RESTRUCTURING, RESCUING TROUBLED COMPANIES AND TAKEOVERS

Restructuring, rescuing troubled companies and takeovers

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should understand:

When section 110 schemes of reconstruction are available and when they are typically used

When section 110 schemes of reconstruction are available and when they are typically used

When Part 26 schemes of arrangement are available and when they are typically used

When Part 26 schemes of arrangement are available and when they are typically used

The object and effect of a company voluntary arrangement (CVA) and the procedure to put one in place

The object and effect of a company voluntary arrangement (CVA) and the procedure to put one in place

The availability, object and effect of a small company moratorium

The availability, object and effect of a small company moratorium

The objectives of administration

The objectives of administration

How administrators are appointed, the effect of administration and how administration comes to an end

How administrators are appointed, the effect of administration and how administration comes to an end

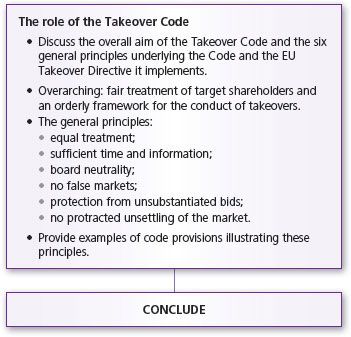

The role and scope of application of the Code on Takeovers and Mergers (‘the City Code’)

The role and scope of application of the Code on Takeovers and Mergers (‘the City Code’)

The role and legal status of the Panel on Takeovers and Mergers (‘the Panel’)

The role and legal status of the Panel on Takeovers and Mergers (‘the Panel’)

The laws and statutory procedures covered in this chapter are relevant to a number of very different practical situations in which companies or corporate groups find themselves. These situations may be grouped under three headings:

Mergers and acquisitions (sometimes called takeovers) of companies where a change of control occurs.

Mergers and acquisitions (sometimes called takeovers) of companies where a change of control occurs.

Restructuring, including demerging, a financially healthy company or corporate group where no change of control occurs.

Restructuring, including demerging, a financially healthy company or corporate group where no change of control occurs.

Corporate rescue activity where a company is in financial difficulty.

Corporate rescue activity where a company is in financial difficulty.

These activities frequently involve making changes to the company’s shareholdings, to its debt or both. In this chapter we refer to such changes as ‘restructuring’ the company or corporate group.

Also, a number of legal options may be available to a company in a given situation which must select the procedure best suited to its circumstances and aims. Consider a company in financial difficulty the debt of which needs to be restructured to avoid insolvent liquidation. Depending upon how co-operative its creditors are and how complex the required restructuring of the debt is, the company may simply pursue renegotiation with its creditors or it may use one or a combination of: the company voluntary arrangement procedure in Pt I of the Insolvency Act 1986, the Part 26 scheme of arrangement procedure in the Companies Act 2006 and the administration procedure in Pt II and Sched B1 of the Insolvency Act 1986.

Another example is a basically healthy company wishing to sell one of its businesses. Here, although a straightforward business sale agreement may suffice, commercial and tax advantages are often secured by using a section 110 scheme of reconstruction, sometimes called a ‘demerger’ scheme, or, in complex cases, a Part 26 scheme of arrangement may be used.

The terminology used in relation to restructuring can be confusing and a word of warning is appropriate. Terms are often used in a practical sense, without the need to focus on legal significance, resulting in terms being used that connote a range of different legal activities. ‘Merger’ and ‘takeover’ are examples of this. Some of the terms used in statutory provisions relevant to this chapter are also unclear in meaning and scope. For example, whilst the legal meaning of the composite term ‘reconstructions and amalgamations’ can be established from s 900 of the Companies Act 2006, what constitutes a reconstruction distinct from an amalgamation is not legally clear cut.

A by-product of the uneasy fit of the law with practical situations is the absence of a broadly agreed upon structure for presenting the law and statutory procedures covered in this chapter. Bearing in mind the comments above and as this chapter provides an outline only of the relevant law and legal procedures, a structure that begins with the law has been adopted and the material covered in this chapter is organised into four sections as follows: schemes of arrangement and reconstruction, CVAs and small company moratora, administration and takeovers.

