Negligence and Novel Duty Situations

6

Negligence and novel duty situations

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

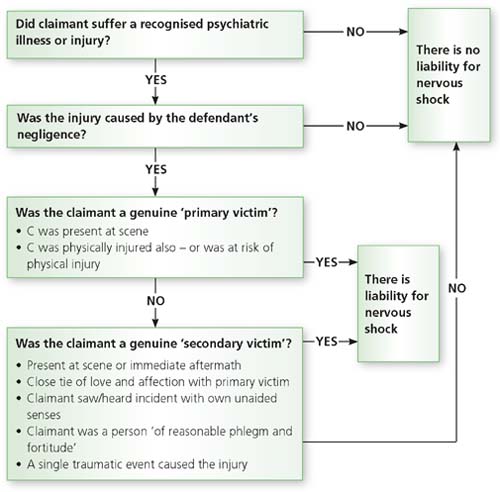

■ Understand the criteria for establishing the existence of a duty of care in relation to nervous shock (psychiatric damage)

■ Understand the restrictions on the scope of the duty

■ Understand the criteria for imposing pure economic loss

■ Understand the reasons for the reluctance for imposing liability for pure economic loss

■ Understand the criteria for imposing liability for economic loss caused by a negligent misstatement

■ Understand the limited circumstances in which the law is prepared to impose liability for a failure to act

■ Critically analyse each of these novel duty situations

■ Apply the law on each duty to factual situations and reach conclusions as to liability

We have already seen how the tort of negligence is based on the existence first of a duty of care owed by the defendant to the claimant. The law has developed over time to include many instances where a duty of care exists.

There are numerous straightforward relationships where we might naturally expect a duty of care to exist. These would include such relationships as those between fellow motorists, between doctor and patient, between employer and employee, between manufacturers of products and their consumers and, of course, there are many others. We have already seen examples in the case law of all of these.

There are also certain situations that are less obvious that have had to be considered by the courts where the duty arises more from specific circumstances than because of the relationship between the parties. They have proved to be more controversial but in some of them the courts have held that a duty of care does in fact exist. They include the following four major examples.

6.1 Nervous shock (psychiatric injury)

6.1.1 The historical background

This is another area of negligence that has been the subject of uncertain development. The extent to which liability has been imposed has expanded or contracted according to:

■ The state of medical knowledge, i.e. psychiatric medicine and the recognition of psychiatric disorders, has developed dramatically over the past 100 years; the great concern expressed in recent years over soldiers who were executed in the First World War is an interesting example of that.

■ Policy considerations on the part of judges, particularly the ‘foodgates’ argument, that to impose liability in a particular situation may lead to a rush of claims and so should be avoided whatever the justice of the case; this has had the effect of operating particularly harshly on secondary victims.

Actions failed in the last century for three specific reasons:

■ Because of the state of medical knowledge, psychiatric illness or injury was not properly recognised so there could be no duty if the type of damage concerned was not recognised.

■ Another problem of course was the fear that a person making such a claim could actually be faking the symptoms.

■ Finally there was the ‘foodgates’ argument, that once one claim was accepted it would lead to a multitude of claims.

CASE EXAMPLE

Victoria Railway Commissioners v Coultas [1888] 13 App Cas 222

Nervous shock resulting from involvement in a train crash did not give rise to liability, not least because of the ‘foodgates’ argument.

Even from the start there were two aspects to determining whether liability should be imposed:

■ First, the injury alleged must conform to judicial attitudes of what constitutes nervous shock, a recognised psychiatric disorder.

■ Second, the person claiming to have suffered nervous shock must fall into a category accepted by the courts as being entitled to claim.

6.1.2 Nervous shock, psychiatric injury and the type of recoverable damage

The claim must then involve an actual, recognised psychiatric condition capable of resulting from the shock of the incident and recognised as having long- term effects.

CASE EXAMPLE

Reilly v Merseyside Regional Health Authority [1994] 23 BMLR 26

The court would not impose liability when a couple became trapped in a lift as the result of negligence and suffered insomnia and claustrophobia after they were rescued. These could not be classed as recognised psychiatric illnesses.

CASE EXAMPLE

Tredget v Bexley Health Authority [1994] 5 Med LR 178

The parents of a child born with serious injuries following medical negligence and then dying two days later successfully claimed for nervous shock. The result of the case is perhaps surprising but the court held that they did indeed suffer from psychiatric injuries despite the defendants’ argument that their condition was no more than profound grief.

