Proving Costs and Damages

Chapter 18

Proving Costs and Damages

The issue in construction disputes that generally receives the most attention is liability. Does a differing site condition exist? Who caused the delay, and is it compensable? But the issue of damages (or cost flowing from the events giving rise to liability) is no less important. Too often calculating costs and proving damages takes a backseat, with little precision or scrutiny applied until late in the dispute resolution process. That approach can result in an entirely misguided claim effort, missed opportunities for settlement, and loss at trial or in arbitration. The inability to prove damages with a reasonable degree of certainty may prevent the claimant from recovering the full amount, or even a substantial portion, of the damages to which it may be entitled. An early and realistic analysis of damages can help determine whether a claim really exists and the best means of preparing and positioning the claim for the affirmative recovery sought.

I. Basic Damage Principles

A. The Compensatory Nature of Damages

Several basic premises underlie the theory of damages. For example, when a claimant seeks to recover damages resulting from another party’s breach of contract, the court generally will attempt to put the claimant in the same position it would have been in had the contract been performed by all parties according to its terms.1 This theory of the measure of damages applies to all breach of contract actions, not just those arising from construction contracts.2 The law of contract damages is compensatory in nature and, as such, is designed to reimburse the complaining party for all “losses caused and gains prevented” by the other party’s breach.3

In contrast, the goal in a tort (non-contractual wrong) case is to put the injured party in the same position it would have been in had the tort not been committed.4 In the construction area, tort claims generally are asserted for negligence, misrepresentation, and, in rare cases, on the basis of strict liability.5 Computation and proof of tort damages are often complex, requiring an evaluation of the foreseeability of the injury and the possible contributory or comparative negligence of other parties, or assumption of risk by a party. Although tort damages may be broader in scope than contract damages, many courts limit tort damages to cases involving either personal injury or property damage, and deny recovery for purely economic loss.6 For these reasons, and because most construction claims are based primarily on a breach of contract, this section focuses on the computation of breach of contract damages.

B. Categories of Damages

Damages resulting from breach of a construction contract are generally of two basic types: direct and consequential. Although it may be difficult to determine the category within which a claimant’s damages fit, the increased use of damage waivers in contracts has made this analysis more important than ever. Specifically, both the 1997 and 2007 versions of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) A-201 General Conditions and the 2014 version of ConsensusDocs 200 contain a waiver by both the owner and the contractor of consequential damages.7 Therefore, before deciding whether to execute a contract containing such a clause, one will certainly need to be familiar with the type of damages included within the waiver.

1. Direct Damages

Direct damages, sometimes referred to as general damages, are those that result from the direct, natural, and immediate impact of the breach, and are recoverable in all cases where proven.8 A contractor’s direct damages may include idle labor and machinery, material and labor escalations, labor inefficiency, extended jobsite general conditions, and home office overhead. The owner’s direct damages generally are those costs incurred in completing or correcting the contractor’s work and the cost of delay, which is either its actual cost in terms of lost rent or loss of use, or liquidated damages.

2. Consequential Damages

The second category of contract damages is consequential damages, sometimes referred to as special damages. Consequential damages do not flow directly from the alleged breach but are an indirect source of loss. In order to be included within the claimant’s recovery, consequential damages must have been within the contemplation of the parties, or flow from special circumstances attending the contract known to both parties, when the contract was executed. These losses, which are related only indirectly to the breach, may include loss of profits or a loss of bonding capacity. The most frequently sought types of consequential damages are lost profits, interest on tied-up capital, and damage to business reputation. Both owner and contractor will most often seek these types of consequential damages in connection with delay claims.

These are more difficult to prove, because the causal link between such damages and the act constituting the breach may be tenuous and uncertain.

Recovery of consequential damages for breach of contract requires proof of several things: (1) the consequence was foreseeable in the normal course of events; (2) the breach is a substantial causal factor in the damages; and (3) the amount of the loss can be reasonably ascertained.9 The first element is satisfied by showing the particular type of injury was reasonably foreseeable to the other party at the time of contracting. The “reasonably foreseeable” test was originally enunciated in the English case of Hadley v. Baxendale10 and has since been widely adopted by American courts.11

The second element the claimant must prove is that the damages flowed “naturally” or “proximately” from the breach.12 In lay terms, this means the injury must be the result of the breach rather than some other cause.

