Overview of the US Legal System

- Checks and balances: Governmental power is divided between the national government and the states, and between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, to avoid any one group wielding excessive power.

- Enumerated powers: The federal government is a government of limited powers, having only those powers explicitly granted it by the Constitution.

- Law: There are various kinds of “law” that come from multiple sources.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an introduction to the American legal system, governmental structures, and sources of law. The concepts discussed here are fundamental to all American law; they are not unique to environmental law. But these fundamentals provide a context for understanding environmental law.

THE STRUCTURE OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT

The United States was created—or “constituted”—in 1789 by a document called the Constitution. The document was drafted by chosen representatives and then approved by the original thirteen states. At the time, this was a unique new phenomenon—a government created by, rather than imposed on, the governed. The people of America had very recently won their independence from England, and they were eager to protect their independence. Above all, they shied away from power concentrated in too few hands, which they saw as a recipe for tyranny.

The founders—the drafters of the Constitution—sought to establish a government strong enough to govern and defend the country while at the same time protecting the rights of the states and the people. They invented a system of government based on a new idea: separation and balance of powers. Power is divided among separate segments of government, as a check against abuse of power by any one segment. This idea, often called checks and balances, is a hallmark of American government.

SEPARATION OF POWERS: FEDERAL AND STATE

The Constitution created a unique federal system, consisting of a central—federal—government existing alongside sovereign individual states. The Constitution lists—or “enumerates”—specific powers allocated to the federal government, for example, the powers to declare war and print money. All other powers are reserved to the states and the people. Thus, the federal government is often called a government of enumerated powers or “limited powers.” The federal government exists in parallel to the state governments, now grown to fifty in number. Their structures and laws are largely similar, but not identical, to the federal government’s structure described below. This separation of powers between the federal government and the states—often referred to as a vertical separation of powers—is one of the checks and balances introduced by the Constitution to protect against tyranny (see table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Separation of Powers between National Government and States

| National Government | States |

| Enumerated Powers | Reserved Powers |

| Delegated by Constitution | Any Powers Not Delegated to National Government |

| Includes: | Includes: |

|

|

Note: The authority of national and state governments overlaps in many areas, including environmental protection.

In practice, the division between federal and state power is not quite as neat as in concept. The enumerated powers are explicit, but subject to interpretation. As a result, disputes are not infrequent as to whether a particular federal law crosses the line and encroaches on the powers reserved to the states. This is the theoretical question in debates over states’ rights. The ultimate arbiter is the US Supreme Court. Because the Court is a part of the federal government, you might think that states would always lose the dispute. But that is not so. At times in our history, the Court has interpreted enumerated powers broadly—stretching the language like elastic—but at other times it has interpreted federal powers narrowly, ruling in support of states’ rights.

Separation of Powers: Branches of Government

In addition to the vertical separation of powers between the federal and state governments, the Constitution created what is often called a horizontal separation of powers within the federal government. There are three fundamental powers or functions of government: legislative, executive, and judicial. Historically, in other nations, all of these powers were exercised by one sovereign individual or group. By contrast, the US Constitution divided these functions in the federal government among three separate and independent branches: Congress, the executive branch, and the judiciary (the courts). This horizontal separation of powers is another of the checks and balances introduced by the Constitution to protect against the risk of tyranny that comes with concentration of power in too few hands (see table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Branches of Government

| Legislative Branch | Executive Branch | Judicial Branch |

| Congress | President | Federal Courts |

| Consisting of: | Assisted by: | Consisting of: |

|

|

|

Note: This table is intended to emphasize that the branches of government are independent and equal. Although the table specifically depicts the federal branches, it could equally serve to illustrate the branches of a state government.

Legislative Branch

Legislation is the adoption of statutory law Laws enacted by Congress or a state legislature—what most people think of when they hear the word “law.” Congress is the federal branch vested with legislative power. It consists of two elected houses—the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Senate consists of two senators elected from each state. Thus, all states have equal weight in the Senate, regardless of population. By contrast, the number of representatives elected to the House from each state is proportionate to its population. America’s bicameral (two-house) legislature provides a layer of power-balancing. A bill (proposal) cannot become law unless approved by a majority of both houses.

Executive Branch

The federal executive branch consists of the president, vice president, and various departments and agencies. The head of each department (usually called the secretary) and the heads of some of the agencies (called administrators), along with a few other officials, comprise the president’s cabinet. The president and vice president are elected. The heads of departments and agencies are appointed by the president, but must be approved by the Senate (another example of balancing powers).