15.2 Schemes of arrangement and reconstruction

In this section we examine two key statutory procedures by which the structure of a company or a group of companies may be changed, or restructured, schemes of arrangement under Part 26 of the Companies Act 2006 and schemes of reconstruction, also known as demerger schemes, under the simpler Insolvency Act 1986 s 110 procedure. The emphasis is on restructuring of the shareholdings of a company or corporate group, rather than simply debt restructuring.

We have already considered in Chapters 7 and 8 processes by which the rights attached to particular shares may be varied and the share capital of a company increased and decreased and, in the final section of this chapter, we consider the legal framework governing changes of control, or ‘takeovers’. The statutory processes considered in this section are used where the processes considered in Chapters 7 and 8, or a takeover bid, are not available, the requirements are too cumbersome, the conditions are unlikely to be fulfilled or there is other good reason to choose one of the statutory schemes. Tax considerations are extremely important in restructuring activity and may lead to a restructuring proposal that can only be achieved using one legal process rather than another.

15.2.1 Section 110 schemes of reconstruction

Availability and usage

The most common use of s 110 of the Insolvency Act 1986, known as a section 110 scheme of reconstruction or a ‘demerger scheme’, is by a company wishing to separate out one or more of its businesses. The demerger may be a preliminary step in the sale of one or more of its businesses to another company or it may be part of an internal reconstruction of a corporate group designed to deliver commercial and tax advantages. For example, demergers can be used to unlock shareholder value, that is, to overcome the strict rules on maintenance of capital so that shareholders can lawfully receive capital from the company.

Demergers can be achieved by a number of routes. The tax benefits of using a section 110 scheme of reconstruction, coupled with the greater expense and longer timeframe for putting a Part 26 scheme of arrangement in place, make section 110 schemes very attractive. Section 110 cannot, however, be used if a compromise is sought with creditors: a Part 26 scheme of arrangement or a voluntary arrangement is required to achieve such a compromise.

A section 110 scheme necessarily entails the winding up of the original, transferor company. Do not be misled by this into thinking that it is therefore a corporate rescue procedure. Section 110 is designed for use where the company is solvent and applies only to a company that is being voluntarily wound up.

A typical section 110 demerger is effected by the company transferring its assets to two (or more) newly created companies in return for shares in those companies. The shares in the new companies are distributed to the shareholders of the original, now parent, company in proportion to their shareholdings in the original company and the original company is then wound up. The shareholders may continue to own the two companies or one of them may be sold off.

The section 110 procedure

The procedure to put a section 110 scheme in place is to hold a general meeting at which the following special resolutions are proposed (although private companies can use the written resolution procedure):

to wind up the company (a members’ voluntary winding up);

to wind up the company (a members’ voluntary winding up);

to appoint a liquidator;

to appoint a liquidator;

to approve a section 110 scheme of reconstruction;

to approve a section 110 scheme of reconstruction;

to authorise the liquidator to enter into and carry out the section 110 scheme of reconstruction.

to authorise the liquidator to enter into and carry out the section 110 scheme of reconstruction.

Following the passing of the resolutions, and subject to the rights of dissenting shareholders, the scheme is binding on all members of the company (s 110(5)) and the merger can be effected in accordance with the reconstruction agreement.

Dissenting shareholder protection

If any shareholder does not vote in favour of the section 110 scheme, s 111 gives him the right to require the liquidator to buy out his shares. The liquidator should therefore also be authorised by resolution at the general meeting to buy out shareholders pursuant to s 111 and the manner by which the liquidator may raise money to do so must be stated in the authorising resolution. In addition to providing for a dissenting shareholder to insist on being bought out, s 111 provides for a shareholder to stop a scheme going forward by giving notice to the liquidator to abstain from carrying the resolution into effect. A shareholder cannot be deprived of the rights afforded by s 111 by a provision in the company’s articles of association (Payne v The Cork Company Ltd [1900] 1 Ch 308).