The third limitation on the recovery of consequential damages is that the damages sought must not be too remote or speculative.13 This general requirement is frequently codified under state law. Questions and issues of the “remote and speculative” nature of claimed damages frequently arise when a claimant seeks to recover profits that have allegedly been lost as a result of the breach—for example, as a result of tied-up capital or reduced bonding capacity. Although statutes covering consequential damages may require “exact computation,” most courts have taken a somewhat less stringent approach. The court in one such case explained:

[T]he pecuniary amount of consequential damages need only be proven with reasonable certainty and not absolute precision. Once a defendant has been shown to have caused a loss, he should not be allowed to escape liability because the amount of the loss cannot be proved with precision. Consequently, the reasonable level of certainty required to establish the amount of a loss is generally lower than that required to establish the fact or cause of a loss. The certainty requirement is met as to the amount of lost profits if there is sufficient evidence to enable the trier of fact to make a reasonable approximation. What constitutes such an approximation will vary with the circumstances. Greater accuracy is required in cases where highly probative evidence is easy to obtain than in cases where such evidence is unavailable.14

In seeking consequential damages, the claimant assumes a much heavier burden of proof as compared to direct damages. Moreover, many contracts, and particularly public construction contracts, by their terms exclude claims for consequential damages.15

3. Punitive Damages

Punitive damages are awarded where there is evidence of oppression, malice, fraud, or wanton and willful conduct on the part of the defendant, and are above what would ordinarily compensate the complaining party for its losses. These damages are not compensatory in nature but rather are intended to punish the defendant for its wrongful behavior or to make an example in order to deter others from similar conduct.16 Many jurisdictions refer to punitive damages as exemplary damages and define them similarly. California defines punitive or exemplary damages as “damages other than compensatory damages which may be awarded against a person to punish him for outrageous conduct.”17

Traditionally it has been held that punitive damages are not recoverable in an action for breach of contract, absent proof of fraud or malicious intent.18 This is generally so even if the breach is intentional.19 In some states, however, the courts may permit the award of punitive damages where there is sufficient evidence of “malice” or utter disregard for the rights of others so as to constitute a willful and wanton course of action, or other tortious conduct amounting to fraud.20 Additionally, some states allow for recovery of punitive or exemplary damages through their unfair trade practice statutes, many times referring to them as “treble damages.”21 Finally, expenses of litigation may be allowed as damages in an action for breach of contract, if specifically allowed for under the contract or if provided by statute.

C. Causation

In order to prosecute a claim successfully, a claimant must establish the liability of the other party and the amount of its own damages, and prove the damages were caused by the acts giving rise to liability. It is essential that the claimant demonstrate causation, meaning the damages presented flow directly or indirectly from the liability issues presented. Without making this link, even the most thoroughly prepared and well-documented construction claim will not be able to withstand competent attack. It is not essential to establish the extent of the damage with absolute certainty if there is no question as to the fact damage did occur.22 Again, although speculative damages are not recoverable, the courts generally recognize that there is a difference in the measure of proof needed to show the claimant sustained damage and the measure of proof needed to fix those damages.

D. Cost Accounting Records

The availability of proper cost accounting techniques when the claim is identified can substantially reduce the problem of calculating and proving damages. In fact, utilizing such techniques consistently may even help in the early identification of a potential claim if the actual recorded costs vary from the anticipated costs. Accounting measures can be established to segregate and carefully maintain separate records. If such a procedure is followed, proof of damages may be reduced to little more than the presentation of evidence of separate accounts. Unfortunately, this ideal situation seldom exists; either the problem is not recognized in time to set up separate accounting procedures, the maintenance of separate accounts is simply not possible because of an inability to isolate costs, or no attempt is made to establish the requisite procedures. These circumstances necessitate the development of some formula sufficiently reliable to permit the court or arbitrators to allow its use as proof of damages.

