Religious harassment

Chapter 6

Religious harassment

General background

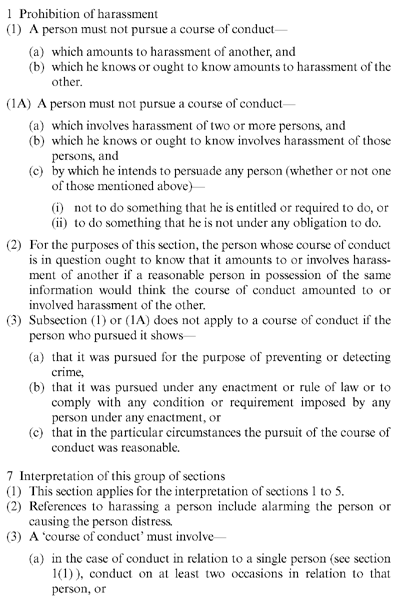

There are two main ways in which harassment on the grounds of religion is dealt with by the law. Where there is religious harassment of an employee in connection with their employment then a claim can be brought under reg 5 of the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations 2003; in all other cases a claim can be brought under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997.

When the government initially introduced the Equality Bill into Parliament, cl 47 of the Bill proposed a general tort of religious harassment, based on reg 5; cl 47 was, however, removed by the House of Lords and the government accepted the removal. It was common ground in the debate on cl 47 that all forms of religious harassment could already be dealt with by means of a claim for damages and/or an injunction, under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 and for that reason both reg 5 and the 1997 Act are considered in this chapter.

Claims of harassment contrary to reg 5 must be brought in the employment tribunal within three months of the last incident of harassment complained of (see Chapter 4 for tribunal procedure); civil claims under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 can be brought in either the High Court or the county court and must be brought within six years of the last incident of harassment complained of (s 6 of the Act); criminal charges under s 2 of the Act must be brought within six months of the last incident of harassment complained of: DPP v Baker [2004] EWHC 2782 (Admin).

Regulation 5

When the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations 2003 were brought into force, the concept of harassment in the workplace had been well established for a number of years. Racial harassment was recognised as being contrary to the Race Relations Act 1976 and sexual harassment as contrary to the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. However, though the phrases ‘racial harassment’ and ‘sexual harassment’ have been widely used in cases under these Acts, there was, until 2003, no specific definition of harassment in either of the two acts. Claims alleging harassment were brought under s 6(2)(b) of the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 or s 4(2)(c) of the Race Relations Act 1976, both of which prohibited employers from subjecting employees to discrimination or to ‘any other detriment’. Harassing behaviour was regarded by courts and tribunals to be behaviour which constituted a ‘detriment’.

Throughout the EU sexual harassment at work was dealt with differently by the laws in each Member State and this was considered by some to be undesirable. Therefore, as part of its goal to ensure common working standards throughout the EU, the following definition of harassment was adopted by the EU in Council Directive 2002/73/EC and EU Council Directive 2000/78/EC:

Unwanted conduct with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person and of creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

It was decided by the British Government to adopt this definition virtually unchanged as the definition of harassment for all forms of discrimination. The only significant change being that, in place of the EU wording ‘and of creating’ the UK definition is ‘or of creating’; the government taking the view that it was impossible to conceive of a situation where harassment occurred which violated the dignity of a person but which did not create an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment. Whether that view is correct is perhaps debatable, but the new definition must be considered on its own merits, since reg 2(3) states that ‘ “detriment” does not include harassment within the meaning of regulation 5’; therefore, claims of religious harassment in the workplace must be brought under reg 5 and cannot be claimed as ‘harassment and/or detriment’. For reasons which seem diffcult to understand, the government did not adopt the new definition of harassment on the same date for all forms of discrimination but instead introduced it for racial harassment on 19 July 2003 in the Race Relations Act 1976 (Amendment Regulations) 2003 SI 2003/1626, for disability harassment on 1 October 2004 in the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (Amendment) Regulation 2003 SI 2003/1673, and for sexual harassment on 1 October 2005 in the Employment Equality (Sex Discrimination) Regulations 2005 SI 2005/2467, whilst reg 5 of the Employment Equality (Religion of Belief) Regulations 2003 came into force on 2 December 2003. Because of the adoption of this new statutory definition of harassment, old cases where tribunals decided that particular types of behaviour did not constitute sexual or racial harassment should be approached with caution and may well be overruled by the new definition of harassment. However, it does seem that behaviour which would have been considered as harassment under the ‘any other detriment’ case law will continue to be regarded as harassment under the new statutory definition.

