Secret Trusts, Half-Secret Trusts and Mutual Wills

Chapter 11

Secret Trusts, Half-Secret Trusts and Mutual Wills

Chapter Contents

Secret Trusts and Half-Secret Trusts

As You Read

Look out for the following key points:

the definition of a secret trust, a half-secret trust and how they differ from each other;

the definition of a secret trust, a half-secret trust and how they differ from each other;

the rationale underpinning the court’s enforcement of secret and half-secret trusts; and

the rationale underpinning the court’s enforcement of secret and half-secret trusts; and

the concept of mutual wills and the notion that they are based on an agreement formed between the testators that the survivor should not alter their will after the first one of them has died.

the concept of mutual wills and the notion that they are based on an agreement formed between the testators that the survivor should not alter their will after the first one of them has died.

Secret Trusts and Half-Secret Trusts

Definition

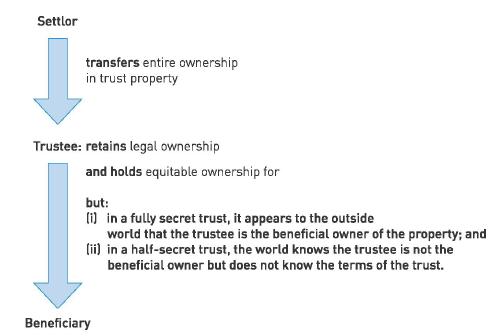

A secret trust is a trust of which there is, prima facie, no evidence of its existence in a testator’s will. The secret trust is probably an example of an express trust although there is debate (both judicial and academic) about whether it might be a constructive trust. It appears, on a reading of the relevant clause in the will, that property has simply been given to the recipient and that they are both the legal and beneficial owner of it. Unbeknown to readers of the will, however, the recipient is not the beneficial owner of it. Instead, he will have been asked by the testator (obviously before the testator’s death) to hold the property on trust for the real beneficiary. In that manner, a trust will be formed of the property after the testator dies. The recipient will own the legal title and the ‘real’ beneficiary will enjoy the equitable interest. A trust will have been formed by the testator but its existence will be kept secret from the world at large. Sometimes these trusts are known as ‘fully’ secret trusts, in part to differentiate them from ‘half’-secret trusts.

A half-secret trust is similar to a fully secret trust. The difference is that whilst there is absolutely no clue in the testator’s will that a fully secret trust has been formed, there is a giveaway that the testator has declared a half-secret trust. A half-secret trust gives an indication that the property is subject to a trust by using the words ‘on trust’ or similar. What remains secret are the terms of the trust. Consequently, a reader of a will where a half-secret trust has been declared knows that the recipient is a trustee but does not know who the true beneficiary is or any other terms of the trust.

Both types of secret trust are illustrated using the now-familiar diagram in Figure 11.1.

Background: Scandal in the law of trusts!

Fully and half-secret trusts appear in wills. Section 9 of the Wills Act 1837 provides that no will can be valid unless it is in writing, signed by the testator and witnessed by at least two witnesses present at the same time.1 After the testator has died, the will usually becomes a

public document, which any member of the public may inspect. This means that the contents of a testator’s will become available for the world at large to read.

As will become clear, a number of the early cases on secret trusts revolved around a testator wishing to make provision in his will for his mistress and/or illegitimate offspring. Leaving property as a gift or declaring a trust in the will would have meant that the testator’s wife and family would have immediately become aware of the existence of the testator’s mistress and illegitimate children. Thus testators began to use the mechanism of a secret trust to conceal the true beneficiary of their generosity in their will. The testator would commonly provide the detail of the trust in a separate document to their will or even sometimes in oral instructions to the trustee. The latter is sometimes referred to as ‘parol evidence’.

The difficulty with the terms of secret trusts being contained in parol evidence is, however, that they run contrary to the principle of transparency and openness enshrined in s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 that all terms of a will should be in writing and that the will usually becomes a document available to the public for their inspection after the testator’s death. It is this conflict that the courts have wrestled with from the nineteenth century when wills containing secret trusts first became prevalent.2

Fully Secret Trusts

Requirements

The requirements for the validity of a fully secret trust were set out by Brightman J in Ottaway v Norman.3 He said that it must be shown that:

[b]the testator communicated that intention to the recipient; and

[c]the recipient accepted the testator’s intention. The recipient’s acceptance of that obligation could be either express or implied by acquiescence.