Creditor protection

A creditor of the company who is unhappy with a scheme may have negotiated contractual provisions in its loan agreements that are triggered by such a reconstruction. In the absence of such contractual or ‘self-help’ remedies, the only route available to a creditor to stop a section 110 scheme from progressing is to petition the court for a compulsory winding-up order. To secure a winding-up order a creditor must demonstrate either that it is just and equitable to wind up the company or that the company is unable to pay its debts (as that phrase is defined in s 123 of the Insolvency Act 1986). Even if one of these grounds can be established, the decision to order a winding up or not is in the discretion of the court (s 122). If a court orders the company to be wound up within a year of the special resolution authorising a section 110 scheme, the special resolution is not valid unless sanctioned (approved) by the court (s 110(6)).

Steps can be taken to significantly reduce the risk of a special resolution authorising a section 110 scheme of reconstruction being (i) stopped by a dissenting shareholder or (ii) rendered invalid by a court-ordered winding up within a year of its passage. One commonly adopted step is to incorporate a new ‘holding’ company (‘holdco’) to own the company (or parent company of the group) to be reconstructed. Holdco issues its own shares to the shareholders of the company in return for their shares in the company. It is Holdco that then enters into voluntary winding up and effects a section 110 scheme. Holdco has no creditors which virtually removes the risk of a court-ordered winding up. The s 110 special resolution can be passed more than seven days before a winding-up resolution so that the shareholder dissent period has expired before the winding up commences.

scheme of arrangement procedure

The statutory procedure set out in Pt 26 of the Companies Act 2006 which facilitates changes being made to the rights of creditors or shareholders without securing the unanimous approval of those affected by the changes

15.2.2 Part 26 schemes of arrangement

Availability and usage

The statutory procedure set out in Pt 26 of the Companies Act 2006, called the ‘scheme of arrangement’ procedure, exists to facilitate changes being made to the rights of creditors, shareholders or both without securing the unanimous approval of those affected by the changes. Section 895 states that Part 26 applies where a compromise or arrangement is proposed between a company and its creditors, or any class of them, and its members, or any class or them. Accordingly, a Part 26 scheme of arrangement can be used:

to restructure debt, with or without changes to shareholdings; or

to restructure debt, with or without changes to shareholdings; or

to restructure the rights of shareholders, with or without changes to the rights of creditors.

to restructure the rights of shareholders, with or without changes to the rights of creditors.

If a Part 26 scheme of arrangement is to be used to effect a compromise by the company and its creditors and/or its shareholders of any rights and liabilities between them, there must be an accommodation by each side. A unilateral release of rights by one group, for example, is not a compromise and will not amount to an arrangement therefore cannot be achieved by a Part 26 scheme of arrangement (Re Savoy Hotel Ltd [1981] 3 All ER 346, Re NFU Development Trust Ltd [1973] 1 All ER 135). Where such a release is part of a wider arrangement, however, such as the release of claims against one company in return for the substitution of claims against a new company, the procedure can be used (In the matter of Bluebrook Ltd [2009] EWHC 2114 (Ch)).

An arrangement involving a change in who the shareholders are, but no change in the rights of those shareholders or any creditors (such as a takeover), whilst not a compromise, can be an arrangement for Part 26 purposes (Re T & N Ltd (No 3) [2007] 1 BCLC 563). In Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (in Administration) (No 2) [2009] EWCA Civ 1161, the Court of Appeal held that, as a matter of statutory construction, an arrangement between a company and its creditors within Part 26 means an arrangement dealing with their rights inter se as a debtor and creditor. Accordingly, whilst an arrangement could extend to the rights of creditors in the company’s property held by creditors merely as security, the court had no jurisdiction under Part 26 to sanction a scheme to release rights held by a company under a trust for the benefit of creditors as the proprietary claim of the creditors was not a claim in respect of a debt or liability.

The procedure for a Part 26 scheme of arrangement to be put in place is cumbersome and consequently expensive and slow resulting in its use being confined to complex restructurings or situations where no other procedure is available. That said, Part 26 schemes of arrangement are regularly used in all three of the non-winding-up situations identified in the introduction to this section:

mergers and acquisitions (sometimes called takeovers) of companies where a change of control occurs;

mergers and acquisitions (sometimes called takeovers) of companies where a change of control occurs;

restructuring, including demerging, a financially healthy company or corporate group;

restructuring, including demerging, a financially healthy company or corporate group;

corporate rescue activity where a company is in financial difficulty.

corporate rescue activity where a company is in financial difficulty.

