Registered and Unregistered Land

Introduction – what is registered land?

Prior to 1925, the seller proved their right to sell their land to the buyer by exhibiting to them a series of linked documents showing how the property had passed down from one owner to another over a set period of time, ending with them as seller. This was known as a ‘chain of title’.

However, due to a number of inherent flaws in the unregistered conveyancing process (detailed below), the decision was taken to make wholesale change to the way in which the transfer and ownership of land was undertaken and documented. This was finally achieved by the Land Registration Act 1925, which introduced a new centralised system of land registration throughout England and Wales. ‘Registered land’ is land that has been registered under this system.

Aim Higher

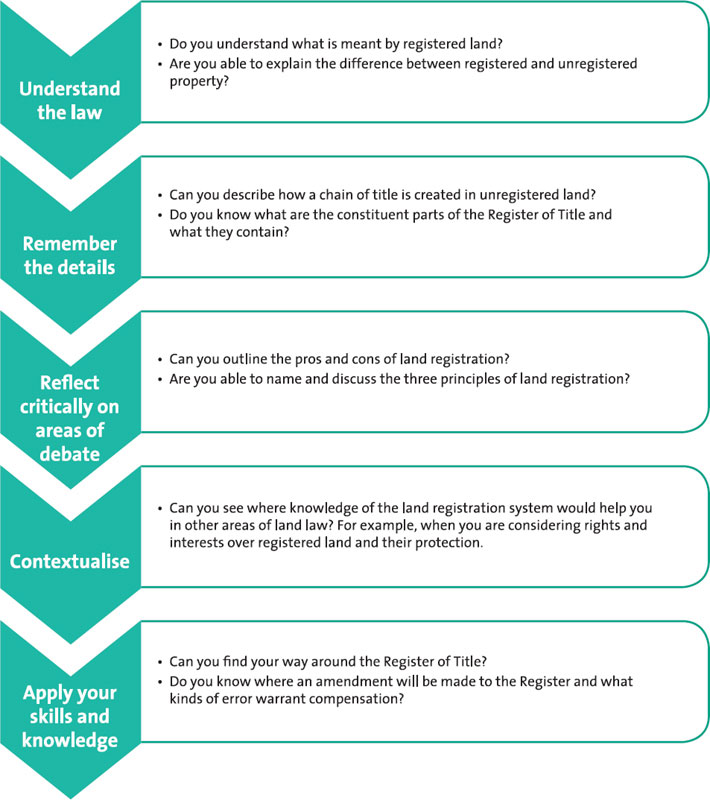

As you have already seen from Chapter 2, whether or not land is registered affects not only how the property is transferred and how that transfer is documented; it also dictates how interests affecting that land are protected and whether or not they can be overcome. Having a good understanding of registered and unregistered land is therefore vital to your understanding and application of land law. As you progress through the chapter, try to think about the differences between the two systems and how they might be applied on a practical level: for example, how the different classes of title might affect a sale of the property and how the same information might be discovered in an unregistered land scenario.

Why study both the unregistered and registered land systems?

At present, only around 75 per cent of the land in England and Wales is registered, the other 25 per cent remaining unregistered. As a result, anyone studying and practising land law must learn about both the unregistered and registered systems of landholding and transfer.

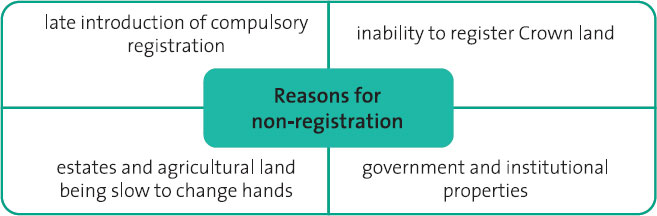

There are several reasons why, almost 90 years after the statute was imposed, large parts of England and Wales remain unregistered:

1. The registration of land across the country was slow to commence. Although the Land Registration Act came into force on 1 January 1926, registration remained voluntary in many areas until December 1990. Even then, it was only compulsory to register property on its sale; therefore gifts of land or land being handed down by will or in intestacy remained outside the requirement to register. In 1998, new ‘triggers’ for the compulsory registration of land were introduced, including gifts of land, transfers on death and mortgaging property. This has increased the rate of land registration considerably, but there is still some way to go.

