Section 107 and the Requirement for Writing

SECTION 107 AND THE REQUIREMENT FOR WRITING

Relevance of s. 107 to Contracts with Written Submissions Adjudication Agreements | |

(3) Implied Terms, Variations, and Other Non-written Agreements | |

(1) The 1996 and the 2009 Acts

2.01 Section107(1) of the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (the ‘1996 Act’) states that ‘The provisions of this Part apply only where the construction contract is in writing, and any other agreement between the parties as to any matter is effective for the purposes of this Part only if in writing.’1 Accordingly this requirement is a precondition for the application of the other provisions of Part II of the Act, and as such it is one of the gateways into Part II along with ss. 104 and 105.

2.02 In its origin s. 107 of the 1996 Act was an attempt to enforce the construction industry to submit to a standard form of contract. That did not succeed. However the requirement for writing was maintained because writing provides certainty. Certainty was thought to be important in the context of the adjudication process which is a summary procedure to be undertaken under a demanding short timetable. The requirement that the contract be in writing means the adjudicator who is obliged to decide a dispute arising under a contract within a rapid timeframe starts with some certainty as to what the terms of the contract actually are.

2.03 However s. 107 gave rise to jurisdictional arguments thought by some to undermine expeditious and effective adjudication of disputes. Where a contract is not recorded in writing, unless there is an express agreement to adjudicate a dispute, there is no right to adjudicate as s. 108 of the 1996 Act will not apply. Accordingly, in the past respondents have been able to rely on the absence of writing to defeat the adjudication process. Jurisdiction arguments based on s. 107 have been deployed during the adjudication, during enforcement proceedings, and sometimes have been subject of pre-emptive declaratory relief actions.

2.04 Against this background it may not be surprising that s. 107 has been repealed by s. 139 of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (the ‘2009 Act’). Accordingly contracts entered into after the 2009 Act came into force will no longer need to be evidenced in writing in order for the other provisions of the 1996 and 2009 Acts to apply.2

2.05 This chapter therefore considers the law as it applies to contracts entered into before the 2009 Act came into effect. There is no shortage of judicial decisions on the meaning and effect of s. 107 as can be seen from the Tables of Cases set out in this chapter. Most of the cases concern enforcement applications at which the defendant challenged the validity of an adjudicator’s decision on the ground that it was made without jurisdiction because the contract did not satisfy s. 107. In that context therefore the judicial consideration of s. 107 has frequently been from the perspective of an application for summary judgment. It is important to remember when reading these authorities that at a summary judgment application the defendant does not have to prove that it is right but needs only to show that its arguments have a reasonable prospect of success and therefore need to be tried fully. This means that at a summary judgment application to enforce an adjudicator’s decision, where the defendant has been able to show that there is a triable issue concerning whether a contract was concluded, summary enforcement of the adjudicator’s decisions have failed.3 When this happens the court’s judgment about the enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision is deferred until after the full trial of those issues regarding the formation of contract. Effectively this can mean the intended summary enforcement of the adjudicator’s decisions is frustrated.

2.06 However the repeal of s. 107 will not necessarily remedy that problem. Without the requirement for writing more agreements will be brought within the sphere of operation of the 1996 Act (as amended by the 2009 Act) and potentially this means more adjudications. However, because the existence of an agreement within the meaning of ss. 104 and 105 remains a gateway into the statute, a defendant may still argue that no such contract was in fact concluded. If the contract relied on by the referring party was made orally, then the court at the enforcement hearing will likely be asked to decide if any oral contract was ever concluded. A dispute based on oral testimony is usually unsuitable for summary judgment and may be deferred to full trial where oral evidence may be given. In other words, whilst the removal of the requirement for writing may bring more contracts within the Act, it is foreseeable that summary enforcement of decisions based on those non-written agreements may prove difficult.

2.07 Having said that, the consequence of the matter proceeding to a full trial need not lead to significant delay to enforcement. The issues regarding oral agreements may be limited and can be tried relatively quickly, or as a preliminary issue. The Technology and Construction division of the High Court will usually aim to give directions to ensure the jurisdiction issue which cannot be determined summarily will nevertheless be tried quickly.