E. Mitigation of Damages

In a breach of contract action, the amount of recovery generally is limited to those losses and damages caused by the breach that are considered unavoidable.23 The complaining party may not stand idly by and allow the losses to accumulate and increase, when reasonable effort or cost could have reduced the losses. This requirement is known as the duty to mitigate damages. In construction cases, it usually arises where, upon a breach by one of the parties, there is a need for protection of partially completed work, timely reprocurement, assignment of equipment or work crews, or reduction of delay costs. In particular, an owner that makes no effort to obtain a reasonable contract price upon reprocurement on a defaulted project cannot expect to recover the full difference between the original contract and the increased cost to complete.24

The duty to mitigate damages calls for reasonable diligence and ordinary care. The party’s actions need only be reasonable under the circumstances.25 The law does not require that the defaulted party undertake extraordinary expense or effort to avoid losses flowing from a breached contract.26

F. Betterment

A related concept holds a party cannot expect compensation for more than the loss arising from a breach of contract. For example, necessary repairs or replacement of a structure may, in fact, provide the owner with a “better” building than provided for in the plans and specifications.27 In such instances, where the owner obtains a “betterment” from the efforts of the contractor, any award of damages for breach must be reduced by the value of the betterment the owner receives.28

G. Economic Loss Rule

Economic losses involve injury to a financial or business interest as distinguished from losses involving personal injury or injury to property.29 The economic loss rule is a judicially created doctrine that sets forth the circumstances under which a tort action is prohibited if the only damages suffered are economic losses.30

The origins of the economic loss rule may be traced to the California decision Seely v. White Motor Co., where the court addressed a truck purchaser’s products liability action for economic damages to the truck itself resulting from defects, with no personal injury or damage to other property.31 The court held that the truck manufacturer should be liable for economic losses based on its agreement or warranty with the purchaser and not liable in tort. To permit a plaintiff to recover for purely economic loss outside the context of a contract or warranty could result in the manufacturer being liable for “damages of unknown and unlimited scope.”32

The economic loss rule developed as a way to maintain a distinction between contract and tort law; to enforce expectancy interests of the parties so that they can reliably allocate risks and costs during their bargaining; and to encourage the parties to build the cost considerations into the contract because they will not be able to recover economic damages in tort.33

The application of the economic loss rule varies significantly by state. In its most common form, the economic loss rule bars tort claims if the dispute is the subject of an existing contract.34 However, the rule may apply where parties do not have a contract.35 Numerous exceptions to the economic loss rule also exist, thus allowing a party to recover economic losses despite the economic loss rule, including situations where a party is a third-party beneficiary,36 where parties have relationships that are the functional equivalent of privity37 or otherwise “special,”38 and where tort claims are based on violations of building codes,39 negligent misrepresentation,40 tortious interference with contract,41 or fraud.42

II. Methods of Pricing Claims

There are several basic methods for pricing construction claims. The simplest method is the total cost method. The over-simplicity of the total cost method causes it to be frowned on and accepted only in extreme cases. The modified total cost method attempts to address those weaknesses but still faces similar criticisms. Another more complicated, but more widely accepted, method is the discrete or segregated cost method. Finally, there is the quantum meruit approach to pricing a claim, which ignores costs and focuses instead on the value of the material and services provided.

A. The Total Cost Method

A total cost claim is simply what the name implies. It essentially seeks to convert a standard fixed-price construction contract into a cost-reimbursement arrangement. The contractor’s total out-of-pocket costs of performance are tallied and marked up for overhead and profit. Payments already made to that contractor are deducted from that amount, and the difference is the contractor’s damages. This approach can be refined or adjusted to meet particular needs and circumstances, but the basic components and approach remain: Costs associated with the basis for the claim are not segregated. The total cost method often is used for impact or disruption claims when the segregation of costs may be more difficult.

The total cost approach, although preferred by claimants because of the ease of computation, is generally discouraged by courts. This method assumes that the contractor was virtually fault-free. The total cost method is also fraught with uncertainties such as whether the contractor’s bid was reasonable, and the manner in which job costs are accounted. For these reasons, numerous court decisions have established fairly rigorous requirements for the presentation of total cost claims:

- Other methods of calculating damages are impossible or impractical.

- Recorded costs must be reasonable.

- The contractor’s bid or estimate must have been accurate (i.e., contained no underbidding).

- The actions of the plaintiff must not have caused any of the cost overruns.43

The second requirement, the reasonableness of recorded costs, is typically not a difficult assumption to prove. The claimant must demonstrate the appropriateness of costs, the reliability of the contractor’s accounting methods and systems, and a relationship to industry practices and standards. Ironically, the more detailed and well documented the claimant’s costs are, the more vulnerable the claimant is to an argument that it can use another method for calculating damages and, therefore, fails to satisfy the first requirement for use of the total cost method.