For a full list of all the circumstances under which registration of title is now compulsory in England and Wales, take a look at Land Registry practice guide 1 on the Land Registry’s website, which is at: www.landreg.gov.uk/assets/library/documents/lrpg001.pdf

2. Under the original provisions of the Land Registration Act 1925, it was not possible to register land held by the Crown. This was because the statute made provision only for the registration of estates and interests in land, and not land owned absolutely, as is the case with Crown land. Section 79 of the Land Registration Act 2002 has resolved the problem, however, enabling the Crown to grant an estate in land to itself and which can in turn be registered.

3. Both farms and large country houses, which often have large swathes of agricultural land attached to them, tend to be passed down from generation to generation. They might therefore only change hands two or three times during the course of a century. Add to this the fact that it has only been compulsory to register a change of ownership on a death since 1998, and you are left with a situation where many of the country’s larger estates may continue to remain unregistered for another 30–40 years.

4. Government and other institutional properties also rarely change hands and in the case of large companies may never change hands at all. These properties are unlikely to be registered under the existing statutory provisions.

Unregistered land

Unregistered land is the name given to land that has not yet been registered under the 1925 land registration system, and to which the law that predates land registration must therefore be applied. As unregistered land does not appear on the centralised land register, the ownership of an unregistered property has to be proved by other means.

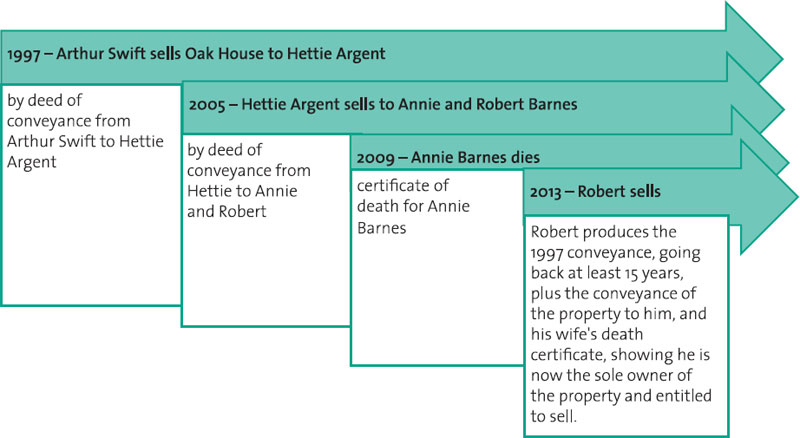

Whilst at first glance it might seem logical simply to provide the buyer with a copy of the deed that transferred the legal ownership of the property to the seller, this is not necessarily sufficient for conveyancing purposes. This is because unregistered conveyancing practice seeks to show the history of that property’s ownership over the course of a minimum of 15 years immediately preceding the sale, by tracing an unbroken ‘chain of ownership’ from owner to owner and ending with the seller.

In addition to proving a chain of ownership for the property, the seller also has to produce evidence of any interests that exist for the benefit of the property, or which restrict its use in some way. These may appear in other deeds or documents that predate the chain of title.

The following shows how a timeline in unregistered land converts into a chain of title for conveyancing purposes:

Problems with the unregistered conveyancing system

The unregistered system is not without its difficulties:

It is time consuming and expensive

It is time consuming and expensive

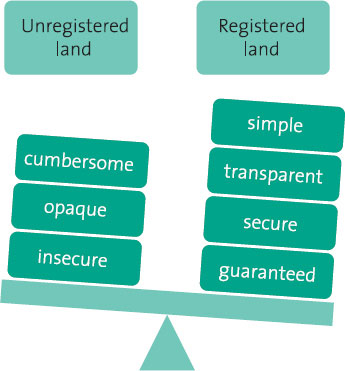

As can be seen from the illustration above, every time the property changes hands, the solicitor acting for the seller must carry out a check of the title deeds to produce evidence of an unbroken chain of ownership for the buyer’s solicitor. As the title deeds and documents can span many years or even centuries and does not come in a prescribed form, this can be a laborious and time-consuming process.

The system lacks security

The system lacks security

If the title deeds for the property are lost or stolen, proof of ownership is extremely difficult to establish, as its acquisition may not be documented elsewhere. In addition, the deed making the transfer legal no longer exists.

There is no transparency of ownership

There is no transparency of ownership

The private system of document holding prevents the State from building up any clear picture of who owns land at any one time and it can be difficult to find out who owns land in situations where it may be necessary to do so; for example, where the council wishes to make a compulsory purchase of property.

Understanding: land registration

Introduction

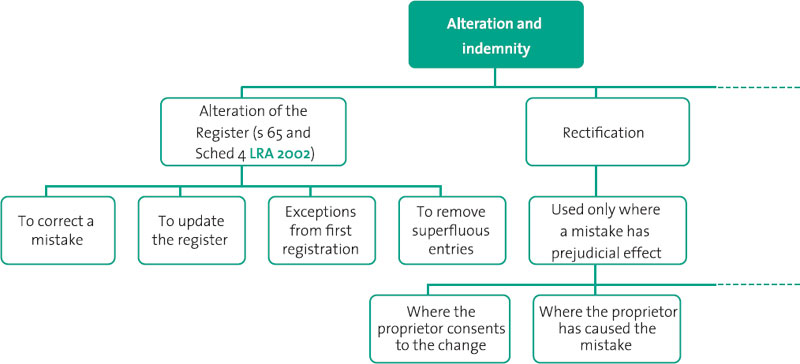

Land registration is governed by the Land Registration Act 2002, which superseded the Land Registration Act 1925. The 2002 Act has made very little additional change to the original provisions, however, its primary purpose being to pave the way for electronic conveyancing (whereby the transfer of land will take place electronically, as outlined in Chapter 2).

The purpose of land registration is to:

simplify the conveyancing process, the seller having to produce only one document: a copy of the register of title appertaining to the property being sold;

simplify the conveyancing process, the seller having to produce only one document: a copy of the register of title appertaining to the property being sold;

create a clear and public record of property ownership nationwide;

create a clear and public record of property ownership nationwide;

remove the difficulties caused by the loss or theft of title deeds, there being always a central record of the property to refer back to;

remove the difficulties caused by the loss or theft of title deeds, there being always a central record of the property to refer back to;

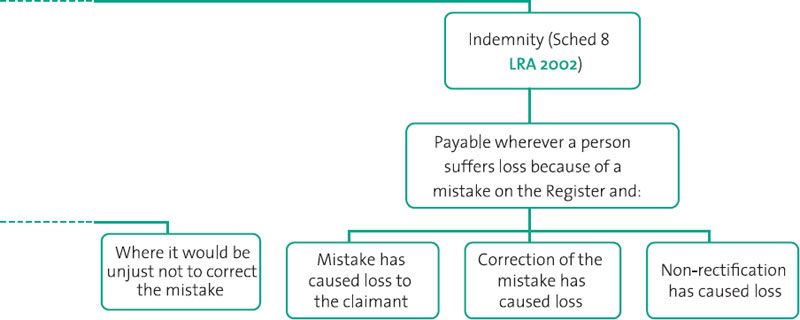

provide a guarantee from the State that the ownership of any given property is as it appears on the Land Register.

provide a guarantee from the State that the ownership of any given property is as it appears on the Land Register.

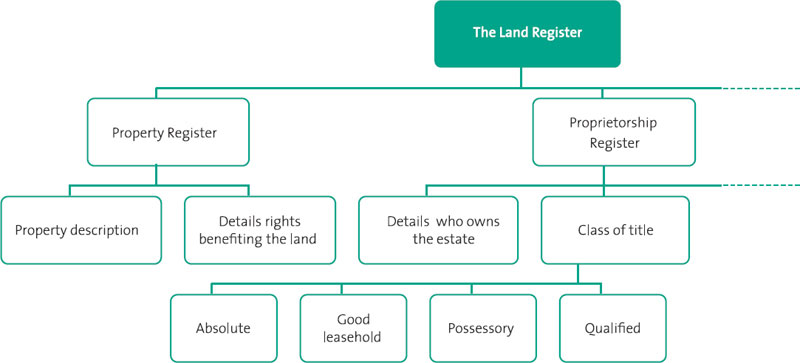

The Land Register

The Land Register is a vast database containing the details of around two million properties in England and Wales.

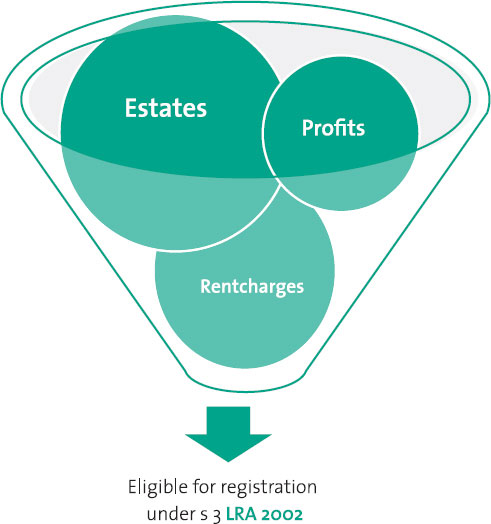

What can be registered?

The Land Registration Act 2002 provides, under s 3, in the main for estates in land to be registered under the land registration system, although some other interests that can exist ‘in gross’ (in other words you don’t have to have own an estate in land yourself in order to own the interest), such as rentcharges and profits à prendre, can also be afforded their own individual entry on the register. For the purposes of this chapter, we will be concentrating on the registration of estates in land.

All lesser interests are registered against the estates which they both burden and benefit, invariably in the form of a Restriction or Notice on the Register, as detailed in the previous chapter.

Each estate in land is recorded individually on the register under its own unique title number. This makes the task of proving title to the property on a sale quite a simple one: the seller’s solicitor simply looks at the Register of Title for that particular property and gets all the information he or she needs for the sale. As was mentioned earlier in the chapter, the entries on the register come with a State guarantee, so the buyer’s solicitor can be confident that they can rely on the information contained within it.

The details for each property are recorded on the register in the following way:

This is a copy of the register of the title number set out immediately below, showing the entries in the register on 2 April 2013.

TITLE NUMBER: DV748953

PROPERTY REGISTER

DEVON: FRODSHAM

1. (12 June 1990) The Freehold land shown edged with red on the plan of the above Title filed at the Registry and being 32 Hill Close, Frodsham (DV6 6LR).

‘TOGETHER WITH the benefit of a right of way through the passage that passes across the rear of 34 Hill Close.’

END OF PROPERTY REGISTER

TITLE NUMBER: DV748953

PROPRIETORSHIP REGISTER

ABSOLUTE FREEHOLD

1. (20 August 2009): PROPRIETOR: ELLIE-MARIE STRUTHERS and JORDAN LUKE STRUTHERS of 32 Hill Close, Frodsham (DV6 6LR).

2. (20 August 2009) Except under an order of the registrar no disposition by the proprietor of the land is to be registered without the consent of the proprietor of the charge dated 20 August 2009 in favour of the Devon Bank plc referred to in the Charges Register.

END OF PROPRIETORSHIP REGISTER

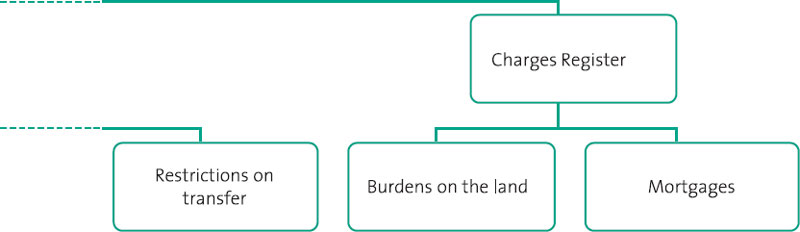

TITLE NUMBER: DV748953

CHARGES REGISTER

1. (12 June 1990) A Conveyance of the land tinted pink on the title plan dated 16 October 1978 made between (1) Shane Lott (Vendor) and (2) Arlo James Bridgcombe (Purchaser) contains the following covenants:-

‘THE Purchaser hereby covenants with the Vendor that the Purchaser and his successors in title will not use the whole or any part of 32 Hill Close for business purposes.’

2. REGISTERED CHARGE dated 20 August 2009 to secure the moneys including the further advances therein mentioned.