Qiwāma in Egyptian Family Laws: ‘Wifely Obedience’ between Legal Texts, Courtroom Practices and Realities of Marriages

Part I

Perspectives on Reality

QIWĀMA IN EGYPTIAN FAMILY LAWS

‘Wifely Obedience’ between Legal Texts, Courtroom Practices and Realities of Marriages

Mulki Al-Sharmani

Egyptian Muslim family laws (known as personal status laws) were codified in 1920.1 Personal Status Law No. 25 of 1920 and its amendments (i.e. Law No. 25 of 1929 and Law No. 100 of 1985) were largely drawn from the doctrines of classical Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) through a process of selection, modification and patching together of different legal opinions of classical jurists. Some well-known historians, who have studied this process and the earlier, pre-codification legal system of Shariʿa Courts, argue that codification has, for the most part, worked against Egyptian women.2 These scholars contend that although the old legal system of fiqh manuals and Shariʿa Courts – presided over by religiously trained judges from different schools of Islamic law – espoused a patriarchal model of marriage, its legal pluralism, fluidity and decentralised judicial process still enabled women to have choices, to exercise agency and to enjoy protection from the abuses of the doctrinally sanctioned patriarchy.

Thus, Egyptian women’s rights activists, from the 1920s until the present day, have engaged in various efforts to reform the codified personal status laws. Some of the main problem areas in the existing personal status laws for present-day activists seeking gender justice are unequal parenting rights and men’s right to unilateral repudiation and polygamy, both of which men can exercise without resorting to the court. While men have almost unconditional divorce rights, women have restricted access to limited types of divorce that can only be obtained through court. According to current family laws, a wife can file for fault-based judicial divorce on six grounds, namely non-maintenance, absence, defect, harm, the husband’s polygamy and imprisonment. In fault-based judicial divorce, a female litigant has to provide to the court proof of spousal fault and often undergoes a long and costly legal process. Moreover, even when women win such cases, court judgments can be appealed by husbands. In 2000, women were granted the right to no-fault divorce known as khulʿ. Yet women still have to seek khulʿ through a lawsuit, undergo courtordered arbitration and forfeit their post-divorce financial dues.

Another contentious area in the current family code is that it stipulates and upholds men’s right to wifely obedience, which is linked to the notion of the husband’s qiwāma (i.e. guardianship) over his spouse. In this chapter, I will examine how qiwāma (men’s obligation to protect, provide and guard their family) is constructed in Egyptian substantive family codes,3 and how this legal construction is implemented in courtroom practices. My goal is to explore the ways in which this legal concept shapes women’s rights in marriage and how it impacts women’s claims and strategies in the courtroom.4 I wish to shed light on the ways in which existing laws on qiwāma are implicated in the hierarchical and discriminatory model of marriage that Egyptian reformers are seeking to change.5 Qiwāma will be examined through the laws regulating the husband’s obligation to provide for his wife and the latter’s legal duty to obey him.

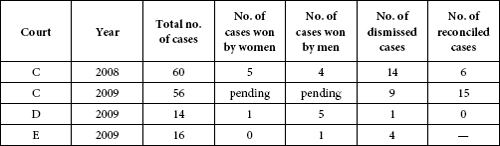

The analysis in this chapter draws on data collected from interviews with 30 male and female plaintiffs (15 of each gender) in obedience cases, a focus group discussion with ten lawyers and observation of court proceedings in a Giza court.6 In addition, statistical data on obedience cases were collected from five family courts in the governorates of Giza, Cairo and Sixth of October for the periods 2001 to 2009, and 30 court judgments were analysed. Finally, this chapter also draws on data collected from interviews with 100 Egyptian men and women (50 of each gender). These interviews focused on informants’ marriage choices and marital roles, as well as their knowledge of recent reforms in family laws. Interviewees of different marital statuses were selected.7

1. Qiwāma in Islamic jurisprudence and Egyptian family laws

Islamic fiqh constructs marital roles in terms of a husband’s qiwāma (i.e. authority and protection) over his wife and the latter’s obedience (ṭāʿa) to him.8 This construction is based on early jurists’ interpretation of the following Qurʾanic verse:

Men are the protectors (qawwāmūn) and maintainers of women because God has given the one more strength (faḍḍala) than the other and because they support them from their means. Therefore the righteous (qānitāt) women are devoutly obedient and guard in the husband’s absence what God would have them guard. As to those women on whose part ye fear disloyalty and ill-conduct, admonish them first. Next, refuse to share their beds. And last beat them lightly; but if they return to obedience, seek not against them means of annoyance (4:34, Yusuf Ali’s translation).9

Therefore, a husband has a duty to provide for his wife, and in return the wife makes herself available to him, and puts herself under his authority and protection. The husband’s exclusive right to his wife’s sexual and reproductive labour is acquired through and conditioned upon his economic role. This model of marriage does not recognise shared matrimonial resources. Whatever possessions and assets the wife brings to the marriage remain hers. Likewise, apart from maintenance for herself and her children, the wife cannot make claims to resources acquired by the husband during marriage. In addition, the husband has unilateral right to repudiation and polygamy.

