Mortgages

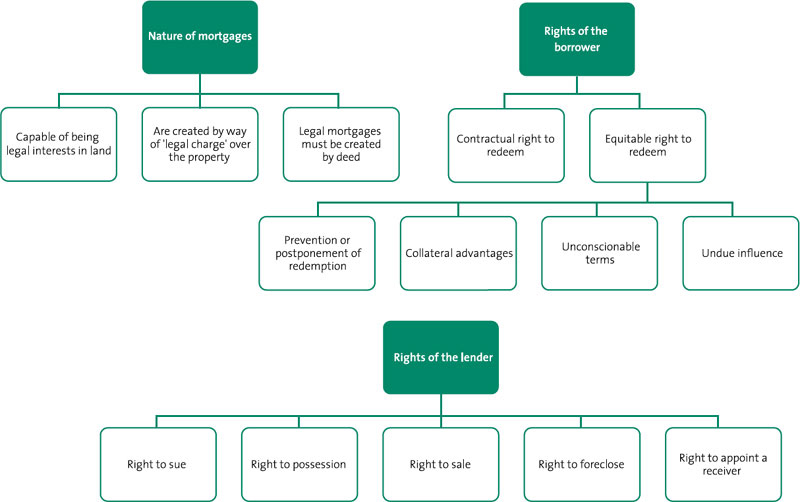

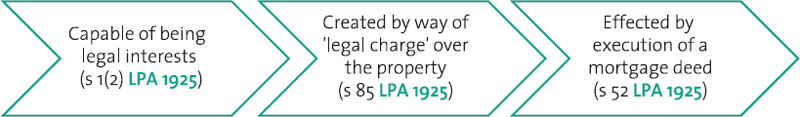

The common definition of a mortgage is that it is a loan of money secured against property; but in legal terms it is also one of the five classes of legal interest in land listed in s 1(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

A legal mortgage is created by ‘legal charge’, under s 85 LPA 1925, effected by the execution of a mortgage deed (s 52 LPA 1925).

Mortgages are:

Understanding: the rights of the borrower

The borrower’s rights under the terms of the mortgage are divided into rights that are legal in nature and those that take effect in equity.

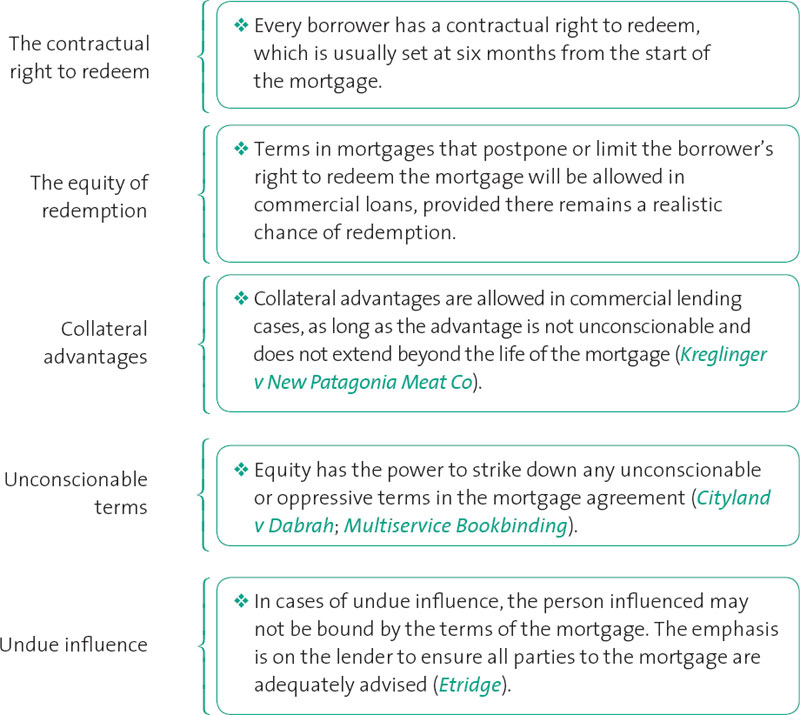

The contractual right to redeem

The borrower under a mortgage has one contractual right, which is the right to redeem, or pay off, the mortgage. The contractual right to redeem the mortgage is commonly set out in the mortgage deed as being six months from the start of the mortgage, even though the repayment schedule of the mortgage commonly allows for it to be repaid over a significantly longer period (usually 25 years).

Aim Higher

You may wonder what the significance is of the contractual right to redeem. Under the strict rules of contract law, if the borrower misses the date of redemption set out in the mortgage deed, they are technically in breach of contract. As such they forfeit their security under the terms of the loan, which means the lender can take their house.

The equitable right to redeem

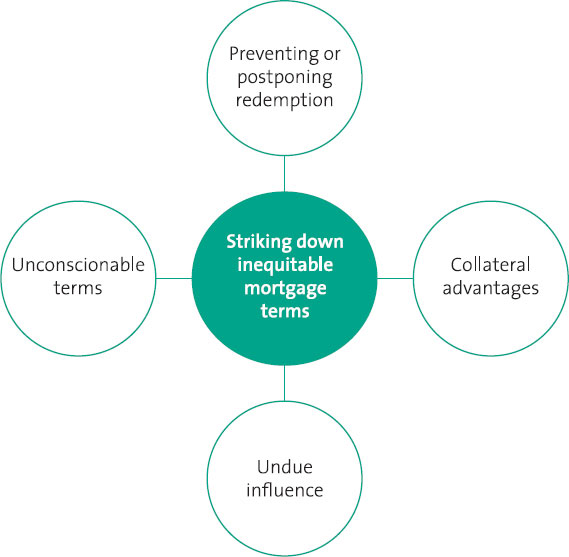

In equity, as long as the borrower pays back the loan together with interest due on the mortgage at the contractually specified rate, then they will have a continued right to redeem the mortgage right up until the end of the mortgage term. As such, any terms in the mortgage that have the effect of preventing the loan from being repaid will be struck out by the courts.

The prevention or postponement of redemption

In spite of this, equity will allow the repayment of a commercial mortgage to be postponed or limited, provided:

the mortgage is not in any other way unconscionable; and

the mortgage is not in any other way unconscionable; and

the right to redeem is not rendered an illusion.

the right to redeem is not rendered an illusion.

Case precedent – Knightsbridge Estates Trust Ltd v Byrne [1940] AC 613

Facts: A company took out a mortgage over freehold property. The mortgage deed contained a term that the mortgage was to be repaid over a period of 40 years; however, the borrower wanted to repay the loan early. Held: The court found in favour of the lender. Whilst the 40-year loan period was relatively long, it was not unconscionable because this was a commercial transaction and the parties knew what they were doing. It was not the place of equity to intervene simply because the borrower felt that they had made a bad bargain.

Principle: Equity will allow the repayment of a commercial mortgage to be postponed or limited, provided it is not in any other way rendered unconscionable or rendered an illusion.

Application: Use this case to show how early redemption of a commercial mortgage can be prevented.

Case precedent – Fairclough v Swan Brewery Co Ltd [1912] AC 565

Facts: A pub landlord held the lease of a pub that had only 20 years left to run. He took out a mortgage over the pub that contained a provision preventing the landlord from redeeming the mortgage until six weeks before the end of the term of the lease. Held: The landlord should be allowed to redeem the mortgage early. The term in the mortgage deed had rendered the right to redeem an illusion.

Principle: Equity will allow the repayment of a commercial mortgage to be postponed or limited, provided it is not rendered an illusion.

Application: Use this case to illustrate a situation in which a term in a commercial mortgage will be struck down.

Think about why the two cases had such contrasting outcomes. In Knightsbridge Estates v Byrne [1940], the property was freehold land and so at the end of the 40-year period, the borrower would get back no less than what they had mortgaged in the first place. In contrast, in Fairclough v Swan Brewery [1912], because the borrower was prevented from redeeming the mortgage until the lease was about to come to an end, the borrower would have nothing to recover: no sooner would he have paid off his mortgage than he would have to return the property to the freeholder.

Collateral advantages

A collateral advantage is a benefit over and above simple security for the loan. Again, in commercial transactions, equity will allow limited collateral advantages to exist, provided that the collateral advantage should:

1. stop when the mortgage is redeemed; and

2. not be unconscionable.

Case precedent – Biggs v Hoddinott [1898] 2 Ch 307

Facts: A mortgage of a hotel contained a provision that the loan should not be repaid within the first five years, and that within this time the borrower should sell only the lender’s own brand of beer. Held: The agreement did not unfairly compromise the borrower’s right to redeem, because it only applied during the period of the mortgage.

Principle: Equity will allow limited collateral advantages to exist in commercial transactions.

Application: Compare the facts of this case against your own scenario to support your argument that a collateral advantage will be upheld by the courts.

Case precedent – Noakes & Co Ltd v Rice [1902] AC 24

Facts: A pub landlord had entered into a mortgage that required him to supply only the brewery’s products for the duration of the leasehold term, regardless of when the mortgage was repaid. Held: The term created an unfair collateral advantage because it did not end upon repayment of the loan.

Principle: Equity will allow collateral advantages to exist in commercial transactions, provided they stop when the mortgage is redeemed.

Case precedent – G&C Kreglinger v New Patagonia Meat and Cold Storage Co Ltd [1914] AC 25

Facts: The meat company mortgaged its property to a wool broker. One of the terms of the mortgage agreement was that the meat company would give the wool brokers a right of first refusal on their sheep skins for a period of five years. After only two years, the meat company redeemed the mortgage, paying back all the monies owing under it. It then argued that the agreement to sell the sheep skins to the lender should cease. Held: The collateral advantage was valid.

Principle: Equity will allow limited collateral advantages to exist, provided that they are not unconscionable.

Application: Use this case to support your argument that a collateral term in a mortgage will be upheld.

In Kreglinger v NewPatagonia Meat Co [1914] the collateral advantage was held to be valid by the court because:

1. five years was not a particularly long time to be tied into the agreement;

2. the price to be paid for the skins was a reasonable market price; and

3. it was an arm’s length business transaction.

However, as an equitable remedy, the striking down of collateral advantages is discretionary and each case will turn upon its own facts.

Unconscionable terms

On a more general basis, equity has the power to strike down any unconscionable or oppressive terms in the mortgage agreement.

Case precedent – Cityland & Property (Holdings) Ltd v Dabrah [1967] 3 WLR 605

Facts: A company bought land with the help of a mortgage. There was no interest payable on the mortgage, but instead the lender required a premium of 57 per cent of the amount of the loan, repayable over six years. Held: The term was unreasonably oppressive not only because of its size, but also because of the relative bargaining positions of the borrower and lender. It was obvious that the borrower had been desperate for the loan and that the lender had taken advantage of this.

Principle: Equity will strike down any unconscionable or oppressive term in a mortgage agreement.

Application: Give this case as an example of an unconscionable term in a mortgage.

Case precedent – Multiservice Bookbinding Ltd v Marden [1978] 2 WLR 535

Facts: A mortgage of a business contained an unusual clause which imposed an ‘uplift’ payment calculable on the loan and index-linked to the Swiss franc. The effect of the uplift clause in conjunction with the other clauses in the contract was that the interest rate payable by the company was actually around 33 per cent. Held: The uplift clause was not an unconscionable term. The uplift clause could only be viewed as unconscionable if it were imposed in a morally reprehensible manner. The parties were in equal bargaining positions and so this kind of blame could not be apportioned to the lender. The borrower had simply made a bad bargain.

