Illegality and Public Policy

12

Illegality and Public Policy

Contents

12.3 Rationale for the unenforceability of illegal contracts

12.6 Effects of illegality: enforcement

12.7 Effects of illegality: recovery of money or property

12.8 Exceptions to the general rule

12.11 Agreements contrary to public policy

12.12 Contracts concerning marriage

12.13 Contracts promoting sexual immorality

12.14 Contracts to oust the jurisdiction of the courts

12.15 The Human Rights Act 1998

12.16 Contracts in restraint of trade

12.17 Effect of contracts void at common law

This chapter deals with situations where otherwise valid contracts are unenforceable because they are deemed to involve ‘illegality’, or are otherwise contrary to public policy. The following issues are discussed:

The reasons why illegal contracts are unenforceable. ‘Public policy’ is the central issue – but underlying reasons involve ‘deterrence’ and maintaining the integrity of the legal process (that is, not allowing it to be used to enforce illegal arrangements).

The reasons why illegal contracts are unenforceable. ‘Public policy’ is the central issue – but underlying reasons involve ‘deterrence’ and maintaining the integrity of the legal process (that is, not allowing it to be used to enforce illegal arrangements).

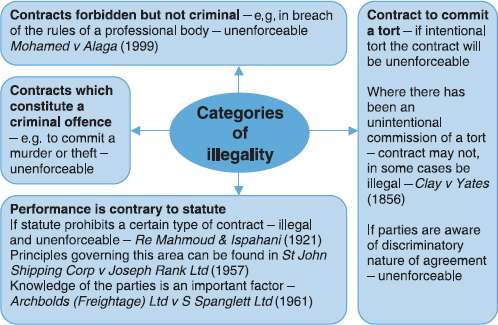

Categories of illegality:

Categories of illegality:

Contracts to commit crimes or torts. These are always illegal.

Contracts to commit crimes or torts. These are always illegal.

Contracts contrary to professional regulations (for example, Solicitors’ Practice Rules). These will not be enforceable, but a party may be able to claim for work actually done.

Contracts contrary to professional regulations (for example, Solicitors’ Practice Rules). These will not be enforceable, but a party may be able to claim for work actually done.

Contracts where performance involves the breach of a statute. This is the most difficult area – the act itself is legal, but the manner of performance is not. The purpose of the statute and the knowledge of the parties will be relevant to the issue of enforceability.

Contracts where performance involves the breach of a statute. This is the most difficult area – the act itself is legal, but the manner of performance is not. The purpose of the statute and the knowledge of the parties will be relevant to the issue of enforceability.

Contracts to indemnify a person for breaking the law. This is not allowed in relation to criminal liability or intentional torts, but is permitted in relation to negligence.

Contracts to indemnify a person for breaking the law. This is not allowed in relation to criminal liability or intentional torts, but is permitted in relation to negligence.

Effects of illegality. Two aspects need consideration:

Effects of illegality. Two aspects need consideration:

Enforcement. Specific performance will not be available, but a legal right related to an illegal transaction may be enforceable if the party does not need to rely on the illegal act to found the claim.

Enforcement. Specific performance will not be available, but a legal right related to an illegal transaction may be enforceable if the party does not need to rely on the illegal act to found the claim.

Recovery of money or property. Generally no recovery is possible, but it may be allowed where:

Recovery of money or property. Generally no recovery is possible, but it may be allowed where:

the illegal purpose has not been carried out – a party is allowed time for a change of mind in relation to the illegal transaction;

the illegal purpose has not been carried out – a party is allowed time for a change of mind in relation to the illegal transaction;

the contract results from ‘oppression’;

the contract results from ‘oppression’;

there is no reliance on the illegal transaction;

there is no reliance on the illegal transaction;

the claimant is a member of the class which the statute concerned is intended to protect.

the claimant is a member of the class which the statute concerned is intended to protect.

