Regional Seas Programme: The Role Played by UNEP in its Development and Governance (Elizabeth Maruma Mrema)

REGIONAL SEAS PROGRAMME THE ROLE PLAYED BY UNEP IN ITS DEVELOPMENT AND GOVERNANCE

Elizabeth Maruma Mrema

10.1 Introduction

Over the years, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has played a pivotal role and led the development of several international conventions1 and regional agreements2 in various areas in the environmental arena, including regional seas instruments, which are the basis of this chapter. UNEP currently administers eight global3 and nine regional conventions4 as well as one global programme of action.5

Consequently, this chapter reviews and assesses the role UNEP has and continues to play in the development, administration, and management of a specific branch of international environmental law, namely, regional seas conventions and action plans forming part of the UNEP Regional Seas Programme and particularly, those for which UNEP provides Secretariat and coordination functions.

The chapter begins with the role UNEP has generally played in the development of the regional seas conventions through a series of its ten-year environmental law programme, in which protection of the marine environment has been a priority activity since it began in the 1980s. Development of regional seas programmes through the regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols has been a priority programme of UNEP since it was established in 1974, as demonstrated through various UNEP Governing Council (UNEP GC) decisions taken over the years. An overview of the provisions of the regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols in general and the role UNEP plays in their management is provided, including the influence UNEP had in ensuring that all regional seas programmes followed the same or similar pattern. Institutional arrangements for the regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols as well as funding mechanisms and the role UNEP has played in them are discussed. The chapter concludes with the challenges being faced by some of the regional seas conventions and action plans (RSCAPs) arrangements.

10.2 Context of the Regional Seas Programme

10.2.1Development and setup of regional seas programme

The Regional Seas Programme was launched in 1974 after the establishment of UNEP and has continued to grow to become one of UNEP’s significant achievements and a global flagship programme implemented through regional frameworks for cooperative management and protection of shared marine and coastal environment. The UNEP GC has since then repeatedly6 endorsed a regional approach for the control of marine pollution and the management of marine and coastal resources. It has also requested UNEP to take the lead in the initiation, development, and support implementation of the regional seas action plans as well as the ensuing regional seas conventions and protocols. The Programme was set up to address accelerating environmental degradation of the world’s shared marine and coastal areas, including management of the natural resources through concerted and comprehensive actions among neighbouring countries sharing a specific body of a sea or ocean. As such, the Programme continues to be shaped according to the needs of a specific region with the overall strategy being defined by the UNEP GC. Such strategy has included the promotion of international and regional conventions, guidelines and actions for the control of marine pollution, and protection and management of aquatic resources. Furthermore, the Programme promotes regional and international cooperation for the marine and coastal environment in the context of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)7 to protect the shared marine environment.

For instance, in June 1973, UNEP GC designated oceans as one of the UNEP’s priority programmes and the programme has undergone significant expansion since then. In this regard, the Governing Council adopted the following actionable areas for UNEP to implement:

This decision was the basis for the development of non-legally and legally binding instruments under the UNEP Regional Seas Programme which has remained valid to date. The Regional Seas Programme was thus initiated as a UNEP action-oriented coordination programme over its administered and non-administered regional seas programmes through the development of action plans for the sound management of the marine environment and conventions, as well as their associated protocols covering different regions of the world. However each programme is managed differently depending on the uniqueness and circumstances of each region.

To date, eighteen regional seas programmes8 participate in this coordination programme governed through annual Global Meetings of the Regional Seas Conventions and Action Plans organized by UNEP. Global strategies for cooperation and the role of the regional seas programmes have been adopted through these meetings.9 These meetings channel UNEP programmatic support to the regional seas conventions and action plans, particularly in areas complementary to the UNEP programme of work. They also strengthen linkages between the regional seas conventions and action plans and other relevant global conventions and agreements.

Currently, over 143 countries participate in the thirteen Regional Seas Programmes established under UNEP auspices.10 Of these, UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions to six programmes. Four of these programmes consist of legally binding regional seas conventions,11 while two consist of regional seas action plans without legally binding conventions.12 UNEP also provides secretariat and coordination functions to the global programme of action for the protection of the marine environment from land-based activities (GPA).

In the regions, the regional seas programmes are implemented through established secretariats called ‘Regional Coordinating Units’ (RCUs).13 Regional Activity Centres (RACs)14 have been established and funded by governments as national institutions, but carrying out regional activities in support of the implementation of conventions, protocols, and/or action plans in close collaboration with RCUs with varying degrees of success and challenges. In some cases, ‘Regional Activity Networks’ (RANs)15 have also been established to provide expertise needed for the execution of activities undertaken by RACs.

Of the twelve programmes for which UNEP does not provide secretariat or coordination functions, some16 have been developed under the auspices of UNEP17 and UNEP served as an interim secretariat in a number of them in their initial years, until their own secretariats were established.18 For these programmes, other identified regional organizations would normally host and provide secretariat functions as well as manage their own financial resources (trust funds). Nonetheless, they continue to cooperate in the implementation of their regional activities as part of the cooperation and coordination arrangements under the global regional seas programme spearheaded by UNEP.19

Moreover, there are five independent partner programmes in five regions20 which also form part of the global regional seas programmes. These programmes participate in the UNEP organized Annual Global Regional Seas Coordination Meetings as well as different activities and projects for the protection and restoration of the marine and coastal environment in their respective regions.

10.2.2. UNEP administered regional species agreements vs. regional seas conventions

In addition to the above regional seas conventions, whose scope are based on geo-political boundaries for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions, there are more legally binding and non-legally binding regional seas instruments also negotiated under UNEP’s auspices. In some cases, UNEP provide secretariat functions, but their focus is on the conservation of specific migratory marine species within a particular region. Such agreements include: (i) 1992 Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North-East, Irish, and North Seas (ASCOBANS) administered and hosted by UNEP,21 (ii) 1996 Agreement on the Conservation of the Cetaceans of the Black Seas, Mediterranean Sea, and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS) administered and hosted by the Government of Monaco,22 (iii) 1988 Trilateral (Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands) Agreement on the Conservation of Seals in the Wadden Sea Seals administered and hosted by the Government of Germany,23 (iv) 2001 Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP-Birds).24 These legally binding agreements were negotiated and adopted under the auspices of UNEP through Article IV of the global framework Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (UNEP/CMS).

In addition, seven more non-legally binding regional seas migratory species memoranda of understanding (MOUs) have also been negotiated and adopted under the UNEP/CMS auspices.25 Their secretariat functions are equally provided by UNEP through the UNEP/CMS secretariat and are located in Bonn, Germany except one, namely, MOU on the Conservation and Management of Dugong and their Habitats, whose secretariat is located in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Within UNEP these instruments unfortunately are coordinated through two different Divisions. Regional Seas Conventions and Action Plans are coordinated through the Freshwater and Marine Ecosystem Branch of the Division of Environmental Policy Implementation (DEPI), while the regional migratory marine species agreements and MOUs are managed within the Division of Environmental Law and Conventions (DELC), which is the focal point for the global multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) including their framework instrument, CMS. Unfortunately, these instruments as well as their secretariats are not included as part of the UNEP Global Regional Seas Meetings except for occasional invitations to attend such meetings as observers, and not necessarily in the cooperative arrangement for their implementation of specific aspects of these agreements and MOUs. They are also sometimes invited to the meetings (Conference of the Parties—CoPs or Intergovernmental Meetings—IGMs) of the individual Regional Seas Programmes with limited programmatic interactions. Further review and analysis of the coordination and management mechanisms used by UNEP to effectively build cooperative arrangements among these relevant secretariats it administers are beyond the scope of this chapter.

