

3.32 The view was expressed in the early cases that a dispute arose only after the claim had been notified to the opposing party who had been given the opportunity of ‘considering and admitting, modifying or rejecting the claim or assertion’: Fastrack Contractors Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd (1999).32 In Sindall Ltd v Abner Solland and ors (2001)33 Judge LLoyd considered that for there to be ‘a dispute’ for the purpose of exercising the statutory right to adjudication it must be clear that ‘a point has emerged from the process of discussion or negotiation has ended and that there is something that needs to be decided’.34 The high-water mark of that trend is found in Edmund Nuttall Ltd v R. G. Carter Ltd (2002)35 and a later decision of the same judge in Hitec Power Protection BV v MCI Worldcom Ltd (2002).36 In those cases Judge Seymour expressed his view that, for the purposes of adjudication, a dispute crystallized when both sides had been given sufficient opportunity to consider the arguments of the other, and also that the dispute which crystallized included ‘the whole package of arguments advanced and facts relied on by each side’. The rationale behind this early line of authority was to prevent respondents from being ambushed in adjudication by large claims of which they had little notice such that they were disadvantaged in preparing their defence. Unfortunately what also happened was that respondents sought to take advantage of the prevailing trend by cynically trying to prevent disputes from crystallizing. This delayed adjudications and frustrated the purpose of the Act.

The Adoption of the Halki Low-threshold Test

3.33 In the Birmingham TCC however, Judge Kirkham decided in November 200237 that there was no special meaning to the word ‘dispute’ in the context of adjudication, and that the Court of Appeal decision in Halki Shipping Corporation v Sopex Oils Ltd (1998)38 was binding in the context of adjudication. The Court of Appeal in Halki, dealing with an arbitration agreement, had set the threshold standard required to establish there was a dispute at a relatively low level: ‘There is a dispute once money is claimed unless and until the defendants admit that the sum is due and payable.’39 Putting it another way, if letters written by the claimant making some request or demand are not responded to by the defendant, then there is a dispute. The majority of the Court of Appeal also decided that a dispute exists whether or not the issue is disputable as a matter of fact or law. Thus a denial of liability by the respondent, no matter that the denial is based on a demonstrably incorrect interpretation of the law, is still a dispute. Subsequently in Beck Peppiat v Norwest Holst Construction Ltd (2003)40 Forbes J also held that the decision in Halki was binding in the context of adjudication.41 Following Cowlin and Beck Peppiat the High Court cases tended to adopt the lower and more conventional threshold test for identifying a dispute capable of being referred to adjudication.42

The Court of Appeal Guidance: The Middle Ground

3.34 In Amec Civil Engineering Ltd v The Secretary of State for Transport (2004) (Key Case) Jackson J attempted to distil the effect of the rapidly growing jungle of decisions on the meaning of ‘a dispute’. That was a case concerning whether a dispute existed within the meaning of clause 66 of the ICE conditions that could be referred to the engineer for decision, as required by that clause, and then subsequently referred to arbitration. The judge conducted a review of the principal authorities, including those arising in the context of arbitration and adjudication, from which he derived seven propositions. Those are set out in full in the Key Cases at the end of this section. In essence the judge decided that the mere fact that one party notifies the other party of a claim does not automatically and immediately give rise to a dispute. A dispute does not arise unless and until it emerges that the claim is not admitted. The circumstances from which it may emerge that a claim is not admitted are changeable, depending on the circumstances of the case. The circumstances may involve express rejection, implied rejection after discussions, or implied rejection after a period of silence or prevarication.

3.35 Jackson J’s seven propositions were broadly accepted by the Court of Appeal in Collins (Contractors) Ltd v Baltic Quay Management (1994) Ltd (2004).43 Subsequently the Court of Appeal were asked to consider an appeal from Jackson J’s judgment in Amec and once again his seven propositions were endorsed by the members of the court.44 May and Rix LJJ each added their own additional observations on the issue which are set out verbatim in the Key Case extracts below. In so far as the existence of a dispute involves affording a party a reasonable time to respond to a claim, what may constitute a reasonable time depends on the facts of the case and the relevant contractual structure.45 On the facts in Amec, May LJ agreed with Jackson J that the short deadline for response to the claim imposed by the Secretary of State was reasonable in the circumstances, not least because limitation was in danger of expiring imminently.46 In his additional observations, Rix LJ resurrected the idea that, in the context of adjudication, the reasonable time to respond may be influenced by the need to avoid prematurely plunging parties into expensive adjudications before they are ready:

68. Thirdly, and significantly, the problem over ‘dispute’ has only really arisen in recent years in the context of adjudication for the purposes of Part II of the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996. Jackson J referred below to some of the burgeoning jurisprudence to which the need for a ‘dispute’ in order to trigger adjudication has given rise. In this new context, where adjudication is an additional provisional layer of dispute resolution, pending final litigation or arbitration, there is, as it seems to me, a legitimate concern to ensure that the point at which this additional complexity has been properly reached should not be too readily anticipated. Unlike the arbitration context, adjudication is likely to occur at an early stage, when in any event there is no limitation problem, but there is the different concern that parties may be plunged into an expensive contest, the timing provisions of which are tightly drawn, before they, and particularly the respondent, are ready for it. In this context there has been an understandable concern that the respondent should have a reasonable time in which to respond to any claim.

3.36 The cases decided after Amec and Collins, as set out in Table 3.2 at the end of this section, have followed the guidance given by the Court of Appeal in those decisions and the meaning of ‘dispute’ in s. 108 of the Act now seems to be reasonably well settled.

3.37 An example of the robust approach that the courts take in relation to this type of challenge is illustrated by All In One Building & Refurbishments v Makers UK Ltd (2006).47 Prior to the adjudication, the claimant did no more than assert its claim for loss of overheads and profits against the defendant and then particularized the claim in the adjudication itself. The defendant argued that that there was no dispute in relation to this element of the claim when the adjudication was commenced. Judge Wilcox rejected this argument, stating that a common-sense approach needed to be adopted and ‘there is no warrant for being legalistic and overly technical’. Similarly in Bovis Lend Lease v The Trustees of the London Clinic (2009)48 Akenhead J said it is important to distinguish between the dispute that has crystallized and the evidence provided to support or contest it, which may legitimately change as the dispute develops.

3.38 However, it remains a matter of fact as to whether a dispute has crystallized and this also applies to whether an additional claim can be added onto an existing dispute or whether it needs to crystallize. In Beck Interiors Ltd v UK Flooring Contractors Ltd (2012)49 Beck claimed damages for repudiation against a subcontractor. In a letter served after close of business on the day before Good Friday they added a claim for delay and liquidated damages. They served an adjudication notice on the first working day after Easter. UK Flooring asserted there was no jurisdiction in relation to the liquidated damages claim as that dispute had not crystallized. The TCC judge agreed and accordingly the liquidated damages claim was severed from the rest of the adjudication decision, and not enforced.50