Positive Rights and Proportionality Analysis

5

Positive Rights and Proportionality Analysis

I. Introduction

Positive rights, granting a right to positive action by state authorities, have a growing importance in the jurisdiction of many constitutional and international courts worldwide. In the guise of socio-economic rights, they have attracted special attention in the recent decade.1 Properly understood, however, positive obligations may not only occur with special socio-economic rights, but with any human right. Thus, the division of rights to ‘civil’ versus ‘social’ rights is to be questioned—at least it is not to be mixed up with the division of ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ rights.2 This invites special attention to the understanding and theoretical analysis of positive rights, in particular as far as the proper standard of judicial review is concerned. Generally speaking, the greater part of our theoretical frameworks is devoted to the understanding of negative aspect of rights only, while at the same time there is growing evidence that adjudication of socio-economic rights must move beyond the classic liberal constitutional model.3 Hence, it is high time to engage in a more thorough study of the particularities that positive rights may bring about, both in theoretical analysis and constitutional court’s jurisdictional practice.

This chapter analyses the relation between positive rights and proportionality with the help of Alexy’s principles theory. Applying the proportionality test to both negative and positive rights may undermine any margin of appreciation of the state authorities. This gives rise to the problem of over-determination. An account of different types of the margin, however, helps to understand the precise scope of the margin in the field of positive rights. The Hatton case is used as a seminal example to illustrate these issues.

It is widely acknowledged that human rights do not only provide protection for individual freedom against an intrusive state, but may also require the state to take positive action.4 The ECtHR has increasingly recognized implied positive rights of Member States as arising from the rights in the ECHR. Positive rights have a ‘growing importance’ in the jurisprudence of the ECtHR.5 There is increasing evidence that literally all human rights involve both negative and positive duties.6 Hence, the request to elaborate the duties embodied in human rights comes as no surprise:

Identifying the multiple duties that may be relevant to any one right sharpens an understanding of what is distinctive to and necessary to realize that right.7

Nonetheless, Mowbray’s account that ‘the issue of positive obligations under the ECHR has been subject to limited commentary in the existing literature’8 is still valid today.

A central topic in the current debate on human rights is the role of weighing as a means of achieving the specific balance between negative and positive rights. Balancing plays a central role in the jurisdiction of the ECtHR. In order to analyse the relation between balancing and positive rights further, we will follow Alexy’s account of discursive constitutionalism9 here by applying his most recent analysis10 on the structure of positive rights to the case law of the ECtHR. In particular, we will address the proportionality test in the context of negative rights first, so that the differences in the context of positive rights become as clear as possible. Finally, we will take up the issue of the margin of appreciation as related to positive rights.

Prior to this, we will identify the structure of positive rights as the main focus, highlight the logical basis of the argument developed here, and introduce the Hatton case, which will be used as an example throughout this chapter.

1. Justification, content, and structure

Positive rights cause several problems, which may be classified in three groups.11 The first group concerns the justification of positive rights. It comprises questions such as whether and to what extent positive rights should be included in a catalogue of rights and how their incorporation, notwithstanding whether it is achieved by means of express textual requirement or by means of judicial creation, can be rationally justified.12 In this group belongs the question of whether and to what extent positive functions of the state are a question of rights, rather than politics or morals.13 It has been shown by Mowbray that a common justification for the judicial recognition of positive rights under the ECHR has been to ensure that the rights are ‘practical and effective’.14 The second group of problems deals with the content of positive rights. It is crucial to ascertain the precise scope of positive rights. Here, the financial consequences of introducing positive rights play a role, as well as the question how positive rights are related to the fundamental conflict between freedom and security. Both the justification problem and the content problem can only be sufficiently addressed if the structure of positive rights is clear. This is the third group of problems, and it will be the focus of the present chapter.

From a practical perspective, the structure of positive rights is the most eminent problem for the Court in applying convention norms imposing positive rights. Furthermore, two most fundamental issues are intrinsically connected to the problem of the structure of positive rights, namely the applicability of the proportionality test to positive rights and the function of the margin of appreciation doctrine.