First requirement: An intention to impose an obligation on the recipient that the property should be held on trust for the true beneficiary

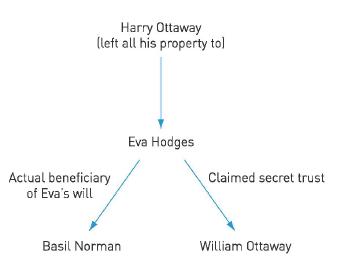

The facts of Ottaway v Norman showed that all three requirements for a valid trust were met. The facts are summarised in Figure 11.2.

Harry Ottaway wrote his will in 1960, in which he left his bungalow in Cambridgeshire together with its contents to his partner, Miss Eva Hodges, with whom he had lived for nearly 30 years. Harry died in 1963. Eva died five years later, having left the bungalow and the contents to the defendant, Mr Basil Norman. Harry’s son, William Ottaway, brought an action claiming a declaration that the house and its contents were rightfully his. The legal basis of his action was that his father had told Eva on a number of occasions that he wanted the bungalow and its contents to go to William on her death. Eva was to have the property for her life but thereafter it should go to William. William said that Eva had accepted this obligation by never disagreeing with Harry’s intention. Eva’s first will had indeed contained a provision leaving the bungalow and its contents to William. She made a later will in 1967, however, leaving the bungalow and the contents to Basil. The difficulty for William (as with all claimants alleging the existence of a secret trust) was that it appeared on the face of Eva’s will that Basil was the true and rightful recipient of the bungalow and its contents. William’s action was, therefore, based on the existence of a secret trust founded on the conversations between Harry and Eva.

Having heard the evidence, Brightman J found that Harry had established a secret trust in William’s favour. Harry had intended that Eva give the bungalow and its contents to William after her death, he had communicated that intention to her and that she had accepted that intention.

Brightman J also made other important points concerning secret trusts:

[b] it was not necessary for the establishment of a fully secret trust to show that the recipient had been guilty of committing a deliberate wrong in denying the existence of the trust. There was no evidence that Eva had purposefully sought to defraud William of his entitlement. She simply made an alternate will due to a friendship she had formed with Basil after Harry’s death.

William’s second claim for money which his father had left Eva, allegedly for her use during her lifetime and thereafter for William, failed. Brightman J was prepared to accept, without deciding as such, that in theory a secret trust could be created of property for the recipient to use during her lifetime with remainder of it being left to the true beneficiary. He thought that such a trust would be suspensory in effect during the recipient’s life and would activate itself on her death. But such a trust could not be established on the evidence. It failed the test for certainty of subject matter as it was not clear quite how much money was supposed to be left for William after Eva’s death and to fulfil such certainty, Eva would have had to keep an amount separate from her own money during her lifetime. Such unascertainable amounts infringed the principle of certainty of subject matter and could not create a valid trust. Whilst it is possible to have a secret trust of an asset that would inevitably be wasted by the recipient, the settlor must make the precise subject matter of the trust categorically clear.

Making connections

Remember from Chapter 5 that all express trusts must fulfil the three certainties: of intention, subject matter and object. Certainty of subject matter requires that it must always be clear what the nature and extent of the trust property is. If this is not clear, the trust will fail.

The facts of Ottaway v Norman demonstrated that the testator possessed an intention to subject the recipient to an obligation in favour of the true beneficiary. The other criteria to form a valid trust of communicating that intention to the recipient and the recipient accepting that obligation are no less important. All three criteria must be present for a secret trust to be established.

Ultimately, though, a secret trust is a type of express trust and the requirements needed to form a valid express trust must all be fulfilled. Specifically the three certainties must be satisfied for, as Megarry V-C said in Re Snowden:4

The more uncertain the terms of the obligation, the more likely it is to be a moral obligation rather than a trust: many a moral obligation is far too indefinite to be enforceable as a trust.

This dictum is a salutory reminder that all secret trusts must comply with the necessary ingredients to declare an express trust.

Second requirement: The testator must communicate his intention to the recipient

The testator must clearly place the recipient of their property under a binding obligation to hold that property on trust for the true beneficiary. There must be no doubt that the testator communicates their instructions to the trustee. The controversial issue is when such communication must occur.