The last two requirements are the most difficult to meet. Proving the contractor’s bid was strictly accurate is challenging. That proof might require a comparison of other bids and supplier and subcontractor quotes to bid amounts as well as the comparison of material quantity estimates to contract drawings. Presenting such an analysis is expensive, often difficult to follow, and easily refutable because most bids rely on assumptions. Due to the nature of the bidding process, many of these assumptions are accumulated in the absence of accurate information.

Establishing the claimant was blameless for any overruns is perhaps the most difficult aspect of a total cost claim and why the method so rarely succeeds. The claimant essentially attempts to prove causation by showing the damages were not its own fault and therefore must be due to the acts of the other party. The premise is easily attacked by demonstrating only a single area of potential blame attributable to the contractor, which could erode the credibility of the entire total cost claim. That is why this method often has been defeated in practice and why parties may instead pursue a “modified” total cost method, as discussed in Section II.C of this chapter.

Owners probably view contractor total cost claims with even greater suspicion and distrust than do the courts, so much so that the credibility of the entire claim and the claimant can be undermined. The difficulties of establishing the prerequisites for use of a total cost calculation in court, combined with the skepticism it can generate, counsel against use of the total cost method whenever possible.

B. Segregated Cost Method

The segregated cost method of pricing claims is more difficult to use than the total cost method or the modified total cost method, but it is usually a more accurate, reliable, and persuasive way of presenting damages. Under this approach, the additional costs associated with the events or occurrences giving rise to the claim are segregated from those incurred in the normal course of performance of the contract. For example, on an extra work claim, the pricing would reflect an allocation (actual or estimated) for the additional labor, materials, and equipment used in performing the extra work. If the project was delayed, costs of added (or extended) field overhead and home office overhead would also be calculated.

The use of this cause-and-effect methodology most often yields an accurate, well-defined, and defensible presentation of damages. It may, however, be extremely difficult to accomplish in the absence of detailed and contemporaneous job cost record keeping and sophisticated cost-control systems that segregate changed or impacted work. This method tends to have added credibility when the person presenting the damage calculation shows the sum of all specifically identified damages does not equal the total difference between the bid cost and total cost (i.e., the total cost method). The difference remaining represents the costs related to contractor-caused events that have been excluded from the claim.

C. Modified Total Cost Method

Another general approach to calculating and presenting damages borrows from the concepts of both the specific identification (segregated costs) and total cost methods. The modified total cost method employs the inherent simplicity of the total cost approach but modifies the calculation to demonstrate more direct cause-and-effect relationships that exist between the costs and acts giving rise to liability. The success of the approach often depends on the extent of the modifications that demonstrate the cause-and-effect dynamics.

The initial step in calculating damages using the modified total cost method involves adjusting the contractor’s bid for any weaknesses uncovered during job performance, whether they were judgment or simple calculation errors. A reasonable bid (an as-adjusted bid) is thus established. The recorded project costs are then similarly examined for reasonableness, and reductions are made for costs that cannot be attributed to the owner, such as unanticipated labor material cost escalations that are not tied to the alleged basis for liability.

Focusing on specific areas of work can further refine the modified total cost calculation or cost categories related to the claim issues. For example, if the claim relates to a differing site condition that affected only site work and foundations and not the balance of the project, the claimant should focus only on those areas in the calculation and eliminate extraneous costs and issues that complicate and dilute the credibility of the pricing.

Although the modified total cost approach often is viewed as a method of avoiding the unfavorable scrutiny generally given to a total cost analysis, courts and boards of contract appeals may apply the same standards of admissibility to modified total cost claims as they have in the past to traditional total cost claims.44 If the claimant has modified the cost calculation properly and not relied on a simplistic approach, the modified total cost method is far more likely to withstand scrutiny and offer a credible means of quantifying a claim.

D. Quantum Meruit Claims

A final type of damage theory involves an analysis of the “reasonable value” of the work performed. Quantum meruit is an equitable doctrine meaning “as much as deserved.” This method of recovery typically measures damages under an implied contract theory and is based on the concept that no one should unfairly benefit from another’s labor or materials. In these circumstances, the law creates a promise to pay a reasonable amount for the services furnished, even without a specific contract. For instance, mechanic’s liens allow contractors and subcontractors to recover the reasonable value of their labor and materials used in improving property.