2. Disjunctive structure

The ECtHR has remarked frequently that it does not really matter whether it analyses a case in terms of a positive or a negative right, since in both cases a fair balance between the competing interests has to be struck:

Whether the case is analysed in terms of a positive duty on the State to take reasonable and appropriate measures to secure the applicants’ rights … or in terms of an interference by a public authority …, the applicable principles are broadly similar. In both contexts regard must be had to the fair balance that has to be struck between the competing interests of the individual and of the community as a whole.15

Accordingly, the Court sometimes even leaves open whether a positive or a negative right is at stake:

The Court is not therefore required to decide whether the present case falls into the one category or the other.16

These statements by the Court are correct only in so far as the principle of proportionality, requiring a fair balance, is, indeed, applicable to both categories. However, apart from this general level, the position of the Court is mistaken. The application of the proportionality test in detail is fundamentally different in both categories, as will be shown below. This is due to the important fact that the internal structure of positive rights is fundamentally different from those of negative rights in at least one respect.17 Negative rights forbid to destroy, obstruct, or interfere with a legal interest. If it is forbidden to destroy or interfere with a legal interest, then any action, which amounts to or causes destruction or interference, is forbidden. On the contrary, if there is a right to protect or rescue a legal interest, not any action that amounts to or causes protection or rescue is obligated. The prohibition of killing people, for example, implies the prohibition of any killing action, whereas the right to rescue people does not demand any rescue action. Rather, in the latter case, if it is obligated to rescue someone from drowning, there is a free choice as to the means, as long as the result of rescue is achieved: one may rescue by swimming towards him, or by throwing a life-saver, or by pulling him aboard a boat. The right is not to all three actions of rescue, but only to one of the three. Therefore, positive rights have an alternative or disjunctive structure, whereas negative rights have a conjunctive structure. The alternative structure of positive rights implies that the unlawful omission of an action has no definite opposite.18 Rather, there are as many opposites as possible alternatives. Positive unlawful actions of the state, on the contrary, have a definite opposite, namely the omission of the same unlawful action.

All important differences between positive and negative rights follow from this fundamental difference. The Court can under no circumstances leave open the question of whether it analyses the case in terms of a positive or negative right. And it has to follow a different structure of the proportionality test in order to determine whether a fair balance has been struck between the competing interests.

3. The Hatton case

We will use the Grand Chamber judgment in the Hatton case as an example throughout this chapter. Hatton originated in an application against the United Kingdom lodged by eight UK nationals in 1997. They lived, or had lived, near Heathrow Airport and were complaining about the noise levels caused by night flights at the airport. Before 1993, the noise caused by night flights had been controlled through restriction on the total number of take-offs and landings. After that date, however, noise was regulated through a system of noise quotas. Each aircraft type was assigned a ‘quota count (QC)’. The noisier the aircraft, the higher the QC. This allowed aircraft operators to select a greater number of quieter aircraft or fewer noisier ones, provided the QC was not exceeded. The new scheme imposed these controls strictly between 11.30 pm and 6 am. The introduction of the 1993 scheme was preceded by a number of studies on the effects of aircraft noise on sleep disturbance, on the one hand, and on the economic effect of night-time restrictions of flights, on the other.

The 1993 scheme led to a considerable increase in the number of movements at night. Following the introduction of the 1993 scheme, local authorities in the area sought judicial review. The scheme was found to be contrary to a statutory provision which required that a precise number of aircraft be specified, as opposed to a noise quota. This caused the government to include a limit on the number of aircraft movements allowed at night. In addition to the restrictions on night flights, a number of noise mitigation and abatement measures were in place at Heathrow.

The case was brought to the ECtHR in May 1997. The applicants alleged that the government’s policy on night flights at the airport gave rise to a violation of their rights under Article 8 of the Convention, the right to respect for private and family life. In 2001, a Chamber judgment was delivered which held (by 5 votes to 2) that there had been a violation of Article 8, and (by 6 to 1) that there had also been a violation of Article 13. The British government requested that the case be referred to the Grand Chamber, which delivered its judgment in July 2003. The Grand Chamber (by 12 votes to 5) held there was no violation of Article 8 and (by 16 votes to one) there was a violation of Article 13.

The complaint principally focused on a substantive breach of Article 8, namely sleep deprivation. But in addition, it focused on the procedural unfairness of the lack of proper scrutiny of the government’s policy in respect of night flights and noise quotas at Heathrow. Lastly, as far as Article 13 (right to an effective remedy) is concerned, it focused on the absence of a fair trial to remedy the nuisance. In order to assess the structure of positive rights, we will address the substantive claim as to Article 8 here only.

II. Negative rights and the proportionality test

In order to illuminate the differences in the internal structure of the proportionality test as clearly as possible, we will first analyse the Hatton case from the perspective of a negative right. In fact, there is a collision between a negative and a positive right in this case: the positive right of the state to protect its citizens from the exposure to noise stemming from night flights collides with the negative right not to hinder the economic activities of the aircraft operators by imposing too strict controls on night flights. The former right follows, prima facie, from Article 8 ECHR, whereas the latter right stems, prima facie, from Article 1 Prot. 1.