It seems not to matter whether the testator communicates his intention to the trustee either before or after he makes his will. This was spelt out by Lord Warrington of Clyffe in Blackwell v Blackwell5 when he said, ‘it is immaterial whether the trust is communicated and accepted before or after the execution of the will’.6

Arguably, it is tidier if the testator can communicate his intention to establish a secret trust with the recipient of that information as trustee before he executes his will. In that way, the testator can be sure, when signing his will, that he has a trustee in place. But it seems that, alternatively, the testator can communicate his intention to create a secret trust after he has executed his will. The reason given by Lord Warrington for this was that, in the worst case scenario, if the testator communicates his intention after he has executed his will and the trustee declines to accept the terms of the trust and administer it, the option always remains open to the testator to write another will, disposing of his property in a different manner or by a secret trust with a different trustee.

What seems to be clear, however, is that the testator must communicate his intention to the trustee during his lifetime and that communication must include the terms of the trust in it. The testator cannot communicate the terms of the trust to the trustee after his (the testator’s) death, as occurred in Re Boyes.7

George Boyes wrote his will in London in June 1880. On the face of the document, he left everything to his solicitor, Mr Carritt, absolutely. George died two years later, in Ghent (Belgium). Mr Carritt’s evidence was that during the writing of the will, George had made it clear to him that he was not to take the property absolutely, but was instead to hold the property on trust, the terms of which George would make clear in a letter which he would send to Mr Carritt when he arrived in Europe. Mr Carritt said that he accepted the trusteeship.

No letter was ever sent to Mr Carritt but after George’s death, two near-identical letters were found in his personal belongings. Both letters said that his property was to be held on trust by Mr Carritt for George’s mistress, Nell Brown. The issue for the High Court was whether this secret trust had been validly declared.

Kay J held that the trust had not been validly declared. There had been no valid communication of its terms — specifically, who the objects of the trust were — during the lifetime of the testator. What the testator had done in writing the two letters was effectively to leave further wills, or codicils (documents which amend part of a will), which did not comply with the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Such a trust could not be allowed to be valid as it would go against the policy of s 9 which required all wills and codicils to be validly witnessed. There was no trust in favour of Nell in the case. Instead, Mr Carritt held George’s property on trust for George’s next-of-kin, as if he had died intestate.

Glossary: Codicil

A codicil is a supplementary document that amends a will. It must comply with the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Codicils were useful in pre-word processor days, as they enabled a testator to amend his will quickly without the need to rewrite the entire will. They are used much less often nowadays as it is often just as quick to amend the will on a computer and reprint the entire document.

Can the terms of the secret trust be constructively communicated by the testator to the trustee?

In Re Keen,8 the issue was whether valid communication had taken place during the testator’s lifetime by a trustee being in possession of an envelope sealed by the testator which contained details of the terms of the trust.

The facts concerned the will of Harry Keen. He wrote his will in 1932, leaving £10,000 on trust to his trustees, on terms which were to be notified by him to his trustees during his lifetime. No mention of the beneficiary’s details were contained in the will. Mr Keen, however, had written a separate memorandum, in which he had set out the details of the beneficiary — a lady whom he knew. He handed the memorandum, which was in a sealed envelope, to one of his trustees. The trustee only opened the envelope after Mr Keen’s death. The issue for the court was whether Mr Keen had successfully created a valid secret trust. (In fact, this was a case concerning a half-secret trust as Mr Keen had made it apparent from his will that the £10,000 was being left on trust.)

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal held that there was no valid secret trust, but they did so for different reasons.

In the High Court, Farwell J held that Mr Keen had failed to notify the trustees of the intended beneficiary of the trust during his lifetime, as he had promised to do in the clause in his will. Leaving a note which was read only after his death did not constitute notifying the trustees of the beneficiary during his lifetime. No trust of the money could be established. As the trust failed, the money had to fall into Mr Keen’s residuary estate.