Requirements of reg 5

(1) For the purposes of these Regulations, a person (‘A’) subjects another person (‘B’) to harassment where, on grounds of religion or belief, A engages in unwanted conduct which has the purpose or effect of—

(a) violating B’s dignity; or

(b) creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for B.

(2) Conduct shall be regarded as having the effect specified in paragraph (1)(a) or (b) only if, having regard to all the circumstances, including in particular the perception of B, it should reasonably be considered as having that effect.

Therefore, in order for conduct by A to constitute harassment it must either:

(a) have the purpose of violating B’s dignity; or

(b) have the purpose of creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for B; or

(c) have the effect of violating B’s dignity; or

(d) have the effect of creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for B.

In order to prove a claim of religious harassment contrary to reg 5, the alleged harasser (A) must engage in ‘unwanted conduct’ and must do so ‘on grounds of religion or belief’. Whether conduct is unwanted will be a matter of fact for a tribunal to determine but, for example, if employees are engaging in mutual banter about religion, it may be rather diffcult for one employee who is participating in that banter suddenly to take offence at a particular thing that is said and to claim that as harassment unless what was said was so beyond the bounds of the general banter that it could be considered as clearly unwanted. Whether conduct is unwanted is usually a question of fact varying from case to case; if someone asks that particular behaviour should stop then it is obvious that the conduct is ‘unwanted’ from that moment on, but it is not essential that the victim state that they dislike particular behaviour in order for it to be unwanted; a degree of common sense must be applied. In Reed v Stedman [1999] IRLR 299, where the defendant made a sexually suggestive remark and attempted to look up the complainant’s skirt, the Employment Appeal Tribunal said (at para 30):

… it seems to be the argument that because the Code [the ACAS Code] refers to ‘unwanted conduct’ it cannot be said that a single act can ever amount to harassment because until done and rejected it cannot be said that the conduct is ‘unwanted’. We regard this argument as specious. If it were correct it would mean that a man was always entitled to argue that every act of harassment was different from the first and that he was testing to see if it was unwanted; in other words it would amount to a licence for harassment … The word ‘unwanted’ is essentially the same as ‘unwelcome’ or ‘uninvited’. No one other than a person used to engaging in loutish behaviour could think that the remark made in this case was other than obviously unwanted.

Similarly, in Heads v Insitu Cleaning Co [1995] IRLR 4, when a women employee was greeted with the words ‘Hiya, big tits’ as she walked into a meeting, that remark was accepted as being obviously unwanted.

Therefore, if a Mormon employee was to be greeted each day with the words ‘Oh God it’s holy Joe Smith’ or ‘are you wearing your temple undies today’, then that type of behaviour would constitute ‘unwanted’ conduct without the victim needing to object to it first. But evidence of mutual banter, or the fact that an exchange was initiated by the alleged victim, might mean that remarks which would otherwise constitute harassment would not be harassment in that particular situation. For example, if a religious member of staff said that he was going on pilgrimage to ‘pray for all you sinners’ then a response ‘don’t bother praying for me, religion is just a load of rubbish’ would probably not constitute harassment even though it might be regarded as an unnecessarily aggressive response.

Secondly, the unwanted conduct must be engaged in by A ‘on the grounds of religion or belief’. It is unclear from the wording of reg 5 whether the conduct must be on the grounds of religion or belief of A himself or on the grounds of religion or belief of B, but para 1.4 of the ACAS guidelines on the regulations (Appendix C–2) indicate that reg 5 could cover either situation. The ACAS guidelines also consider that reg 5 covers harassment directed not just at the religion or belief of the victim but also at the religion or belief of any person with whom the victim associates and it is likely that tribunals will agree with and adopt the wide-ranging ACAS definition which is consistent with the way other types of discrimination law have been interpreted. Provided that the harassment is on ‘on the grounds of religion or belief’, it will be irrelevant whether it is on the grounds of religion or belief of A, or of B or of someone with whom B associates.

