Legal Procedure

Legal Procedure

No person shall be . . . deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law . . .1

Categories of Law and Judicial Procedure

Overview

In chapter 1 we described governmental and legal structures and provided some terms to help you understand the court structure and function. In this chapter, we begin an explanation of how courts really work. We summarize procedures used in criminal, juvenile, civil, and appellate courts.

Legal procedure is not intuitive. It requires significant study to be able to understand and describe the workings of the justice system. In this chapter we hope to provide enough background that you may understand and accurately describe the working of the judicial system. Like the information from chapter 1, this information will help you understand and apply the laws described in the remainder of this text. It will also help you accurately describe court actions you may be required to report.

Judicial procedure is particularly important for mass communications professionals who are often called on to report and interpret trial events and to describe court decisions. As practitioners, we do not perform those tasks well. We hope a careful reading of this chapter allows you to avoid some of the more common mistakes made by others.

Categories of Law and Judicial Procedure

Laws can be categorized as either substantive or procedural. Substantive laws are principles for acceptable behavior. They describe the kinds of actions or omissions that are permitted or prohibited. They also describe the punishments that may be imposed for their violation. Procedural laws set out the legal rules for determining when and how the substantive laws will be applied. A statute proscribing murder and setting the penalty for murder is an example of substantive law. Procedural laws describe how a person accused of murder is to be treated by the government. They also establish the process for determining whether such a person can be legally held accountable and punished for that crime. In other words, procedural law sets the rules for trials and for appeals.

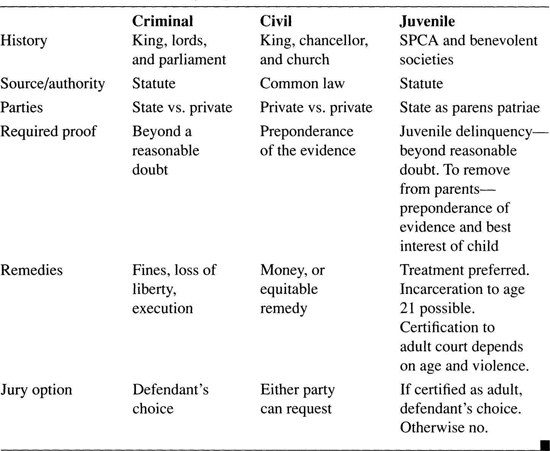

Procedural law varies depending on the kind of case that is being considered. Of course, procedural law is not identical in every state or jurisdiction. In order to provide a general understanding of how the courts work, we divide legal procedure simply into four major groups: criminal, juvenile, civil, and appellate procedure. The history and characteristics of criminal, juvenile, and civil law are summarized in Exhibit 2.1.

Exhibit 2.1. Summary of Legal Systems

Criminal laws are those substantive laws that are thought to be so important to the maintenance of a stable society that their violation carries serious penalties. Criminal laws are prosecuted in the name of the sovereign, either in the name of the people of the United States or in the name of the people of one of the 50 states. The United States or the individual state is the complainant and the person accused of a crime is the defendant. The government prosecutor has the burden of proof in a criminal case and must show the defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Civil laws were developed as part of the common law in England and have evolved through both common law and statute in the United States. Civil laws are enforced through lawsuits brought by a private individual against another private individual. In this context, corporations and some other business entities are “private individuals.” The person who initiates the suit is known as the plaintiff and the person against whom the suit is brought is called the defendant or respondent. The burden of proof in a civil case is on the plaintiff, who must prove the elements of his or her case by a preponderance of the evidence.

Juvenile laws are a relatively modern legal phenomenon. They relate to the treatment of people under the age of 18 who have committed criminal or antisocial acts, or who are themselves the victims of abuse or neglect. Under British common law, young people were treated just like adults and there is no mention of the rights of young people in the U.S. Constitution. Until the State of Illinois adopted the first juvenile laws in the United States in 1899, typically children either fell directly in the adult legal system or were treated as the property or responsibility of their parents.2 Occasionally, this resulted in such apparent mistreatment of children that benevolent societies were formed to challenge the judicial treatment of minors. Some of the earliest juvenile laws were actually modeled on laws initiated by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Contemporary juvenile laws vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but most combine aspects of both civil and criminal law. In some states, principles from sociology, counseling, and education are also applied in juvenile procedure. Juvenile law covers acts of delinquency, status offenses, and child welfare actions. It also involves unusual procedures that are neither purely criminal nor purely civil. Because of this mixture of purposes and practices, we treat juvenile procedure separately from criminal or civil procedure.

In virtually all legal matters, there is some system for appealing a court’s decision. After addressing criminal, juvenile, and civil procedure we describe appellate procedure and provide some additional information on the role of appellate courts and explain how decisions are made on appeal.

Criminal Procedure

Many states and the federal government use four categories of crime. The categorization of a specific crime depends on the state legislature’s judgment of the seriousness of the offense and the type of punishment that should be imposed for violations. Anyone responsible for reporting on crime should be familiar with the categories in his or her jurisdiction. The four general categories are felonies, misdemeanors, petty offenses, and juvenile offenses. Because we address juvenile procedure separately, here we only explain the first three.

Felonies are the most serious category of crimes. Felony violations usually carry both heavy fines and significant incarceration. Felony fines generally range from $2,000 to more than $10,000. Convicted felons are usually incarcerated in state or federal prisons for 3 years to life. In some jurisdictions, capital punishment can also be imposed for some felony violations. Felonies are often classified according to their severity with a number or letter. In most jurisdictions the lesser crimes have the highest numbers. For example, a Class 4 felony is not as serious an offense as is a Class 2 felony. Many jurisdictions add a letter designation, such as “Class X” felony, for the most serious offenses.

Misdemeanors are less offensive crimes. Violation of laws that have been classified by statute as misdemeanors often carry fines of $1,000 or less and/or incarceration for less than 1 year. Incarceration for misdemeanor offenses is usually served in a county or municipal jail, rather than in a state or federal prison.

The classification of petty offense is used by some jurisdictions for those crimes that are considered minimal. For example, Illinois classifies minor driving offenses such as speeding, improper lane use, and municipal code or county ordinance violations as petty offenses. Petty offenses are punished by fine only and the fines usually are less than $500. However, some states, as well as the federal government, have placed violations of industrial, corporate, and business regulations in this category. In some instances, fines of $10,000 per violation are possible and each day’s violation may be defined as a new violation. Under these circumstances, petty offense fines can be substantial. Some jurisdictions do not use the category of petty offense at all. In those jurisdictions, all crimes are either felonies or misdemeanors.

Pretrial Procedure

Before anyone charged with a crime goes to trial there are several steps of procedural law. These involve investigation, arrest, charging the defendant, and the pleadings that precede trial. Here we omit the investigation and only briefly describe arrest requirements. The judicial procedures of charging the defendant and the pleadings are covered in some detail because these are often the subjects of media coverage and litigation public relations. We include a description of negotiated disposition, sometimes called “plea bargaining,” because this process disposes of the vast majority of criminal charges.

Charge Documents

Before a defendant enters the criminal judicial process he or she must be charged with a crime. There are three ways a defendant can be charged: (a) warrantless arrest followed by formal charges, (b) indictment by grand jury, or (c) a prosecutor’s information or criminal complaint. In some states, all felonies must be charged by a grand jury and in most states, and in the federal system the most serious crimes are charged by a grand jury.

Warrantless Arrest. It is important to note the tremendous amount of discretion given to government officials to determine who is brought into the criminal justice system. Law enforcement officials, often, but not always, with the full knowledge and advice of the local prosecutor, decide who will be arrested without a warrant. These individuals may be charged based on the resulting police reports. Arrests that precede such court actions are called warrantless arrests. As might be expected, these decisions are often based on things other than whether an individual is actually guilty of committing a crime. Factors determining whether a person is arrested and submitted to the criminal process or is released without any charges at all, are often totally subjective. These factors include, but are not limited to, the officers’ on-the-spot perceptions and conclusions about the individual such as demeanor, social class and status, race, gender, age, and past experience with the police. Also, an individual’s physical appearance, clothing, neatness, and hygiene are significant predictors of police treatment. Therefore, no one should assume just because a person has been arrested and charged with a crime that she or he is guilty of any illegal conduct.

When a person has been arrested without a warrant, the prosecutor must review the police report and make a decision whether to charge the individual. Usually, this decision must be made within 48 hours. The suspect must then be brought before the nearest magistrate and informed of the pending charges.

Grand Jury Process. According to the U.S. Constitution “(n)o person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury.”3 Use of a grand jury to initiate criminal charges against a person is part of the common law system inherited from England. It has been adapted for use in the United States. Depending on the laws of the specific jurisdiction, a grand jury may consist of from 1 to more than 30 people who are called by the prosecutor to conduct an official investigation into the commission of crimes. Although in some jurisdictions, justices of the peace and magistrates conduct these proceedings, in most jurisdictions a judge will give the group its official duties and swear the individual members in as part of the panel. The judge rarely has any other official duties except to excuse or disband the group officially when the task is completed. Grand juries are summoned and authorized to conduct investigations over a specified period of time. At the end of its term, a grand jury is disbanded and a new group is sworn in to continue the process. In smaller jurisdictions, where serious crimes rarely occur, grand juries are summoned and convened only when needed. Grand jury members must be paid for their services, but the amount is usually very modest and often only covers or includes meals. Despite the low pay, the process can be expensive.

Unlike trial juries, grand juries are not chosen to be impartial. They are an investigative arm of the prosecution. Prosecutors either subpoena or recommend witnesses to the grand jury and only the prosecutor questions the witnesses who appear. Usually, only those individuals believed to have information about the commission of a crime, including the accused, are called to testify. However, in some jurisdictions, grand juries have been allowed to probe into collateral and tangential matters and some grand juries have been charged with overreaching or corruption for unjustified inquisition into private matters.

Individuals commanded to appear before grand juries by properly served subpoenas must comply or face arrest and contempt charges. Grand jury witnesses may hire an attorney to consult during their testimony. However, private attorneys are not permitted to ask questions or participate in the grand jury inquiry. They may also be required to sit outside the grand jury room. Under these circumstances, their client must ask to consult with the attorney prior to answering suspect or potentially incriminating questions. Witnesses before a grand jury are permitted to use their Fifth Amendment right not to answer any question that might incriminate them.

After the prosecutor has completed his or her presentation before the grand jury, the group convenes in sequestered chambers to decide whether there is sufficient evidence to indict or bring criminal charges. The prosecutor will have typically given the grand jury his or her recommendations and the statutory names of the crimes for which indictments are requested. The grand jury must decide if it agrees with the prosecutor’s request. If the grand jury does find sufficient probable cause against an individual, it returns what is called a True Bill of Indictment or a Bill of Indictment. Of course, a group of laymen who have only seen witnesses called by the prosecutor typically comply with the prosecutor’s recommendations. If insufficient information has been presented to convince the grand jury of probable cause a No Bill of Indictment is signed by the members and returned to the prosecutor or supervising judge. A No Bill is sealed. Mass communications practitioners should note that grand jury investigations and deliberations are totally secret so that only a True Bill of Indictment, which serves as the charge document against defendants in criminal cases, will be filed and made public in court records.

Prosecutor’s Information or Complaint. Although a grand jury indictment is required to bring capital and serious federal criminal charges, that requirement is not imposed on the individual states.4 In many states, a prosecutor may initiate a criminal charge with a document called a “prosecutor’s information” or a “criminal complaint.” The title used for the document depends on the jurisdiction and is set by state constitution or statute. Some states still require all serious felonies to be brought by grand jury indictment, whereas others allow either grand jury indictment or criminal complaint, depending on administrative convenience and the prosecutor’s need for an investigation using the subpoena power of a grand jury.

While the types of charge documents available to a prosecutor depend entirely on the state’s constitution and laws, a prosecutor’s information or criminal complaint routinely requires some form of “probable cause hearing” before an impartial judge. Usually called a preliminary hearing, this judicial procedure allows an unbiased determination by a detached magistrate who listens to a summary of the state’s investigation presented by the prosecutor in the presence of the criminal defendant and his or her attorney. At the conclusion of this hearing, the judge will decide whether or not there is probable cause to believe a crime has been committed and whether the defendant should be held accountable. If the judge decides the defendant should be tried, the defendant is then arraigned on the “prosecutor’s information” or “criminal complaint” and is bound over for trial. There are significant differences between jurisdictions regarding requirement and format for the presentation of evidence at a preliminary hearing. Because of the variations in format and evidence, some of these hearings are presumed open and others are closed to the public. These differences and distinctions made by the U.S. Supreme Court will be discussed in chapter 7 when we address media access to the judicial process.

After an individual is charged with a crime there are still several steps that must be completed prior to trial. The names given these steps and the order in which they are completed may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

First Appearance

One of the first formal hearings in a criminal case is the initial appearance or first appearance. At this hearing, the accused is given a written copy of the charges and the court determines whether the accused can hire a lawyer or will need a court-appointed attorney. If the person is still incarcerated, a second appearance or re-appearance will be scheduled quickly. Between the first and second appearance, the accused is given an opportunity to retain counsel. If the accused is indigent, the court typically appoints counsel at the first appearance. At the second appearance, there will generally be a bond hearing to determine flight and public safety risks posed by the accused and to set or deny bond. If bond had already been set by automatic statutory provision or on the arrest warrant, there may be a bond reduction request by the defendant.

Regardless of how criminal charges were brought, most people accused of crimes are permitted to post bond so they may remain free until their trial.5 For some offenses, bond will be set by statute or the judge may set bond either at a hearing or at the time he or she signs an arrest warrant. Bond either may not be an option or it may be very high, depending on the seriousness of the offense charged and the likelihood the suspect will commit future crimes while released on bond. For cases involving extremely dangerous suspects likely to pose substantial public safety risks, a bond hearing will be set quickly to allow the suspect an opportunity to get an attorney and to permit the prosecutor time to obtain an indictment or further information on the accused.

Arraignment and Plea

The next stage of the criminal process will be for the court to hold an arraignment of the accused. The arraignment is a formal reading of the grand jury indictment or prosecutor’s complaint. An arraignment always includes a discussion by the judge of the sentencing options for each charged crime and a statement of the defendant’s rights in relation to trial. At this time, the defendant is asked to respond with a plea. A plea is the defendant’s formal legal response to the charges. These are entered on the record.

Plea. Pleas generally come in one of three forms: depending on the jurisdiction, the defendant may enter a plea of not guilty, nolo contendere, or guilty. If the defendant enters a plea of not guilty, the criminal justice process continues. If the defendant enters a plea of nolo contendere it means that for this case only, she or he is pleading “no contest” in relation to the charges and the specific facts alleged. A plea of nolo contendere is not an admission of guilt, so it cannot be used against the defendant in any civil case based on the same circumstances. Some states do not permit this plea, but may allow an accused to submit to a stipulated bench trial at which his or her attorney will stipulate on the defendant’s behalf to the facts alleged for the purposes of obtaining a negotiated disposition of the criminal case. This too is not an admission of guilt and will preserve the defendant’s right to contest the facts in any civil suit. If the defendant pleads guilty, a trial is not necessary and the judge moves directly to sentencing or any required presentence investigation.

Plea Negotiations. Many people are amazed to learn that in both federal and state courts 92% to 95% of all criminal convictions result because the defendant pled guilty to obtain a plea bargain.6 A plea bargain is an agreemt made between the prosecutor and a defendant. In such agreements, the defendant pleads or stipulates to the facts of the criminal case and the prosecutor agrees to recommend a specific sentence. Sometimes, this agreement includes the reduction of charges to less serious offenses or the dropping of some charges. The prosecutor is always in command of this situation, and his or her decisions are totally discretionary. It is up to the defendant to decide, based on the advice of his or her attorney, whether to accept the plea bargain or to take a chance with a trial.

Once a defendant accepts a plea bargain, there are several ways this may be presented to the court. Often, the plea agreement is presented at the arraignment stage discussed earlier. Sometimes both sides wait to review evidence before agreeing to a plea bargain. However, it is up to the judge to approve the terms and conditions of the plea bargain and to enter his or her findings on the record. The judge’s findings are based on the nature of the charges, the facts, the defendant’s criminal history, the type of victimization, the danger to the community posed by the defendant, and the usual range of sentences for the crime involved. Media, community, and political pressure also influence judges’ responses to proposed plea bargains. Judges in most jurisdictions automatically accept a prosecutor’s recommended sentence unless some exceptional circumstances are presented by the case. However, in order not to surprise a judge and to avoid unexpected difficulties, foresighted prosecutors and defense attorneys will have had a meeting in chambers with the judge to discuss sentencing recommendations prior to presenting them in open court.

Some judges, as a matter of general practice, and others on special occasion, will mention their own range of routine sentences at the defendant’s arraignment. This is done as an implicit offer to the defendant to plead guilty and save the rigor, expense, and inconvenience of a public trial. Sometimes, there even will be an explicit or implied threat that if the defendant proceeds to trial, the judge would have no trouble imposing the maximum sentence allowable by law, but would be willing to impose a significantly reduced sentence on a plea of guilty.

There are opportunities for plea negotiations much later in the criminal process. In most jurisdictions, the defendant has an option to plead guilty up to the time he or she begins to present a defense at trial. This means it is possible for a defendant to go to trial, wait to see what happens during the testimony and cross-examination of prosecution witnesses, and then make a decision to accept a plea bargain. However, this process depends entirely on the prosecutor’s discretion.

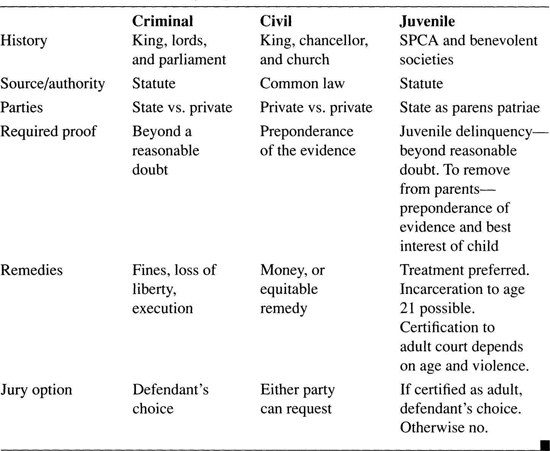

Funnel Effect. Very few crimes actually result in jail sentences for the perpetrators. Out of every 1,000 crimes committed, only 35% are actually reported. Of the crimes reported, 20% are actually cleared by arrest. Of the crimes in which an identified individual is arrested, 50% are not charged by the prosecutor. Of the other 50% who are charged by prosecutors, 30% actually receive full jail sentences. Thus, only about 10 out of every 1,000 criminals are actually apprehended, charged, convicted, and incarcerated as punishment for their crime.7 This funnel effect is shown in Exhibit 2.2.

Exhibit 2.2. Funnel Effect. (See, LAWRENCE BAUM, AMERICAN COURTS: PROCESS AND POLICY 174 [4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1998]; THOMAS R. DYE, UNDERSTANDING PUBLIC POLICY 63−64 [10th ed. Pearson Education, Inc. 2002].)

For every 1,000 crimes committed

Number reported | 350 |

Number arrested | 70 |

Number charged | 35 |

Number sentenced | 10.5 |

Number whose sentence is result of trial conviction | Less than 1 |

Of those criminals actually convicted and sentenced to incarceration, 96% to 99% of their sentences were the result of the plea bargains. So only 2% to 3% of criminal cases actually go to trial. Furthermore, although the federal and many state jurisdictions have mandatory sentencing laws for some crimes, a prosecutor can avoid these by reducing or dismissing charges or by not bringing them in the first place.

Due Process Protections

For the 5% to 8% of criminal defendants who did not elect to avoid trial through a plea, the system grinds on. The defendant was notified of his or her right to trial at the arraignment. Although there may be additional rights given by state constitution to a person accused of a crime, the U.S. Constitution sets out minimum rights.

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.8

In addition to the right to a speedy and public trial before an impartial jury, the defendant also has the right to challenge search and arrest warrants and to ask the court to bar the use of evidence obtained without proper warrant.9 The defendant may also challenge the charge by showing he or she has already been tried for the same actions.10 Furthermore, the defendant is entitled to use the court’s authority to subpoena defense witnesses.11 Many people, including some legislators, law enforcement personnel, prosecutors, and judges, have referred to these constitutional requirements with terms like technicality or loophole. However, they are in place to protect citizens who are falsely accused of crimes and they are, under the U.S. Constitution, the supreme law of the land.12 Exercising all these rights and conducting hearings to ensure the requirements of due process have been met are all part of the pretrial procedure in both federal and state criminal courts.13

Rights of Victims and Accuseds

Often, those who are ignorant of the judicial system and the reasons for due process requirements assert that victims of crimes are left out of the criminal process. In a very real sense those people are right.

Our criminal system recognizes that everyone is victimized when any of us becomes a criminal victim. Therefore, criminal charges are not brought by or on behalf of the individual victim. The prosecution of all crime in our society is done in the name of The People of either the United States or of one of the individual sovereign states. Criminal victims are not parties to criminal procedures. They are merely witnesses on behalf of The People. Our criminal procedures recognize that interests of crime victims are represented by the entire might and weight of the sovereign, which uses its resources to catch, try, and punish those accused of crimes. Our criminal system imposes requirements for due process in order to balance or make fair the trial of someone who must defend him or herself against the power of the sovereign. In short, we try to make the system fair by providing protections and resources to the accused.

It may also help to understand the status of crime victims to note that the U.S. Constitution requires that those accused of crime be treated as innocent until after they are proven guilty. They are not given special rights; people accused, but not yet convicted of crimes, are merely given the same rights as every other citizen, including the alleged victim.14

It is only after a person accused of a crime in our society has been convicted, following all the rules of due process, that he or she becomes a “criminal.” Criminals are legally and constitutionally stripped of all civil rights. Criminals have no right to vote, run for most public offices, keep any licenses they may have acquired, and may lose the right to their life, liberty, or property. The Constitution even says they be made “slaves.” “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”15

Defenses and Motions

In order to protect the due process rights of the accused, the pretrial stages of criminal proceedings must allow him or her to obtain information about the prosecution’s case. He or she must know what witnesses will be called by the prosecution and what their testimony will allege. He or she must also be able to consult with counsel in the formulation of a defense, to make motions concerning the legality of evidence obtained by the state and to obtain defense witnesses. The defendant is also entitled to decide what form of trial will be used.

Discovery. Both the prosecution and defense are required to exchange all their information in the case including witness lists and contact information, and lists of all evidence to be used. Furthermore, the defense must provide the names and addresses of any alibi witnesses and any written or recorded summaries of their potential testimony. All this is done to ensure both sides are able to thoroughly prepare for trial.

Defenses. The defense must tell the prosecutor of any affirmative defenses she or he intends to use at trial. The affirmative defenses allowed by statute in most jurisdictions are infancy, involuntary intoxication, insanity or mental incapacity, or illness and justifiable use of force or self-defense. The first three affirmative defenses arise from common law, where it was understood that some people do not have the capacity to understand the nature or consequences of their actions. Simply put, they do not comprehend what is “right” and what is “wrong.”

The statute that describes each crime will specify a mental state of mind, called under the common law mens rea, as one of the elements the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt in order to convict the defendant. Mens rea elements vary and include frames of mind and connected behavior such as knowingly, recklessly, with wanton disregard for the safety of others, willfully or intentionally. The logic for permitting infancy, involuntary intoxication, or mental incapacity as a defense is the belief that people suffering from those disabilities cannot form the required state of mind.

In some jurisdictions, an alibi may be an affirmative defense. Once a defendant decides to use an affirmative defense, he or she has the burden of proof of that defense by whatever standard has been set by law in the jurisdiction.

The prosecution must prove all of the elements of each crime alleged in the indictment or criminal complaint and must show the defendant committed them beyond a reasonable doubt, but the burden of proof then shifts to the defense to prove any affirmative defenses she or he may have asserted. If the defendant can prove an affirmative defense, the defense bars his or her conviction. The prosecutor must have been given notice of these affirmative defenses so that he or she may prepare to counter them.

Motions. Several pretrial motions are established by statute or court rules. A pretrial motion is a request to the court to either take some action or to order the opposing party to take an action. Pretrial motions may be more easily understood if one simply substitutes the word request