In the Court of Appeal, Lord Wright MR thought that Farwell J’s view of Mr Keen’s failure to notify the trustees of the intended beneficiary during his lifetime took a far too narrow view of what ‘notifying’ meant. He said that by holding the beneficiary’s details in a sealed envelope, the trustees had the ‘means of knowledge available [to administer the trust] when it became necessary and proper to open the envelope’.9 He gave a vivid example for which his judgment is famous: ‘[t]o take a parallel, a ship which sails under sealed orders, is sailing under orders though the exact terms are not ascertained by the captain till later.’10

It could not be disputed that the ship sailing under sealed orders had been validly despatched and, in the same manner, the trust could still be successfully administered by the trustee when the time came to do so.

But Mr Keen’s trust still failed. The primary reason was that while he had ‘notified’ the trustee of his chosen beneficiary, the means of his notification contravened s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. The notification by Mr Keen was not correctly drafted according to the requirements of s 9 and neither was it witnessed. He had merely left a letter which, whilst signed by him, had not been witnessed. Mr Keen was not at liberty effectively to reserve to himself a power to circumvent the requirements of s 9, which his letter did.

Communication of the terms of the trust to the trustees can occur either before or after the will is written, but they must be consistent with the precise wording of the will.

Does the testator have to communicate his intention to all of his trustees, or will just some of them suffice? The answers to this question were summarised by Farwell J in Re Stead:11

[b] If the testator makes a fully secret trust by giving property to two trustees to hold as tenants in common but only one promised to hold the property on trust, the other trustee is not bound by the trust and can take their share of the property absolutely; and

[b] If the testator makes a fully secret trust by giving the property to two trustees to hold as joint tenants, whether both trustees are bound by the trust depends on whether the fully secret trust was made in response to a prior promise by the trustees to administer the trust:

If yes, both trustees will be bound to administer the trust; but

If no, only the trustee making the promise is bound to administer the trust. The other trustee may take his share of the property beneficially for himself.

Third requirement: The trustee must accept their obligation to administer the trust

As with any express trust, the trustee must accept their trusteeship. If it cannot be shown that they have accepted their trusteeship, there will be no trust. Acceptance of trustee obligations can be either express or implied. Implied acceptance, according to Lord Westbury in McCormick v Grogan, 12 may be ‘by any mode of action which the disponee knows must give to the testator the impression and belief that he fully assents to the request’.

An example of trustees not accepting their obligations was shown in Wallgrave v Tebbs.13 The facts concerned the will of William Coles who by his will made in 1850, left £12,000 to Messrs Tebbs and Martin together with freehold lands and houses in Chelsea and Kensington, London. The will seemed to leave the property to Messrs Tebbs and Martin absolutely. After Mr Coles‘ death, however, it was claimed that it was not Mr Coles’ intention that they should enjoy the property themselves, but instead that they should hold it on trust for charitable purposes. Their reply to that was they had never had any such communication with Mr Coles. They said that they had understood from Mr Coles‘ solicitor who prepared the will that he had left them the property because he knew one of them personally and the other by reputation as being interested in religious and charitable causes. Mr Coles simply presumed that if he left them money they would use it for such purposes. In addition, Mr Coles had set out his thoughts on this basis in a letter written by Mr Coles’ solicitor to Messrs Tebbs and Martin but Mr Coles had never signed it.

They said that they were sympathetic to Mr Coles‘ wishes but denied that there was a formal trust of the property in existence for such purposes. Their view was that Mr Coles had not communicated his views to them before his death and they had not accepted the alleged trust.

The Vice-Chancellor, Sir W Page Wood, accepted that Messrs Tebbs and Martin knew nothing about Mr Coles‘ wishes until after his death. No communication of the terms of the trust had occurred by Mr Coles and no acceptance of that trust had similarly taken place. Both ingredients were needed if a trust was to be found. No trust was established and Messrs Tebbs and Martin took the property for themselves absolutely.

This decision must surely be right because the office of trusteeship is onerous. It is not equitable if it is enforced upon someone who has known nothing about the prospect of becoming a trustee until after the testator’s death, when it is too late to object to it. A trustee must agree to their role voluntarily. Messrs Tebbs and Martin were denied that opportunity and it was right that no trust was created.

Can the property be increased in a secret trust?

This issue was addressed by the Court of Appeal in Re Colin Cooper.14 Colin Cooper wrote a will, leaving £5,000 on a half-secret trust. His trustees accepted the trust. He then went on a big-game shooting holiday to South Africa, but contracted a fatal illness. Shortly before his death, he wrote another will, puporting to increase the amount left on trust to £10,000. His trustees did not know about this increase, so were never given the chance to accept their new obligation.