The negative right has not, as an individual right, been extensively considered by the Court. Rather, the Court considered the economic interests mainly from the perspective of the general public, as opposed to individual interests of the aircraft operators.19 In order to get a full picture of the case it is decisive to reconstruct the collision of all relevant principles and, hence, to take into account negative individual rights also. In the Hatton case, this aspect has been stressed, for example, by Sir Brian Kerr, who dissented in the Chamber judgment. He called for having regard for ‘the rights and freedoms of air carriers’ as the colliding principle rather than mere ‘macro-economic policy’.20

As far as the negative right is concerned, it does not make any difference whether one addresses the economic interests as individual rights or as interests of the general public, as long as both have convention status under Article 8 § 2.

Whenever a negative and a positive right collide with each other, it is possible to address the case from both perspectives. One may ask whether the negative or the positive right have been violated, respectively. In this section, we will take up the question as to the violation of the negative right; in the next section, we will take up the questions as to the violation of the positive right.

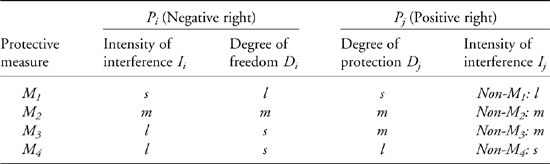

We will first consider the negative right not to interfere with the economic interests of the aircraft operators. This perspective from the negative right is much easier to analyse than the perspective from the positive right. Pi shall be used for the Article 1 Prot. 1 right, Pj shall be used for the Article 8 right. Pi is a negative right, requiring the state to abstain from interfering with the economic activities, including operating night flights, of the aircraft operators. Pj is a positive right, requiring the state to protect the people living in the area from sleep disturbance by active measures such as introducing restrictions on night flights. Thus, we face a collision between a negative and a positive right here.

We shall assume that the abstract weights of both principles, that is Wi and Wj, are equal and, thus, cancel each other out. Also, we shall assume that the reliabilities of both the normative and the empirical premises are equal and, thus, need not be considered further. The result of the balancing, then, turns on the intensities of interference. We can therefore apply the weight formula in a reduced form here:

Formula 10 Weight formula in its reduced form

We will first consider the view of the government. As far as Ii is concerned, the government and the respondents from the airline industry stressed the economic importance of night flights. Other European hub airports, they argued, had less severe restriction on night flights than those imposed at the three London airports. If restrictions on night flights were made more stringent, UK airlines would be placed at a significant competitive disadvantage. Furthermore, they provided information showing that a typical daily night flight would generate an annual profit of up to £15 million. The loss of this profit would impact severely on the ability of airlines to operate.21 Hence, from this perspective, the interference that would occur with Pi if more restrictions on night flights would be imposed is serious (s). This assessment was shared by the British Air Transport Association, who submitted that a reduction in night flights would cause major damage to British Airway’s business.22

The government did not only argue in favour of Pi. It also focused on demonstrating that the interference with Pj was less severe.23 It pointed to the fact that the house market in the areas was thriving and that the applicants had not claimed that they were unable to sell their houses and move. Furthermore, sleep studies showed that external noise levels below 80 dBA were very unlikely to cause any increase in the normal rate of disturbance of someone’s sleep; and that even with noise levels between 80 and 95 dBA the likelihood of an average person being awakened was about 1 in 75. It follows from these arguments, that according to the government the intensity of interference with Pj is, if at all, moderate (m).

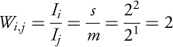

Under these conditions, from the government’s perspective, Wi,j is determined as in Formula 11:

Formula 11 Balancing from the government’s perspective

Thus, Pi takes precedence. The economic interests of the aircraft operators outweigh the interest of the people to be protected from noise disturbances.

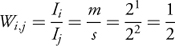

The picture changes, however, if we address the balancing from the applicant’s view. As far as Pj is concerned, they maintained that the disturbances caused by night flights were extensive because large numbers of people were affected and because the night noise was frequently in excess of international standards.24 Hence, the applicants argued for the intensity of interference Ij to be assessed as serious (s). As for Pi, they pointed to the fact that many of the world’s leading business centres (for example, Berlin, Zurich, Hamburg, and Tokyo) had full night-time passenger curfews of between seven and eight hours. Accordingly, the importance of Pj would be, if at all, moderate (m). Therefore, Pj takes precedence, as shown in Formula 12.

Formula 12 Balancing from the applicant’s perspective

The Grand Chamber explicitly recognizes that the relative weight, that is the value for Wi,j is decisive for the balancing outcome: