Introduction to Statutory Framework and Case Law

Fig. 1.1

Externalities associated with food borne illness

1.1.3 History and the Courts’ View of Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C )

The FDA ’s authority over food derives from the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C ). The Act at the center of the FDA’s authority stands at the end of a long history beginning in 1906. Understanding this history is important to gain insight into the drafter’s intent as to what provisions and definitions mean and how the Act should be construed. This is an exercise routinely undertaken by courts .

A Brief Overview of Food Law History

There is a long history of ineffective state regulation in the U.S. prior to 1906. The common law made it a crime to sell diseased meat , for example, as early as 1860. The trouble with the common law approach was two-fold. First, it relied on individuals to bring a suit in law or equity against a seller. There was no State enforcement mechanism to assist in the litigation, thus leaving the full cost and burden of enforcement, including investigations, on private individuals. This proved impractical for the average consumer. Second, the States were powerless when the poison of tainted food poured across State lines. The U.S. was a collection of sovereign States. The private litigant struggled to take their cause of action across State lines. Furthermore, the States relied on the Federal government under its authority to regulate interstate commerce . Absent a Federal statute or Federal agency the interstate sell of food went unregulated.

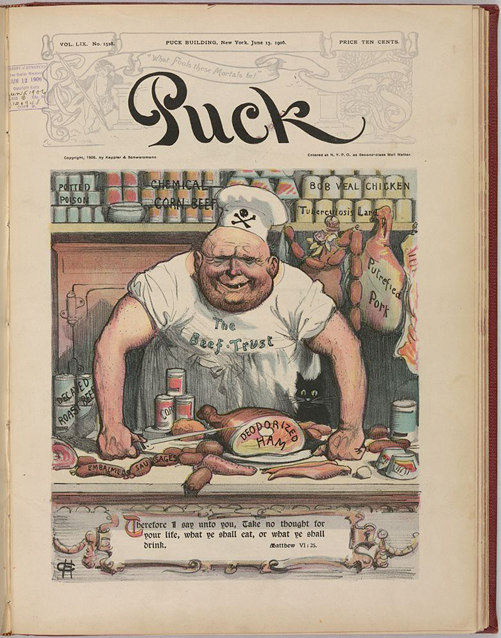

The end of the Civil War and the start of the Industrial Revolution are for many the roots of Federal food safety legislation . Following the Civil War the family farm was largely replaced by the impersonal corporation. Accountability faded and corruption flourished. In the period between 1879 and 1905 over 100 food and drug bills were debated in Congress (FDA Milestones).9 Yet none of them passed. As it so often is, crisis drives change in politics. In this case it was not until the “embalmed beef scandal ” of the Spanish-American War was Congress spurred to action. The scandal is so named because the commander of the Army, General Nelson A. Miles, in testimony to Congress described the beef as having an “odor like an embalmed dead body.” The incident gained widespread media attention with many claiming the tainted meat killed more soldiers than Spanish bullets (See Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2

Political cartoon from the embalmed beef scandal

In 1906, not long after the embalmed beef scandal , Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act . The initial act addressed two issues. It set out to proscribe dangerous foods and drugs and to curtail deceptive marketing and labeling practices. The initial Act was fraught with issues. Chief among the issues was the failure to enact any pre-market testing or review procedures for regulated products.

The 1906 Act persisted for 22 years before another scandal brought change. In 1937 a new cure-all was relased on the market called, “Elixir of Sulfanilamide .” Dissatisfied with the taste, smell, and apperance of the elixir the manufacturer added a combination of chemicals used in paint, varnish, and anti-freeze (FDA Consumer Magazine).10 The toxic effects were never considered and with no FDA pre-market approval process the product simply entered the market. By the time the FDA could take action to remove the product from the market nearly 100 people died. The victims were predominately children. Congress clamoured to act and in 1938 passed the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act . This is still the statute in effect today. The statute which served as the basis for amendments and now the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA ) builds on.