Relevance of s. 107 to Contracts with Adjudication Agreements

2.08 There is an important distinction between contracts that incorporate express adjudication provisions and those construction contracts that do not. In a contract with an express adjudication clause the availability of adjudication as a mechanism for interim dispute resolution does not depend on s. 107 of the Act but on the terms of the adjudication agreement (subject to the proviso that in a contract governed by the Act where the adjudication clause fails to comply with s. 108, the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’) will replace the agreed provision4). In principle therefore a construction contract with an express adjudication agreement may be varied orally and the oral variation need not satisfy s. 107 and a dispute thereunder may be the subject of a contractual adjudication as long as it falls within the scope of the adjudication agreement.5

(2) Section 107 and the Requirement for Writing

2.09 Prior to its amendment in 2009 the provisions of Part II of the 1996 Act applied only where the construction contract was in writing, and only where ‘any other agreement between the parties as to any matter’ was in writing. As discussed below, the interpretation of s. 107 gave rise to a fairly large body of case law concerning what constitutes an agreement in writing for the purpose of s. 107, what constitutes writing and how much of the agreement needs to be evidenced in writing.

Section 107(2): What Constitutes an Agreement in Writing?

2.10 There are three categories described in s. 107(2) where the agreement is to be treated as being in writing. The first is where the agreement itself is made in writing (whether signed by the parties or not).6 This contemplates a written document containing the agreement itself. The second is where an agreement is made by communications in writing.7 In other words the offer, acceptance and terms are set out in correspondence between the parties. The third category is where the agreement is evidenced in writing.8 This latter provision has given rise to some difficulties regarding what consists of evidence in writing and whether the whole or part of the agreement must be evidenced in writing.

What Is Writing?

2.11 References in Part II of the 1996 Act to anything being written or in writing include its being recorded by any means.9 There are no reported cases on this provision but it is suggested this will include drawings and may also include tape recordings of agreements.

What Must Be Evidenced in Writing?

2.12 It is the terms and not merely the existence of a construction contract which must be evidenced in writing. Ex post facto evidence of the existence of an agreement will be insufficient for the purposes of s. 107 of the Act (unless the parties can rely on s.107(5), as discussed below). In RJT Consulting Engineers Ltd v DM Engineering (Northern Ireland) Ltd (2002) (Key Case)10 the Court of Appeal were divided over whether the whole of the agreement needs to be in writing or whether it is sufficient for those material terms relevant to the issues in the adjudication to be in writing. The majority of the Court of the Appeal gave a literal interpretation to the Act holding that ‘what has to be evidenced in writing is, literally, the agreement, which means all of it, not a part of it’ (per Ward LJ at paragraph 19). The reasoning was based not just on the wording of the statutory provisions themselves, which require ‘the agreement’ to be in writing, but also on policy grounds. It was said that disputes about oral agreements are not readily susceptible to resolution by a summary procedure such as adjudication, because the written agreement is the foundation from which a dispute may spring and the least the adjudicator has to be certain about is the terms of the agreement which are giving rise to the dispute.

2.13 Auld LJ, expressing the minority view, considered that it was the material terms which needed to be in writing. He feared that jurisdictional wrangling on this issue would clog the adjudicative process and defeat the purpose of the Act.

2.14 For a short time after the decision in RJT Consulting Engineers there was some doubt as to the weight to be given to the minority reasoning of Auld LJ.11 Since then however, that the High Court is bound by the majority view was unequivocally stated by Jackson J in Trustees of Stratfield Saye Estate v AHL Construction Ltd (2004):12 ‘In my view, it is not possible to regard the reasoning of Auld LJ as some kind of gloss upon or amplification of the reasoning of the majority. The reasoning of Auld LJ, attractive though it is, does not form part of the ratio of RJT.’ The overwhelming majority of cases have followed this approach, applying the test that all the terms must be in writing or evidenced in writing.