The courts in recent times have been prepared to accept a claim that is partly caused by grief and partly by the severe shock of the event.

CASE EXAMPLE

Vernon v Bosely (No. 1) [1997] 1 All ER 577

Here a father had witnessed his children being drowned in a car negligently driven by their nanny. His claim was successful and he recovered damages for nervous shock that was held to be partly the result of pathological grief and bereavement, but partly also the consequence of the trauma of witnessing the events.

6.1.3 The development of a test of liability

Originally claims were first allowed purely on the basis of foreseeability of a real and immediate fear of personal danger (the so- called ‘Kennedy’ test) so that the class of possible claimants was at first very limited.

CASE EXAMPLE

Dulieu v White & Sons [1901] 2 KB 669

The court accepted a claim when a woman suffered nervous shock after a horse and van that had been negligently driven burst through the window of a pub where she was washing glasses. She was able to recover damages because she had been put in fear for her own safety.

This limitation was later extended to include a claim for nervous shock suffered as the result of witnessing traumatic events involving close family members and therefore fearing for their safety.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hambrook v Stokes Bros [1925] 1 KB 141

A woman recovered damages for nervous shock when she saw a runaway lorry going downhill towards where she had left her three children, and then heard that there had indeed been an accident involving a child. The court disapproved the ‘Kennedy’ test and considered that it would be unfair not to compensate a mother who had feared for the safety of her children when she could have claimed if she only feared for her own safety.

CASE EXAMPLE

Dooley v Cammell Laird & Co [1951] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 271

A crane driver claimed successfully for nervous shock when he saw a load fall and thought that workmates underneath would have been injured.

Indeed claims have even been allowed where harm to the person with whom the close tie exists would be impossible.

CASE EXAMPLE

Owens v Liverpool Corporation [1933] 1 KB 394

Here relatives of a deceased person recovered damages for nervous shock when the coffin fell out of the hearse that they were following.

One restriction on this development was to prevent a party from recovering who was not within the ‘area of impact’ of the event.

CASE EXAMPLE

King v Phillips [1953] 1 QB 429

A mother suffered nervous shock when from 70 yards away she saw a taxi reverse into her small child’s bicycle and presumed him to be injured. Her claim failed because the court said she was too far away from the incident and outside the range of foresight of the defendant.

An alternative measure to the area of impact test is whether the claimant falls within the ‘area of shock’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Bourhill v Young [1943] AC 92

A pregnant Edinburgh fishwife claimed to have suffered nervous shock after getting off a tram, hearing the impact of a crash involving a motorcyclist, and later seeing blood on the road, after which she gave birth to a still- born child. The House of Lords held that, as a stranger to the motorcyclist, she was outside the area of foreseeable shock and her claim failed.

Successful claims for nervous shock have also been made even where the traumatic event is not an accident of some kind, as is usually the case in such claims. The same principle of reasonable foresight has therefore allowed for recovery in nervous shock claims even where the principal damage was to property rather than involving injury to or the safety of a person.

CASE EXAMPLE

Attia v British Gas [1987] 3 All ER 455

A woman who witnessed her house burning down when she arrived home was able to claim successfully for nervous shock. She was within the area of impact. The claim was said to be within the reasonable foresight of the contractors who negligently installed her central heating, causing the fire.

Traditionally it was well established in the case law that a rescuer was able to recover when suffering nervous shock.

CASE EXAMPLE

Chadwick v British Railways Board [1967] 1 WLR 912

When two trains crashed in a tunnel a man who lived nearby was asked because of his small size to crawl into the wreckage to give injections to trapped passengers. He was able to claim successfully for the anxiety neurosis he suffered as a result. This was largely explained on the basis that he was a primary victim, at risk himself in the circumstances.

Usually only professional rescuers will be able to claim or those present at the scene or the immediate aftermath.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hale v London Underground [1992] 11 BMLR 81

A fireman claimed successfully for post-traumatic stress disorder that he suffered following the King’s Cross fire.

However claims for shock suffered at the scene of disasters will not be successful in the case of those people considered only to be bystanders.

CASE EXAMPLE

McFarlane v E E Caledonia [1994] 2 All ER 1

A person who was helping to receive casualties from the Piper Alpha oilrig failed in his claim because he was classed as a mere bystander rather than a rescuer at the scene.