There are three lessons from the passage of the 1938 Act which serve as the tripritie lense through which we must view all Agency actions. These lessons are necessary to also effectively interpret the Act and understand how courts will do the same. These lessons are: (1) the drafter’s indicated court’s should broadly contrue the new Act to protect the public, (2) Congress rejected the 1906 Act’s assumption that consumers were capable of protecting themselves and (3) the objective of the 1938 Act continued to carry the mantale of protecting the public health but also added emphasis to defending consumers by preventing fraud (See Fig. 1.3). We will see the broad construction and deference courts give the Agency and the Act as we discuss nearly every topic. The ignorant consumer standard will be particularly noticeable as we disucuss labeling and restrictions on speech.

Fig. 1.3

Three goals of the 1938 Act

1.1.4 Organization of this Text

It is from this perspective—the personal, the societal, and the historical—we will build our knowledge and understanding of the U.S. food safety laws and enforcement system. We will begin by looking at the post-market surveillance aspects of food law starting with the two largest preliminary issues to any enforcement action . The first issue is determining whether an agency can exercise jurisdiction based on the classification of a regulated product. This issue asks the question, “What is food?” The second is assessing whether an agency conducted a valid inspection within the confines of the U.S. Constitution and the agency’s enabling Acts. In the case where the agency cannot clear these hurdles the other questions about whether the product was harmful or fraudulent are irrelevant.

Chapters 3 and 4 that follow expound on the two principal prohibited acts. Chapter 3 looks at adulteration or the contamination of food, while Chapter 4 looks at misbranding. Misbranding will outline common labeling violations and defenses under the First Amendment. This text will then shift to the pre-market context to explore issues of new ingredients and food packaging under various Amendments. Dietary supplements and other areas of specialized regulation will focus on both pre-market and post-market aspects unique to those products. The text ends with a discussion on private actions for labeling violations and food borne illness and the pinnacle of enforcement—criminal sanctions. Food law and regulation involves nearly facet of food production and this text will touch on each topic, some in greater detail than others.

As an introduction to food law and regulation begin to consider your own relationship with food. How much do you trust the food you buy? Begin by identifying one or two laws or regulations you think may be involved with your favorite food. There are a number of questions you may have about how it is made, marketed, or where it comes from. Some elements you can easily research and find discussions about.

For example, one of my favorite foods is dark chocolate. Did you know the FDA sets a threshold on the amount of insect parts that can be present in chocolate? If a chocolate maker keeps the insects inadvertently collected during harvesting below the threshold the product is deemed safe for consumer. But if the amount passes the threshold it is considered adulterated. This is known as Food Defect Action Levels and it applies to all foods and all types of contaminants.

1.2 Introduction

This chapter begins with the basics of administrative law and regulation. There is a compelling temptation to jump directly into the details of food law and regulation. This urge stems largely from an intuitive sense of what one may expect as a consumer. The regulations , however, are complex making it easy to quickly lose vital context. Rather than begin with a close-up discussion of specific topics, this chapter will take a birds-eye view of administrative law and regulation. From this height the reader can see how all the dots connect and become part of a larger pattern of law and policy.

This chapter starts with an overview of the U.S. legal system. A synopsis of the U.S. legal system offers key insights into the unique separation between the States and Federal government . Understanding this relationship will be important for later topics, such as labeling litigation. It also sheds light on why Federal Agencies are the primary regulators of food identity and safety standards. Other aspects of the U.S. legal system will provide tips on understand judicial opinions and the role of the Constitution in protecting individual liberties.

The chapter then shifts away from the U.S. legal system to narrow its focus on the two primary food product regulators . Beginning with a broad overview of the regulatory landscape the relationship of agencies charged with food regulation and sources of law will come into focus. From this vantage point the reader will have a better sense of where the ensuing chapters fit into the entire food regulatory scheme. For example, jurisdictional boundaries will emerge through key definitions of “food” and “meat.” This introductory material provides the springboard for the remaining chapters on substantive food law.

Food law enjoys a rich complex history. Given the common experience of food some of the concepts will feel intuitive and familiar. Other topics will place new language and boundaries on our expectations as connoisseurs of food. The material in this section aims to plant firm roots that can always be followed when the concept becomes unfamiliar or complicated. Retracing the steps provided in this chapter, from identifying sources of law to understanding key definitions, can act as a guide to grasping the later concepts of this text.

1.3 Overview of the U.S. Legal System

1.3.1 Federalism and the Structure of Government

For readers outside the U.S. it is necessary to take a brief moment to introduce several key concepts of U.S. law and the structure of government . The United States as its name suggests is a union of several sovereign States. Sovereign that is to the extent allowed by the U.S. Constitution . The Constitution is the foundational document both for the creation of a Federal government but also for stipulating how in certain circumstances States govern their citizens. The U.S. Constitution plays three pivotal roles. Absent the Constitution there would be neither Federal agencies nor any Federal laws, like the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act or the FDA . Also without the Constitution there would be no legal grounds for any entity other than a state to regulate food production or safety within its borders. And if never ratified many individual rights and freedoms, like the protection from unreasonable search and seizure, would be missing. The Constitution, therefore, provides a framework for Federal regulation that plays a role in interstate commerce and individual and corporate freedoms and liberties.

The U.S. Constitution establishes a Federal government . Meaning it provides specific powers to the Federal government and the remaining powers to the States. Like a corporate merger the States forfeited rights and reserved others to a new superior organization. This concept is often referred to as Federalism , but can simply be thought of as a vertical division between the Federal government and the States (See Fig. 1.4).

Fig. 1.4

Federalism applied to food law

Federalism places limits on what laws States can enact. Generally speaking the States reserved “police powers,” those powers necessary to protect its citizens’ health and welfare. Still Federal law can enter this zone of State authority using a secondary basis, such as the power to regulate commerce. This is a one way street. Only the Federal government can enact laws where States normally exercise authority. Within certain narrow exceptions States cannot enact laws where Federal law already exists. This is a concept known as preemption . States can enact limited legislation where Federal law exists so long as it does not “unduly burden” interstate commerce . Preemption provides a narrow space for States to regulate. In some instances States, like California, may pass more stringent laws for activities, but the laws will only impact intrastate food production. The more stringent law may be a model for future Federal legislation, but cannot otherwise exercise any effect outsides its borders.

The U.S. Constitution does more than play a role in the relationship between the Federal government and the States. It also provides the primary framework for the laws and structure of the Federal government. From this document the U.S. derives its three branches of government —the legislative , the executive , and the judicial . A term often used around this structure is the “separation of powers ” or “checks and balances .” The essential purpose of the design was to disperse power among several institutions and leaders.

In order to understand the concepts in the chapters to follow it is important to have a basic idea of the role of each branch of government. The legislative branch consists of the bicameral Congress . Congress is comprised of a House of Representatives and a Senate . The U.S. Congress is solely responsible for passing new legislation , such as it did in 1906 with the Pure Food and Drug Act . The executive branch is comprised of the President, Vice President and their administration. In terms of domestic policy, the role of the President is to ensure a duly passed law is implemented and executed. The President organizes the executive branch through a series of Federal agencies that will be responsible for an area of regulation. The two primary food agencies we have today are the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS ). Once a law is passed typically the Agency implementing the law will promulgate a series of rules to provide structure and clarity to vague or broad statutory provisions. The Pure Food and Drug Act , for example, when passed was a mere five pages long! The Federal court system makes up the judicial branch. Federal courts are organized into three layers—district, circuit, and Supreme Court . Nearly every case begins at the district court level and in a series of appeals may be heard by the Supreme Court. Some districts operate with a magistrate judges providing an initial review or decision before the district court. It is the role of the judiciary, the Federal judges across the U.S., to hear challenges to both the statutory provisions and the administrative rules .

1.3.2 The Role of the Constitution in Food Law

The U.S. Constitution not only plays a role in the structure of the Federal government but also constrains the limits of Federal laws. The Constitution enumerates both the limits of Federal power with the States and with individuals. The first ten amendments to the Constitution list the familiar individual freedoms, commonly known as the Bill of Rights . The Bill of Rights includes the freedom of speech , freedom from unreasonable searches , and the protection against self-incrimination among others. If a law infringes on any Constitutional provision it can be challenged, and if successful, the law invalidated. Although Constitutional rights are typically thought of as pertaining solely to individuals, they also apply to corporations. In later chapters we will see First Amendment challenges to advertising and labeling , Fourth Amendment challenges to facility inspections, and Fifth Amendment Due Process challenges when Agencies take enforcement actions.

1.3.3 The Role of Judicial Opinions in Food Law

Introduction to Judicial Opinions

Although regulations play the largest role in this area of law a complete understanding of food law and policy of the U.S. requires an ability to read and interpret judicial opinions. Judicial opinions are the ruling from a judge in a dispute between two parties. The judicial opinion , also known as the ruling, explains the facts of the case, the legal principles involved, and a decision on how the principles apply to the facts at hand. Every judicial opinion follows a formula, which once understood allows the reader to quickly scan and understand the parties involved, the court deciding the case and the basic legal principle in question.

The Structure of Opinions

There are five components to every judicial opinion. All cases begin with the caption. The caption informs the reader who is suing who. If the government brought the suit than the caption will be United States v. Food Processor A and vice versa if industry challenges the government in court. Some cases will name the Agency , for example U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Admin. v. Food Importer X, or the Secretary of the Agency, such as ABC Sugar-Pops Inc. v Sibelius. Below the case caption there are series of letters and numbers called the legal citation. This citation is necessary for any research and retrieval of a particular case. The citation provides the “name of the course that decided the case, the law book in which the opinion was published, and the year in which the court decided the case” (Orin 2007 ).11 There are three levels of judicial review in the U.S., with the U.S. Supreme Court perhaps gaining the most recognition and notoriety. Nearly all lawsuits in Federal court will begin in a district court . Any appeal of a district court ruling will be heard by a Circuit Court of Appeals . If a party wishes to continue its appeal it can request the case be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. The three levels can be quickly distinguished in the citation. U.S. Supreme Court cases using the following citation 712 U.S. 111 while Circuit Court opinions always state the circuit with the year such as, 363 F.2d 465 (6th Cir. 1929). After the legal citation is the judge’s name. If these two are missing from a citation then the opinion is from a district court.

Are All Opinions Treated Equal?

Not all opinions carry the same authority in deciding future cases. Each level of judicial review carries increasing authority. District court opinions are the lowest rung of authority. It will set a new standard only for that district court often acting only as persuasive authority. Circuit courts are binding precedent both on itself and on district courts, but only for those in the same Circuit. There are eleven circuits with three or more States in each Circuit. The Supreme Court as the highest level of review acts as binding authority on all courts. Read opinions with caution. District court opinions should be cited sparingly and Circuit courts cited persuasively outside the Circuit. State court opinions are subject to a similar structure, but names and the nature of appeals will vary by State.

The final two components of a judicial opinion center on the facts and law of the case. The facts of the case are fairly straightforward. The judge will provide a chronological summary of the events that lead to the lawsuit. The only new feature non-lawyers may encounter is the use of “procedural history.” The procedural history explains the path the case took either through the courts , the administrative agency, or both to reach the judge currently deciding the case. For our purposes, it will be important to note the judge’s evaluation of whether the administrative agency finished reviewing the case. In this analysis the judge will conclude whether the case is “ripe for adjudication ” a topic explored in the sections to follow, beginning with Chap. 2. Following the facts the judge will state what legal principles are involved in the case, including any statutory sections , administrative rules , or prior case law, which is known as judicial precedent . The law of the case typically follows two stages. The first stage provides the reader a background of jurisprudence for the topic at hand while the second stage applies the legal principles to the facts of the case (Orin 2007).12 For non-lawyers the most important sections will be the summary of facts and the legal principles. Similar facts will assist in determining whether the principles of the case apply and potentially the outcome as well.

The Impact of Judicial Opinions in Food Law

Judicial opinions play limited roles when interacting with Agencies. It will be the exceptionally rare case that a judicial opinion will play a decisive part in resolving a compliance matter. In court yes, but in the Agency , simply no. Instead, judicial opinions play a role in the background. For example, providing insight into statutory definitions or understanding concepts like Constitutional limits on Agency activities. Judicial opinions play an important role, but only when applied correctly.

1.4 Food Law and Regulation

There are numerous Federal agencies touching food and food safety in some facet. The Government Accountability Office (GAO ) identifies 15 Federal agencies administering no less than 30 laws related to food safety. Some agencies and laws serve only an administrative role, while others stand at the heart of food safety. This section will briefly identify those agencies before concentrating its efforts on the two primary agencies.

1.4.1 Sources of Food Law

There are numerous sources of laws. To make the regulatory landscape more manageable this text will narrow the scope of laws covered. As mentioned above the GAO estimates 30 laws directly involve food topics. From this selection only around five statutes will be discussed. This set of core statutes will cover the most common areas of enforcement and agency approval. A strong understanding of the core statutes serves many valuable purposes. Chief amongst those is understanding the classification of a product. Classification informs many other decisions, such as the controlling agency and the regulatory burden of the product.

Statutes are not the only source of law to consider. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR ) contains the administrative rules issued by various Federal agencies. The rules are organized by Titles, which groups rules by agency or statute. In most cases the CFR title corresponds to the enabling statute. For example, Title 21 covers the rule promulgated to implement and interpret Title 21 of the United States Code , the FD&C Act. Other Titles related to food are Title 7 (agriculture) and Title 9 (animal and animal products). Title 9 contains the bulk of FSIS regulations , whereas Title 7 relates to other USDA activities. When an action is taken by an agency or division of an agency it is important to identify the appropriate statute and regulations associated with that action. Each agency is only responsive to the particular statutes outlining its authority and the regulations providing meaning to that authority.

Sources of Food Law | ||

|---|---|---|

Food Drug and Cosmetic Act | 21 U.S.C. 301 et. seq. | 21 C.F.R. |

Meat Inspection Act | 21 U.S.C. 601 et. seq. | 9 C.F.R. |

Poultry Products Inspection Act | 21 U.S.C. 451 et. seq. | 9 C.F.R. |

Egg Products Inspection Act | 21 U.S.C. 1031 et. seq. | 9 C.F.R |

1.4.2 Primary and Secondary Agencies

In the array of agencies involved in food safety two stand as the megaliths in the center. The FDA and FSIS , the inspection arm of the USDA compose the bulk of Federal funding and staffing of the Federal government ’s food regulatory system. This makes the FDA and FSIS the primary agencies regulating food safety . As will be discussed in detail below, the size of these two agencies matches the massive mandate for each entity.

The Role of Other Agencies and Divisions

Other Federal agencies or divisions of agencies take some minor responsibility for food safety (See Fig. 1.5). These agencies are tertiary to the efforts of the FDA and FSIS . The Department of Homeland Security , for example, is responsible for customs activities which can include coordinating inspections of food imports with the FDA. The USDA ’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS ) also indirectly serves a food safety function. Its programs are aimed to protect plant and animal resources from pests and diseases like bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or “mad cow” disease). The vast array of Federal agencies can be dizzying. The central focus of this text will be on the primary two food agencies tasked with implementing and enforcing food law and regulation.

Fig. 1.5

Food safety roles of the primary and some secondary agencies

An important lesson to understand about Federal agencies is the relationship of divisions within an agency. As outlined above within the FDA and USDA there are divisions or branches within each of the agencies assigned certain product categories or enforcement responsibilities. FSIS and CFSAN were introduced as the primary food divisions with the USDA and FDA respectively. These divisions may be referred to by name or simply by their parent Agency , but no matter how they are called they are never autonomous. They exist within a framework of bureaucracy and regulation which dictates the flow of decision making and the hierarchy for decisions, like appeals.