It is, however, essential that the conduct is engaged in by A ‘on the grounds of religion or belief’. Merely because A engages in conduct to which B objects ‘on the grounds of religion or belief’, that will not be suffcient to constitute harassment of B contrary to reg 5 unless the conduct is engaged in by A ‘on the grounds of religion or belief’. For example, there have been media reports that some workplaces have been telling staff to remove mugs which contain pictures of pigs and not to have any items on their desk etc. which relate to pigs, the reason for these instructions being concern that such references to pigs might harass Muslims; however, it is doubtful whether employers can justify such instructions if the mugs etc. are not introduced for the purpose of causing harassment to Muslims etc. but are merely personal items which the employee has with them anyway. If a new employee, who is Muslim, starts in an offce and one of their co-workers then brings in a mug with a pig picture on it or puts a model of a pig on their desk, then it might not be too diffcult to establish that such behaviour was done ‘for the purpose’ of ‘creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment’ for the Muslim employee. However, if a co-worker merely happens to possess a pig mug or model because, for example, they bought it on a visit to a farm or nature reserve or it was given to them by a son or daughter and has sentimental value, then there is no reason why they should be asked to remove it. The mug etc. is not in their possession ‘on grounds of religion or belief’ and therefore cannot constitute harassment, albeit that a Muslim worker, for their own personal reasons, might find it offensive. Similarly, a display of the St George flag might be objected to by some Muslims on the basis that it is a ‘Crusaders’ flag but if the St George flag is being displayed for reasons of patriotism or, more probably, out of support for the England football team, then it is not being displayed ‘on grounds of religion or belief’ and therefore would not constitute harassment under reg 5.

For the purpose of reg 5 it is irrelevant whether the person doing the harassment is a member of the same religion as the victim of the harassment. For example, two women, A and B, work in a Catholic book shop. Wherever she can, B goes to a Catholic church where there is a celebration of the Tridentine (traditional Latin) Catholic Mass, whilst A goes only to churches where the Mass is in the new modern form in English, and A makes regular sarcastic comments to B about ‘out of date’ Catholics hanging on to ‘mumbo jumbo Latin’. Even though both A and B are members of the same religion, A would still be guilty of harassment of B because her comments would be made ‘on grounds of religion or belief’.

Where the conduct complained of is engaged in with the ‘purpose’ of violating dignity etc., then that should be capable of proof through evidence of the actions or words of A. For example, if Muslim employee B had stated in a conversation with co-worker A that, for religious reasons, B found pictures of pigs offensive and the next day A put a picture of a pig on his desk, then that might well be good evidence that A put the picture on his desk with ‘the purpose’ of ‘creating an offensive environment’ for B. Similarly, if a Christian employee was to ask his colleagues to stop using the words ‘Jesus Christ’ as a swear word in his presence and they did not stop doing so, then it would seem likely that they were engaging in that conduct ‘for the purpose’ of creating an offensive environment for their Christian colleague.

Where a tribunal is satisfied that particular behaviour was engaged in for ‘the purpose’ of causing harassment then that will usually be suffcient to prove the case. More diffcult problems arise where the harassment has the ‘effect’ of violating dignity etc. but it is not proved that that was its ‘purpose’. When this is the situation, tribunals and employers will have to consider reg 5(2):

(2) Conduct shall be regarded as having the effect specified in paragraph (1)(a) or (b) only if, having regard to all the circumstances, including in particular the perception of B, it should reasonably be considered as having that effect.

Regulation 5(2) therefore requires tribunals to apply an objective ‘reasonableness’ test to allegations that conduct has had the ‘effect’ of violating dignity etc. It is, however, a reasonableness test that is somewhat skewed in favour of the subjective point of view of the victim. Questions will arise over the clause that the tribunal should have regard to all the circumstances including ‘in particular the perception of B’. Does ‘in particular’ mean that the perception of B overrides other circumstances and other points of view? The proper interpretation of reg 5(2) would seem to be that the perception of B is merely one of the factors that a tribunal must have regard to, even though it is clearly a very important factor; if all other factors are equal, then the perception of B becomes the dominant fact on which the tribunal should base its decision but the perception of B cannot override all other circumstances. Therefore, if A is doing something which is in accordance with his own religion, and is otherwise lawful, then even though B may dislike those actions, that would not be suffcient for them to qualify as harassment. For example, if A is a Muslim woman who wears a niqab (a veil covering the lower part of her face) then many of her fellow workers may find that offensive but that would not mean that the wearing of the niqab constituted harassment. As Baroness Hale said in Begum v Denbigh High School [2006] UKHL 15, para 96:

… the sight of a woman in full purdah may offend some people, and especially those western feminists who believe that it is a symbol of her oppression, but that could not be a good reason for prohibiting her from wearing it.

In determining whether behaviour is reasonable a tribunal should have regard to the judgment of the EAT in Driskel v Peninsular Business Services Ltd