The Court of Appeal held that the increase was void. The key ingredients for a valid secret trust of communication to the trustees and agreement by them to administer the trust were only made in relation to the initial £5,000. The trustees had only ever been given the chance of agreeing to administer a trust for £5,000. A trust for double the sum needed their consent.

Sir Wilfred Green MR, obiter, thought that no consent from the trustees would be needed if:

[a] the testator increased the sum to be left on trust by such a small amount (‘de minimis’) that the increase would really make no difference to the trustees administering the trust; or

[b] if the testator in fact left a lower amount to the trustees to administer than he had set out in his trust. Their consent to the greater amount would, by definition, mean that they had agreed to administer a trust up to that sum.

Although the decision concerned a half-secret trust, the judgment of the Court of Appeal was not limited to these types of secret trust and so can apply equally to fully secret trusts.

The rationale underpinning why secret trusts are enforced: Fraud vs the ‘dehors’ the will theories

The cases thus far have shown a desire by testators to set up a trust by using a separate document to convey its terms to the trustees. Sometimes the testator might instead wish to communicate the terms of the trust to the trustees orally as opposed to in writing. But whether the communication is oral or written, the difficulty is the same: unless there is a written document, signed by the testator and duly witnessed by at least two witnesses, s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 will not have have been fulfilled. The prima facie conclusion from this is that any trust which is set out by the testator orally or in a document which does not comply with s 9 is that it cannot be valid. And yet, as has been shown in Ottaway v Norman, such trusts are valid. The reason why equity will recognise such a trust was first explained by the House of Lords in McCormick v Grogan.15

The facts concerned the will of Abraham Craig. He contracted cholera and, on his death-bed, sent for his friend, Mr Grogan, the defendant. He explained to Mr Grogan that he had left all of his property to him. Mr Grogan was to find his will in a desk with a letter with it. Mr Craig never asked for agreement from Mr Grogan to the letter or its contents.

After Mr Craig’s death, Mr Grogan found the will and the letter. The letter contained a long list of friends and relatives to whom Mr Craig wanted his money to be left. It contained the following words towards the end:

I do not wish you to act strictly as to the foregoing instructions, but leave it entirely to your own good judgment to do as you think I would if living, and as the parties are deserving, and as it is not my wish that you should say anything about this document there cannot be any fault found with you by any of the parties should you not act in strict accordance with it.

Mr Grogan made a number of payments to some of the individuals named in the letter. But he declined to make a payment to others, one of whom was the claimant in the case. James McCormick brought an action claiming that Mr Craig had established a trust in his letter and that, as such, Mr Grogan was obliged to pay him the £10 per year for the rest of his life that Mr Craig had awarded him.

The Irish court of first instance declared that the letter did give rise to a trust binding on Mr Grogan. The Court of Appeal in Chancery in Ireland reversed that decision. Mr McCormick appealed to the House of Lords. The House of Lords held that there was no trust on the facts of the case. All Mr Craig had done was to leave a guide for Mr Grogan as to what he should do with the property. The very words used by Mr Craig, giving Mr Grogan freedom and discretion over the choice of the ultimate recipients of the property, showed that he was not imposing any form of obligation on Mr Grogan to distribute the property to particular individuals or a class of them.

What is interesting, though, is that the House of Lords discussed the rationale underpin-ning secret trusts. Lord Westbury explained that a court of equity would enforce a secret trust due to the maxim that equity would not allow a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. If a trustee denied that a trust existed simply because the testator had not complied with the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837, equity would intervene to recognise the trust.

Making connections

The rationale underpinning the recognition of secret trusts as explained in McCormick v Grogan is the maxim that equity will not allow a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. An executor cannot, therefore, hide behind the Wills Act 1837 and refuse to recognise a secret trust, that he voluntarily accepted to administer, before the testator died. Such a response would be to rely on the strict letter of the Wills Act 1837 to the detriment of the testator’s true intentions for their property. Equity will not permit this to occur.

This maxim also underpins equity’s recognition of an oral declaration of a trust of land which is prima facie contrary to the requirements of s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925, as shown in Rouchefoucauld v Boustead.16 See Chapter 4 where this topic is discussed.