Taking each of these in turn, first, Part 26 schemes are regularly used to effect takeovers, including takeovers of companies with shares listed on a stock exchange such as the London Stock Exchange. In fact, they have become the most favoured method by which to structure a takeover of a company with listed shares. Where a private sale or acquisition is negotiated, a Part 26 scheme may be used to effect a reconstruction to merge or demerge companies and businesses and bring about other changes to improve the commercial benefits of the sale or acquisition, including effectively managing the tax implications.

Second, examples of when a Part 26 scheme of arrangement might be used to restructure a financially healthy company are:

to return capital to shareholders;

to return capital to shareholders;

to divide or demerge a company (typically a family owned company) when a founder member or other large shareholder dies or retires;

to divide or demerge a company (typically a family owned company) when a founder member or other large shareholder dies or retires;

in anticipation of a disposal, that is, all or a part of the company or group being taken over or sold to a third party;

in anticipation of a disposal, that is, all or a part of the company or group being taken over or sold to a third party;

in anticipation of an acquisition of a company or business by the company or group.

in anticipation of an acquisition of a company or business by the company or group.

Turning finally to use of Part 26 schemes of arrangement by companies in financial difficulty, Part 26 is not restricted to compromises with creditors before a company becomes subject to a formal rescue or winding-up procedure. Administrators can also use the Part 26 scheme of arrangement procedure within the context of an administration as can liquidators in the course of a winding up, although use of Part 26 by the liquidator of a company in involuntary liquidation is rare.

The Part 26 procedure

The Part 26 procedure involves two applications to court, one before and one after the summoning of separate meetings of those classes of creditors and shareholders who would be affected were the proposed scheme of arrangement to be implemented.

The first stage in the procedure is an application to the court, usually by the company or the administrator, for an order that meetings be summoned of every affected class of shareholders and creditors for the purpose of securing approval of the proposed scheme (s 896(1)). The fairness of the scheme is not considered at this stage (Re Hawk Insurance Company Ltd [1922] 2 Ch 723). The court may, however, decide not to order the meetings, if, for example, it considers there is such a level of opposition to the scheme that the scheme would not be approved by the shareholders or creditors as the case may be (Re Savoy Hotel Limited [1981] Ch 351).

The court-ordered meetings must then be summoned. The scheme of arrangement must be approved by a majority in number, representing 75 per cent in value of the class of creditors or shareholders, as the case may be, voting, either in person or by proxy, at the duly summoned meeting (s 899(1)). Only if approved by this majority at each of the court-ordered meetings can the court sanction, i.e. approve, the scheme.

Identification of the different classes of shareholders and creditors, that is, recognising when a sub-group of shareholders or creditors needs to be regarded as unique and therefore a separate class and accorded a separate meeting is often an area of difficulty in relation to Part 26 schemes. The case law in which this issue is raised is extensive. If a sub-group feels it ought to have a separate meeting, and convinces the court of this, the court will not sanction the scheme without the requisite majority approval by that sub-group at a separate meeting.

The test to determine whether a sub-group is a separate class or not for the purposes of what is now Part 26 was stated by Bowen LJ in Sovereign Life Assurance Co v Dodd [1892] 2 QB 573:

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘What is the proper construction of [the] statute? It makes the majority of the creditors or of a class of creditors bind the minority; it exercises a most formidable compulsion upon dissentient, or would-be dissentient, creditors; and it therefore requires to be construed with care, so as not to place in the hands of some of the creditors the means and opportunity of forcing dissentients to do that which it is unreasonable to require them to do, or of making a mere jest of the interests of the minority. … The word “class” is vague, and to find out what is meant by it we must look at the scope of the section, which is a section enabling the Court to order a meeting of a class of creditors to be called. It seems plain that we must give such a meaning to the term “class” as will prevent the section being so worked as to result in confiscation and injustice, and that it must be confined to those persons whose rights are not so dissimilar as to make it impossible for them to consult together with a view to their common interest.’ | |

