Protection of Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights: Addressing Violence Against Women

Protection of Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights: Addressing Violence Against Women

Introduction

Violence against women is one of the most widespread human rights violations as well as a public health problem in need of urgent attention. It is sometimes called gender-based violence as it is both maintained by, and in turn perpetuates, gender inequality that puts women and girls in subordinate positions. This violence has many devastating consequences for women’s lives and their health, including their sexual and reproductive health, and their human rights.

Violence against women can take many forms: physical, sexual, and emotional. It can take place in the home, the community, and state institutions, and be perpetrated by intimate male partners, acquaintances, or strangers. In certain settings, such as those in conflict or involving displacement or in prisons, women may be at increased risk, particularly of sexual violence by both State and non-State actors.

Most of the data on the impact of violence on health comes from studies of either intimate partner violence or sexual violence. While recognizing that other forms of violence are important also, this chapter predominantly addresses these two forms. It provides an overview of the prevalence of this violence, its impact on women’s sexual and reproductive health, and on their human rights. It considers the implications of this for health care provision and makes some recommendations for action.

Violence Against Women: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Health Consequences

The World Health Organization defines violence as: “The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual … that results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.” The inclusion of the word “power” broadens “the conventional understanding of violence to include those acts that result from a power relationship, including threats and intimidation.”1

Intimate male partners are most often the main perpetrators of violence against women, a form of violence known as intimate partner violence, “domestic” violence or “spousal (or wife) abuse.” Intimate partner violence and sexual violence, whether by partners, acquaintances or strangers, are common worldwide and disproportionately affect women, although are not exclusive to them. Other forms of violence such as trafficking also affect women and children more often. In situations of conflict, sexual violence against civilians, including men, is increasingly being documented.

Globally, studies have shown that:

- between 10% and 69% of women report that an intimate partner has physically abused them at least once in their lifetime;2, 3

- between 6% and 59% of women report attempted or completed forced sex by an intimate partner in their lifetime;2

- between 1% and 28% of women report they have been physically abused during pregnancy by an intimate partner;2, 4

- between 7% and 48% of adolescent girls and between 0.2% and 32% of adolescent boys report that their first experience of sexual intercourse was forced;1

- approximately 20% of women and 5%– 10% of men report having been sexually abused as children;5

- between 0.3% and 12% of women report sexual violence by a non-partner,2

- it is estimated that 2.5 million people are trafficked every year,6 the majority of them women and children.

Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence (and Sexual Violence)

Violence against women is a complex phenomenon driven by factors at the level of the individual woman, the perpetrator, the relationship and family, the community, and the society. Research has identified the following as common “risk factors” for intimate partner violence:7 being young; witnessing or suffering family violence as a child; suffering sexual abuse as a child; alcohol and substance abuse; relationships characterized by inequality and power imbalance; poverty, economic stress, and unemployment; gender inequality; lack of institutional support or sanctions; and social norms that support traditional gender norms, condone violence, or promote models of masculinity based on abuse of power and aggressiveness.

The majority of research on risk and protective factors has until recently been conducted in high-income countries and therefore needs to be tested for its relevance to middle- and low-income countries. Some factors may operate differently in different contexts, as has been shown for example with women’s education levels and status disparities within couples.8 In high-income settings women’s education is usually protective, whereas in low-income settings it may be a risk factor, particularly when it is the exception and there are disparities of education status within the couple.

Health Consequences

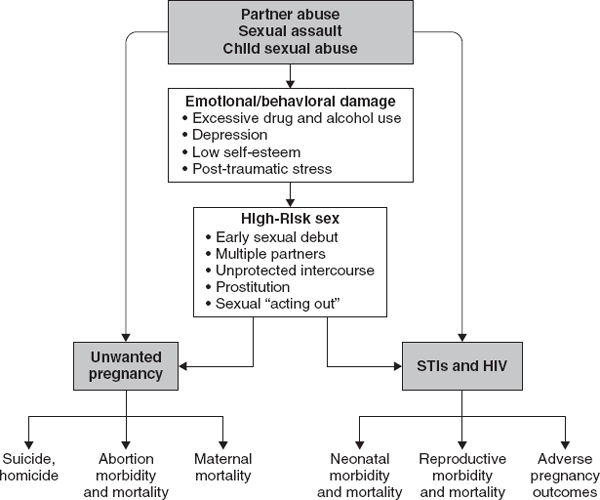

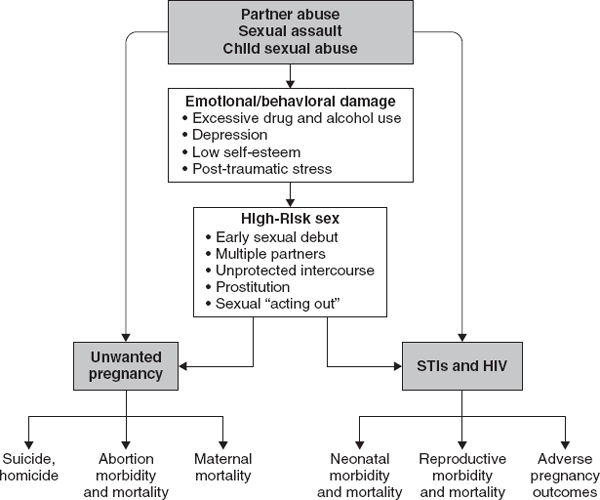

Violence is associated with a wide range of negative health outcomes for women. These range from mild to severe injuries including fractures and permanent damage to ears and eyes,9 chronic pain syndromes including chronic pelvic pain,10 depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders and many other mental health problems,11 and sexual and reproductive health problems. Whether directly increasing the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS, and unwanted or mis-timed pregnancies through rape and sexual assault, or indirectly through inability to request or negotiate the use of condoms because of actual violence, coercion/intimidation or fear of violence (Figure 29.1), violence contributes to women’s increased risk of unwanted pregnancies—which may lead to unsafe abortion and gynecological problems.12 This association has been documented in many countries.13

Figure 29.1 Violence against women: Direct and indirect pathways to unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Source: Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending Violence Against Women. Population Reports, Series L. No. 11. Baltimore: Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health (JHUSPH); Takoma Park: Center for Health and Gender Equity (CHANGE). Vol. XXVII, No. 4, December; 1999.

Intimate partner violence during pregnancy is not uncommon. In the WHO multi-country study between 1% and 28% of women reported being physically abused by a partner in at least one of their pregnancies, with between 4% and 12% reporting this in the majority of the sites.2 This frequently involved blows or kicks to the abdomen. This is consistent with findings in other studies where the range in low-income countries was between 4% and 32%.4 It must be noted however that the studies in this review use different measures of violence and some also include sexual and emotional violence. There is clearly some cultural variation in the level of protection to violence that pregnancy may confer to women and in most places violence appears to reduce during pregnancy, but there is a group of women for whom the pregnancy may be what triggers the violence or for whom the violence gets worse during pregnancy.14

Violence during pregnancy has been found to be associated with pre-term labor,15 miscarriage, stillbirth,16 abortion,17 low birth weight,18 lower levels of breastfeeding,19 and higher rates of smoking and drinking during pregnancy.20 Recent studies also document an association of intimate partner violence with infant and child mortality.21

Half to two-thirds of femicide or the murder of women is perpetrated by an intimate partner.22