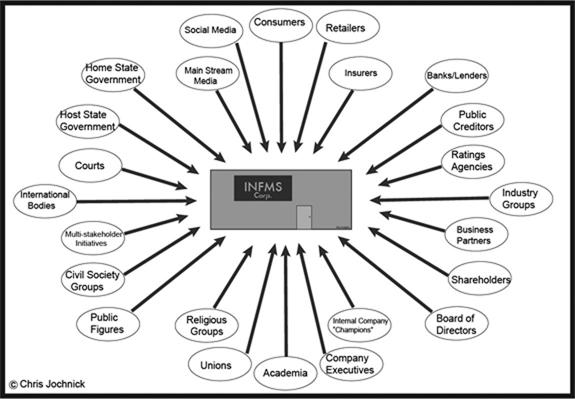

Key constituents that drive the implementation of business and human rights

Chapter 5

Key constituents that drive the implementation of business and human rights

Governments have the primary duty to protect the rights of their own people. The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights1 starts from this premise but also recognizes that in today’s globalized economy, many governments are unable or unwilling to fulfil this obligation. In a world where global companies wield increasing power and influence, the relationship between weak states and powerful companies is increasingly important. When serious human rights issues arise out of commercial activity, the question is: Who will address the governance gap and take responsibility for addressing these human rights challenges? A range of actors is helping to shape and influence this debate. This chapter examines the roles played by civil society organizations, trade unions, consumers and investors.

Chris Jochnick and Louis Bickford examine the role of civil society organizations that are strong advocates for a rights-based perspective. A rights-based approach is founded on the conviction that every person, by virtue of being human, is a holder of rights and that governments have an obligation to respect, promote, protect and fulfil these rights. If governments fail, civil society organizations can empower rights holders to claim their rights. By monitoring corporate operations through their global networks, civil society organizations have the ability to report on company actions, which is an important part of holding them accountable. By participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives, civil society organizations can also contribute to regulating human rights issues in specific industries. By engaging with companies, some civil society advocates also provide guidance and expertise to companies that are seeking to incorporate human rights standards into their business models.

Guido Palazzo, Felicitas Morhart and Judith Schrempf-Stirling explore how consumers are increasingly involved in factoring human rights considerations into their purchasing decisions. In today’s increasingly connected world, dominated as it is by the Internet and social media, consumers, especially younger consumers, have become more sensitive to corporate human rights and environmental issues. Increasingly, they expect global brands to address these issues as a business priority. Palazzo et al., however, highlight the gap between consumers’ intention to purchase responsibly and their actual purchasing decisions. They suggest the need for consumers to focus on their own intrinsic values to break current consumption habits that negatively affect human rights.

The role of investors in advancing the implementation of human rights is a rapidly developing field. An increasing number of investors include ESG data – data that captures the environmental, social and governance aspects of corporations – in their decision-making. Currently, 59 per cent of European assets are in sustainable investments while in the United States (US), US$1 in every US$6 of assets in the US under professional management is invested in a responsible investment strategy.2

Though much of this investor activity focuses on climate change and the environment, the connection between human rights and investments is also coming into sharper focus. Mary Dowell-Jones provides an overview of this developing trend and Mattie J. Bekink examines the need for investors to adopt longer-term investment horizons to allow human rights considerations to take hold.

The global labour movement also plays an essential role in giving workers a voice in the emerging global economy. Empowering workers to organize locally is often the most effective way to ensure that their core rights are protected. Barbara Shailor describes the current state of the international labour movement and considers its future role.

While each of these actors can potentially establish incentives for corporations to make progress on human rights, their success hinges upon the availability of human rights data. Consumers need accessible and comparable human rights data on companies in each industry to make informed purchasing decisions; investors also need to be able to assess the human rights performance of corporations to be able to factor human rights into their investment decision-making. Currently, however, the social dimension of ESG is weakly developed and consumers often have to rely on information from a company’s own website. Civil society organizations and the media are assisting in increasing transparency through reports and projects, yet these efforts rarely enable consumers and investors to systematically compare the human rights performance of companies.3 Developing industry standards and key performance indicators to measure the degree of compliance with particular standards would create comparable data to empower consumers, investors and civil society/labour organizations to differentiate their purchasing, investing and campaigning strategies. The development of such indices will be an important part of the future of business and human rights.

Notes

1. Human Rights Council, ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework’, Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises, UN Doc. A/HRC/17/31 (21 March 2011).

2. US SIF Foundation, Report on US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends (10th ed., 2014) pp. 12–13, www.ussif.org/Files/Publications/SIF_Trends_14.F.E.S.pdf.

3. A notable exception is Oxfam’s ‘Behind the Brands’ project, which assesses the agricultural sourcing policies of the world’s 10 largest food and beverage companies: www.behindthebrands.org.