10.2.3Impact of UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on the RSCAPs

UNCLOS, also referred to as the ‘Constitution’ of the oceans, adopted in 1982,26 sets out a comprehensive legal framework for conservation and sustainable use of all oceans and their resources and provides the basis for national, regional, and global action and cooperation in the marine sector.27 With regards to the protection and preservation of the marine environment, Part XII of UNCLOS provides a framework upon which the regional seas conventions and protocols are negotiated and developed in response to its call for cooperation on a global and regional level in the formulation and elaboration of international rules, standards or recommended practices for the protection and preservation of the marine environment.28 UNEP, through its Regional Seas Programme as well as its Governing Council has had its influence in the development of Part XII of UNCLOS on the marine environment. The third session of the Governing Council in 1975 urged the negotiations at the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea ‘to attach the highest priority to incorporate in the draft treaties effective provisions for the protection of the marine environment’.29 There are forty provisions currently reflected in Part XII of UNCLOS in Articles 197 to 237, most of which have been incorporated in the framework regional seas conventions and further elaborated through specific protocols30 developed under the conventions. In addition, Parts XIII and XIV related to marine research and development and transfer of technology have equally played a significant role in the development of the regional seas programme. Considering that UNCLOS largely codified customary law and practice in the field of the protection and preservation of the oceans, it is not surprising to see provisions of Part XII amongst others already reflected and incorporated into the regional seas conventions and protocols adopted before UNCLOS was codified and after it was adopted.

Clearly, the pivotal role played by international organizations such as UNEP in the initiation and development of regional seas conventions and protocols were not only recognized by the UNCLOS but it has specifically called upon UNEP to respond. This role is demonstrated by the increasing number of regional seas conventions and protocols that were initiated, negotiated, and adopted in the past four decades. The development and adoption of fifteen regional seas conventions (six of which UNEP provides with secretariat and coordination functions), sixteen action plans (the majority with conventions but a few with no conventions yet: UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions for two of them), and forty-two regional seas protocols31 clearly shows the influence and impact that UNCLOS has had and continues to have on the development of these instruments. This influence has been further coupled with UNEP’s strengthened role through the repeated mandates it continues to be accorded by its governing body as well as its influence in the negotiation and development of UNCLOS.

10.3 Overview of the Regional Seas Action Plans, Conventions, and Protocols

10.3.1Regional seas action plans

The Regional Seas Programme, composed of regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols, has evolved over the years and has had a common methodology in its development. At the request of governments UNEP, through specific decisions of its Governing Council,32 and using its leadership, technical expertise, catalytic role, and convening power, as well as seed funding, has initiated and supported consultative intergovernmental negotiations processes for the development of regional seas action plans. Most of these action plans have called for and led to the development and adoption of the umbrella legally binding framework conventions and implementing protocols except for a few, such as the NOWPAP and COBSEA, both of which UNEP provides with secretariat and coordination functions, and SASAP, administered by SACEP, which have still remained at action plan status. For the two Action Plans for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions, their implementation status through the established RCUs and RACs does not differ from the four legally binding conventions for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions also through their RCUs. The same is probably true of the implementation status for SASAP through SACEP.

UNEP, in cooperation with other UN bodies and international organizations, provides States with a forum, in which they meet, negotiate, and cooperate in order to protect common and shared regional marine resources. In most cases, UNEP, in collaboration and/or consultation with relevant international and regional organizations, undertakes inter-agency fact-finding missions to the countries of the region, and based on these findings, organizes a meeting of national focal points in the specific region to brainstorm and identify priority areas of regional concerns or challenges. Recommendations for preparation of country and/or regional assessment reports are thereafter developed. Such meetings would ordinarily be followed by a convening of legal and/or technical experts to review the country reports and draft regional reports, leading to the development and drafting of an action plan for the protection of the marine and coastal environment of the region.

The action plan specifies regional needs and areas requiring effective and sound management of the marine environment, taking into account international developments in the subject areas where priority activities will need to be developed for the implementation of the action plan. The action plan for protection and development of the marine environment and coastal areas is thereafter agreed and adopted at a meeting of plenipotentiaries of the Member States and in some cases, opened for signature and thereafter ratification or accession. UNEP has thus succeeded in ensuring that a consistent integrated approach has been followed in the development of most, if not all, existing regional seas action plans and safeguarded the maintenance of an inter-disciplinary character of environmental problems. Through its Regional Seas Programme and in collaboration with other relevant international and regional organizations, UNEP acted as the overall coordinator and facilitator for the development and implementation of the regional seas action plans.33

Such a process for the development of a regional seas environment programme normally entailed the development of, first, a regional action plan outlining the strategy and substance of a coordinated programme formulated in response to the environmental needs, priorities, and challenges of a given region. So far, all existing action plans are structured in a similar format and content as provided for in the ‘Guidelines and Principles for the Preparation and Implementation of Comprehensive Action Plans for the Protection and Development of Marine and Coastal Areas of the Regional Seas’.34 The format and content normally include first and foremost chapters or components related to environmental assessments, environmental management, environmental legislation, institutional arrangements, and financial arrangements. The action plans are then underpinned by a strong legal framework in the form of a regional cooperation treaty or convention and associated implementing protocols dealing with specific marine related problem(s) and issues. The legally binding convention expresses in clear terms the commitment and political will of governments to tackle their common environmental issues through jointly coordinated activities. However, as stated earlier, not all regional seas action plans have been translated into legally binding framework conventions and protocols, as they are still at the action plan status (such as NOWPAP and COBSEA). These action plans, however, implement their activities and projects through the coordination of the formal established regional seas coordinating units and regional activity centres hosted by national institutions/governments just like the framework regional seas conventions and protocols (See Appendix 2).

An action plan is legally speaking considered to be a non-legally binding or soft-law instrument, similar to guidelines, codes of conduct, and arguably also resolutions or decisions emanating from major international conferences or governing bodies. Some of the regional seas action plans35 are not only negotiated and adopted but also opened for signature followed by ratification or accession, and determining an effective date for their entry into force, in the same manner as an internationally binding treaty. Consequently, despite the terminology used, regional seas action plans which have gone through this process should in essence be considered under international treaty law as legally binding. However, some regional seas action plans36 have only been adopted and became effective soon after and thus can be considered to be soft-law instruments.

In addition to the neutrality, convening power, and catalytic role that UNEP has played, it also provides support measures to Governments, especially those of developing countries, to enable them to participate effectively in the development and management of the regional seas action plans as well as the ensuing conventions and protocols. Such support has included provisions of technical assistance and capacity building in the form of direct or in-kind financial support37 for targeted activities, training, provision of equipment, technical expertise to support and improve the ability of national institutions, and/or establishment of specialized regional activity centres, and so forth.

Together with the generic framework for the regional seas action plans, UNEP equally spearheaded the development and adoption of a global programme of action intended to tackle a specific environmental problem, namely, the 1995 GPA, which it also hosts and provides with its secretariat services. Although a non-legally binding instrument in nature, its implementation does not differ from any legally binding treaty for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions. Nonetheless, GPA provides a legal framework mechanism for both the development and implementation of the regional seas conventions and protocols, and its implementation through the regional seas programme.