Introduction to the Food and Drug Administration

The FDA monitors domestic and imported food products. The section below outlines in detail the FDA’s authority and how “food” is defined by its enabling acts. Generally speaking, the FDA regulates all food products except for meat and poultry under the authority of FSIS . This necessarily means, any meat product not regulated by FSIS, such as game meats mentioned below, are under the FDA’s purview. The boundary between FSIS and FDA can be blurry. Eggs are an excellent example. The FDA is responsible for facilities that sell, serve or use eggs as an ingredient. It is also responsible for animal feed but not the laying facilities themselves. FSIS, however, is responsible for liquid, frozen and dried eggs and grading eggs . The primary statutes governing FDA’s activities are the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. 301 et. seq.); the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 201 et. seq.) and the Egg Products Inspection Act (21 U.S.C. 1031 et. seq.).

Only two branches within the FDA take part in food safety and regulation. The Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN ) functions as the central player in food safety for the FDA. It takes on the full range of food safety functions, including (1) food safety research (2) overseeing enforcement (3) evaluating surveillance and compliance programs (4) coordinating with state’s food safety activities, and (5) developing and implementing regulations , guidance documents and consumer safety information (Congressional Research Service).13 The Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM ) straddles the animal-human food connection for the FDA. For food-producing animals the CVM is responsible for ensuring animal feeds and drugs do not produce hazards to humans, in particular with animal drug residues (See Chap. 6 Food Additives). This is in addition to its other functions overseeing pet foods, drugs, and devices.

Introduction to the Food Safety Inspection Service for the U.S. Department of Agriculture

FSIS regulates meat and poultry sold for human consumption. Under the Federal Meat Inspection Act (1906; 21 U.S.C. 601 et seq.) and Poultry Products Inspection Act (1957; 21 U.S.C. 451 et seq.) FSIS inspects the slaughter and processing of animals identified in the statutes. Those animals are defined in detail below. FSIS operates over domestic and foreign meat facilities . FSIS alone is responsible for certifying foreign meat and poultry plants produce products as safety as domestic plants before export to the U.S. FSIS also coordinates with State operated meat and poultry inspection programs. The FMI and the PPI require FSIS to cooperate with State agencies in developing and administering State meat and poultry inspection programs. In its 2013 fiscal year FSIS reported coordinating with 27 States, which oversee 1600 small and very small establishments (FSIS Review).14 FSIS does not inspect the establishment itself. Instead FSIS evaluated each State’s inspection program to ensure it operates on a level “at least equal to” the FSIS inspection programs.

Three additional agencies though not as big or deeply involved as FSIS and FDA offer ancillary services that play a significant role in food safety. Those agencies are the National Marine Fisheries Services (NFMS ), which is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce , the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA ), and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC ), which is also a part of the Department of Health and Human Services . Seafood , with the exception of catfish, falls under the jurisdiction of the FDA. The NFMS, however, conducts a fee-for-service voluntary seafood inspection and grading program for U.S. fish and shellfish. The NFMS’s authority to conduct the voluntary inspections lies in the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 (7 U.S.C. 1621 et. seq.). The EPA well known for clean air and water regulations also regulate chemicals used on food crops . The EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs task is to ensure chemicals used on food crops do not pose a risk to public health . The CDC takes on an investigational role in food borne disease outbreaks and research. It works in concert with the FDA, FSIS, NFMS and state and local health departments to monitor, identify, investigation, and research food borne illnesses. It operates under the authority of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 201 et. seq.).

1.5 What is Food? FDA Jurisdiction and Authority

To achieve its twin aims of protecting the public’s health and its purse the FDA utilizes a quadripartite set of regulations . As the regulations relate to humans, a product is either a drug, device, food /dietary supplement, or a cosmetic. Technically there is a fifth category—none of the above or unregulated by the FDA. This classification decision lies at the heart of every enforcement matter. It also remains the first question before launching a new product or adding a new ingredient. The classification decision is made using the definitions provided in the Act. Failing to start with the definitions is a fundamental mistake.

1.5.1 The Role of Definitions

The definition of food is not what a lay person would think it to be. Asked on the street, “What is food?” One could point to a number of examples—fruit, a bag of chips, or maybe even a sports drink . The definition in the Act, however, is more nuanced. It is a term of art. There are in fact three definitions of food in the Act. Those are provided in the table below.