Principle: Equity will strike down any unconscionable or oppressive term in a mortgage agreement.

Application: Use this case to illustrate a situation in which an onerous term in a mortgage will not be held unconscionable by the courts.

What the court was saying, in effect, was that the lender has to have taken clear advantage of its position in order for the term to be unconscionable. This is quite a high bar that the courts impose in relation to business mortgages.

Undue influence

The most common situation in which equity steps in on behalf of homeowners is where there has been undue influence exerted upon one borrower by another.

Case precedent – Barclays Bank v O’Brien [1993] 3 WLR 786

Facts: A wife signed a deed giving the bank a second legal mortgage over the family home. When the bank sought to enforce payment of the loan, the wife claimed undue influence. Held: There had been undue influence and the bank had constructive notice of this. Whilst the bank had written to the wife advising her to take independent legal advice, they did not check that this had happened; nor had they explained to her the implications of the second mortgage. Unless the bank could prove that it had taken reasonable steps to satisfy itself that the wife had entered into the agreement freely, the bank would be unable to enforce the loan.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the basic position of the courts in cases of undue influence.

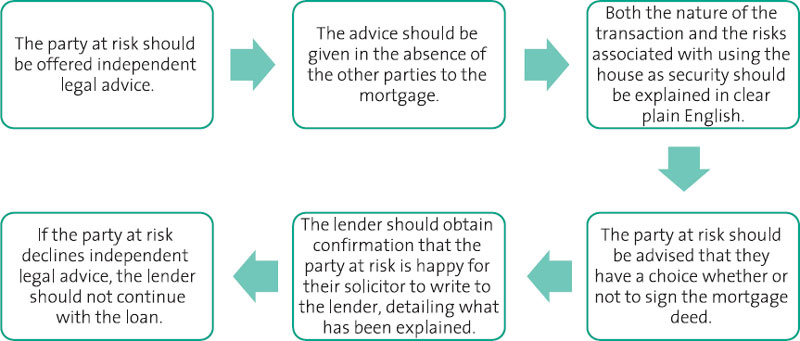

Following the finding in Barclays v O’Brien, the House of Lords in Royal Bank of Scotland plc v Etridge (No. 2) [2001] set out definitive guidance on what a lender should do in order to discharge this duty where there was a possibility of undue influence.

The Lords stated firstly that the burden of proof when claiming undue influence was on the person claiming to have been influenced. However, the bank would nevertheless be put on inquiry of the possibility of undue influence wherever a wife offered to stand surety for her husband’s debts. Thus there is a clear responsibility on the lender to take action to ensure proper advice has been given to all parties to the mortgage.

The diagram below details the kind of advice that should be given to any party who may be at risk from undue influence:

Aim Higher

It is important to remember that the guidelines are designed to prevent the lender from losing their security for the mortgage loan. It is therefore vital that banks follow these if they are to steer clear of legal difficulties if the issue of undue influence arises. There is a lot more detail given in Lord Nicholls’ judgment in Etridge and it is worth reading through it to get a full picture of the requirements.

Points to remember about the rights of the borrower

The right to sue

Any legal mortgage carries with it the contractual right to sue on the debt. Suing in contract for the debt is often pointless, however, because the reason the borrower is behind on payments is usually because they are in financial difficulty.

The right to possession

Unless the mortgage agreement provides to the contrary, in equity the lender has the right to possess the mortgaged property immediately the mortgage agreement has been finalised. The borrower does not have to have fallen into mortgage arrears for this right to exist.

‘The mortgagee may go into possession before the ink is dry on the mortgage.’

Per Harman J

Four Maids v Dudley Marshall (Properties) Ltd [1957] 2 WLR 531

A lender can take possession of mortgaged property either by peaceable re-entry or by court order. The lender will usually apply for a court order, however, because they risk being guilty of a criminal offence if they are found to have used or threatened violence for the purpose of securing entry to the mortgaged property (s 6(1) Criminal Law Act 1977).