Agreements contrary to public policy (but not illegal). In this category fall:

Agreements contrary to public policy (but not illegal). In this category fall:

Contracts related to marriage – for example:

Contracts related to marriage – for example:

for future separation (pre-nuptial agreements are currently caught by this);

for future separation (pre-nuptial agreements are currently caught by this);

imposing a liability if a person marries;

imposing a liability if a person marries;

receiving payment for arranging a marriage.

receiving payment for arranging a marriage.

Contracts promoting sexual immorality. There are old cases supporting this category but it may well be obsolete in the modern law.

Contracts promoting sexual immorality. There are old cases supporting this category but it may well be obsolete in the modern law.

Contracts to oust the jurisdiction of the courts. The parties may agree that matters of fact may be determined by other processes (for example, arbitration) but the courts will always retain a residual jurisdiction over matters of law.

Contracts to oust the jurisdiction of the courts. The parties may agree that matters of fact may be determined by other processes (for example, arbitration) but the courts will always retain a residual jurisdiction over matters of law.

Contracts involving a breach of human rights. It is not clear yet whether the courts will be prepared to treat contracts which conflict with Human Rights Act obligations as unenforceable on public policy grounds.

Contracts involving a breach of human rights. It is not clear yet whether the courts will be prepared to treat contracts which conflict with Human Rights Act obligations as unenforceable on public policy grounds.

Effects of agreements contrary to public policy:

Effects of agreements contrary to public policy:

no specific performance;

no specific performance;

property transferred can probably be recovered.

property transferred can probably be recovered.

Wagering contracts. These have been unenforceable as a result of statutory controls, but the controls have been removed by the Gambling Act 2005. Wagers will now be enforceable.

Wagering contracts. These have been unenforceable as a result of statutory controls, but the controls have been removed by the Gambling Act 2005. Wagers will now be enforceable.

This chapter, like the previous two, is concerned with two situations where the courts will intervene to prevent the enforcement of an agreement which, on its face, has all the characteristics of a binding contract. Both are often put under the general heading of ‘illegality’;1 they might also be grouped as ‘contracts contrary to public policy’.2 There are, therefore, links between these areas. It is felt, however, that they are sufficiently distinct to warrant treatment in separate chapters. There will inevitably be overlaps, and some need to cross-refer, particularly in relation to remedies. The division is simply intended to clarify the discussion of the two areas; it should not be regarded as necessarily reflecting a rigid separation adopted by the courts, or as a denial that there may be significant conceptual links between topics.

The focus in this chapter is on two types of contract. First, it looks at those which are ‘illegal’ in the sense that they involve the commission of a legal wrong – principally, a crime or a tort. This is an area which, even under the classical law of contract, was an accepted limitation on freedom of contract. The second part of the chapter looks at contracts which, while not illegal, are held to be unenforceable because they are for other reasons contrary to public policy.

12.3 IN FOCUS: RATIONALE FOR THE UNENFORCEABILITY OF ILLEGAL CONTRACTS

The reasons why the courts interfere to render contracts which are ‘illegal’ unenforceable, as opposed to simply leaving those who have committed a crime or a tort to the relevant procedures under those areas of law, are not often explicitly stated, other than to say that it is a matter of ‘public policy’. It follows, however, from the fact that ‘public policy’ is the central focus, that the issue of illegality may be raised by the court of its own motion, without it needing to be pleaded by either party.3 The law is not primarily concerned here with the protection of one party, as it is in the areas of duress or undue influence, for example, but with more general concerns of the proper scope of the law of contract and its associated remedies.

Two commentators, Atiyah and Enonchong, have attempted to explore the more specific policies which underlie the law in this area.4 Both suggest that there are two main reasons for the law’s intervention. The first is that of deterrence.5 The law reaffirms the approach taken by the criminal law or tort, and does not allow a person to benefit in any way from ‘illegal’ behaviour.6 As Atiyah points out, the use of unenforceability may be a greater deterrent than the threat of criminal prosecution. In the area of consumer credit, for example, to make a large company liable to relatively small fines for failing to follow correct procedures in dealing with consumers may be less coercive than making the credit contracts unenforceable. This policy does not fully explain, however, why illegal contracts are in some circumstances unenforceable even by innocent parties. A person who does not realise that he or she is infringing the law by the making or performance of a contract cannot be deterred from doing so by making the transaction unenforceable.

