Medical Certification

6

Medical Certification

Health is not valued till sickness comes.

Dr Thomas Fuller, 1654–1734

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should:

1. understand the requirement to obtain and maintain a medical certificate;

2. know the different types of medical certificates and the criteria for each;

3. have a working knowledge of the available alternatives to obtain a medical certificate in the event that you are medically disqualified;

4. recognize the severe penalties associated with falsification of medical applications; and

5. realize the impact of alcohol and drug use on your medical certificate.

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 5 discussed the importance of operating in accordance with the FARs. This chapter discusses an equally significant topic. Any person exercising the privileges of an airline transport pilot certificate, commercial pilot certificate, private pilot certificate, recreational pilot certificate, flight instructor certificate (when acting as pilot in command if serving as a required pilot flight crewmember), flight engineer certificate, flight navigator certificate, student pilot certificate, or ATC certificate must hold a valid medical certificate. Mechanics are not required to have one. The FAA, or its predecessor agencies, has been involved in civil aeromedical issues since 1926; in fact, the first “Disqualifying Conditions” were published that year.

Obtaining and maintaining a current medial certificate is required for those involved in certain aviation professions. If you are not able to obtain a medical certificate or have health problems that prevent you from retaining it, you will be disqualified from exercising your privileges. Two regulatory Parts, 61 and 67, address medical certification. Part 91 has regulations pertaining to drug and alcohol issues. As medical issues are critical for those involved in the profession, the relevant sections of Parts 61, 67, and 91 should be thoroughly reviewed.

This chapter covers the various classes of certificates, standards required of each certificate, the process of obtaining the proper certificate, disqualifying medical conditions, alternatives to normal procurement, falsification issues, and drug/driving under the influence (DUI) matters. We end with a checklist of items to consider in preparation for the aviation medical exam.

EXCEPTIONS

The FAA requires most persons involved in flight to hold valid medical certificates. The type of certificate required depends largely on the type of flight activity an individual is engaged in. There is no constitutional right requiring the government to issue as medical certificate. While the government must be fair in the issuance process due to constitutional concerns, the law considers flight a privilege and not a constitutional “right.” Therefore, these privileges are discretionary and government bodies may impose reasonable restrictions on those engaging in flight activity. Therefore, a pilot’s recourse, if denied a medical certificate, is limited to administrative appeal.

Not all pilots are required to possess a medical certificate. Sport pilots are not required to hold one. All that is required of a sport pilot is possession of a current and valid US driver’s license. While a medical certificate is not required, a student pilot training for the Sport Pilot Certificate must obtain a Student Pilot Certificate prior to solo flight. This certificate may be issued by the local Flight Standard District Office or an FAA Designated Flight Examiner.

Sport pilots may only exercise privileges in single-engine airplanes, gliders, lighter-than-air balloons or airships, gyroplanes, and a few other narrow categories. Sport pilot aircraft are further restricted by maximum gross takeoff weight (1,320 lb or 1,430 lb for seaplanes); maximum stall speed of 51 mph (45 knots); maximum speed in level flight of 138 mph (120 knots); single or two-seat aircraft only; fixed or ground-adjustable propellers; and unpressurized cabins. Ironically, those sport pilots who have lost (revoked, withdrawn, or suspended) or been denied an FAA medical certificate before application for the Sport Pilot Certificate are not allowed to operate using their driver’s license until they clear their airman record by having a valid third-class medical certificate issued.1 Those instructing sport pilots, or Sport Pilot Examiners (SPEs), must maintain a current FAA flight instructor certificate and a valid US driver’s license or an airman medical certificate.

Likewise, glider and balloon pilots are not required to hold a medical certificate of any class. To be issued glider or balloon airman certificate, the applicant simply certifies that he or she has no known physical defect that makes him or her unable to pilot a glider or balloon. Therefore, mechanics, sport pilots, and glider and balloon pilots are exempted from the medical certificate requirements.

TYPES OF CERTIFICATES

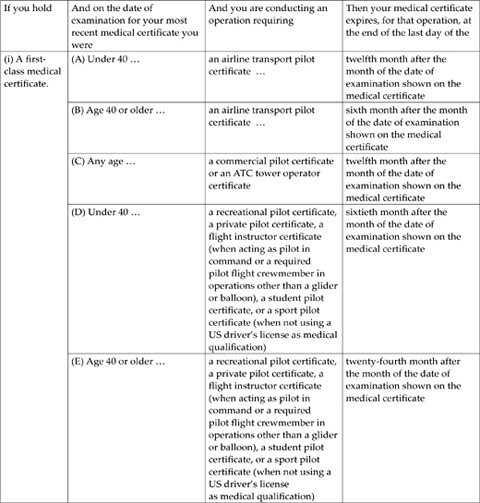

As mentioned above, the type of certificate required depends on the type of activity engaged in. Medical certificates are categorized by the FAA by “class.” Generally, first-class certificates are for the airline transport pilot; second-class certificates are for the commercial pilot (and air traffic controllers); and third-class certificates are for the student, recreational, and private pilot. All airmen are required to take the same exam; the class of certificate simply determines what type of medical standards you will be held to.

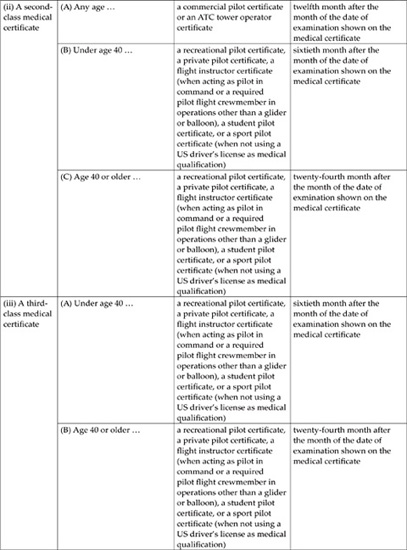

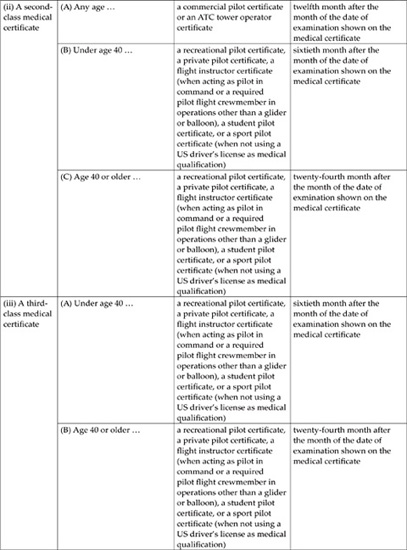

The second-class certificate is required for commercial, non-airline duties (e.g. for crop dusters or corporate pilots) and is valid for one year plus the remainder of the days in the month of examination. Those exercising the privileges of a flight engineer certificate, a flight navigator certificate, or employed as air traffic controllers must also maintain at least a second-class airman medical certificate. Much like the first-class certificate discussed above, a second-class medical certificate’s period of validity depends on the nature of use and age of the holder. A second-class certificate is valid for the remainder of the month of issue, plus 12 calendar months for operations requiring a second-class medical certificate, or 24 calendar months for operations requiring a third-class medical certificate if the airman is aged 40 or over on or before the date of the examination, or 60 calendar months for operations requiring a third-class medical certificate if the airman has not reached the age of 40 on or before the date of examination.

A third-class airman medical certificate is required to exercise the privileges of a private pilot certificate, a recreational pilot certificate, a flight instructor certificate, or a student pilot certificate. A third-class medical certificate is valid for the remainder of the month of issue, plus 24 calendar months for operations requiring a third-class medical certificate if the airman is aged 40 or over on or before the date of the examination, or 60 calendar months for operations requiring a third-class medical certificate if the airman has not reached the age of 40 on or before the date of examination. A third-class medical certificate’s period of validity depends solely on the age of the holder.2

In summary, listed below are the three classes of airman medical certificates, identifying the categories of airmen certificate applicable to each class:

1. First-class – Airline Transport Pilot.

2. Second-class – Commercial Pilot, Flight Engineer, Flight Navigator, or Air Traffic Control Tower Operator (note: this category of air traffic controller does not include FAA employee ATC specialists).

3. Third-class – Private Pilot, Recreational Pilot, or Student Pilot.

The following table illustrates the duration for each class of medical certificate.

Table 6.1 Medical certificate duration guide

It has not been possible to amend this table for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472445629Table6_1.pdf

REGULATORY BASIS

The regulations regarding certification are found in CFR 14 Part 61 and 67. Part 61 prescribes the requirements, conditions, privileges, and limitations for issuing pilot, flight instructor, and ground instructor certificates, ratings, and authorizations; the conditions under which those certificates, ratings, and authorizations are necessary; and the privileges and limitations of those certificates, ratings, and authorizations. Part 67 pertains to the medical standards and certification procedures for issuing medical certificates for airmen and for remaining eligible for a medical certificate. Regulations regarding alcohol and drugs are found in CFR 14 Part 91.

OBTAINING A CERTIFICATE

There are no minimum or maximum ages for obtaining an airman medical certificate. Any applicant who is able to pass the exam may be issued a medical certificate. However, since 16 years is the minimum age for a student pilot certificate, people under 16 are unlikely to have practical use for one.

The FAA has a two-step process for determining if someone is medically fit to operate an aircraft. The first step begins with a physical by a doctor with training in aviation medicine. Prospective certificate holders are required to complete a medical history and undergo a physical examination by a certified Aviation Medical Examiner (AME). AMEs are not government physicians; they are simply FAA designees. Over 5,000 AMEs have been designated by the FAA to take applications, give exams for, and issue FAA medical certificates. The AME process is actually fairly simple. You first contact an AME of your choice. You can locate an AME through the FAA website, where an updated database is maintained, or call your local FSDO for suggestions.3 Prior to the actual physical, you are required to complete an FAA application called a Form 8500-8. This form can be completed at the doctor’s office or electronically online. The MedXPress system allows anyone requiring an FAA Medical Certificate or Student Pilot Medical Certificate to electronically complete the 8500-8. Information entered into MedXPress will be transmitted to the FAA and will be available for your AME to review at the time of your medical examination. After reviewing the medical history on Form 8500-8 and completing the physical exam on the prospective applicant, the AME may issue a medical certificate, deny the application, or defer the decision to the Manager of the Aerospace Medical Certification Division (AMCD) or the appropriate Regional Flight Surgeon (RFS). The vast majority of applications are approved immediately by the AME subject to review by the FAA. All applications are forwarded to the AMCD whether the AME issues the certificate or further initial review is required by the regional flight surgeon. The second step of the process is a review by the FAA. Most applicants meet the FAA standards. However, in the event that the certificate is denied, the airman has several options. An airman who is medically disqualified for any reason may be considered by the FAA for an Authorization for Special Issuance of a Medical Certificate. For medical defects that are static or non-progressive in nature, a Statement of Demonstrated Ability (SODA) may be granted in lieu of an Authorization for Special Issuance of a Medical Certificate. These exceptions are explained in greater detail below.

AUTOMATIC DISQUALIFYING CONDITIONS

Since 1926, the government, through various agencies, has restricted individuals with certain medical conditions from obtaining a medical certificate. Initially the disqualifying conditions were limited, but the list has grown over time.

There are two categories of disqualifying conditions in medical cases. The first category of “specifically disqualifying conditions” is set forth in the medical regulations found in FAR Part 67. Once it is established that an applicant for medical certification has a medical history or clinical diagnosis of: diabetes mellitus requiring hypoglycemic medication, angina pectoris, coronary heart disease that has been treated or, if untreated, that has been symptomatic or clinically significant, myocardial infarction (heart attack), cardiac valve replacement, permanent cardiac pacemaker, heart replacement, psychosis, bipolar disorder, a personality disorder that is severe enough to have repeatedly manifested itself by overt acts, substance dependence, substance abuse, epilepsy (seizures), disturbance of consciousness without satisfactory explanation of cause, or transient loss of control of nervous system function(s) without satisfactory explanation of cause, he or she cannot qualify for unrestricted medical certification.

In Part 67 cases, when the existence of a medical history or clinical diagnosis of a specifically disqualifying condition is beyond dispute, the NTSB has no alternative but to affirm the FAA’s certificate denial. If the FAA moves to dismiss a petition for review of a certificate denial filed by an applicant and provides indisputable evidence that the applicant has or has ever had a specifically disqualifying condition, the petition will be dismissed without a hearing. To be successful, the applicant must prove that there is no valid diagnosis or medical history of any of the conditions above – in other words, the prospective airman must establish that the condition cited by the FAA never existed and does not currently exist. If there is a genuine issue as to whether the specifically disqualifying condition cited by the FAA has ever existed, an NTSB administrative law judge will conduct a hearing, as outlined below, to resolve this question.

Once the existence of a disqualifying condition is properly established, unrestricted medical certification cannot be obtained and any improvement in the disqualifying condition is immaterial. At that point, the only avenue available for medical certification is through the special issuance process (explained further below). If a request for special issuance certification is denied by the FAA, once a disqualifying condition is established, the only recourse available to the applicant is to later make another request for special issuance status to the FAA supported by evidence showing sustained medical stability or improvement. The special issuance process is explained in more detail below.

The second category of medical condition that may result in a denial of unrestricted certification depends on an assessment of medical risk. Such conditions are not listed in FAR Part 67. In cases where a specifically disqualifying condition does not exist, the FAA may still deny unrestricted medical certification to an applicant where it is found that the symptoms associated with a certain disorder would make the applicant an unacceptable risk to air safety. In these cases, the burden of proving that the condition does not pose such a risk is still on the certificate applicant. The applicant must establish that, despite the medical condition in question, he or she is medically able to safely operate as an airman. As the mere existence of the alleged condition does not prohibit unrestricted medical certification according to Part 67, the general medical risk must be resolved at an evidentiary hearing before an NTSB ALJ. Here, the FAA will present expert medical testimony and documentary evidence to support its position that a genuine medical risk exists. The certificate applicant must provide his or her own expert medical testimony, and any other relevant medical evidence, to show that the condition in question is not characterized by symptoms which pose a legitimate risk to air safety. The testimony of doctors and other medical experts is of great importance to certificate applicants attempting to meet their burden of proof in these cases.

Appealing a Denial

Applicants denied airmen medical certification have appeal rights. An applicant whose medical certification is denied may request reconsideration of the decision by the Manager, the FAA Aerospace Medical Certification Division, or an FAA Regional Flight Surgeon. If the AME simply defers issuance of a certificate, the AMCD or the RFS, as appropriate, will automatically review the application and inform the applicant of the decision.

If the FAA denies an applicant based on a medical condition that is specifically disqualifying as set forth under Part 67, the denial is final and may be appealed to the NTSB. However, as mentioned above, the petition will be dismissed without a hearing if the existence of a medical history or clinical diagnosis of a specifically disqualifying condition is beyond dispute. The only hope in this case is that the FAA is wrong and the airman can prove he or she has no history or diagnosis of a Part 67 condition. If you believe that you are qualified for an unrestricted medical certificate, you should seek NTSB review of the FAA’s denial action. The NTSB has the statutory authority to review the FAA’s determination as to whether an individual is qualified for such certification, and the first and most important step in obtaining NTSB review of the FAA denial is to file a petition requesting review by the NTSB no later than 60 days from the mailing/postmark date of the FAA’s denial letter, with the Office of ALJs at the NTSB. The petition may be in the form of a letter. You must provide a copy of the FAA’s denial letter with the petition. You may, at the same time you are seeking NTSB review of the FAA’s denial of unrestricted medical certification, pursue special issuance certification from the FAA. The method to do this is discussed below. In such a case, you request that the NTSB hold your petition for review of the FAA denial of unrestricted certification in abeyance pending the outcome of a special issuance request. However, a petition for review of an FAA unrestricted medical certificate denial cannot be held in abeyance by the NTSB for more than 180 days from the date on which the FAA informed the applicant/petitioner of the denial of unrestricted certification. If the special issuance is denied, or the time period runs out, an NTSB ALJ will schedule and conduct a hearing on the question of the applicant’s eligibility for certification.

If the AMCD or the RFS deny an applicant based on a medical condition that is not specifically disqualifying then the applicant may appeal to the Federal Air Surgeon (FAS). An unfavorable decision by the FAS may be then be appealed to the NTSB. An ALJ will schedule and conduct a hearing on the question of the applicant’s eligibility for certification. If the ALJ’s decision is unacceptable to the applicant or the FAA (under either type of denial Part 67 or nonspecific disqualification), the matter may be appealed to the full Board. If the full Board affirms the denial of certification, the applicant may seek review by a US Court of Appeals. Following an adverse decision by a Court of Appeals, the applicant may ask for review by the US Supreme Court. However, as mentioned in Chapter 6, it is highly unlikely that the Supreme Court would ever grant such an appeal.