As we have seen the tests developed above involve the proximity of the claimant in time and space to the negligent incident or the closeness of the relationship with the party who is present. The widest point of expansion of liability came under the two- part test from Anns (see Anns v Merton LBC [1978] AC 728, at section 6.2.2), and allowed for recovery when the claimant was not present at the scene but was at the ‘immediate aftermath’. Inevitably ‘the meaning of immediate aftermath’ was open to an interpretation based on policy.

CASE EXAMPLE

McLoughlin v O’Brian [1982] 2 All ER 298, HL

A woman was summoned to a hospital about an hour after her children and husband were involved in a car crash. One child was dead, two were badly injured, all were in shock and they had not yet been cleaned up. The House of Lords held that since the relationship with the victims was sufficiently close and the woman was present at the ‘immediate aftermath’ she could claim. Lord Wilberforce identified a three- part test for secondary victims that was approved later in Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire [1992] 4 All ER 907 (see section 6.1.4).

6.1.4 Restrictions on the scope of the duty

In the very important and controversial case following the Hillsborough disaster the House of Lords reviewed all aspects of the duty. The ‘foodgates argument’ was clearly an important feature of their deliberations and the House identified a fairly restrictive set of circumstances in which a claim for nervous shock might succeed.

CASE EXAMPLE

Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire [1992] 4 All ER 907

At the start of a football match police allowed a large crowd of supporters into a caged pen as the result of which 95 people in the stand suffered crush injuries and were killed. Since the match was being televised much of the disaster was shown on live television. A number of claims for nervous shock were made. These varied between those present or not present at the scene, those with close family ties to the dead and those who were merely friends. The House of Lords refused all of the claims and identified the factors important to consider in determining whether a party might recover. These were:

■ The proximity of the relationship with a party who was a victim of the incident – a successful claim would depend on the existence of a close tie of love and affection with the victim, or presence at the scene as a rescuer.

■ The proximity in time and space to the negligent incident – there could be a claim in respect of an incident or the immediate aftermath that was witnessed or experienced directly, there could be none where the incident was merely reported.

■ The cause of the nervous shock – the court accepted that this must be the result of witnessing or hearing the horrifying event or the immediate aftermath.

Lord Ackner identified these restrictions as follows:

JUDGMENT

‘Because “shock” in its nature is capable of affecting such a wide range of persons, Lord Wilberforce in McLoughlin v O’Brian [1983] concluded that there was a real need for the law to place some limitation upon the extent of admissible claims and in this context he considered that there were three elements inherent in any claim.

1. The class of persons whose claims should be recognised.

Lord Wilberforce … contrasted the closest of family ties – parent and child and husband and wife – with that of the ordinary bystander. As regards [the former] the justifications for admitting such claims is the presumption, which I would accept as being rebuttable, that the love and affection normally associated with persons in those relationships is such that a defendant ought reasonably contemplate that they may be so closely and directly affected by his conduct as to suffer shock resulting in psychiatric illness. While as a generalisation more remote relatives and friends can reasonably be expected not to suffer illness from the shock, there can well be relatives and friends whose relationship is so close and intimate that their love and affection for the victim is comparable …

2. The proximity of the plaintiff to the accident.

It is accepted that the proximity to the accident must be close both in time and space. Direct and immediate sight or hearing of the accident is not required. It is reasonably foreseeable that injury by shock can be caused to a plaintiff, not only through the sight or hearing of the event, but of its immediate aftermath.

3. The means by which the shock is caused.

Lord Wilberforce concluded that the shock must come through sight or hearing of the event or its immediate aftermath.’

The case then identifies for the future the classes of claimants who will be successful and those who will not:

■ Primary victims – present at the scene of the shocking event and either injured or at risk of injury.

■ Secondary victims – present at the scene or its immediate aftermath and with a close tie of love and affection to the primary victim and having witnessed or heard the traumatic events with their own unaided senses.

■ It was also considered that secondary victims watching an event on live television that contravened broadcasting standards in relation to close up shots etc., might claim from the broadcasting authority.

Primary victims

Primary victims traditionally included those who were present at the scene and may suffer physical injury or their own safety was threatened. This was the situation in the landmark case of Dulieu v White [1901] 2 KB 669 where the woman could have been hurt by the horse coming through the glass window, and did in fact suffer a miscarriage as a result of the defendant’s negligence.