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘In exercising its power of sanction … the Court will see: First, that the provisions of the statute have been complied with. Secondly, that the class was fairly represented by those who attended the meeting and that the statutory majority are acting bona fide and are not coercing the minority in order to promote interests adverse to those of the class whom they purport to represent, and, thirdly, that the arrangement is such as a man of business would reasonably approve.’ | |

If a Part 26 procedural requirement has not been satisfied, the court will not sanction the scheme. Also, if a reduction in capital is a feature of the scheme, the further legal procedures governing capital reduction must be complied with (ss 641, 645–653) and a court will not sanction a scheme where they have not been complied with. Note, however, that if the court has, by oversight, sanctioned a scheme that involves an unlawful capital reduction, the scheme will not be invalidated on this ground (British & Commonwealth Holdings Ltd v Barclays Bank [1996] 1 WLR 1).

The test to be applied to determine the reasonableness of the approval was stated by Maugham J in Re Dorman Long & Co Ltd [1934] 1 Ch 635:

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘[The court must be satisfied that] the proposal is such that an intelligent and honest man, a member of the class concerned, acting in respect of his interests might reasonably approve [the scheme].’ | |

The role of the court is not to substitute its judgment for that of the requisite majority and courts have endorsed the words in Buckley on the Companies Acts, that ‘the court will be slow to differ from the meeting’. The key concern of the court is to be satisfied that the shareholders and creditors have acted in good faith and that the majority has voted in a class meeting to promote their interests as members of that class, rather than to promote other interests, such as to promote their interests as members of a different class of shareholders, or, possibly, their interests as creditors (Carruth v ICI 1937] AC 707).

A court order sanctioning the scheme has no effect until a copy has been delivered to the registrar of companies (s 899(4)). When the order takes effect it is binding on all creditors, shareholders and the company (or, as appropriate, the administrator, liquidator and all contributories of the company) (s 899(3)).

Section 900 reconstructions and amalgamations

Section 900 extends the powers of the court on a Part 26 application by empowering the court to order a broad range of matters, either by including them in the order approving the scheme of arrangement or in a separate order. The broader powers are available and may be exercised by the court only when a Part 26 scheme of arrangement:

includes or is connected with a scheme of reconstruction of any company or companies or the amalgamation of any two or more companies; and

includes or is connected with a scheme of reconstruction of any company or companies or the amalgamation of any two or more companies; and

Examples of matters the court may order under s 900 include:

the transfer of the business or undertaking (including liabilities) of one company to another;

the transfer of the business or undertaking (including liabilities) of one company to another;

the allotting of shares or debentures of one company to another person;

the allotting of shares or debentures of one company to another person;

that legal claims against a company be continued against the company to whom the business is being transferred;

that legal claims against a company be continued against the company to whom the business is being transferred;

the dissolution of a company without a winding up.

the dissolution of a company without a winding up.

Part 27 and the Cross Border Merger Regulations

Where an application under Part 26 involves a ‘merger or division’, as that term is defined for the purpose, additional requirements are imposed before a scheme of arrangement can be sanctioned. If the merger or division involves a public company rather than a private company, the requirements are set out in Pt 27 and, where the ‘merger or division’ involves either public or private companies in more than one member state, the additional requirements are set out in the Companies (Cross Border Merger) Regulations 2007 (SI 2007/2974) (as amended by the Companies (Reporting Requirements in Mergers and Divisions) Regulations 2011 (SI 2011/1606)). These provisions are of limited practical relevance in the UK where virtually all mergers and divisions of companies are structured such that they do not fall within the scope of application of the EU-inspired rules.

15.3 Company voluntary arrangements (CVA) and small company moratoria

This section is relevant to companies in financial difficulties. When a company experiences financial difficulty it may struggle to ‘service its debt’, that is, make interest payments, capital repayments and/or meet certain covenants, or conditions, specified in its loan agreements. The situation may deteriorate rapidly into one in which there is no reasonable prospect that the company can avoid going into insolvent liquidation, or in which an individual creditor considers it has no option but to seek a winding-up order.