2.15 Regarding minor or trivial matters, Ward LJ left the door very slightly ajar when he said: ‘No doubt adjudicators will be robust in excluding the trivial from the ambit of the agreement and the matter must be entrusted to their common sense.’13 In this context it has been suggested that an item may be considered trivial or minor if, considered objectively, it is not a material term of the contract and therefore falls within the category of items with which an adjudicator should deal robustly.14

Acceptance by Conduct

2.16 Despite the requirement in s. 107(1) that ‘any agreement between the parties as to any matter’ is effective only if in writing, the courts do not seem to have had a problem allowing acceptance by conduct, as was the case in Trustees of Stratfield Saye Estate v AHL Construction Ltd (2004).15 In that case the judge found that all the terms that had been negotiated between the parties had been recorded in writing thus satisfying the test laid down by the Court of Appeal in RJT Consulting16 for compliance with s. 107(2)(c). Similarly in Dean and Dyball Construction Ltd v Kenneth Grubb Associates Ltd (2003)17 and confirmed in Durham County Council v Jeremy Kendall (2011)18 the courts have considered acceptance by conduct sufficient for a s. 107 compliant contract to exist. Acceptance by conduct is also probably valid pursuant to s. 107(3) as an agreement other than in writing by reference to terms that are in writing.

Incorporation of Terms

2.17 Once it is established that the adjudicator has jurisdiction, a question about whether a particular term has or has not been incorporated into an agreement is a matter which the adjudicator has power to decide:

Thus so long as it is established or agreed that there is a contract in existence between the parties, [and] that it is a construction contract … any other dispute as to the terms of the construction contract is as much a dispute arising under the contract as would be a dispute as to the working through of any terms to the valuation machinery.19

2.18 If however the incorporation argument is really a question about an oral agreement of a term of the contract which has not been evidenced by writing, that is a s. 107 matter which goes to jurisdiction.

Section 107(3): The Effect of Referring to Terms in Writing

2.19 Where parties agree otherwise than in writing by reference to terms which are in writing, they make an agreement in writing (s. 107(3)). In Carillion Construction Ltd v Devonport Royal Dockyard (2002)20 Carillion argued that the oral agreement made reference to the existing written contract which was sufficient for the purpose of s. 107(3). Judge Bowsher rejected that argument. In that case the variation in question was a change to the payment terms, from contractually defined ‘Actual Cost’ plus a fee and a gainshare arrangement, to a cost-reimbursable basis. The judge relied on the fact that s. 107(3) uses the words ‘by reference to terms that are in writing’ and not ‘by reference to a previous agreement that is in writing’. The judge said that if oral variations were brought within the 1996 Act purely because they referred to the original written contract, the intent of the Act, that adjudicators would not have to decide on the existence and terms of oral agreements, would be defeated. Accordingly he found that a fundamental variation to a construction contract made orally and without writing was outside the Act and takes the entire contract outside the ambit of the Act.

2.20 Judge Bowsher found that it is necessary for any oral agreement itself to be evidenced by the written terms referred to.21 The judge postulated that this would include a verbal agreement in relation to a draft written contract which had already been prepared. It could also cover an oral agreement that the terms of a standard form contract will apply.

Section 107(4): Oral Agreement Recorded with Authority

2.21 An oral agreement recorded by one party, or by a third party, with the authority of the parties will constitute an agreement evidenced in writing for the purpose of the s. 107.22 This provision does not stipulate the only method by which an agreement may be evidenced in writing23 and s. 107(6) provides that reference to anything being written includes it being recorded by any means.

Section 107(5): Exchange of Written Submissions

2.22 An exchange of written submissions in adjudication proceedings or in arbitral or legal proceedings in which the existence of an agreement otherwise than in writing is alleged by one party against another party and not denied by the other party in his response, constitutes, as between those parties, an agreement in writing to the alleged effect. Section 107(5) provides the only exception to the general requirement of s. 107 that all the agreement must be evidenced in writing.24

2.23 The Departmental Advisory Committee (DAC) report on the equivalent provision in the Arbitration Act provided some useful guidance about the effect of s. 107(5):

(a) The provision operates to create a form of statutory estoppel where one party admits the existence of an arbitration clause in its response document. This is equivalent to an ad hoc conferral of jurisdiction onto the arbitrator.

(b) Interestingly, if there is no response served at all there is no statutory estoppel created by silence.

(c) The DAC report on the Arbitration Act advised that not every written response would comprise a submission for the purpose of the section, only formal submissions would suffice.

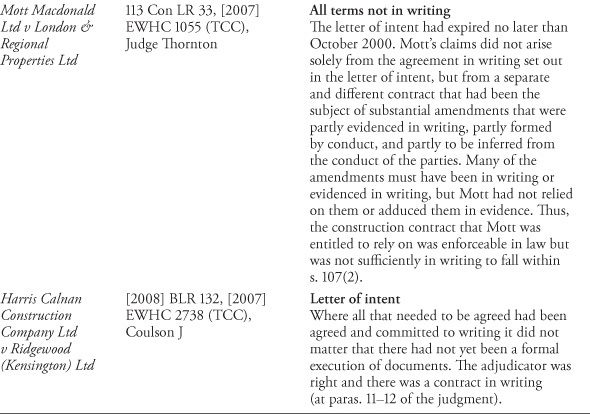

2.24 The last four words of the provision are important. The exchange constitutes an agreement in writing which does more than evidence the existence of the agreement. It also evidences the effect of the agreement alleged and that must mean it evidences the terms of the contract material to the purposes of that particular adjudication. This was the conclusion of the TCC judge in Grovedeck Ltd v Capital Demolition Ltd (2000).25 It was also the conclusion of Judge Thornton in Mott MacDonald Ltd v London & Regional Properties Ltd (2007).26 In that case the respondent admitted an agreement existed, but contended it was a different agreement from the one alleged by the referring party and was not fully evidenced in writing. On the facts the judge decided there had been no effective admission because the respondent continued to allege the contract failed to comply with s. 107. These cases suggest that s. 107(5) only applies where the terms of the agreement have also been admitted.27

2.25 Section 107(5) would prevent a defendant who had accepted that there was a written construction contract in the adjudication from subsequently arguing at the enforcement hearing that no written agreement existed. This is a relatively straightforward proposition consistent with the common law rules of estoppel and those authorities that deal with the conferral of jurisdiction.28

2.26 It is not clear whether s. 107(5) is intended to remove from a party the right to challenge jurisdiction on the ground that the contract, whilst admitted, was not one that was in writing.29 The judge in Grovedeck decided that s. 107(5) cannot have been intended to have that effect and concluded that s. 107(5) applied only to oral agreements that had been admitted in other preceding adjudications.

2.27 The opposite view was expressed in ALE Heavy Lift v MSD (Darlington) Ltd (2006).30 The claimant’s referral notice cited a contract evidenced in writing by a letter and its enclosures. The response alleged the contract incorporated oral agreements that were referred to in the letter. The respondent therefore did not deny the contract in the referral notice and did not take a jurisdiction point that the contract was part oral. There had been no denial of jurisdiction and so on the facts of the case the judge decided that any challenge to jurisdiction had been waived. However, in dealing with the claimant’s additional argument that as a matter of statute there was also jurisdiction pursuant to s. 107(5) Judge Toulmin said:

88. If I had to disagree with His Honour Judge Bowsher Q.C’s interpretation of section 107 (5) of the Act in Grovedeck I would do so, but I simply need to follow Ward LJ’s proposition in paragraph 19 of his judgment that where the material relevant parts of a contract alleged in the written submissions in the adjudication are not denied, that is sufficient. That applies both to submissions relating to an alleged written agreement as well as submissions relating to an alleged oral agreement. If I have to take this route I conclude that applying the Statute the Adjudicator had jurisdiction. The simple answer is that as a matter of contract where the jurisdiction of the Adjudicator is not challenged on a particular ground, a challenge of jurisdiction on that ground has been waived, and the parties have agreed to proceed with the adjudication despite the possibility of that challenge.

2.28 The Court of Appeal in RJT Consulting Engineers expressly chose not to rule on the judge’s finding in Grovedeck (at paragraph 16 of the judgment). In Trustees of Stratfield Saye Estate v AHL Construction Ltd (2004)31 Jackson J decided that the existence of a s. 107 compliant contract had been admitted by the Estate in two out of three adjudications and so the contractor was entitled to rely on this pursuant to s. 107(5) of the Act. Similarly in SG South Ltd v Swan Yard (Cirencester) Ltd (2010)32 the TCC judge also found that s. 107(5) applied to admissions made in the submissions in the adjudication itself.33

2.29 The judge in ALE Heavy Lift did not consider whether his interpretation of the statute would apply even where there had been a denial of jurisdiction and reservation of rights by the defendant. This point and this provision remain to be considered by an appellate court.

2.30 Although there have been a great many cases on whether the requirement for writing has been satisfied, almost all turned on the facts of the individual contractual negotiations between the parties. As far as a statement of principle goes, there is really only one authority for the proposition that all the terms of the agreement need to be evidenced in writing.