The primary victim need not suffer any physical injury. It is sufficient that he is present at the event causing the shock and is at risk of harm. Neither will it matter that the primary victim is more susceptible to shock. This contrasts with secondary victims who are compared with ‘a man of ordinary phlegm’ and will not be compensated if they are more likely to suffer psychiatric illness. The rules on both were considered in Page v Smith [1996] 3 All ER 272.

CASE EXTRACT

In the case extract below a significant section of the judgment has been reproduced in the left hand column. Individual points arising from the judgment are briefly explained in the right hand column. Read the extract including the commentary in the right hand column and complete the exercise that follows.

| Extract adapted from the judgment in Page v Smith [1995] 2 All ER 736 | |

| Facts | |

| The claimant was involved in a minor car collision which was through the defendant’s negligence. While the claimant suffered no physical injury, he suffered in consequence of the accident a recurrence of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). The House of Lords held that the defendant did owe the claimant a duty of care to avoid this injury. | The significant facts were: the defendant was negligent while no physical injury was suffered the claimant suffered a recurrence of a psychiatric injury. |

| Judgment | |

| LORD LLOYD | |

| This is the fourth occasion on which the House has been called on to consider ‘nervous shock’. On the three previous occasions, Bourhill v Young [1943] AC 92, McLoughlin v O’Brian [1983] 1 AC 410 and Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police [1992] 1 AC 310, the [claimants] were, in each case, outside the range of foreseeable physical injury … | Lord Lloyd recognises the significance of foreseeable physical injury to a successful claim. |

| In all these cases the [claimant] was the secondary victim of the defendant’s negligence. He or she was in the position of a spectator or bystander. In the present case, by contrast, the [claimant] was a participant. He was himself directly involved in the accident, and well within the range of foreseeable physical injury. He was the primary victim. This is thus the first occasion on which your Lordships have had to decide whether, in such a case, the foreseeability of physical injury is enough to enable the [claimant] to recover damages for nervous shock … | Previous House of Lords appeals failed because they involved secondary victims – but who ranked as mere bystanders. Page is first House of Lords case involving a primary victim. |

Though the distinction between primary and secondary victims is a factual one, it has, as will be seen, important legal consequences. So the classification of all nervous shock cases under the same head may be a misleading one … [T]he peculiarity of the present case is that [the claimant] suffered no … physical injury of any kind. But as a direct result of the accident he suffered a [recurrence] of an illness or condition known variously as ME, CFS or PVFS, from which he had previously suffered in mild form on occasions, but which, since the accident, has become an illness of ‘chronic intensity and permanency’ … | Question is whether foreseeability of physical injury is enough for claim for psychiatric injury only. Important to distinguish between primary victims and secondary victims because consequences different. |

We now know that the [claimant] escaped without external injury. Can it be the law that this makes all the difference? Can it be the law that the fortuitous absence of foreseeable physical injury means that a different test has to be applied? Is it to become necessary, in ordinary personal injury claims, where the [claimant] is the primary victim, for the court to concern itself with different ‘kinds’ of injury? | Critical fact is that Page suffered no physical injury – and only a recurrence of a psychiatric injury. |

Suppose in the present case, the [claimant] had been accompanied by his wife, just recovering from a depressive illness, and that she had suffered a cracked rib, followed by an onset of psychiatric illness. Clearly, she would have recovered damages for her illness, since it is conceded that the defendant owed the occupants of the car a duty not to cause physical harm. Why should it be that necessary to ask a different question, or apply a different test, in the case of the [claimant]? Why should it make any difference that the physical illness that the [claimant] undoubtedly suffered as a result of the accident operated through the medium of the mind, or of the nervous system, without physical injury? If he had suffered a heart attack, it cannot be doubted that he would have recovered damages for pain and suffering, even though he suffered no broken bones. It would have been no answer that he had a weak heart. | For primary victims the type of injury suffered does not matter as long as some type of injury is foreseen. |

Foreseeability of psychiatric injury remains a crucial ingredient when the [claimant] is a secondary victim, for the very reason that the secondary victim is almost always outside the area of physical impact, and therefore outside the range of foreseeable physical injury. But where the [claimant] is the primary victim of the defendant’s negligence, the nervous shock cases, by which I mean the cases following on from Bourhill v Young, are not in point. Since the defendant was admittedly under a duty of care not to cause the [claimant] foreseeable physical injury, it was unnecessary to ask whether he was under a separate duty of care not to cause foreseeable psychiatric injury. | But psychiatric injury must be foreseeable for secondary victims. |

[I]n claims by secondary victims … the courts have, as a matter of policy, rightly insisted on a number of control mechanisms. Otherwise, a negligent defendant might find himself being made liable to all the world … foreseeability of injury by shock is not enough. The law also requires a degree of proximity … not only … to the event in time and space, but also proximity of relationship [with] the primary victim … A further control mechanism is that the secondary victim will only recover damages for nervous shock if the defendant should have foreseen injury by shock to a person of normal | Claims by secondary victims have extra controls because of policy considerations. |

None of these mechanisms are required in the case of primary victims. Since liability depends on foreseeability of physical injury, there could be no question of the defendant finding himself liable to all the world. Proximity of relationship cannot arise, and proximity in time and space goes without saying. Nor in the case of a primary victim is it appropriate to ask whether he is a person of ‘ordinary phlegm’. In the case of physical injury there is no such requirement. The negligent defendant, or more usually his insurer, takes his victim as he finds him. The same should apply in the case of psychiatric injury. There is no difference in principle … between an eggshell skull and an eggshell personality. Since the number of potential claims is limited by the nature of the case, there is no need to impose any further limit by reference to a person of ordinary phlegm. Nor can I see any justification for doing so. | Alcock criteria. Also must be of normal phlegm and fortitude. But no such controls for primary victims. And eggshell skull rule applies to primary victims. |

KEY POINTS FROM PAGE V SMITH

■ Lord Lloyd identifies and confirms that it is essential first to distinguish between primary and secondary victims because different rules apply.

■ The case confirms the existing definition of primary victims:

■ that there is liability to a person present at the scene and suffering physical injury as well as psychiatric injury;

■ there is also liability to a person present at the scene and fearing for his own safety;

■ but only if suffering from a recognised psychiatric injury;

■ the definition of foreseeable harm for a primary victim needs only foresight of some injury.

■ The case also represents a development in the law because:

■ it does not have to be physical harm – and there is no reason to separate out physical and psychiatric harm;

■ the application of the ‘thin skull’ rule to nervous shock in the case of primary victims;

■ this contrasts with the requirement of ‘reasonable phlegm and fortitude’ for secondary victims;

■ and there is no application of hindsight in assessing claims for primary victims.

ACTIVITY

Apply the above principles in the following factual situation to determine in each case whether the claimant is a primary victim or a secondary victim or a mere bystander and how likely they are to succeed in the circumstances:

Through the negligent maintenance of its premises by his employer’s, Witless Engineering, Victor is badly injured when a section of steel staircase and walkway collapses on him. He dies two hours later in hospital from his very serious crush injuries.

Consider the possibility of each of the following succeeding if they claim against Witless Engineering for psychiatric damage (nervous shock):

a. Ali, Victor’s closest friend, who is present in the factory at the time of the accident, and sees the staircase and walkway collapse on to Victor from his machine on the other side of the factory. Ali suffers post-traumatic stress disorder as a result.

b. Bernard, Victor’s son, who also works in the factory on the machine next to Ali and who suffers grief after seeing the extent of Victor’s injuries.

c. Cath, Victor’s mother, who is on holiday at the time of the accident, and is told about her son’s death ten days later on her return to England, and who suffers severe depression as a result.

d. Denzil, a fire officer who cut Victor from the wreckage. At all times there was a danger that more of the walkway would collapse and so it was vital that Denzil cut Victor from the wreckage as quickly as possible for Victor to have any chance of surviving. Denzil suffers post- traumatic stress disorder as a result.

One consequence of the application of the ‘thin skull’ rule in Page v Smith is that a psychiatric injury that follows a physical injury will rarely be considered unforeseeable and therefore too remote a consequence of the breach.

CASE EXAMPLE

Simmons v British Steel [2004] UKHL 20

Following an industrial injury caused by his employer’s negligence the claimant suffered a worsening of his psoriasis, a stress related skin disease, and of a depressive illness, also leading to a personality change. This resulted from his anger at his employer’s lack of apology and lack of support, rather than from the injury itself. However, the court imposed liability for both types of injury even though, as the court admitted, the psychological injuries were not reasonably foreseeable, because the claimant was a primary victim.