It is important that directors and officers of companies understand the options available to facilitate a ‘corporate rescue’, i.e. the procedures that can be utilised to allow a breathing space to take stock of the situation and to restructure the company’s debt (and, sometimes, the shareholder arrangements) to give the company or group the best chance to trade its way back to financial good health.

The law and procedures outlined in this section (CVAs and the small company moratorium) and the following section (administration) are designed to facilitate restructuring of the rights of creditors and, sometimes, shareholders of a company in financial difficulties. They are governed by the Insolvency Act 1986 and the Insolvency Rules 1986 (both as extensively amended). The general approach to corporate insolvency has changed since the 1986 Act was first enacted, resulting in the law being changed both to facilitate corporate rescue and to make the law operate more fairly in relation to unsecured creditors. These changes were made principally by the Insolvency Act 2000 and the Enterprise Act 2002.

CVAs could be more popular if a moratorium, i.e. a period in which no creditor could bring proceedings to enforce a debt, or put the company into administration or liquidation, were available for a period to enable the CVA to be agreed and put in place. Such a moratorium is available to small companies, although the procedure for putting a CVA in place for a small company seeking a moratorium, considered at section 15.3.2, is cumbersome and, consequently, not very popular. Government proposals put forward in 2011 to enable all companies to apply for a court-sanctioned moratorium (a standalone restructuring moratorium) when proposing a CVA have not been implemented but it has been reported (in summer 2014) that the government has indicated that it will be reviewing its earlier consultation. To allow a company to enjoy protection from its creditors whilst remaining under the control of its directors, rather than an independent officer such as an administrator or liquidator, would be a significant step in insolvency law and it has been suggested that the availability of such moratoria could inhibit rather than facilitate corporate rescue.

company voluntary arrangement (CVA)

A composition in satisfaction of a company’s debts, or a scheme of arrangement of its affairs, that binds all affected company creditors even though not all of them agree to its terms, entered into in accordance with the procedure in Pt 1 of the Insolvency Act 1986

15.3.1 Company voluntary arrangements

Part 1 of the Insolvency Act 1986 contains a procedure by which a company may put in place a composition in satisfaction of its debts, or a scheme of arrangement of its affairs, that binds all affected unsecured company creditors even though not all of them agree to its terms. Note, however, that secured creditors must agree in order to be bound (s 4(3)), and no modification to the right of preferential creditors may be made without their consent (s 4(4)). The proposal, approval and implementation of such a composition or scheme, called a company voluntary arrangement (CVA), must comply with ss 1–7. A CVA proposal may be made to the company and its creditors either by its directors (s 1(1)) or by the administrator or liquidator of the company (s 1(3)).

A CVA proposal must provide for a nominee, who must be a qualified insolvency practitioner and is called a supervisor, to supervise its implementation (s 1(2)). If the CVA is proposed by the directors, they must give the supervisor (i) notice of the CVA proposal setting out its terms and (ii) a statement of affairs of the company (which will give details of its creditors, debts, other liabilities and assets) (s 2(3)). Within 28 days of such notice the supervisor must submit a report to the court (s 2(2)) stating:

whether, in his opinion, the proposed CVA ‘has a reasonable prospect of being approved and implemented’;

whether, in his opinion, the proposed CVA ‘has a reasonable prospect of being approved and implemented’;

whether, in his opinion, meetings of the company and its creditors should be summoned to consider the proposal; and

whether, in his opinion, meetings of the company and its creditors should be summoned to consider the proposal; and

proposed dates, times and places for such meetings.

proposed dates, times and places for such meetings.

Assuming the supervisor’s report is positive, and unless the court directs otherwise, the meetings are then summoned by the supervisor to consider the proposal. Every creditor of the company of whose claims and address the supervisor is aware must be invited to the creditors’ meeting (s 3(3)) and all meetings must be conducted in accordance with the Insolvency Rules 1986. At the creditors’ meeting, the proposal must be approved by a majority of three-quarters or more in value of creditors present (in person or by proxy). The outcome of each meeting must be reported to the court by the chairman of the meeting and notices of the result given in accordance with the Insolvency Rules 1986.

The shareholders and creditors may decide to approve the proposed CVA with or without amendments. The CVA takes effect if the proposal is approved at both the shareholders’ meeting and the creditors’ meeting. If it is approved only at the meeting of the creditors, or there is a difference in what is approved by the shareholders and what is approved by the creditors, the CVA takes effect as approved by the creditors subject to the right of a member, within 28 days, to make an application to court whereupon the court may make such order as it thinks fit (s 4A).

Any shareholder or creditor who believes that the CVA unfairly prejudices the interests of a creditor or shareholder or that there has been some material irregularity at or in relation to one or more meetings, may, within 28 days, apply to the court for an order revising or revoking the CVA or directing a further meeting or meetings (s 6).

The CVA binds all creditors of the company as if they were parties to it (s 5), and creditors cannot commence legal proceedings to enforce a debt owing to them unless the company fails to perform the CVA. During the implementation of the CVA, either the supervisor or a person dissatisfied with his actions may apply to court and the court may make such order as it thinks fit (s 7).

Example

By CVA, a company agrees to pay £100,000 per year for each of three years to the supervisor for distribution to creditors. If the company fails to pay the agreed sum to the supervisor or the CVA has in some other way not been implemented in accordance with its terms, the CVA is deemed to have come to an end (s 7B). On the CVA coming to an end, the company becomes liable to the creditor for any sum that had been payable under the CVA but was not in fact paid.

15.3.2 The small company moratorium

A procedure allowing small companies to obtain a stay or moratorium in the enforcement of its debts to give it time to put a CVA in place was introduced into the Insolvency Act 1986 by the Insolvency Act 2000. The procedure, set out in detail in Sched A1 to the 1986 Act, is only available to the directors of a company. It is not relevant to an administrator or liquidator (they do not need it).

The procedure is available only to directors of small companies defined to be those companies satisfying two out of three of the following conditions (from s 382(3) Companies Act 2006 (as amended)):

Turnover | not more than £6.5 million |

Balance sheet total | Balance sheet total not more than £3.26 million |

Employees | Employees not more than 50 employees |

The procedure cannot be used if it has been used in the previous 12 months.

The directors send a document setting out the terms of the proposed CVA and a statement of the company’s affairs to the nominee of the proposed CVA and the moratorium comes into force when the directors file the following documents with the court:

document setting out the terms of the proposed CVA;

document setting out the terms of the proposed CVA;

statement of the company’s affairs;

statement of the company’s affairs;

statement that the company is eligible for a moratorium;

statement that the company is eligible for a moratorium;

statement from the nominee that he has given his consent to act;

statement from the nominee that he has given his consent to act;

statement from the nominee that in his opinion:

statement from the nominee that in his opinion:

the proposed CVA ‘has a reasonable prospect of being approved and implemented’,

the proposed CVA ‘has a reasonable prospect of being approved and implemented’,

the company is likely to have sufficient funds available to it during the proposed moratorium to enable it to carry on its business, and

the company is likely to have sufficient funds available to it during the proposed moratorium to enable it to carry on its business, and

meetings of the company and its creditors should be summoned to consider the CVA proposal.

meetings of the company and its creditors should be summoned to consider the CVA proposal.

When the moratorium comes into effect, the directors must notify the nominee who is required to advertise the moratorium and notify the registrar, the company and any creditor who has petitioned for the winding up of the company (Sched A1, paras 9 and 10).

A moratorium initially lasts for no more than 28 days. An extension of up to a further two months may be approved by meetings of the shareholders and creditors during that initial period.

A moratorium ends on the day on which the meeting of shareholders or creditors (whichever is later) is held at which the proposed CVA is approved. If meetings of the shareholders and creditors have not been summoned, the moratorium will end on the expiry of the initial period. The nominee must advertise the coming to an end of a moratorium and notify the court, the registrar, the company and any petitioning creditor.

administrator

An insolvency practitioner appointed by the court under an administration order or by the company, its directors or the holder of a qualifying floating charge, the principal objective of whom is to rescue the company as a going concern