Judicial Branch

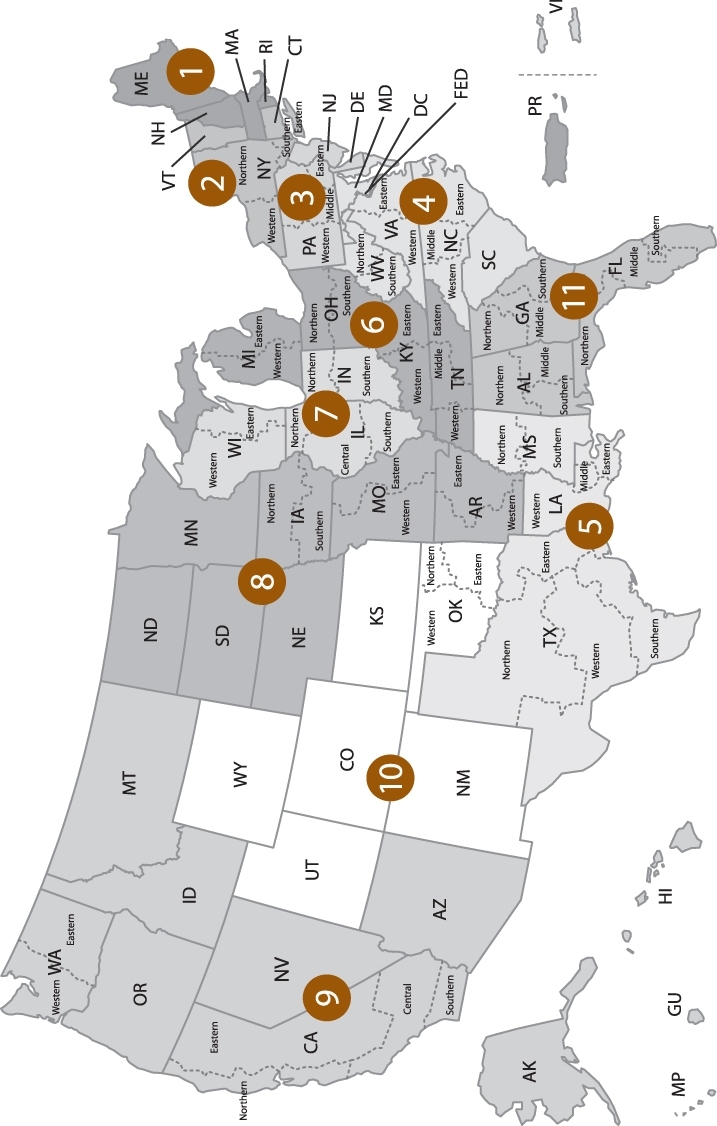

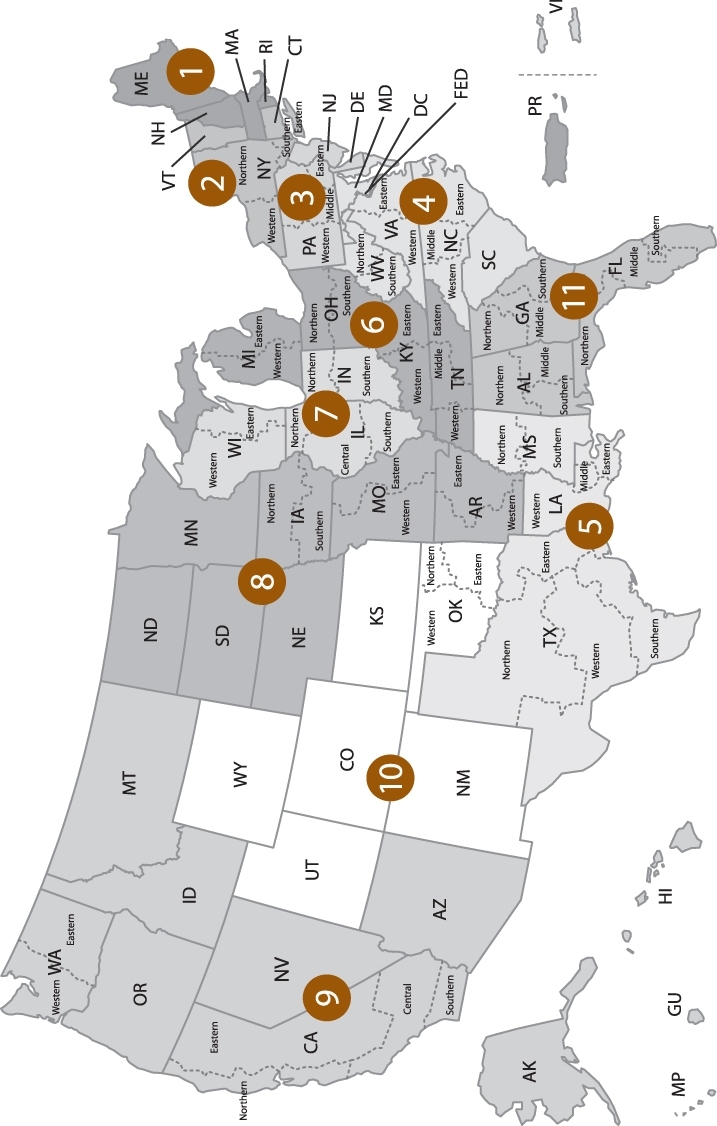

The federal judiciary forms a pyramid with three tiers. The large bottom tier is the trial court level, called the US District Courts. The term “District” here refers to state-based geographic areas, for example, the Western District of Pennsylvania. The narrower middle tier is the appellate level, called the US Courts of Appeal, often referred to as “Circuit Courts.” The term “circuit” refers to a geographic area covering several states (see figure 1.1). For example, the Third Circuit encompasses Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, so the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit presides over all the District Courts in those three states. The peak of the pyramid is the United States Supreme Court. A decision of an appellate court, such as the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, is binding only on the courts within its own circuit—that is, its own “jurisdiction.” But, if persuasive, its decision might be followed by courts in other circuits. Decisions of the Supreme Court are binding on all federal courts in all circuits. The Supreme Court agrees to hear relatively few cases each year. One major reason the Supreme Court might agree to accept an appeal is if there is a conflict among the decisions of two or more Circuit Courts of Appeal.

Figure 1.1 Geographic Boundaries of United States Courts of Appeal and United States District Courts

Source: www.uscourts.gov/court_locator.aspx

Federal judges are not elected. When there is a vacancy on a court, a new judge is appointed by the president, subject to confirmation by the Senate. The requirement of Senate approval, as with executive department heads, is another example of that hallmark American concept, the separation and balance of powers. The concept is carried even further with the federal judiciary. New executive department heads are appointed by each new president, and they can be removed by the president. By contrast, federal judges are appointed for life. They may not be involuntarily removed from office unless impeached by Congress. The reason is to protect the independence of the judiciary from the political branches—the legislature and executive. Courts often have to decide cases whose outcome could be adverse to the wishes of those other branches. Judges could not be expected to rule impartially if they risked being fired every time their decisions displeased the other branches.

State Governments

States do not derive their power from the federal government; each state is a sovereign government. Yet each state government is very similar in structure to the federal government. This structure is not imposed on the states by federal law. Rather, everybody does it because it works. Each state has its own constitution establishing the branches of government and how they are constituted and selected.

State legislatures almost all have two houses, just like Congress. (The sole exception is Louisiana, which has just one house.) Each state’s constitution provides how many legislators serve in each house and how they are chosen. The names vary; for example, a state might call its legislative houses the Senate and Assembly.

The governor of each state is its chief executive officer, corresponding to the office of president in the federal government. There may also be an officer called lieutenant governor, or something similar, corresponding to the vice president. Each state has executive entities called departments or agencies or commissions that do the daily work of government, similar to the departments and agencies at the federal level. Typically, a state has a Department of Environmental Protection—or similarly named entity—corresponding to the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