Secondary victims

These are people who are not primary victims of the incident but who are able to show a close enough tie of love and affection to a victim of the incident and who witnessed the incident or its ‘immediate aftermath’ at close hand. The probable limit of this is in McLoughlin v O’Brian. In Alcock the judges were reluctant to allow claims because of lack of proximity both in time and space to the incidents at Hillsborough and turned down claims from people who had identified bodies in the morgue some time after the events of the match. Indeed the courts have engaged in some fairly fine distinctions as to what can acceptably be called ‘the immediate aftermath’ in later cases.

CASE EXAMPLE

Taylor v Somerset HA [1993] 4 Med LR 34

The claimant’s husband suffered a fatal heart attack while at work. She was told only that he had been taken to hospital and when she arrived at the hospital she was told that he was dead. She was so shocked that she would not believe he was dead until she identified his body in the mortuary. She later suffered a psychiatric illness and claimed against the hospital. Even though she was at the hospital within an hour her action failed. The court held that the actual purpose for her visit was to identify the body so that it was not to do with the cause of his death.

Rescuers

These may well of course be primary victims and at risk in the circumstances of the incident causing the nervous shock. Traditionally in any case courts tended to treat professional rescuers as primary victims.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hale v London Underground [1992] 11 BMLR 81

A fireman who had been involved in the rescue of victims at the King’s Cross fire suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and recovered damages for nervous shock.

However, the question of who qualifies as a rescuer and will be able to recover damages has been subject to some uncertain development.

CASE EXAMPLE

Duncan v British Coal [1990] 1 All ER 540

There was surprisingly no liability where a miner saw a close colleague crushed in a roof fall that was the fault of the employers, and tried unsuccessfully to resuscitate him.

CASE EXAMPLE

White v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire [1998] 1 All ER 1, HL

Police officers who claimed to have suffered post- traumatic stress disorder following their part in the rescue operation at the Hillsborough disaster were denied a remedy by the House of Lords. The reasoning seems to be that they did not actually put themselves at risk, and that public policy prevented them from recovering when the relatives of the deceased in the disaster could not.

As a more recent alternative the courts have been willing to accept that a rescuer can also claim as a secondary victim. However, this will only be possible where the rescuer conforms to all of the requirements for secondary victims laid out in Alcock.

CASE EXAMPLE

Greatorex v Greatorex [2000] 4 All ER 769

Here a fire officer attended the scene of an accident caused by the negligence of his son. When he was required to attend to his son he claimed afterwards to suffer nervous shock. The court would not accept the claim because of the conflict that it would cause between family members, but had the son not been the cause of the accident a claim may have been possible in the circumstances.

So the fact that a person can prove that they are a rescuer is insuffcient on its own to claim unless they can also prove that they are either a genuine primary victim or a genuine secondary victim.

CASE EXAMPLE

Stephen Monk v PC Harrington UK Ltd [2008] EWHC 1879 (QB)

The claimant helped two workers who were injured when a platform fell on them during the building of the new Wembley Stadium. The court denied him damages for psychiatric injury. While the court accepted that the man did act as a rescuer, it would not accept his argument that he was a primary victim because he felt that he had caused the accident as he was responsible for supervision of the platform that fell. The court felt that he was unlikely to have believed at any time that he was in danger.

Those unable to claim

The tests developed by the courts have meant that different classes of victims of nervous shock are unable to claim even though their injury and their right to a claim may seem legitimate. These can be classified in specific groups.

Bystanders

The law has always made a distinction between rescuers or people who are at risk in the incident and those who are merely bystanders and have no claim. This point goes back as far as Bourhill v Young [1943] AC 92.

CASE EXAMPLE

McFarlane v EE Caledonia Ltd [1994] 2 All ER 1

A person on shore receiving survivors from the Piper Alpha oilrig disaster was not classed as a rescuer and therefore had no valid claim despite suffering nervous shock.

Secondary victims with no close tie of love and affection to the victim

Alcock identified that in some relationships a close tie can be presumed. These might include parents and children and spouses. In all other cases a claimant would need to prove the tie and this led to claims failing in Alcock even where the primary victim was a close relation.

Workmates who witness accidents involving their colleagues will not be able to claim because any ties are not close enough to involve foreseeable harm.