10.3.2. Regional Seas Conventions

The regional seas action plans call for the development and adoption of legally binding regional framework conventions, supplemented by protocols elaborating specific marine pollution issues for the parties to be obliged to take specific actions in collaboration and cooperation among themselves for the protection of marine resources and prevention of coastal and marine pollution. Consequently, the existing regional seas conventions and protocols do in fact respond to the implementation of the provisions of adopted action plans. However, for the regional seas action plans not translated into framework conventions and protocols, parties to the action plans still agreed to take specific actions and implement them as stipulated in the plans for the protection of the marine resources and prevention of coastal and marine pollution.38 Just like the regional seas action plans, as indicated earlier on, most existing regional seas conventions, be they provided with secretariat and coordination functions by UNEP or not, have been spearheaded by UNEP, in collaboration with other international organizations, in response to decisions taken by UNEP Governing Council decisions. These decisions had requested UNEP to facilitate and support the intergovernmental negotiation processes for the development of different regional seas conventions. Accordingly, similar methodology as for the action plans has been used, in particular, facilitating and supporting the drafting of the framework convention and subjecting the draft to review by national and regional legal experts before being finally reviewed for adoption by an intergovernmental regional meeting of senior officials.

Regional seas conventions do provide a platform for regional cooperation, coordination, and collaborative actions that permit the participating countries, despite their political differences, to harness resources and their expertise to solve common marine and coastal environmental problems. The regional legal framework provided by the conventions and protocols enables participating countries to jointly agree on their priorities and plan and develop programmes for the sustainable management, protection, and development of their marine and coastal environment. The framework also offers a unique forum for intergovernmental debates on their regional environmental challenges, and strategies to address them. In view of the pattern that evolved in the development on the drafting of the regional seas action plans and the role UNEP played and the influence it had in that process, it is not surprising that most if not all of the existing regional seas conventions do also follow a similar pattern in their development process, contents, and issues covered by each of them.

10.3.2.1 Contents of the regional seas conventions

The flow of the provisions/articles of the regional seas conventions’ chapters and contents are, like the regional seas actions plans, principally similar. For instance: all have more or less similar titles save for regional specificities, with some differences to the latter conventions which have included sustainable development and management in the titles signifying developments in international law. For instance: the title ‘Convention for Cooperation in the Protection of the Marine and Coastal Environment’ seems to be popularly used by all of the instruments. However, some of the earlier conventions have specified the nature and expected result of the instrument, such as protection of the environment ‘from pollution’ (Kuwait Convention) or ‘against pollution’ (Black Sea Convention and the old Barcelona Convention) or ‘conservation’ (Apia Convention, Jeddah Convention) or ‘protection and development’ (Cartagena Convention, Abidjan Convention) or ‘protection, management and development’ (Nairobi Convention) or ‘protection and sustainable development’ (Antigua Convention, revised Barcelona Convention). See Appendix 1.

Successively therefore, all such conventions have similar or related types of provisions. For instance, inter alia, geographical scope/coverage, general provisions, general obligations followed by specific obligations related to specific types of pollution, such as from ships, land-based sources and activities, transboundary movement of hazardous wastes, airborne, caused by dumping, to mention but some of the identified sources of key pollution issues covered for implementation by the conventions. Other common provisions include cooperation among parties in: combating pollution and environmental damages, scientific and technical matters, the development and adoption of additional protocols, annexes and amendments thereof, liability and compensation,39 and development of financial rules, to mention but a few.

To ensure effective implementation of the conventions and the review of such implementation, provisions are included in all conventions related to institutional arrangements including different governing bodies for the conventions as well as financial arrangements to support the implementation of the conventions and their programme of work and activities. Conventions adopted after the 1992 Rio Conference on UNCED included many of the aspirations of its Agenda 21, and existing conventions expanded their provisions to reflect those aspirations, as well as other developments in international environmental law. Consequently, provisions related to contribution to sustainable development, the precautionary principle, the ‘polluter pays’ principle, access to information and data to stakeholders to enable them to participate in the decision making processes affecting them, and environmental impact assessment, to mention but a few, have been added in later or amended conventions as part of the general obligations of the parties.40 Likewise, to ensure effective review of the progress made by the parties through the national reports, among others, submitted to the conferences of the parties, provisions related to the establishment of compliance and enforcement regimes are more and more added into the latter or amended conventions or adopted through specific decisions by the parties.41

10.3.2.1.1 Geographical scope Different options, for instance, have been used to determine geographical coverage or scope for each specific regional convention mostly based on geographical-political grounds. Some regional conventions have utilized sea area latitudes and longitudes (Kuwait Convention) while others used specific jurisdictional areas demarcated by country or regional areas or limits (Abidjan Convention, Black Sea Convention, and the Barcelona Convention) to determine geographical limits for the convention coverage. Some have excluded internal waters of the Parties from the scope of the convention (Cartagena Convention and Kuwait Convention) and another has used the UNCLOS maritime areas as the basis for its scope of application (Antigua Convention). Others permit the parties to further extend the coverage as may be defined by each party within their territories (Barcelona Convention) or define the areas on the basis of the entire watershed such as riparian, marine, and coastal environment including watershed (Nairobi Convention).

There have, however, been discussions at the recent Global Regional Seas Meetings, with no conclusive decision made yet, on whether or not parties to the various conventions should not consider reviewing and revising the way geographical coverage of the different conventions had been determined and considered, in view of and in response to the integrated ecosystem approach being introduced to a number of regional seas programmes. Regional seas action plans have been developed, aligned, and implemented in accordance with the UNEP mandate and priorities, since the regional seas programme is part and parcel of the UNEP approved programme. Recent UNEP priorities have been determined and prioritized in accordance with emerging international developments and in recent years focused on ecosystem management and approach, as well as the green economy, which has in turn also influenced priorities determined by the regional seas programmes. Most of the existing regional seas action plans focus on assessment, monitoring, and normative actions without addressing the sources of pollution and threats to the functioning of the ecosystem; thus the need to address this, making them more effective in improving the quality of the ecosystems as intended.

Furthermore, even the regular reviews of the state of marine environment reporting are carried out based on assessments, and not always on identifying the drivers for ecosystem changes and threats to ecosystem functioning, thus failing to target specific actions required to address the cause of degradation of quality and functions of ecosystems. The current geographical coverage of the regional seas action plans and conventions has been decided through political considerations and based on geo-political boundaries, instead of taking into account ecological functions and continuity. This makes it difficult to respond to the current activities and realities through an ecosystem approach, based on assessments of ecosystems processes and functions, optimal ecosystems, and goods and services for human benefit. As a result, the need to address the sources of stress and threats associated with human activities on the ecosystems could be more effectively answered.42

Responding to these threats may require extensive updating and revising of the action plans so as to focus on current trends towards the ecosystems approach, to produce specific benefits for human beings, and thus to reconsider the current geographical coverage in the conventions from the traditional geo-political boundaries to ecological boundaries. The emerging focus on ecosystem approach has been highlighted and enshrined in the latest Regional Seas Programme’s Strategic Directions, 2013–2016 which aim at strengthening the implementation of the regional seas conventions and action plans at a global level. They ‘endeavor to effectively apply an ecosystem approach in the management of the marine and coastal environment in order to protect and restore the health, productivity, resilience of oceans and marine ecosystem …’43 the implementation of which may necessitate a review of the existing action plans as well as nature of the conventions’ geographical scope.

10.3.2.1.2 General provisions Similar assumptions have been considered or taken by different regional seas conventions under general provisions guiding the entire framework instruments save for the Black Sea Convention, which has similar provisions but in three different articles (on general provisions, sovereign immunity, and general undertakings), all of which can be considered together with other instruments as general provisions. Parties to them have agreed that their conventions as well as ensuing protocols will be implemented and construed in accordance and in conformity with international law.44 They have agreed to respect each party’s rights and duties, respect their national sovereignty and independence and non-interference into each other’s internal affairs.45 Furthermore, parties have protected their prior obligations assumed under previously concluded agreements as not to be affected by framework convention or protocols46 including or in particular, UNCLOS.47 Each other’s respect for possible present or future claims and legal views concerning the nature and extent of maritime jurisdiction has also been secured.48

Likewise, they have safeguarded their sovereign immunity of warships or other ships owned or operated by their States under international law as not to be affected by the conventions or resulting protocols.49 Despite all the above exemptions agreed for the regional seas framework conventions and protocols, parties to them have nonetheless agreed to conclude other bilateral or multilateral or regional or sub-regional agreements for the protection and management of the marine and coastal environment of their specific convention areas, as long as such arrangements do not conflict and are consistent with the framework conventions and ensuing protocols.50

10.3.2.1.3 General Obligations All regional seas conventions provide different types of legal obligations requiring the parties to them to undertake measures either individually, jointly, regionally, or cooperatively in accordance with each convention and within applicable rules of international law to prevent, abate, and combat pollution of the specified marine or coastal areas. Different types of obligations have been agreed by the parties and can be observed in both framework regional seas conventions as well as the resulting protocols. For instance, the use of either general mandatory and outcome focus binding requirements indicating the provisions which must be implemented by the parties (determined by action words such as ‘shall’, ‘must’, and ‘will’) or use of discretionary and effort focus non-binding requirements with provisions showing a certain degree of flexibility on their implementation by the parties, indicated by the action word ‘may’. Provisions also differ in terms of providing general or specific actions to be undertaken or outcomes to be achieved by the parties. Other obligations require the parties to cooperate on measures or efforts at regional or national level and/or jointly to take specific actions on specific issues.51

Accordingly, each and all contracting parties under all regional seas conventions are obliged under the general obligations provisions to undertake the different appropriate measures pursuant to their conventions and for their effective implementation.52 These include obligations not to cause pollution of the marine environment beyond their geographical area, to cooperate in the development and adoption of protocols or other agreements, to adopt national legislative and administrative measures for the effective discharge of the obligations prescribed, and endeavour to harmonize their policies as well as to cooperate with other international bodies to undertake measures which contribute to the protection and preservation of the marine environment and ensure effective implementation of the convention in conformity with international law. Regional seas conventions adopted after 1992 UNCED (eg the 2010 Amended Nairobi Convention, 1995 Barcelona Convention, 2002 Antigua Convention and the revised draft Abidjan Convention) include Agenda 21 principles as part of the general obligations. Thus parties are obliged to apply the following environmental principles in their protection and preservation of the marine environment, namely: the precautionary principle, polluter pays principle, contribution to sustainable development, environmental impact assessment, public participation in decision making, availability and exchange of information and data, and promotion of integrated coastal zone management in the protection of the marine environment.

10.3.2.1.4 Specific obligations Recalling that problems related to marine pollution were the major impetus for the development of the regional seas programme, all existing regional seas conventions contain specific obligations for the parties to take all appropriate measures in conformity with international law to prevent, abate, combat/control, and to the extent possible remedy/eliminate pollution from the different sources or causes.53 Such sources of marine pollution include: dumping from ships or aircraft; incineration at sea;54 discharges from ships or vessels;55 exploration and exploitation of the continent shelf and seabed and its subsoil;56 land-based sources;57 transboundary movements and disposal of hazardous wastes; and atmospheric pollution.58 Other obligations include:, protecting biological diversity,59 rare or fragile ecosystems, threatened and endangered species of flora and fauna and their habitats;60 establishing protected areas;61 and, finally, but not least, controlling coastal erosion as a result of human activities, as well as measures aimed at an integrated management and sustainable development of the marine and coastal environment. Most of these specific obligations have led in time to the development and adoption of detailed specific regional seas protocols. See Appendix 1.

10.3.2.2 Regional Seas Protocols

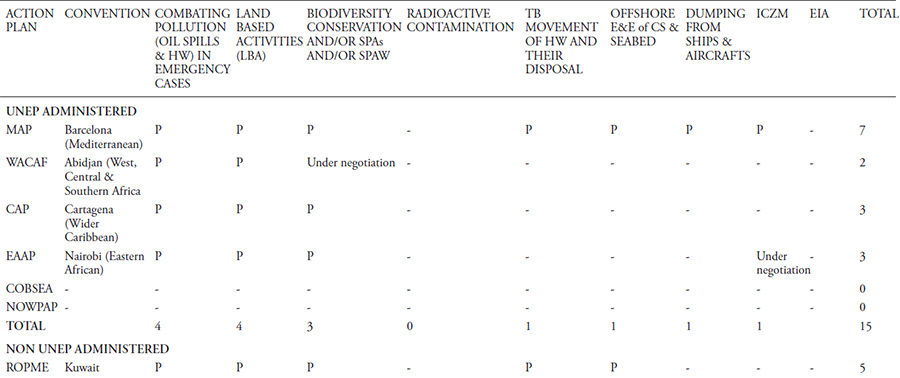

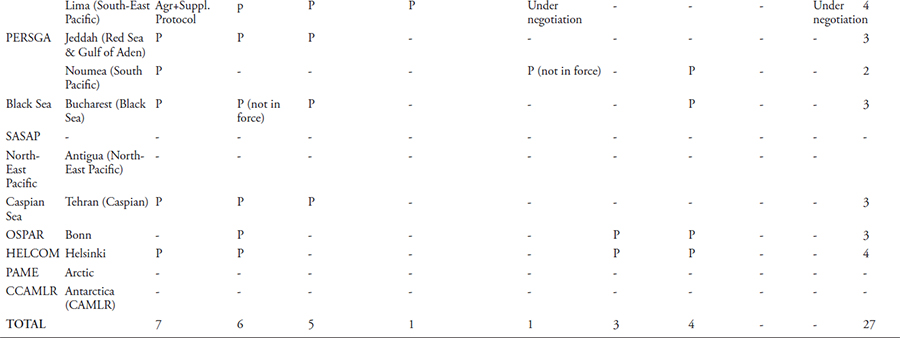

The specific obligations62 of the parties provided for in the regional seas conventions are framework in nature, leaving the details to be further elaborated through separate and independent legally-binding protocols. Consequently, as envisaged by each of the regional seas conventions, under the general obligation that parties will cooperate to develop protocols, a total of about forty-two legally binding protocols on different and specific issues on marine pollution have been developed over the years (fifteen under UNEP-administered regional seas conventions and twenty-seven under other non-UNEP-administered conventions. Four are under negotiation and two adopted but not yet in force).63 Protocols on the following issues have been adopted to date, namely: prevention of pollution by dumping including from ships and aircraft (four64), procedures in cases of emergency (eleven65), pollution from land-based sources and activities (seven66) and from exploration and exploitation of the continental shelf and seabed and its subsoil (two67).

Others include protocols on: transboundary movements of hazardous wastes and their disposal (three and one being negotiated68), combating oil spills (one plus three contingency plans under action plans69), radioactive contamination (one70), and on the El Niño (one71), integrated coastal zone management (one and two being negotiated72), the conservation of biological diversity or wildlife and specially protected areas (seven plus one under negotiation73) and one on environmental impact assessment under negotiation.74 See also Appendix 1. Of these protocols, UNEP’s role and influence was more visible in the development of the protocols related to the prevention of marine pollution from land-based sources and activities, as most of them have been developed after the adoption of GPA in 1995 and as part of its implementation through the regional seas conventions and action plans.

10.4 Institutional Arrangements

10.4.1Intergovernmental meetings (IGMs)/Conferences of the Parties (CoPs)

Effective implementation of the regional seas action plans, framework regional seas conventions, and ensuing regional seas protocols depend as a condition sine quo non on active participation and cooperation as well as well-coordinated, efficient, and effective institutional structures or arrangements put in place at regional and national levels by the parties. In this regard, at regional level, all regional seas action plans and conventions have established either intergovernmental meetings (IGMs) for the action plans, or conferences of the parties (CoPs) for the conventions/protocols, both with similar functions and responsibilities, namely, the overall authority to provide policy guidance and act as a decision-making organ for the implementation of the instruments. IGMs75and/or CoPs76 which, inter alia, keep under review the progress achieved in the implementation of the action plans and conventions, review and approve the programme of work and its budget as well as adopt, review and amend annexes to the conventions and their related protocols including proposals for additional protocols or amendment to the convention or protocols, to mention but few.

To fulfil the above tasks, parties meet at regular intervals as stipulated in the action plans and conventions, normally annually or every two years for the IGMs and every two years for most of the CoPs, except for the Black Sea Convention and Kuwait Convention which meet annually, and at a request by a party, ad hoc extraordinary meetings can be convened to discuss specific urgent agenda item(s). In between CoPs and IGMs, the leadership of the CoPs or IGMs, known as the Bureau, either as stipulated in the text of the convention itself (Barcelona Convention, Art. 19) or in the rules of procedures. The Bureau, composed of representatives of the parties or Member States and elected based on the principle of geographical representation, serves as an intersessional decision-making body for the parties and thus provides overall coordination, direction, and oversight of the work of the secretariat in the name of the RCU. Additionally, other roles for the Bureau include providing guidance and monitoring implementation of decisions of the CoPs or IGMs, as well as preparing documentation for the next CoP or IGM, as the Bureau would meet officially in between CoPs or IGMs.

10.4.2National institutions

Implementation and enforcement of priority activities identified in the various regional seas action plans as well as decisions of the IGMs and CoPs are principally undertaken by the Member States and parties at national level, and through cooperation between them at regional level. To monitor and follow up implementation of activities at national level and serve as a communication channel between the parties or Member States and for the convention or action plan, each Member State or party has an obligation to designate an appropriate government authority known as the National Focal Point (NFP) for purpose of communications with RCUs as well as monitoring national implementation of the action plan or convention. This obligation is either stipulated in the action plans77 or conventions78 or agreed by the parties through specific decisions of the IGM or CoP. Other roles and responsibilities of the NFPs include coordination, and participation of national institutions and government in the development and implementation of approved projects. At the national level, other national institutions or personnel referred to as National Project Coordinators (NPCs)79 can be designated for specific purposes of coordinating execution of funded projects, and to manage and monitor the implementation of specific projects. NPCs can include academia and research centres, as executing or implementing agencies for specific projects or programmes. To ensure a high degree of efficiency and accountability, all these national institutions form National Coordinating Committees80 to manage and monitor implementation of regional programmes and activities.

10.4.3Regional Coordinating Units (RCUs)

At regional level, all action plans and conventions have established a secretariat known as a Regional Coordinating Unit (RCU) to ensure effective technical management, coordination, and continuous monitoring of implementation of activities, programmes, and projects under the action plans or conventions and protocols. At the request of the parties, UNEP has been designated to provide secretariat services under two regional seas action plans,81 one global programme of action, the GPA,82 four regional seas conventions, and by extension their protocols.83 Other regional seas conventions, although negotiated under UNEP auspices as mandated by its GC decisions, as decided by the parties, are administered independently through established independent organizations. Nonetheless, even for those independent regional organizations,84 UNEP had played a significant role in their negotiation processes. This necessitated the parties to still request UNEP to serve as a secretariat or interim secretariat in the earlier years of the existence of such secretariats, either through the provisions of the conventions themselves85 or specific decisions of the CoPs,86 until dedicated organizations or bodies were established for the purpose.

As discussed earlier, regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols are fully integrated into UNEP’s regional seas programme under its programme of work as approved by its GC. This clearly shows that they are not independent entities, as are the global environmental conventions which UNEP also provides with secretariat and coordination functions.87 It is not surprising, therefore, that the regional seas action plans and conventions secretariats are called RCUs88 headed by Coordinators and not secretariats, as is also the case with UNEP-administered global conventions, headed by Executive Secretaries. Consequently, the six RCUs are all administered by UNEP and provide secretariat and coordination functions through the Regional Seas Programme within the Division of Environmental Policy Implementation (DEPI), a division currently responsible for the coordination and monitoring of the implementation of the regional seas programme, including the regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols.

UNEP, as an administrator of the RCUs, is responsible for the recruitment of the RCU staff who are UN staff members obligated to abide by UN rules and regulations. In addition, UNEP is also responsible for, but not limited to, procurement, financial management and audits, investigations, if any, to mention but a few. The staff of the RCUs are not only accountable to the Executive Director of UNEP through the Director of the Division responsible for the Regional Seas Programme (currently DEPI) for all administrative services, functions, and financial management, but also to their parties for the substantive functions of the RCUs as related to the implementation of the approved programme of work of the RCU. These include its approved budget and expenditures including implementation of decisions adopted by different IGMs or CoPs and their other governing bodies. To effectively administer the RCUs, most of which, except for the Nairobi Convention RCU, are not located at the UNEP Headquarters, the Director of DEPI, who is in charge of the UNEP Regional Seas Programme, has sub-delegated part of his/her authority to the Heads/Coordinators of the RCUs for some of the administrative and financial management functions. Furthermore, there are also ongoing negotiations between UNEP and the CoPs through their Bureaus89 to adopt agreements on administrative arrangements intended to clarify the relationship and roles between UNEP and the parties on the administrative and financial management of the conventions and the protocols through the RCUs.

10.4.4Regional Activity Centres (RACs)

The sheer number of regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols, plus the various programmes, activities, and projects being executed in different regions to curb the marine environmental challenges clearly demonstrates that the problems are enormous and require concerted measures and actions for solutions. However, the realization of the benefits accruing from the marine and coastal environment have, as a result, necessitated the setting up of Regional Activity Centres (RACs), for most of the UNEP administered and non-UNEP administered RCUs. These RACs are established, hosted, and partly funded by national governments to carry out specific identified regional activities as agreed and approved by different IGMs and CoPs and serve all Member States. Focusing on those for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions, unlike the RCUs, RAC staff members are nationals recruited from and by the host governments. In addition, depending on the labour laws of the Member States, other nationalities from the respective regions may also be considered to work at the RACs.

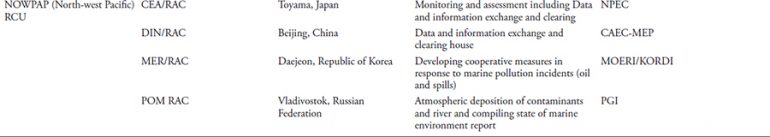

These RACs are normally guided by the IGMs or CoPs and carry out activities for coordination and implementation of activities in support of the action plans, conventions, and protocols at regional, national, and even local levels as approved by the parties. They are generally established under the regional seas action plans and are expected to report directly to the respective and relevant RCU. Appendix 2 shows the Barcelona Convention has the largest number of RACs, six of them, four of which are nationally instituted RACs and one is a UN established centre managed and staffed by International Maritime Organization (IMO) recruited personnel with activities funded by the parties through the RCU. In view of the current financial challenges facing the implementation and management of the Mediterranean Action Plan, its Convention, and Protocols including the RCU, parties at its COP 17 had decided to commission a functional review process90 for the RCU as well as its RACs which led to an extended functional review91 with a refocused and strengthened programme for the RCU.92 Cartagena Convention and NOWPAP have four RACs, each for different marine environment management programmes as shown in Appendix 2.

10.5 Financial Arrangements

The success and sustainability of the Regional Seas Programme is dependent on the availability of adequate financial resources for the implementation of: (i) the priority activities identified in the different regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols, (ii) the growing number of decisions taken by the Members States of the Action Plans during their intergovernmental meetings and/or by the Parties to the different conventions and protocols during their CoPs and (iii) operational costs to run the different established institutional arrangements, such as the RCUs. Although the Regional Seas Programmes have been successful in raising funds from various donors, notably, the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), bilateral, and multilateral donors, amongst others for the different projects and activities on the protection and preservation of the marine environment, difficulties still remain for some regional seas programmes in raising funds from the Member States to manage and run the RCUs. At the adoption of most of the regional seas action plans93 as well as their conventions and related protocols, it was anticipated that and indeed UNEP provided seed funds for the initial phases of the implementation of the regional seas action plans and conventions, as well as the ensuing protocols. This was with an understanding as evidenced in a number of UNEP GC decisions94 that with time the Member States as well as the parties will take full responsibility to fund their programme activities and ensure a financially self-supporting programme. All regional seas action plans have established trust funds financed by, inter alia, assessed contributions from the Member States and parties. For those action plans for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions, management of the trust fund has been entrusted to UNEP to manage and administer them in accordance with the UN/UNEP financial rules and regulations.

Despite UNEP’s willingness to support the initial phases of the implementation of regional seas action plans and its ensuing instruments, unpredictable financial resources for UNEP made it difficult for it to continue to support the RCUs and their programmed activities to the magnitude envisaged, since its funding mechanism is primarily based on voluntary contributions from governments. This, coupled with the ongoing global financial crisis, make it a challenge for UNEP to continue to maintain its generosity in providing financial support to implement the action plans and ensuing instruments.

Unlike for other regional seas instruments, anticipated seed funds for Nairobi and Abidjan instruments with parties primarily from the developing countries were never allocated save for ad hoc projects, a situation which made these instruments begin in a weak position with their management relying heavily on project funds. It is not surprising that the two instruments were for a number of years served by one/joint RCU based at the UNEP headquarters and fully funded by UNEP. UNEP’s dwindling financial resources especially in the 1990s have thus resulted, for instance, in both Abidjan and Nairobi RCUs being centrally and jointly managed for almost over fifteen years by UNEP within the Regional Seas Programme Office at its headquarters. During this period, UNEP covered all of the operational and staff costs while most of their prioritized activities were executed by funds from different donors, since assessed contributions from the parties were either not paid at all or inadequate to sustain independent secretariats for the two conventions.

Even the Twinning Arrangement which linked the Nairobi and Abidjan Conventions with developed regional seas instruments to help reactivate and revitalize these programmes did not lead to the intended success, apart from learning from each other and increasing their profile, but not anticipated resources.95 However, since 2010, through the revitalized process of the regional seas programmes in Africa, the Abidjan Convention RCU re-established itself with its own staff as an independent entity in Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan where it is hosted. The revitalization process, including enhanced political will and commitment of the Parties to both the Nairobi and Abidjan Conventions, is already showing positive results as the contributions including accumulated arrears to the trust funds being paid are currently adequate to sustain the operational cost of the RCUs and some activities, including salaries being fully or partly paid.96 The two secretariats are currently fairly independent, especially the secretariat for the Nairobi Convention, which is being managed and funded by the Parties’ contributions to the secretariat budgets with donors supporting some of their activities.

Although the financial situation for the regional seas programmes in Africa has in the recent years improved drastically, the situation is completely different for the COBSEA or EAS/RCU hosted by UNEP at its Regional Office in Bangkok. UNEP still continues to cover, except for project activities funded by donors, all related core costs for the implementation of the Action Plan including the staff and operations,97 since the agreed levels of voluntary contributions by the Member States had never been adequate to cover all requisite core costs needed to sustain the EAS/RCU. Unfortunately, project-based donor funding does not normally cover secretariat operational costs. The situation was further worsened after Australia withdrew its membership, as its contribution, which was the highest, reduced drastically the level of contributions to the Trust Fund. In the recent years, UNEP has made it clear to the Member States that it can longer continue to fund COBSEA operations and staff costs, urging Member States to take ownership of their secretariat functions and thus take measures to sustain their action plan, including hosting arrangements. At an extraordinary IGM convened by UNEP, Member States reviewed possible options on future management of the COBSEA, its RCU, and hosting arrangement and agreed to increase their assessed contributions as well as their budget by over 120%, from US$155,000 to US$340,000.98 However, as at the time of First Extraordinary IGM held on 19 August 2014, none of the Member States had paid in the increased contribution amount, but at least five Members States had officially confirmed agreement to the increased amount totalling about US$158,000 with a shortfall of US$101,000 of the contributions having been paid.99 Time will tell whether or not the agreements reached will indeed be turned into action and Members States pay the agreed assessed contributions to reach the increased budget and identify an independent host for their EAS/RCU.

On the other hand, NOWPAP Member States, and in particular the governments hosting the RCU in two office locations (Busan, Republic of Korea, and Toyama, Japan) have been discussing possible measures to address financial sustainability of the RCU. The host governments are calling for downgrading of both professional and general service posts in the two locations, but wish to continue to retain the operation of the two offices despite the cost involved in managing and running them.100

In the case of the GPA, unlike the regional seas action plans, conventions, and protocols, its secretariat including its staff is administered, managed, and fully funded by UNEP as it does for its other programmes101 save for donor-funded projects. Through UNEP as its secretariat, GPA is used as a platform to implement all regional seas protocols on land-based sources and activities on marine pollution, developed under the framework of the regional seas conventions.

Despite the initial arrangement and understanding that UNEP would financially support the regional seas action plans during the initial phases, with an undertaking by the Member States to financially self-sustain them, among the UNEP-administered RSPs, only the NOWPAP, CAR, and MAP102 RCUs are currently self-sustaining from their Parties’ assessed contributions with specific projects being funded by donors who in some cases include the Parties themselves, although MAP and NOWPAP have recently also been faced with financial challenges which have caused their governing bodies to reduce the staffing levels and review and re-prioritize their activities as a measure for reducing costs.

10.6 Conclusion—UNEP Regional Seas Programme at Crossroads

Conclusions—Despite many successes and achievements, there are challenges not to be ignored!

10.6.1What has been achieved over the years?

The UNEP Regional Seas Programme (RSP) is currently celebrating its fortieth Anniversary since it was launched in 1974 and over the years it has flourished as one of the major UNEP flagship Programmes for the protection of the regional and shared marine and coastal environment and management of their natural resources for sustainable development.103 The Programme has been guided and promoted by UNEP and has thus grown over the years to currently cover and include 143 participating countries across 13 regions. Most regional seas programmes were modelled and do mirror the 6 regional seas programmes that UNEP provides with secretariat and coordination functions. Taking into account the uniqueness and circumstances of each particular marine region, the Programme succeeded in establishing a working pattern, modality, and approach, that all regional seas conventions and action plans followed similar process for and in their development. This process has been successfully used over the years to launch all regional seas programmes.

A Programme normally began with the development of an action plan (MAP, CAP, WACAF, EAAP, COBSEA and NOWPAP), followed by a legally binding instrument in the form of a framework convention, and simultaneously or thereafter proceeded by associated protocols dealing with specific marine environmental challenges, although there are few of them that have remained as action plans with no framework conventions to date (COBSEA and NOWPAP). Also these RSCAPs have successfully established similar or related functional institutional arrangements or secretariats, namely, Regional Coordinating Units (RCUs), which support, assist, and facilitate implementation of the regional marine instruments. They are mainly hosted by one of the Member States (eg Jamaica for CAP, Greece for MAP, Côte d’Ivoire for WACAF, Japan and Korea for NOWPAP) with only two hosted by UNEP (COBSEA and EAAP). To enhance sustained support and technical assistance for the implementation of the regional instruments, some of the national governments host these Regional Activity Centres (RACs) for the implementation and enforcement of their specific instruments and programmes.

The Regional Seas Programme and the platforms it provides enabled countries with different political settings (Libya/Israel, Iran/Iraq, USA/Cuba, etc) to meet, discuss, and tackle common marine and coastal environment problems or challenges and seek common solutions. As such, the Programme has over the years become a useful unifying factor and a tool for cooperative management of the common natural resources for the benefit of all human beings in their regions, despite any socio-political differences that may exist. In addition, the Programme continues to be a viable platform and avenue not only to support and strengthen regional cooperation, but also a mechanism for the implementation of the global MEAs, such as IMO conventions on marine pollution conventions, chemical MEAs (Basel Convention, Stockholm Convention, and Rotterdam Convention) as well as biodiversity MEAs (CBD, CITES, CMS, WHC, Ramsar Convention), as well as for the GPA, among others. Equally, the Programme continues to provide an effective platform and instruments for supporting implementation and execution of projects funded under the relevant Global Environment Facility (GEF) focal areas or portfolios (eg international waters, biodiversity, chemicals, and land degradation).

For the Regional Seas Programme to succeed the way it has and achieve as illustrated above clearly shows that the needed political leadership at regional level through the participating governments exists. UNEP’s convening power, political leadership, and its influence led to the successful preparations and convening of all key meetings of the Member States for the development and management of a particular regional programme. Equally, financial, intellectual, and facilitative leadership existed and was provided by UNEP through the initial start up, and seed funds were always provided to initiate the consultative negotiation process for the development of the RSCAPs, as mandated and requested by its Governing Council.

Although such financial support was intended to facilitate the negotiation, establishment of the secretariat and initial operations of a convention and/or action plan, it was hoped that UNEP would in the near future hand over responsibility to Member States to manage and sustain the established institutions and operations. It did happen in fact for some RSCAPs (such as, MAP, CAP and NOWPAP, Kuwait Region Action Plan) but not others (eg EAAP, until recent years, COBSEA and WACAF) as UNEP continued for many years to provide full or the majority of their funding needs to sustain their operations.

10.6.2What challenges may limit further successes of the Regional Seas Programme?

Clearly, many notable successes and achievements have been made throughout the period of the existence of the RSP implemented principally through the RSCAPs. Nonetheless and especially in the recent years, the Programme is suffering from its own successes and finds that the challenges faced are increasingly affecting the achievements made over the years, making the Programme a victim of its own success. The principal factors which continue to impact on the successes made over the years and thus affect the current activities of the Programme and its implementation through the RSCAPs are, but not limited to, the expanded Regional Seas programme on one hand and the dwindling financial situation of UNEP since the late 1990s on the other. UN and UNEP reforms and restructuring over the years led to the continued reduction of the number of technical staff responsible for the RSP. The factors in turn continued to impact on the successes made on the achievements of the Programme. Reducing funding for the Programme has affected not only the implementation of the activities in the various regions but also the institutional set up (ie technical and financial capacity) to manage the Programme within UNEP itself.

For instance, up to the 1990s, UNEP’s institutional structure and framework was based on the implementation of thematic programmes through departments in the name of ‘Programme Activity Centres’. The RSP was managed through a fully-fledged centre called, ‘Oceans and Coastal Areas Programme Activity Centre’ (OCA-PAC) led by a Director with the requisite institutional and technical capacity as well as political leadership to manage and steer the Programme. Under this set-up, a number of RSCAPs as well as their related protocols were developed. The weakening of the RSPs can be traced to 1999 when OCA-PAC was replaced by a ‘Water Branch’ in an effort to ensure an integrated approach to the management and protection of both the freshwater and marine resources under one programme. The Water Branch programme did not work, and a weakened Regional Seas programme was placed under the non-legally binding Global Programme of Action (GPA) in The Hague. Under this structure the UNEP administered RSPs Programmes focused on the implementation of GPA, from a top-down perspective with little programmatic attention to the non-UNEP administered Regional Seas Programmes. In the sixteen years of restructuring the Regional Seas Programmes failed to take full advantage of their geographical spread, political reach, and goodwill to lead in the emerging technical areas and debates on oceans governance, and an ecosystems based approach to the oceans management.

The current structure perpetuates the weakening of the Programme. The RSP within UNEP is a small unit within the Freshwater and Marine Ecosystem Management Branch in the Division of the Environmental Policy Implementation. The unit, though not recognized as an independent unit within the Branch, is manned by one professional focal point staff member responsible for monitoring the implementation and management of not only the six RSCAPs for which UNEP provides secretariat and coordination functions and forming part and parcel of its RSP but also doing the same and following up also on the developments taking place under the other twelve non-UNEP administered RSCAPs.

The UNEP’s institutional capacity to manage the RSP is weak, and is construed by outsiders as signs of the dwindling importance of the Programme globally and internally within UNEP. Within the RSCAPs at regional level, contributions by the Parties to a number of their RSCAPs have in many instances been unpredictable and late, resulting in challenges for planned implementation of activities and projects. The inadequate financial resources to effectively support the programmes and activities further reduce the effectiveness of the RSCAPs. The weakened UNEP’s institutional capacity to manage RSPs coupled with reduced contributions from Parties have impacted the effective management, administration, and implementation of the RSCAPs as well as successes and achievements made by the Programme.

Until recent years, implementation and management of the RSCAPs in the developing Africa region, notably, the Abidjan and Nairobi Conventions, were even more affected as a result of the inadequate financial resources both from UNEP as well as contributions from their Parties. Although UNEP as a result of its governing body decision was expected to steer the development of these, like other RSCAPs by providing seed funds for the development of the instruments as well as start-up funds for their operations during the initial years, full financial support for their operations and maintaining the RCUs as well as activities continued for decades until recent years to be funded by UNEP or by donors through UNEP. Unfortunately, the dwindling financial situation of UNEP in the 1990s also adversely affected the level of maintenance and operations of the RCUs for the implementation of the relevant RSCAPs. For instance, the Abidjan Convention entered into force in 1986, and the Nairobi Convention in 1996 but up until around 2001, both instruments did not have a dedicated coordinator, as is the case with all other RSCAPs/RCUs, to support implementation and operations of the conventions save for only one de facto professional officer serving as the focal point for the two instruments due to financial difficulties. Furthermore, the Abidjan Convention never had the CoPs to review the status of the implementation of the instruments for several years, 1986–2001, at times also due to lack of a quorum in addition to financial resources, among other factors.

This situation at least has changed in recent years. Since 2010, the Abidjan Convention has its dedicated RCU formally established at Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire with a dedicated coordinator with a staffing complement. In the years since then, more and more the Parties are taking ownership of their instrument and we have thus seen increasing payments of the agreed assessed financial contributions by the Parties, enabling UNEP to begin to reduce over the coming years its funding support for the coordination of the RCU, and hopefully soon allowing it to be fully owned and managed by the Parties to the Convention and its Action Plan.104

The Nairobi Convention, on the other hand, has had its RCU strengthened and hosted in UNEP since 2002 and within DEPI. The secretariat is managed by a dedicated staff of three with one also managing as the coordinator. With many challenging marine environmental issues which have necessitated the development of these conventions and their related protocols (with some still being negotiated), it is clear that more can be achieved with additional funding resources from the Parties and, as necessary, additional financial and technical support from UNEP. Both the Abidjan and the Nairobi Convention seem to be in a good funding situation, with the Parties taking full responsibility of its RCU operations for the latter and with UNEP beginning to reduce its support for the former to fully managing its affairs in the years to come.

A similar predicament is facing the COBSEA in the South East Asia region, which is currently hosted by UNEP through its Regional Office for Asia and Pacific in Bangkok, Thailand. With limited financial contributions from the Member States (which has not changed for many years) and UNEP supporting the entire operations of the RCU including its staff save for other donor-funded projects, it has become difficult for UNEP to continue to sustain its secretariat, in particular, its coordinator and part-time assistant, who were managing the RCU funded by UNEP.105 The withdrawal from the membership of COBSEA in 2010 by Australia, which was a major contributor to its budget, further weakened its financial base. A recent independent review undertaken by UNEP on the operations of COBSEA revealed that there are other active and better-funded regional bodies in the region which could be considered to take over or merge with COBSEA, such as PEMSEA,106 as a means to reinstate and reinvigorate its operations. Unfortunately, the option of merging with PEMSEA, which is a time-bound GEF funded project which has established itself into an independent regional organization or coordinating mechanism through a Ministerial Declaration,107 may not be a suitable option in the longer term especially after the project ends, unless it is renewed indefinitely which is unlikely.

An extraordinary meeting of the Member States has been held in the recent past to find a solution to the prevailing financial situation of the RCU and its operations.108 Agreement had been reached for each Member State to increase their contribution to the RCU budget for implementation of its activities but no such additional contribution has yet been paid for the purpose.109 Furthermore, in an effort to sustain the operations of COBSEA, Member States had been invited to consider hosting the RCU, including support to its operations, thus having it hosted by a government rather than UNEP. It was anticipated that any such offer would include adequate financial resources to maintain the RCU plus some of its key operational activities. Unfortunately, offers received to date are far from the expectations of other Member States and discussions on the future management, maintenance, and operations of the RCU are still ongoing.110

The situation for NOWPAP and its RCU, which UNEP also provides with secretariat and coordination functions but hosted and fully funded by two governments (Japan and Republic of Korea) of the four Member States (the others are Russia and China) is not encouraging either. Member States failed to agree and approve a budget for its operations at their last Intergovernmental Meeting of the Parties (IGM)111 only to be agreed later on a provisional basis through email exchanges.112 This was soon after followed by an Extraordinary IGM to discuss options for the reduction of costs of operating the two RCUs, one at Toyama, Japan and another at Busan, Republic of Korea while enabling the host Governments to maintain a similar level of their financial contributions for the management and operations of the RCUs.113 Some of the options being considered include reducing the number of staff from both RCU offices and downgrading the levels of some posts while favouring retaining the continuation of the operation of the RCU, including the agreed periodic rotation of the two Coordinators between the two RCU offices. These options have been further debated upon at the 19th NOWPAP IGM held in October 2014 and will be further considered with a final decision to be taken at a scheduled extraordinary IGM in 2015,114 that will also include the outcome of a functional review of the RCU to be carried out in the meantime.115

Implementation of the Barcelona Convention as well as MAP and its RCU also underwent two functional reviews in recent years due to the financial difficulties faced to maintain and support the RCU operations. Some of the recommendations made and already effected include for the first review, amalgamation of some posts with scrapping of some of them and reducing the number of lower cadre staff. The second extended review resulted in downgrading of the senior positions of the coordinator (from D2 to D1 level), deputy coordinator (from D1 to P5 level), downgrading two professional posts (from P4 to P3 and P5 to P3) and abolishing one professional post,116 among other measures.

Unpredictable financial resources are a major factor affecting the smooth operations and implementation of the RCUs and their operational activities, making all the achievements made over the years by the RSP not fully visible and appreciated, as great energy, efforts, and time are spent on identifying solutions to the financial challenges and modalities for their survival, thus impacting on their implementation. Clearly, for the RSCAPs through the RSP to be further enhanced, maintained, and effectively implemented, prerequisites like political will which in turn supports and ensure the financial base of the Programme, a solid legal base, sound and effective institutional structures, realistic implementation of the regional programme, efficient and effective RCUs with adequate financial and human resources are conditio sine quo non for their successful survival. Financial resources will therefore remain a challenge both for UNEP to continue to maintain its financial support to the RSP as well as the Parties and Member States to the RSCAPs to ensure their RSP and its instruments are self-sustaining.

REGIONAL SEAS CONVENTIONS, ACTION PLANS AND PROTOCOLS

Note:

MAP – Mediterranean Action Plan

WACAF – West and Central African

CAP – Caribbean Action Plan

EAAP – East African Action Plan

NOWPAP – Northwest Pacific Region

COBSEA – Coastal Areas for East Asian Region

ROPME – Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment

PERGSA – Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

SASAP – South Asian Seas Region

OSPAR – The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the ‘OSPAR Convention’) opened for signature at Oslo and Paris in 1992

HELCOM – Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission—Helsinki Commission which is the governing body of the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area

PAME – Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment

CCAMLR – Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

CAMLR – Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources of 1980

HW – Hazardous Wastes

PAs – Protection Areas

WFF – Wild Fauna and Flora

TB – Transboundary

E&E of CS – Exploration and Exploitation of Continental Shelf

ICZM – Integrated Coastal Zone Management

EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment

SPAs – Special Protected Areas

SPAW – Special Protected Areas and Wildlife