Organizational Routines

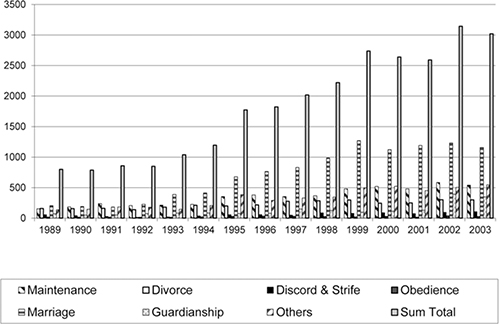

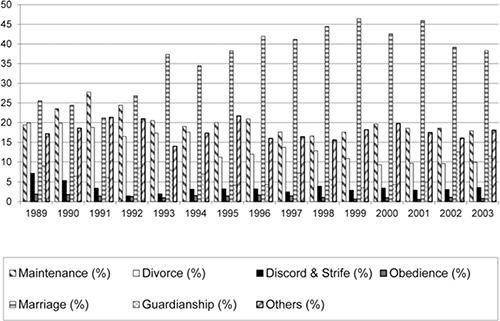

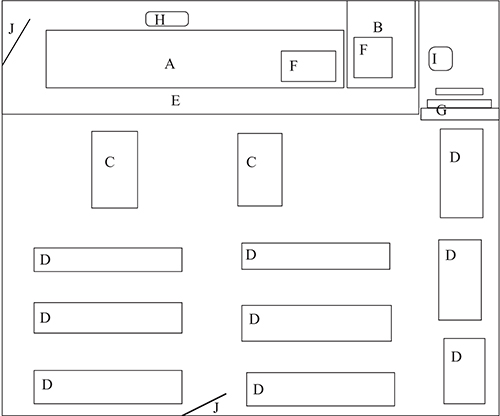

Chapter 7 Working days in the shari‘a court of West Jerusalem begin early and end late. Abu Zayd, the acting chief clerk, usually arrives at court before 06:30,1 and begins to prepare the court for the day. He takes out office accessories (e.g. court stamps, which are held in locked drawers), and piles up the dossiers for the day on the qadi’s desk. Between 07:00 and 07:30 the qadi arrives from Jaffa by car (a fifty minutes ride).2 By arriving so early to court, he told me once, he manages both to avoid the traffic jams at the entrance to Jerusalem, and to prepare himself for the day’s hearings (by going over the files). By 08:00 the rest of the staff, including the Jewish armed guard, arrive at the court.3 Litigants and their companions are beginning to gather before the guard as early as 08:00. The court door is opened to the public at 08:30 sharp, and the crowd immediately pours in, approaching the court staff (primarily Abu Zayd and his aide, Abu ‘Uday) with various questions and requests. Court hearings begin at 09:00 and end at 14:30, yet the timetable is very flexible and liable to constant changes. Thus I have often witnessed hearings that took place much later than 14:30. For example, on April 5, 1998, a hearing took place as late as 18:00 (Qadi Ziad ‘Asliyya); and conversely, on July 8, 2002, a hearing took place as early as 07:45 (Qadi Muhammad Zibdi).4 Usually, the first hearings of the day are dedicated to cases that do not involve litigation (mu‘amalat, hujaj)—mostly recognition of registered deeds such as marriage and divorce certificates.5 As mentioned above, many couples in Jerusalem register their marriages with a Jordanian ma’adhun rather than with an Israeli one. As a result, they later need to turn to the Israeli shari‘a court and ask for the recognition of their marriage, so that other Israeli authorities will recognize it as well. Since these cases constitute mere procedural acts, which do not rob much of the court’s time, the qadi tends to “clear the table” and to finish dealing with them in the morning. Later in the day, every time the court returns from its routine breaks, the first minutes are also dedicated to mu‘amalat. Figure 7.1 Types of Files in the Shari‘a Court in West Jerusalem by Year Source: based on data from The Shari’a Courts Administration Yet, while the judicial burden on the court in these cases is perhaps negligible, the administrative burden due to the processing of such a file is not negligible at all. Since in recent years the registration of deeds has come to constitute more than 50 percent of the total number of the court files (see Figures 7.1 and 7.2), it may be argued that the court’s “notary function” has become more dominant in its operation, whereas its “judicial function” has decreased. In this respect, the Israeli shari‘a court in West Jerusalem may be seen to resemble the shari‘a courts of “classical” and medieval periods, that were presumably notary institutions to a great extent (see Tyan 1959: 78–9, Wakin 1972: 9–10). Figure 7.2 Types of Files in the Shari‘a Court in West Jerusalem by Year (Percentage) Source: based on data from The Shari’a Courts Administration The judicial element in court practices is manifested in substantive suits (da‘wa, pl da‘wi). Typical suits deal with matrimonial issues that fall under the jurisdiction of the court: divorce, dissolution of marriage, obedience, maintenance, dower, succession, custodianship and/or guardianship over minors, etc. Usually in such cases, one of the parties, aided by a lawyer or a shar‘i advocate, files a suit against the other party.6 Abu Zayd (the acting chief clerk) sets the date for the court session (usually three to four weeks ahead in order to allow the defending party to prepare him/herself). Then, Abu ‘Uday (the assistant clerk) issues summonses for a specific day and hour, and either sends it by mail or otherwise gives it to the plaintiff or his/her delegate, for them to deliver it to the defendant. On the set date, assuming that summonses were delivered and signed by the parties, and that no party was motivated to absent him/herself from the court session, the litigants probably attend court, accompanied by relatives and by their legal representatives.7 After the qadi’s desk is cleared from mu‘amalat, hearings concerning substantive suits commence. The spatial arrangement of the courtroom in the court’s new residence is as follows: the qadi’s desk is placed on a raised platform, at the far side of the room. To his left, at a separate table on the platform perpendicular to the qadi’s desk, sits Salih—the court scribe (or rather, the court computer operator). On the floor in front and below the qadi’s platform, two tables are positioned at right angles to the qadi’s desk. These tables are two meters distance from each other, and are usually occupied by the legal representatives of the parties whose case is currently under consideration. Facing the qadi, several rows of wooden benches are arranged until the wall opposite to the qadi’s podium. The litigants sit in the front row, and the spectators (relatives, friends, etc.) sit in the rear. There are also benches attached to the left wall of the hearing room. All in all, a small crowd of up to 25 people may sit on the wooden benches and observe the hearings (see Figure 7.3). When a hearing is about to begin, the court scribe, Salih, opens a new MS-Word document (under the template which fits the case under consideration) and fills in the parties’ personal details (names of litigants and legal representatives, places of residence, ID numbers, etc.).8

Organizational Routines