CASE EXAMPLE

Robertson and Rough v Forth Road Bridge Joint Board [1995] IRLR 251

Three workmates had been repairing the Forth Road Bridge during a gale. One of them was sitting on a piece of metal on a truck when a gust of wind blew him off the bridge and he was killed. His colleagues who witnessed this were unable to claim. They were held not to be primary victims and had insufficient ties with the dead worker for injury to be foreseeable.

Secondary victims not present at the event or its immediate aftermath

A major control mechanism from both McLoughlin and Alcock in restricting claims by secondary victims is that the shock must result from being present at the scene of the event or its immediate aftermath. The mechanism has been used to defeat many claims but a range of recent decisions appear to have given a broader definition to the term ‘immediate aftermath’.

While Alcock claims were defeated because they exceeded the two hours accepted as immediate aftermath in McLoughlin, a period of 24 hours has subsequently been accepted as falling within the criteria and giving rise to liability.

CASE EXAMPLE

Farrell v Merton, Sutton and Wandsworth HA [2000] 57 BMLR 158

A woman recovered damages for nervous shock when doctors had negligently caused damage to her new-born baby. The shock she suffered on witnessing the child fell within the immediate aftermath because doctors had prevented her from seeing the child until the day after the birth.

There has even been some stretching of the meaning of witnessing the event or its immediate aftermath.

CASE EXAMPLE

Froggatt v Chesterfield and North Derbyshire Royal Hospital NHS Trust [2002] WL 3167323

A woman had a breast surgically removed after she was negligently diagnosed as suffering from breast cancer and obviously recovered damages. Her husband successfully claimed for nervous shock even though this actually occurred the first time that he saw her undressed afterwards. Her son also claimed successfully for the shock caused when he heard a telephone conversation in which his mother had identified that she had cancer and might die.

It has even recently proved possible for a claim to succeed where the psychiatric injury has resulted from another form of inconvenience or distress that itself has resulted from the traumatic event.

CASE EXAMPLE

McLoughlin v Jones [2001] EWCA Civ 1743

The claimant here was wrongly convicted and also imprisoned as a result of his solicitor’s negligence. The claimant suffered psychiatric injury as a result of the trauma involved and the solicitor was held liable.

CASE EXAMPLE

Howarth v Green [2001] EWHC 2687 (QB)

The claimant suffered nervous shock after being hypnotised in front of the audience. The court held that a psychiatric injury was a foreseeable consequence of the activity and held the hypnotist liable.

Perhaps the most remarkable development is that the courts now seem prepared to accept that the shocking event itself can last over a considerable period of time.

CASE EXAMPLE

North Glamorgan NHS Trust v Walters [2002] EWCA Civ 1792

Doctors negligently failed to diagnose that a ten-month-old baby suffering from hepatitis required a liver transplant. His mother was reassured that he would be unlucky not to recover; however, he suffered a major ft in front of her. They were both then taken to a London hospital for the child to have a liver transplant and on arrival it was discovered that the child had irreversible and severe brain damage. The parents’ permission was gained to switch off life support and the baby died minutes later in its mother’s arms. The whole episode took 36 hours and the mother suffered pathological grief, recognised as a psychiatric illness, as a result, and sued successfully. The defendants appealed on the grounds that the psychiatric injury was not brought about as a result of witnessing a single shocking event. The Court of Appeal rejected this argument and held that the whole period from when the baby suffered the ft to when it died was ‘a single horrifying event’. The trial judge was correct to conclude that the appreciation of the horror was sudden because seeing the ft, hearing that the baby was irreversibly brain damaged and the recommendation to end life support all had an immediate impact and were part of a continuous chain of events. The case could therefore be distinguished from those cases involving a gradual realisation of shocking consequences over a period of time.

Walters was referred to in Atkins v Seghal [2003] EWCA Civ 697 where a mother was told of her daughter’s death by a police officer but did not see the body until two hours later. The Court of Appeal accepted that this still represented the immediate aftermath.

The House of Lords has also shown its willingness to develop the area of nervous shock in quite dramatic fashion. Recent case law suggests that the House will even be prepared to accept a claim for negligence causing nervous shock in circumstances where the claimant is a secondary victim, but the last two controls under Alcock, present at the event or its immediate aftermath and witnessing the event with own unaided senses, are arguably not satisfied.

CASE EXAMPLE

W v Essex and Another [2000] 2 All ER 237