Quantum meruit generally is used in damage claims when the contractor does not have a written agreement to perform the work and the other party has been “unjustly enriched” by work performed.45 Quantum meruit also may be available if there has been a material breach of the contract and the contractor elects to rescind the contract and seek the reasonable value of the benefits.46 In most states, the contractor is not limited to the price specified in the initial agreement. The proper preparation and presentation of such a claim often can render proof of damages much easier, avoid the problems inherent in seeking a “total cost” recovery on a pure contract breach theory, and bring about recovery in excess of actual contract prices.47

III. Contractor Damages

The material in this section is not intended to provide an all-inclusive listing of categories of potential claims or cost elements. Instead, cost elements will vary depending on the circumstances of each case. The elements that follow are examples of the more common types of claim items in construction disputes. Many items of damages a contractor will suffer may fall into more than one of these categories.

A. Contract Changes and Extras

In most instances, a contractor presenting an affirmative claim to the owner will be seeking damages arising from changes in the anticipated quality, quantity, or method of work. Obviously, quality and quantity changes are relatively easy to discern. One clear, colorful, and effective way of describing such changes is to say that “The owner had the contractor build a Mercedes rather than the Ford required by the contract.”

The owner that requires a contractor to perform an additional quantity of work is susceptible to a claim if the contractor has kept accurate records of the amount of work performed and can prove the difference between actual performance and what a reasonable interpretation of the contract would require.48 The contractor seeking to recover additional costs associated with changes in the anticipated method or sequence of construction—a category that includes delay, disruption, and acceleration damages—faces potential problems. These damages are more difficult to understand and prove with reasonable certainty. In addition, the contractor’s records may furnish little support for the total claimed impact of a change in the anticipated method or sequence of work.

In recognition of the frequency of disagreements over pricing, contracts frequently include terms dictating the methodology for determining the price of extra or changed work. For example, the AIA A201 (2007 ed.) provides several methods of determining costs for changes, including: (1) mutual acceptance of a substantiated lump-sum price, (2) contract or subsequently agreed-on unit prices, (3) cost plus a mutually acceptable percentage or fixed fee, or (4) a method determined by the architect when the contractor fails to respond promptly or disagrees with the chosen method for adjustment in the contract sum.49 When a method determined by the architect is employed, the contractor must present an itemized accounting with supporting data, and generally is limited to recovery of the costs of labor, materials, supplies, equipment, rentals, bond and insurance premiums, permit fees, taxes, direct supervision, and other related cost items.50

Paragraph 8.3, “Determination of Cost,” in ConsensusDocs 200 (© 2011, Revised 2014), contains the following provisions regarding the pricing of a change in the work:

8.3 DETERMINATION OF COST

- 8.3.1 An increase or decrease in the Contract Price or the Contract Time resulting from a change in the Work shall be determined by one or more of the following methods:

- 8.3.1.1 unit prices set forth in this Agreement or as subsequently agreed;

- 8.3.1.2 a mutually accepted, itemized lump sum;

- 8.3.1.3 COST OF THE WORK Cost of the Work as defined by this subsection plus _____% for Overhead and _____% for profit. “Cost of the Work” shall include the following costs reasonably incurred to perform a change in the Work:

- * * *

- 8.3.1.4 if an increase or decrease in the Contract Price or Contract Time cannot be agreed to as set forth in subsection 8.3.1, and the Owner issues an Interim Directed Change, the cost of the change in the Work shall be determined by the reasonable actual expense incurred and savings realized in the performance of the Work resulting from the change. If there is a net increase in the Contract Price, the Constructor’s Overhead and profit shall be adjusted accordingly. In case of a net decrease in the Contract Price, the Constructor’s Overhead and profit shall not be adjusted unless ten percent (10%) or more of the Project is deleted. The Constructor shall maintain a documented, itemized accounting evidencing the expenses and savings.

- 8.3.1.1 unit prices set forth in this Agreement or as subsequently agreed;

- If unit prices are set forth in the Contract Documents or are subsequently agreed to by the Parties, but the character or quality of such unit items as originally contemplated is so different in a proposed Change Order that the original unit prices will cause substantial inequity to the Owner or the Constructor, such unit prices shall be equitably adjusted.

- * * *

Based either on common sense or a contract clause, the reasonableness of any claimed cost will be a critical factor in any pricing dispute. In federal government construction contracting, the controlling guidance on what is a reasonable cost is provided by the following provision of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR):

FAR § 31.201–3 Determining Reasonableness

- A cost is reasonable if, in its nature and amount, it does not exceed that which would be incurred by a prudent person in the conduct of competitive business. Reasonableness of specific costs must be examined with particular care in connection with the firms or their separate divisions that may not be subject to effective competitive restraints. No presumption of reasonableness shall be attached to the incurrence of costs by a contractor. If an initial review of the facts results in a challenge of a specific cost by the contracting officer or the contracting officer’s representative, the burden of proof shall be upon the contractor to establish that such cost is reasonable.

- What is reasonable depends upon a variety of considerations and circumstances, including

- Whether it is the type of cost generally recognized as ordinary and necessary for the conduct of the contractor’s business or the contract performance;

- Generally accepted sound business practices, arm’s length bargaining, and Federal and State laws and regulations;

- The contractor’s responsibilities to the Government, other customers, the owners of the business, employees, and the public at large; and

- Any significant deviations from the contractor’s established practices.51

- Whether it is the type of cost generally recognized as ordinary and necessary for the conduct of the contractor’s business or the contract performance;

If the contract dictates a method for pricing extra or changed work, such as the private industry form contract terms just quoted, the contractor should understand this methodology and implement it with respect to the construction project accounting system being utilized. If the contract does not provide a formula or basis for pricing such work, the prudent contractor should still implement accounting methods that contemporaneously account for these added costs.

B. Wrongful Termination or Abandonment

A contractor may be damaged if there is a breach of contract by the owner that prevents the contractor from performing the contract. In such a situation, the contractor is entitled to be placed in as good a position as it would have been in had the contract been performed. This generally means the contractor can seek lost profits so long as they can be proven with reasonable certainty.52 This rule also applies to subcontractors that may be prevented from performing, as in the case of wrongful termination of the subcontract by the general contractor.53

Once the contractor begins performance, it may find the owner (or, if it is a subcontractor, the general contractor) has committed a material breach of some obligation, either express or implied. In these circumstances, and if the breach is a major one, the contractor could treat the breach as terminating its contract, suspend construction activities, and seek to recover damages.

If such an election were made, the contractor could pursue a number of means of establishing damages. First, it might seek to recover out-of-pocket expenses, less the value of any materials on hand, plus lost profits.54 Alternatively, the contractor might seek recovery based on the total contract price, less the total cost of performing the contract, plus any expenses incurred in performing until the material breach.

In addition, if there is some reasonable basis for pursuing this method, the contractor might seek the contract price of work performed through the time of material breach, plus a profit on all unperformed work.55 Obviously the election made by the contractor will depend on the applicable rule of damages in the particular jurisdiction, the extent of the contractor’s records, whether the contractor would have made a profit, and provisions of the construction contract, which may limit the remedies available.

More typically, however, the contractor will continue to perform after the “breach” by the owner (or the general contractor) and will seek to recover damages after completion of the contract.56

C. Owner-Caused Delay and Disruption

In the “typical” delay-disruption case, one of the contractor’s tasks is to establish and isolate the period of delay caused by the adverse party. Once this is done, proof of damages involves itemizing those fixed (ongoing) costs incurred during that period of delay. If, however, the period of delay itself cannot be isolated in this manner, the ensuing problems can be difficult. For example, courts generally will not make any effort to apportion damages in a situation where both parties are found to have contributed to the delays in completion of the contract.57 In those courts, where each party proximately contributes to the delay, “the law does not provide for the recovery or apportionment of damages occasioned thereby to either party.”58 Some courts, however, depart from this general rule and allow each party to recover for delays caused by the other.59

One indirect cost attributable to a delay is extended overhead costs incurred by the contractor. Overhead “refers to indirect costs that a contractor must expend for the benefit of the business as a whole, as opposed to direct costs, which are costs specifically identified with a final cost object such as a contract.”60 There are two specific types of overhead costs that are allocated to every project that a construction contractor performs.

1. Field Office Overhead

The first type of overhead is known as field office overhead, which is also commonly referred to as extended general conditions.61 Extended field office overhead consists of “[c]osts incurred at the job site incident to performing the work, such as the cost of superintendence, timekeeping and clerical work, engineering, utility costs, supplies, material handling, restoration and cleanup, etc.”62 Unlike home office overhead, this category of overhead is attributable to a particular contract or project.