Section 5.1

The role of civil society in business and human rights

1 Introduction

Civil society organizations (CSOs) play a critical role in promoting and ensuring human rights with respect to companies. The work of CSOs in business and human rights (BHR) has become all the more important in light of the shrinking influence of governments and the growing power of multinational companies. CSOs have flourished in number and influence over the past three decades and are commonly viewed as a third pillar or ‘third force’ alongside the public and private sectors.1 This chapter provides background on the ebb and flow of corporate–civil society engagement; a breakdown of civil society actors; common approaches to corporate advocacy and engagement; and future challenges and opportunities for corporate watchdogs.

2 History of civil society–corporate engagement

Alongside great wealth and progress, corporations have long brought violence, exploitation and protests. Modern civil society debates over BHR echo these original struggles. The abuses of the British and Dutch East India companies provoked church protests and consumer boycotts in 17th-century Britain and 18th-century Massachusetts, and gave rise to the Boston Tea Party. The rise of powerful independent corporations in the late 19th century provoked a wave of bloody worker– company confrontations and led to the modern-day labour movement.2 In the 20th century, corporations were implicated in various anti-colonial struggles and coups in places like Cuba, Haiti, Zaire, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Chile.3

Today’s corporate campaigns are fought over similar issues – exploitation of natural resources, land grabs, abuses of workers and communities and corruption. Organized campaigning by corporate watchdogs emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s. In the United States (US), Cesar Chavez led boycotts against the grape industry, Ralph Nader targeted General Motors and the auto industry and Saul Alinsky launched one of the first shareholder activist campaigns against Eastman Kodak.4 As new technologies and liberalized trade spurred multinational corporate expansion, it also paved the way for North–South collaboration among civil society groups. Early global campaigns were fought over ITT Corporation’s role in the Chilean coup, foreign investments in apartheid South Africa, the use of sweatshop labour by the likes of Nike and Gap, Dow’s production of napalm for use in Vietnam and the horrific chemical explosion killing thousands in Bhopal, India. The apex of these campaigns was reached around the anti-globalization protests in Seattle in 1999, where the full range of activists and corporate targets were on display.5

Despite the evident connection to human rights, the mainstream human rights movement was largely absent from these early corporate campaigns. As a product of Cold War politics, Western funding and liberal ideologies, mainstream human rights groups adopted a narrow vision of human rights that was limited to state actors and largely excluded economic and social rights (the terrain of most corporate abuses).6 It took the high-profile killing of Shell Oil campaigners Ken Saro-Wiwa and others in Nigeria in 1996 to spark significant interest among the likes of Amnesty International (Amnesty) and Human Rights Watch (HRW).7 Early forays into the corporate sphere by these groups focused on the repression of individual activists, rather than the underlying corporate abuses, and BHR never became more than a marginal activity. More robust corporate advocacy instead came from a new wave of Southern-based human rights groups, with closer ties to local communities and social movements, and which were open to challenging the full range of corporate abuses as matters of human rights.

3 Composition of BHR-focused CSOs

The international human rights movement currently comprises hundreds if not thousands of organizations, from small grass-roots civil society groups to large international players.8 These include a visible and influential set of formal and professionalized non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that self-identify as ‘human rights organizations’ and operate at various levels of engagement (international, regional, national) and have different theories of change and strategies.9

3.1 Non-governmental organizations

The story of human rights-based NGOs can be traced back to abolitionist groups acting throughout the world in the 19th century, as well as the international Anti-Slavery Society, founded in Britain in 1839.10 In the 20th century, a global human rights system began to emerge that included national NGOs that worked to document human rights abuses in their home countries, and international NGOs (INGOs) that could operate from the relative safety and security of Northern headquarters, such as New York or London, while partnering with national and regional groups in the global South.11

National NGOs are widely diverse, from small grass-roots or highly localized groups and associations, to better-resourced, more internationally connected organizations that often serve as bridges or ‘translators’ between international institutions and national concerns.12 Importantly, the flow of information, ideas and innovation in the human rights movement has often emerged from these bridge groups.13 Many of these NGOs, including the Kenya Human Rights Commission, SERAC (Nigeria), CDES (Ecuador), Dejustica (Colombia), Aprodeh (Peru), CELS (Argentina), the Democracy Center (Bolivia), Conectas (Brazil) and PODER (Mexico), have developed programming in BHR.

In the early 1990s, following the Vienna Conference,14 a set of human rights-focused INGOs were launched with missions going beyond traditional civil and political rights. These groups, including Global Witness, the Center for Economic and Social Rights and EarthRights International, opened up some of the earliest work on BHR. Companies in extractives industries such as Texaco (operating in the Amazon) and Unocal (operating in Burma) provided the most salient targets for this initial work. More recently, a cohort of INGOs has been established to focus on the information communication and technology (ICT) sector and human rights.15

Within the mainstream human rights movement, arguably the two most influential organizations, Amnesty and HRW, started taking corporations into account only towards the end of the 20th century.16 Amnesty’s early years were characterized by an emphasis on human rights violations committed by states against individuals, including campaigns around prisoners of conscience, stopping torture and ending the death penalty. The Bhopal disaster17 and the killing of Ken Saro-Wiwa forced the organization to address company actors directly. Amnesty established a BHR advisory group in the late 1990s and started researching and campaigning around corporate accountability, including the small arms trade and the extractives industries. Today, Amnesty’s work often targets corporations for human rights abuses.

Consistent with its mission to ‘investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice’, HRW has occasionally touched on themes related to BHR, often through the lens of worker or children’s rights. HRW established a BHR unit in the mid-1990s and has since expanded its work to include reports targeting extractive industries, tobacco companies, corruption, labour conditions in the garment sector and business practices in the US that impact the poor.18

For most NGOs at both the international and national levels the basic operating mode has been to publish hard-hitting investigative reports about the ways in which business practices have violated rights, and to push for more effective government oversight and changes in business behaviour. Other NGOs such as Interights, the Legal Resources Centre (South Africa), the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) and EarthRights International (ERI) have focused on strategic litigation and legal standard-setting to strengthen BHR jurisprudence.

3.2 International networks and movement builders

The International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH, by its French initials), with over 150 members in every world region, self-identifies as a movement builder, facilitating South–South exchange, cross-national strategy and solidarity. By 2009, the FIDH Secretariat in Paris noted that members were increasingly focused on the impacts of economic globalization and the responsibilities of business enterprises. FIDH’s work on BHR has included promoting the recognition of extraterritorial obligations of states; greater corporate accountability; and the rights of victims to remedy and reparation. Other regional or global networks that have developed BHR programming include the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), which convenes lawyers, judges and legal scholars from around the world; the International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR-Net), a membership association of over 200 organizations; and the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-Asia), which has dozens of NGO members throughout Asia.

Movement builders play an important role in providing guidance and disseminating information. The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC),19 established in 2002, has been at the forefront of those efforts, providing original research and analysis, a clearing house of BHR materials and a platform highlighting CSO allegations and responses from companies. Other important players in this respect include the International Corporate Accountability Roundtable (ICAR),20 the Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB),21 Shift22 and the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO),23 all providing important critical resources and guidance around BHR.24

3.3 NGOs outside the mainstream human rights movement

Advocacy around the human rights implications of corporate activity can also be traced to global NGOs not typically associated with the human rights movement. Campaigns by the likes of Greenpeace, Rainforest Action Network, ForestEthics, Friends of the Earth and AmazonWatch have long targeted corporations for both environmental and human rights impacts. These organizations can be credited with some of the most innovative and effective corporate campaigns to date.25 Likewise, humanitarian and development groups like Oxfam, ActionAid and Christian Aid have successfully campaigned against pharmaceutical, mining, oil, agriculture and retail corporations, going back at least as far as the iconic campaign against Nestlé for marketing baby formula, launched in the mid-1970s.26

3.4 Social movements

Throughout history, social movements comprising community groups, indigenous organizations, student groups, workers and unions, the landless, women’s organizations and others have targeted businesses, corporate power and corrupt relationships between businesses and governments. The country-specific acts of a single company like Union Carbide in India, Texaco in Ecuador, Nike in Indonesia, Bechtel in Bolivia, Coca-Cola in Colombia and Vedanta Mining in India, as well as the global operations of companies such as Dow in respect of Agent Orange, Nestlé in relation to infant formula and Monsanto in relation to its use of genetically modified organisms, have been enough to ignite social movement pressure. More often, movements have focused on the complicity of industry leaders with abusive governments (IBM in Nazi Germany, banks and others in apartheid South Africa, ICT companies in Libya and China) or in fomenting conflict (blood diamonds in Angola and conflict minerals in the Democratic Republic of Congo). Anti-globalization movements like the protests against the World Trade Organization in the late 1990s and the more recent Occupy Wall Street movement (and their INGO allies like Public Citizen, Corporate Accountability International and Rights and Accountability in International Development) have focused on trade regimes, the international banking system, multinational corporations (MNCs) and neoliberalism as drivers of injustice. These movements offer powerful opportunities to deploy BHR instruments, but are often weakly informed or sceptical about the United Nations or other multilateral regimes.

3.5 Labour movement

The international labour movement has been fighting BHR issues from its beginning, but almost completely outside the formal human rights realm.27 Potential connections between the labour movement and the human rights movement – for example, around labour conditions, child labour, forced/slave labour, migrant labour, collective bargaining rights and freedom of expression and assembly – have rarely been realized. Until fairly recently, labour rights activists largely ignored international human rights instruments and bodies, and the human rights movement largely ignored worker rights.28 That began to change in the 1990s with the iconic anti-sweatshop campaign against Nike and others.29 Labour and human rights groups joined forces to push Western transnational corporations (TNCs) to account for rights abuses among workers in overseas factories.30 The campaign against Coca-Cola for the killing of union leaders at a local bottling plant in Colombia in the early 2000s demonstrated a growing interest of mainstream human rights groups in threats to labour activists.31 More recently, human rights groups and local labour advocates have brought global attention to worker rights following the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh,32