Marriage in modern Egyptian family laws reflects some of the main features of fiqh-based marriage. Article 1 in Egypt’s Personal Status Law No. 25 of 1920 (amended by PSL No. 25 of 1929 and PSL No. 100 of 1985) stipulates that ‘maintenance shall be the wife’s right and due on her husband from the authentic date of the contract if she shall have given herself to him in marriage even if virtually and despite her being wealthy or different from him in religion’. Thus, marital roles are also defined as the husband being a provider for his wife, while the role of the latter is to be sexually available to the husband. To fulfil this role, the wife is expected to be ‘obedient’ to her husband. The code defines wifely obedience indirectly by defining its opposite, namely disobedience or nushūz. Article 11 in the code stipulates that ‘if the wife refrains from obeying the husband unjustifiably and without any right, the wife’s alimony shall be discontinued from the date of disobedience’. The article adds that ‘a wife shall be considered refraining from obedience to her husband if she does not return to the matrimonial house after her husband calls her to return by serving on her person or on her proxy, a notice via a bailiff. He shall indicate the location of the matrimonial house in this notice.’ Thus, the code defines wifely disobedience (nushūz) as a wife’s illegitimate refusal to reside in the matrimonial house. Moreover, a wife who is found to be disobedient (nāshiz) by the court loses her right to spousal maintenance.

Among the legitimate grounds that permit a wife to leave the matrimonial home and thus entitle her to contest her husband’s ordinance for her obedience are: (1) if the husband has not paid her the prompt dower (mahr), (2) if the matrimonial house is not safe or adequate, (3) if the husband does not protect her or her money (e.g. abuses her and/or unlawfully takes her money or possessions), or (4) if her leaving the matrimonial house is for reasons sanctioned by the social norms (ʿurf). However, the law does not spell out what these reasons are. But it is commonly understood that some of the acceptable reasons would include leaving the matrimonial house to visit extended family or to seek education or health care. However, whether a wife’s leaving the matrimonial house for work is considered a socially acceptable reason has been contested by litigants and judges. But the explanatory memorandum of PSL No. 100 of 1985 points out that in the case when a wife has written in her marriage contract that she holds a job, her husband cannot bring an obedience-ordinance case against her on the basis of her going out to work. It is noteworthy that up until 1967, a wife who was found to be disobedient by the court faced the threat of forcible return to the conjugal home by law enforcement officials should her husband so wish. Nowadays, while the forcible return of a disobedient wife to the matrimonial house has been abolished, her loss of spousal maintenance remains sanctioned by the law.

But how do these legal marital roles, which obligate a husband to be a provider for his wife in exchange for her obedience, actually work in court cases on the one hand, and in the real marriages of Egyptian couples on the other?

2. Courtroom practices and realities of marriage: obedience ordinances

To initiate an obedience-ordinance case, a husband needs to file for a claim with the court bailiff who then sends a notice to his wife. The notice should specify the matrimonial house where his wife is supposed to fulfil her role of residing and being physically available for her husband (iḥtibās al-zawja). The wife then has the legal right to contest the obedience ordinance within a period of 30 days from the time she has been served the notice. However, if the wife fails to contest the obedience ordinance within the defined period of time, the husband does not automatically win the obedience case. The next step for him is to file for a proof-of-nushūz case. And it is only after the husband wins this latter case that a wife loses her right to spousal maintenance. On the one hand, one could argue that this somewhat prolonged legal process seems to protect wives from an easy loss of their right to spousal maintenance. On the other, there are a number of ways in which husbands exploit the system to their advantage and to the detriment of the wife. For instance, it is not uncommon for husbands to have obedience ordinances sent to wrong addresses so that their wives do not receive them and thus fail to contest them within due time. In addition, in the new family court system, every family dispute case (including contesting an obedience ordinance) has to first go through mandatory pre-litigation mediation.10 In theory, when a wife files for pre-litigation mediation, the filing should count as the beginning of her lawsuit to contest the obedience ordinance. But recent studies have reported that some judges do not consider the filing for mediation as constituting the plaintiff’s fulfilment of the condition of contesting the obedience ordinance within the designated 30-day period.11 Of course, the most obvious challenge that a wife faces in such a case is that she has to prove to the court the legitimacy of the grounds on which she is contesting the ordinance. But how do wives contest obedience ordinances? And is it difficult for them to establish legitimate grounds for their contestations? To answer this question, it is first necessary to shed light on the reasons why men file for obedience ordinances and why women contest them.

3. Reasons for filing for obedience cases and contesting them

The field data collected for this chapter show that husbands and wives use obedience cases for a variety of reasons that may or may not be directly related to the case itself. For instance, a husband may file for an obedience ordinance to offset a wife’s efforts to seek judicial divorce; to negotiate for more advantageous financial settlement as the wife seeks judicial divorce; to respond to a maintenance claim, or as a preemptive legal tactic before the wife files for such a claim; or to affirm his position of power and authority before he negotiates (through legal and non-legal channels) for the return of his wife to the matrimonial home.

Most of the women who are served obedience ordinances from their husbands feel compelled to contest the ordinance. Their motivations, however, are diverse and go beyond protecting their right to maintenance. Some of these reasons include: facilitating their pursuit of divorce, claiming a matrimonial house that is separate from the dwelling of the in-laws and negotiating their right to work.

Some women leave the matrimonial house and are either considering or have started the process of seeking judicial divorce. These women (and their lawyers) believe that successfully contesting the obedience ordinance would strengthen their legal position in the divorce case. One of the main and common grounds on which a wife wins the contestation of an obedience ordinance is the husband’s failure to protect her and/or her money. Proving the husband’s failure to protect his wife means establishing that harm is inflicted on the wife, which improves the latter’s chances of winning the divorce case. Interestingly, women who are seeking khulʿ are sometimes disputants in obedience-ordinance cases. This happens either because the husband files for obedience after the wife has filed for khulʿ, or because the wife files for khulʿ while in the process of the obedience lawsuit. What often happens in a number of these cases is that the wife first gets a khulʿ judgment, and, accordingly, wins the contestation of the obedience case on the grounds that a divorced wife does not owe ‘obedience’ to her husband. The following cases demonstrate how an obedience lawsuit evolves into divorce.

Case 1: Obedience and khulʿ