A contractor generally is entitled to recover field overhead costs on changes that extend the time of contract performance. These changes include both change orders that add to the scope of the contractor’s work as well as changes or events that impact contract performance and that cause a compensable delay on the project. Such costs are attributable to the increase in costs for continuing to run and staff a project for a time period not contemplated at the time of contracting.63 As with any other type of delay or disruption damage, these costs are recoverable “in order to make the contractor whole.”64

A contractor may allocate these costs as direct costs or indirect costs, depending on the contractor’s generally used accounting method. For example, if project supervision and administration are stated as direct costs, then “an equitable adjustment for extended field supervision and administration is calculated as a direct cost item.”65 If field overhead is charged to a general expense pool as an indirect cost, it should not be part of any direct cost claim; instead, it should be listed as a separate item in any equitable adjustment request.66 One recognized means of calculating direct costs for extended field overhead is “to compute a daily rate by dividing total labor supervision and administration costs on the project by the total days of contract performance and then multiplying the result by the number of days of compensable delay.”67 This same accounting method also may be used during the project by dividing expected field overhead costs by expected total days of contract performance to obtain the per-day rate, then multiplying that number by the number of days performance is extended.

As with other claims, it is necessary that a contractor show first that it is entitled to damages for delay. Once this is done, the contractor can recover costs for field overhead, even those not included in the original bid. An illustrative case on this comes from the District of Columbia Contract Appeals Board in MCI Constructors.68 In MCI, a default termination was converted to a termination for convenience by a prior board decision. The board determined MCI’s proper amount of resulting compensation, including a claim for extended field overhead costs. The District of Columbia argued that MCI significantly underbid its supervisory costs, failing to include bid items for project engineering, clerical work, main office engineering, and main office expediting—items MCI had intended for the project manager and superintendent to handle at the project outset.

In awarding recovery for all these items as field overhead costs, the board stated that it could find “no reason to deny MCI a pro rata share of such costs actually incurred during a compensable delay period…[e]ven though MCI commenced charging directly to the job some supervision and administrative costs it had not bid.”69 Such a decision was reached despite the alleged underbidding, because the board was not giving “MCI any undue recovery[,] because this computation applies only to the delay period and covers labor supervision and administration that MCI would not have incurred but for the District’s constructive changes.”70 Due to the inability to identify what portion of the amount the equation provided had already been recovered through change orders signed during the project and what portion had been allocated to a claim item for pending change orders, the board then awarded an amount based in part on a “jury verdict” finding.71

The lesson of MCI Constructors is apparent: Even if a contractor incurs field overhead costs that were not bid originally, it is important to segregate all these costs and apply them to change orders and delay claims. To add additional specificity to the claim, further record keeping should identify the costs allocated to each change order item.

2. Home Office Overhead

The second type of overhead cost is referred to as home office overhead costs, which include such expenditures as administrative staff salaries, accounting and payroll services, general insurance, office supplies, telephone charges, depreciation, taxes, and utility costs. These costs are “expended for the benefit of the whole business, which by their nature cannot be attributed to any particular contract.”72

Contractors typically rely on project revenue to support their home office operations, and, accordingly, contractors include a markup in their bids for new work to absorb such costs. Allocated over the project’s planned duration, this markup provides monthly revenue that is used to pay (or absorb) rent, home office staff salaries, accounting and payroll services, general insurance, office supplies, telephone charges, depreciation, taxes, and utility costs. If the project time is extended without increasing the amount of the markup, the dollars available to absorb monthly overhead are reduced.

Several recent decisions by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit appear to make it more difficult for a federal government contractor to recover unabsorbed home office overhead using the Eichleay formula for government-caused delays.73

a. The Original Eichleay Decision

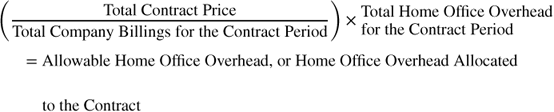

The Eichleay formula originated with Eichleay Corp., an ASBCA decision, in which the board specifically approved the contractor’s three-step formula for determining the amount of recoverable home office overhead.74 Since the original decision, this formula has become the mandatory method for calculating claims for unabsorbed home office overhead on federal government construction contracts.75 The three steps are:

- Determine the overhead allocable to the contract by multiplying the total overhead by a ratio of the contract’s billings to the total billings of the contractor for the contract period.

- Calculate a daily overhead rate for the contract by dividing the overhead allocable to the contract by the number of days of contract performance.

- Determine the total overhead recoverable by multiplying the daily overhead rate for the contract by the number of days of delay.

This formula may be schematically summarized as: