PUBLIC ORDER OFFENCES

Public order offences

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of the offences of riot, violent disorder and affray

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of the offences of riot, violent disorder and affray

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of other offences created by the Public Order Act 1986

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of other offences created by the Public Order Act 1986

Analyse critically offences under the Public Order Act 1986

Analyse critically offences under the Public Order Act 1986

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether there is criminal liability for an offence under the Public Order Act 1986

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether there is criminal liability for an offence under the Public Order Act 1986

The main public order offences are now contained in the Public Order Act 1986, though there are other offences, for example wearing a uniform for a political purpose under the Public Order Act 1936, and aggravated trespass under s 68 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

The Public Order Act 1986 abolished the old common law offences of riot, rout, unlawful assembly and affray and created three new offences in their place. These are riot, violent disorder and affray. The law has been made more coherent, with common themes of using or threatening unlawful violence, and conduct which would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety.

Although these offences are aimed at maintaining public order, the Act states that all three offences can be committed in private as well as in a public place.

17.1 Riot

This is an offence under s 1 of the Public Order Act 1986:

SECTION

1(1) Where twelve or more persons who are present together use or threaten unlawful violence for a common purpose and the conduct of them (taken together) is such as would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety, each of the persons using unlawful violence for the common purpose is guilty of riot.

(2) It is immaterial whether or not the twelve or more use or threaten unlawful violence simultaneously.

(3) The common purpose may be inferred from conduct.

(4) No person of reasonable firmness need actually be, or likely to be, present at the scene.

(5) Riot may be committed in private as well as public places.’

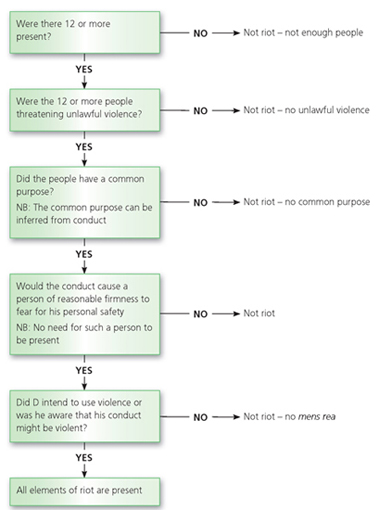

17.1.1 The actus reus of riot

This has several elements. It requires:

at least 12 people to be present together with a common purpose

at least 12 people to be present together with a common purpose

violence to be used or threatened by them

violence to be used or threatened by them

so that the conduct would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety

so that the conduct would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety

The 12 or more people need not have agreed to have assembled together; the fact that they are there together is the key point. The common purpose need not have been previously agreed. As s 1(3) states, the common purpose can be inferred from the conduct of the 12 or more people. This covers situations where a number of people come to the scene (whether together or one by one) and then because of an incident involving one person (perhaps being arrested by the police), 12 or more of the people there start threatening the police. All those threatening or using violence will then be guilty of riot.

The offence of riot can be committed even if the common purpose is lawful, for example employees want to discuss redundancies with their employer. But if 12 or more of them use or threaten unlawful violence they may be guilty of riot.

Violence

The meaning of ‘violence’ is explained in s 8 of the Act:

SECTION

‘8 …(i) except in the context of affray, it includes violent conduct towards property as well as violent conduct towards persons, and

(ii) it is not restricted to conduct causing or intended to cause injury or damage but includes any other violent conduct (for example, throwing at or towards a person a missile of a kind capable of causing injury which does not hit or falls short).’

Only unlawful violence can create riot. If the violence is lawful, for example in prevention of crime, or self-defence, then there is no offence.

17.1.2 mens rea of riot

Section 6(1) states the mental element required for the offence:

SECTION

‘6(1) A person is guilty of riot only if he intends to use violence or is aware that his conduct may be violent.’

So from this it can be seen that intention or ‘awareness’ is the mental element. Intention has the normal meaning in criminal law. However, awareness is a new concept. It has some similarity to Cunningham (1957) recklessness (see Chapter 3, section 3.3) as it is a partly subjective test: the defendant must be aware that his conduct may be violent. But it is not fully subjective as it does not require the defendant to be aware that it is unreasonable to take the risk that his conduct may be considered violent or threatening.

Section 6 also has a subsection specifically on the effect of intoxication on a defendant’s mens rea. Section 6(5) states that:

SECTION

‘6(5) For the purposes of this section a person whose awareness is impaired by intoxication shall be taken to be aware of that which he would be aware if not intoxicated, unless he shows either that his intoxication was not self-induced or that it was caused solely by the taking or administration of a substance in the course of medial treatment.’

This makes riot a basic intent offence. However, unlike other basic intent offences, it puts the onus of proving that the intoxication was involuntary on the defendant.

I ntoxication is defined in s 6(6) as ‘any intoxication, whether caused by drink, drugs or other means, or by a combination of means’.

17.1.3 Trial and penalty

Riot is viewed as a serious offence and has to be tried on indictment at the Crown Court. The maximum penalty is imprisonment for 10 years. Riot is regarded as serious because there is criminal behaviour by a large group of persons.

17.2 Violent disorder

This is an offence under s 2 Public Order Act 1986:

SECTION

2(1) Where three or more persons who are present together use or threaten unlawful violence and the conduct of them (taken together) is such as would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety, each of the persons using or threatening unlawful violence is guilty of violent disorder.

(2) It is immaterial whether or not the three or more use or threaten unlawful violence simultaneously.

(3) No person of reasonable firmness need actually be, or likely to be, present at the scene.

(4) Violent disorder may be committed in private as well as public places.’

17.2.1 Present together

As can be seen from s 2(1) above, one of the requirements for the actus reus of violent disorder is that three or more persons must be present together. The meaning of ‘present together’ was considered in NW (2010) EWCA Crim 404.

CASE EXAMPLE

NW (2010) EWCA Crim 404

A friend of NW dropped litter and was asked to pick it up by a police officer. The friend did pick it up but then dropped it again. The police officer asked her to pick it up again and when she failed to do so, the police officer took hold of her arm. NW intervened and held on to her friend’s jacket. The incident escalated into violence with NW using violence toward the police, and a crowd gathering some of whom also threatened or used violence towards the police. The defendant and two others were charged with violent disorder and convicted.

On appeal, the defence argued that although there did not need to be a common purpose, there must be some degree of conscious participation or cooperation with others or at least some foresight that more widespread disorder might result from his or her actions.

The Court of Appeal rejected this argument and held that the offence was committed when three persons were present threatening or using violence. The expression ‘present together’ meant no more than being in the same place at the same time. They pointed out that three or more people threatening or using violence in the same place at the same time is a daunting prospect for other people who may be there. It makes no difference whether the threat or use of violence is for the same purpose or a different purpose. The court also pointed out that sections 1 (riot), 2 (violent disorder) and 3 (affray) in the Public Order Act 1986 were all aimed at public disorder of a kind which would cause ordinary people at the scene to fear for their safety.

The decision in NW (2010) stresses the fact that no common purpose is needed for the offence of violent disorder.

17.2.2 Mens rea of violent disorder

Under s 6(2) of the Public Order Act 1986, the mens rea required is that D intends to use or threaten violence or be aware that his conduct may be violent or threaten violence. The same rule on intoxication under s 6(5) of the Act that applies to riot also applies to violent disorder. So violent disorder is a basic intent offence. If D claims that the intoxication was involuntary, then the burden of proving this is on the defendant.

17.2.3 Comparison with riot

Most of the elements are the same as for riot. The similarities are the following:

The people must be present together.

The people must be present together.

They must use or threaten unlawful violence so that their conduct would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety.

They must use or threaten unlawful violence so that their conduct would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety.

The violence can be to a person or to property.

The violence can be to a person or to property.

It can be in either a public or a private place.

It can be in either a public or a private place.

There must be intention to use violence or awareness by D that his conduct may be violent. This is specifically stated in s 6(2) of the Act.

There must be intention to use violence or awareness by D that his conduct may be violent. This is specifically stated in s 6(2) of the Act.

Section 6(5) applies to both riot and violent disorder, so violent disorder is also a basic intent offence and D has to prove that any intoxication was involuntary.

Section 6(5) applies to both riot and violent disorder, so violent disorder is also a basic intent offence and D has to prove that any intoxication was involuntary.

tutor tip

The differences are

There need only be three people involved (although it can be charged where there is a greater number of persons involved — even where there are 12 or more).

There need only be three people involved (although it can be charged where there is a greater number of persons involved — even where there are 12 or more).

There is no need for a common purpose.

There is no need for a common purpose.

17.2.4 Trial and penalty

Violent disorder is regarded as less serious than riot. It is intended to be used where fewer people are involved or for less serious happenings of public disorder. This can be seen by the fact that it is triable either way (though in most cases it is tried on indictment). Where it is tried on indictment, the maximum penalty is imprisonment for five years.

17.3 Affray

This is an offence under s 3 Public Order Act 1986:

SECTION

3(1) A person is guilty of affray if he uses or threatens unlawful violence towards another and his conduct is such as would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety.

(2) If two or more persons use or threaten unlawful violence, it is the conduct of them taken together that must be considered for the purposes of subsection (1).

(3) For the purposes of this section a threat cannot be made by the use of words alone.

(4) No person of reasonable firmness need actually be, or likely to be, present at the scene.

(5) Affray may be committed in private as well as public places.’

17.3.1 Actus reus of affray

For this offence there has to be

use or threat of violence towards another person; and

use or threat of violence towards another person; and

conduct which would cause a reasonable person present at the scene to fear for his safety.

conduct which would cause a reasonable person present at the scene to fear for his safety.

Use or threat of violence towards another person

There must be someone present at the scene, as the use or threat of unlawful violence must be against a person. (This is different to riot and violent disorder.) The point was decided in I, M and H v DPP (2001) UKHL 10.

CASE EXAMPLE

I, M and H v DPP (2001) UKHL 10

All three Ds were members of a gang. They had armed themselves with petrol bombs which they intended to use against a rival gang. Before the rival gang came on the scene, the police arrived, and the group (including the three Ds) threw away their petrol bombs and dispersed. The stipendiary magistrate found that there was no one present apart from the police. There was no threat to the police because the moment they arrived, the gang dispersed. The House of Lords quashed their conviction, as affray can only be committed where the threat was directed towards another person or persons actually present at the scene.

Lord Hutton in his judgment pointed out that the defendants should have been charged under s 1 of the Prevention of Crime Act 1953 or s 4 of the Explosive Substances Act 1883.

Conduct

The threat cannot be made by words alone, even if the words are very threatening and the tone of voice aggressive. There must be some conduct. In Dixon (1993) Crim LR 579, the Court of Appeal upheld D’s conviction for affray where the police had been called to a domestic incident. When they got there D ran away, accompanied by his Alsatian-type dog. The police officers cornered him and he encouraged the dog to attack them. Two officers were bitten before extra police arrived, and D was arrested. Encouraging the dog to attack was held to be conduct.

Person of reasonable firmness

Section 3(4) states that it is not necessary for a person of reasonable firmness to have been at the scene. This point was illustrated in Davison (1992) Crim LR 31, where the police were called to a domestic incident. D waved an eight-inch knife at a police officer saying ‘I’ll have you’. The Court of Appeal upheld his conviction for affray. It was not a question of whether the police officer feared for his personal safety. The test was whether a hypothetical person of reasonable firmness who was present at the scene would have feared for his personal safety.

The offence of affray is a public disorder offence designed for the protection of the bystander. In R (on the application of Leeson) v DPP (2010) EWHC 994 Admin, the court had to consider a purely domestic incident.

CASE EXAMPLE

R (on the application of Leeson) v DPP (2010) EWHC 994 Admin

D, who had a history of irrational behaviour, lived with V. D, while holding holding a knife, walked into the bathroom of their home where V was taking a bath. She was very calm and said ‘I am going to kill you’. V did not believe that she would use the knife and easily disarmed her. The magistrates convicted D of affray on the basis that, although the chance of anyone arriving at the house while D was holding the knife was small, it could not be discounted. The Divisional Court allowed D’s appeal as on the evidence they did not think that any bystander would have feared for his own safety.

In her judgment Rafferty J reviewed earlier cases, in particular the case of Sanchez (1996) Crim LR 527 where D had tried to attack her former boyfriend with a knife outside a block of flats. V deflected the blow and ran. The Court of Appeal quashed her conviction for affray as the violence was merely between the two individuals, and as it was outdoors in an open space, there was ample opportunity for any bystander to distance himself from the violence. Thus, there was no real possibility that any bystander would fear for his personal safety.

17.3.2 Mens rea of affray

The defendant is only guilty if he intends to use or threaten violence or is aware that his conduct may be violent or threaten violence. This is the same rule as for violent disorder (s 6(2) of the Act). Like riot and violent disorder, affray is also a basic intent offence, and the same rule also applies of the onus being on the defendant to prove that any intoxication was involuntary (s 6(5)).

17.3.3 Trial and penalty

Affray is triable either way, but it is usually tried summarily at a magistrates’ court. If it is tried on indictment then the maximum penalty is three years imprisonment.

KEY FACTS

Key facts on riot, violent disorder and affray

| Riot |