States commonly have a three-tiered judicial structure—trial courts, intermediate appellate courts, and a supreme court—just like the federal judiciary. States vary considerably, however, in the methods of selecting judges—for example, whether they are appointed or elected, and how that is accomplished. The term of office served by judges also varies from state to state.

Local Governments

Local governments are not sovereign; they are created by and derive their authority from the state. They have varying degrees of authority and autonomy, delegated by the state. Local governments come in various shapes and sizes, and they have various names—for example city, county, borough, and township. Local governments often play an important role in environmental protection—through zoning, planning, issuance of permits, enforcement, and in many other ways.

Who Takes Care of Health and the Environment?

Attention in this book will focus mainly on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA is responsible for administering most federal environmental legislation, and its sole mission is environmental. But other executive entities also play an important role in environmental protection, and many programs involve the work of multiple agencies in cooperation. For example, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) mission includes extensive environmental aspects, such as current energy production issues and dealing with the contamination of former atomic bomb production sites. The DOE and the EPA both are designated to participate in a Nuclear Response Team under the leadership of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), in case of a nuclear or radiological incident. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), an agency within the Department of Homeland Security, plays a leadership role in disaster planning and response, often working closely with the EPA. Later chapters of this book discuss the roles of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Food and Drug Administration in environmental health protection. The Department of Justice provides legal counsel to the EPA (and other agencies), as well as representing it in litigation.

In addition to EPA, FDA, and OSHA, other federal, state, and local agencies have statutory roles in responding to human health threats related to the environment, to food safety, and to the workplace. Sorting this out can be bewildering in any given instance, but recognizing the roles of these public health agencies is essential to understanding the response. A number of federal organizations focusing specifically on environmental health issues are part of the Department of Health and Human Services. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) is part of the National Institutes of Health. NIEHS funds research on environmental health issues; is the lead federal agency for the National Toxicology Program; publishes the leading journal in the field, Environmental Health Perspectives; and, under CERCLA, runs Superfund research centers and hazardous waste worker programs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the US Public Health Service includes the Center for Environmental Health (CEH). CEH is the primary federal response agency for environmental public health issues, working closely with the EPA. CEH also performs public health surveillance related to environmental issues, including a long-term survey of blood levels of over a hundred environmental agents. Another CDC component, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), overlaps organizationally with CEH. As described in the chapter on CERCLA, ATSDR provides the health component to the Superfund program. It is also the source of easily read as well as comprehensive “toxicological profiles” which are excellent sources of information about individual chemicals.1