A second suggested policy is more general. This is described by Enonchong as protecting ‘the integrity of the judicial system by ensuring that the courts are not seen by law-abiding members of the community to be lending their assistance to claimants who have defied the law’.7 Atiyah calls it ‘the undesirability of jeopardising the dignity of the courts’.8 This means that the courts do not wish to be seen to be involved in the enforcement of transactions with an ‘illegal’ element, since this will bring the legal process into disrepute. This provides more of a justification for refusing to assist even ‘innocent’ claimants in relation to ‘illegal’ contracts. Nevertheless, as Enonchong points out, both of the above reasons for not enforcing illegal contracts can run into conflict with the desirability of preventing injustice to a claimant or a windfall gain by a defendant. He suggests that the law has attempted to ‘steer a middle course’ but that, because it has developed by a process of accretion, there have been conflicts, often unacknowledged, between the above policies. The result of this ‘has been a baffling entanglement of rules which when brought together are, like the common law itself, “more a muddle than a system”’.9

The confusion arises most clearly in relation to the question of the consequences of illegality, to which we shall return at the end of this chapter. For the moment, it is sufficient to note that the dominant reasons for making a contract ‘illegal’ are those of ‘deterrence’ and ‘maintaining the respect of the civil justice system’.10 If the categorisation of a contract as illegal appears to serve neither of these policies, we may legitimately question whether the categorisation is justifiable.

There are two main categories of illegal contract. First, there are those contracts where the agreement itself is forbidden by law (because, for example, it amounts to a criminal offence). Second, there are contracts which become illegal because of the way in which they are performed; generally this arises where the method of performance contravenes a statute. There is a third, subsidiary category of contracts to indemnify a person for the consequences of unlawful behaviour, which will be discussed separately.

12.4.1 CONTRACTS WHICH CONSTITUTE A CRIMINAL OFFENCE

In some circumstances, the making of the contract itself will be a criminal act. The most obvious example is an agreement to commit a crime, such as murder or theft. If A asks B to kill C for a payment of £5,000, and B agrees, then their agreement has all the characteristics of a binding contract in the form of offer, acceptance and consideration. It also amounts to the criminal offence of conspiracy to murder (under the Criminal Law Act 1977), and so will be unenforceable. Any agreement to commit any crime will also be a criminal conspiracy, and treated in the same way. In addition, the Criminal Law Act 1977 preserves the common law offence of ‘conspiracy to defraud’.11 In this case the fraudulent behaviour which is agreed need not amount to a criminal offence.

Figure 12.1

Certain contracts are made illegal by statute. Under the Obscene Publications Act 1959, for example, it is illegal to sell an ‘obscene article’. Here (unlike conspiracy), the offence is only committed by one party (that is, the seller), but nevertheless the contract is illegal and will be unenforceable by either party.

12.4.2 CONTRACTS FORBIDDEN THOUGH NOT CRIMINAL

It has been confirmed in two reported cases that a contract which is forbidden by delegated legislation, in the form of the rules of a professional body, should be treated as an illegal contract, even though the behaviour amounts at most to a disciplinary offence under the rules of that body, rather than being criminal.

Both cases concerned the Solicitors’ Practice Rules 1990, made by the Law Society under s 31 of the Solicitors Act 1974. In the first case, Mohamed v Alaga,12 the defendant solicitor was engaged in asylum work. The claimant was a member of the Somali community who alleged that the defendant had agreed to pay him a share of the solicitor’s fees in return for introducing asylum-seeking clients and assisting in translation work. The sharing of fees was prohibited by the Solicitors’ Rules, and when the claimant sued to recover what he alleged he was owed, he was met by the defence that the agreement, even if made,13 was illegal and unenforceable. This argument was accepted by the Court of Appeal.14

The second case was Awwad v Geraghty & Co.15 In this case the agreement was one whereby the solicitor agreed to act on a ‘conditional fee’ basis. This meant that the solicitor would be entitled to a higher fee if the action was successful. After the action had been settled, the solicitor sent a bill calculated at the lower rate (because the action had been settled, rather than successfully litigated), but the client refused to pay even this amount. When the solicitor sued, the client claimed that the whole agreement was illegal, as being contrary to the Solicitors’ Practice Rules,16 and was therefore unenforceable. The Court of Appeal agreed with this analysis, and held in favour of the client.17

12.4.3 CONTRACT TO COMMIT A TORT

A contract to commit an intentional tort, such as assault or fraud, will be illegal in the same way as a contract to commit a crime.18 On the other hand, it seems that a contract which involves the unintentional commission of a tort will not generally be illegal.19 If, for example, there is a contract for the sale of property which belongs to a third party, but which both the buyer and seller believe to belong to the seller, this will involve the tort of conversion, but the contract itself will not be illegal.20 Where only one party is innocent, it is possible that that party will be allowed to enforce the contract, though the position is uncertain.21 There are dicta in Clay v Yates22 that can be read to suggest that this is the case, but the point was not directly in issue and was not specifically addressed.23

What about a contract which would involve the commission of a ‘statutory tort’ under the Equality Act 2010, in that it would involve unlawful discrimination on grounds of, for example, sex, race or disability?24 It is clear that a requirement to discriminate is itself unenforceable. Thus in Javraj v Hashwani,25 a provision in an agreement that arbitrators were to be appointed from a particular ethnic community was held to be void. But does this affect other obligations under a contract? Suppose, for example, that an employer required an agency supplying temporary staff not to send candidates of a particular sex, racial group, or suffering from a disability? If the agency complied with the employer’s request, would it subsequently be able to claim its fees for supplying the staff? There is no case law directly on such a point,26 but the general principles would suggest that, at least where the parties are aware of the effect of the discriminatory nature of their agreement, it should be unenforceable. Even if the discrimination is unintentional,27 it may well be that the policy of not allowing the legal process to be used in a way that undermines its integrity28 would lead a court to refuse to enforce such an agreement. The situation would probably now be treated as falling within the principles dealing with performance contrary to statute, as discussed in the following section.

12.4.4 PERFORMANCE IS CONTRARY TO STATUTE

Performance which contravenes a statute involves contracts which are prima facie legal, and which are concerned with the achievement of an objective which is legal, but which contravene a statute by the way in which they are performed. Thus, in relation to hire purchase agreements, the Consumer Credit Act 1974 provides that unless various formalities are complied with, the agreement will be unenforceable against the creditor. The aim of the law here is to provide protection for the debtor, and the penalty of unenforceability is used to encourage creditors to make sure that they follow the procedures that Parliament has laid down.29

An example of the application of this approach is to be found in Re Mahmoud and Ispahani.30 The contract was to sell linseed oil. It was a statutory requirement that both seller and buyer should be licensed.31 The seller was licensed, but the buyer was not. The buyer nevertheless told the seller that he was licensed. When the buyer refused to take delivery, the seller sued. It was held that the seller could not enforce the contract because of its illegality, despite its reasonable belief that the defendant was licensed.32 The policy underlying the regulation was to prevent trading in linseed oil other than between those who were licensed, and the innocence of the seller was irrelevant to that policy.

In Hughes v Asset Managers plc,33 by way of contrast, the Court of Appeal upheld share transactions which had been conducted by unlicensed agents. Although the Prevention of Fraud (Investments) Act 1958 imposed sanctions on those who engaged in such trading without a licence, it did not expressly, or by implication, prohibit the making of the contracts themselves. The policy of the Act could be achieved simply by penalising those who traded without a licence.

(1) What could the seller in Mahmoud and Ispahani have done to avoid making an unenforceable contract? (2) What are the practical implications of these two decisions? Is it satisfactory that parties contemplating making a contract need to consider the policy behind any legislation which may govern their transaction?

The principles that should govern this area were considered by Devlin J in St John Shipping Corp v Joseph Rank Ltd.34

Key Case St John Shipping Corp v Joseph Rank Ltd (1957)

Facts: The defendants chartered a ship from the plaintiffs to carry grain between the UK and USA. The ship was overloaded in contravention of the Merchant Shipping Regulations. On arrival in the UK the master was convicted of the overloading offence. The defendants disputed their liability to pay the freight, because the plaintiffs had performed the contract in an illegal manner.

Held: The plaintiffs were entitled to recover. The Merchant Shipping Regulations were not intended to prohibit contracts of carriage as such, even if made in contravention of the regulations.

In reaching this conclusion, Devlin J said it was necessary to ask, first, whether the statute prohibits contracts as such, or only penalises certain behaviour. If the answer to the first question is that it prohibits contracts, does this contract belong to the class which the statute is intended to prohibit?

In answering the first question, he suggested that it was helpful, though not conclusive, to ask whether the object of the statute was to protect the public. If so, then the contract was likely to be illegal. If, on the other hand, the purpose was to protect the revenue (as, for example, in a requirement that those who sell television sets pass the names of the purchasers to the television licensing authority), then it was likely to be legal. This test is difficult to apply, as was shown by the case itself where, despite the fact that the Merchant Shipping Regulations are clearly not designed simply to protect the revenue, the contract was held to be enforceable. It seems to have carried some weight with the Court of Appeal, however, in its decision in Skilton v Sullivan.35 In this case, the plaintiff entered into a contract with the defendant for the sale of koi carp. The defendant paid a deposit. Subsequently, the plaintiff issued an invoice, which described the fish as ‘trout’. The defendant alleged that the plaintiff was trying to avoid paying VAT, since trout were zero-rated and koi carp were not. Thus, he argued, the contract was illegal and could not be enforced against him. The Court of Appeal considered that the plaintiff’s purpose was probably to defer the payment of VAT, rather than to avoid it altogether: nevertheless, this was still an illegal purpose. The court also considered, however, that the plaintiff had formed this dishonest intention after the contract had been entered into. It was therefore not necessary for the plaintiff to rely on his unlawful act in order to establish the defendant’s liability. This was the main basis for the decision, but the court also relied on the principle that illegality which has the object of protecting the revenue is less likely to render a contract unenforceable than where the object is the protection of the public.

12.4.5 RELEVANCE OF KNOWLEDGE

It has been suggested that the knowledge of the parties might be important, so that if both parties know that the contract can only be performed in a way that will involve the breach of the statute, then it will be illegal.

Key Case Archbolds (Freightage) Ltd v S Spanglett Ltd (1961)36

Facts: The case concerned a contract for the carriage of goods. The defendants, who had licences entitling them to carry their own goods on their vans (i.e. ‘C’ licences) agreed to transport a quantity of whisky from London to Leeds for the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs believed that the defendants held ‘A’ licences for their vans, which would have entitled them to carry goods belonging to others. The whisky was stolen on the journey, owing to the negligence of the defendants’ driver. The defendants sought to avoid liability on the basis that the contract was illegal. The plaintiffs succeeded at first instance and the defendants appealed.

Held: The Court of Appeal upheld the first instance decision. There was no evidence that the plaintiffs were aware or should have been aware that the defendants held only C licences. The contract was not prohibited either expressly or impliedly by the relevant statute (the Road and Rail Traffic Act 1933), and was not contrary to public policy. Pearce LJ stated, however, that:37

… if both parties know that though ex facie legal [a contract] can only be performed by illegality, or is intended to be performed illegally, the law will not help the plaintiffs in any way that is a direct or indirect enforcement of rights under the contract.

For Thought

Does this mean that if both parties are aware that a time limit stated as part of a contract of carriage can only be met by a vehicle exceeding the speed limit, the contract will be illegal and unenforceable?

The issue of the knowledge of the parties has been considered further in two recent cases concerned with employment contracts. In Vakante v Addey & Stanhope School38 the applicant was a Croatian national who was seeking asylum in the United Kingdom. He had been in the country since 1992, but was not allowed to work in the UK without permission. He nevertheless obtained a position as a graduate trainee teacher, and was employed for eight months. He was then dismissed. He brought a claim for racial discrimination and victimisation. Mummery LJ noted the test which had been laid down in Hall v Woolston Hall Leisure Ltd,39 in which the Court of Appeal suggested that the proper approach in this sort of case was:

In this case:

(a) [the illegal conduct] was that of Mr Vakante; (b) it was criminal; (c) it went far beyond the manner in which one party performed what was otherwise a lawful employment contract; (d) it went to the basic content of an employment situation; (e) the duty not to discriminate arises from an employment situation which, without a permit, was unlawful from top to bottom and from beginning to end.

The Court of Appeal therefore concluded that the applicant’s complaints were, applying the Hall test, so inextricably bound with the illegality of the relevant conduct that to allow him to recover compensation for discrimination would appear to condone his illegal conduct.

By contrast, the decision in Wheeler v Quality Deep Trading Ltd40 went in favour of the applicant. She was of Thai origin and had limited knowledge of English. She was employed as a cook at a restaurant run by the defendant between November 1999 and January 2003. She was dismissed and brought an application for unfair dismissal. It transpired that she had been being paid without deduction of tax or national insurance. Inaccurate payslips were produced by the employer. The tribunal held that the applicant and her husband, who was well acquainted with the need to pay tax and national insurance and had a good grasp of English, must between them have ‘known something was wrong’ (para 22). It concluded that the employment contract was unlawful. On appeal, the Court of Appeal held that the tribunal had failed to apply the correct test to the situation. It did not properly distinguish between ‘illegality of a contract and illegality in the performance of a legal contract’ (para 26). If, as it seemed, this case fell within the second category, the test to be applied was that set out in Hall v Woolston Hall Leisure. It followed that:

the employment tribunal had to be satisfied that the performance of the contract was illegal, that the employee knew of the facts which made the performance illegal and actively participated in the illegal performance.

Applying this test, the Court of Appeal noted the applicant’s limited English, and the fact that it appeared that her husband had not seen her payslips until shortly before the tribunal hearing, and held that it could not be said that she had actively participated in the illegal performance.

The difference in outcome between these two decisions can be attributed to a significant extent to the court’s view of the knowledge of the parties. In Vakante the applicant knew that he was acting illegally, whereas the employer was innocent; in Wheeler the situation was reversed. Vakante was not allowed to succeed in his claim, whereas Wheeler could.

A test based on the knowledge of the parties is not conclusive, as is shown by Ailion v Spiekermann.41 The contract was for the assignment of a lease, for which a premium was to be paid. This was illegal under the Rent Act 1968, and both parties were aware of this. Nevertheless, the court ordered specific performance of the contract of assignment (though without the illegal premium).42

In Anderson Ltd v Daniel,43 both the issue of the protection of the public and the knowledge of the parties were considered relevant. The contract was for the sale of artificial manure, made up of sweepings of various fertilisers from the holds of ships. Regulations required that the seller should specify the contents of the fertiliser and the proportions of each chemical it contained. This was impractical as far as sweepings were concerned. The Court of Appeal held the contract for sale to be unenforceable by the seller, because the statute was intended to protect purchasers. As Scrutton LJ put it:44

When the policy of the Act in question is to protect the general public or a class of persons by requiring that a contract shall be accompanied by certain formalities or conditions, the contract and its performance without these formalities or conditions is illegal, and cannot be sued upon by the person liable to the penalties.

This seems to suggest that the answer might have been different if the purchaser had sued, rather than the seller.

The overriding questions are, therefore, first, does the statute prohibit contracts? In deciding this, it may be helpful to consider whether it is intended to protect the public, or a class of the public. Second, is this particular contract illegal? Here, it may be relevant to look at the knowledge of the parties, and the guilt or innocence of the party suing.

The second issue inevitably overlaps with the more general issue of the enforceability of illegal contracts, which is considered further below (see 12.6).

The parties may wish to make a type of insurance contract, whereby if one of them commits a crime or tort, the other will pay the amount of any fine or damages imposed, or otherwise provide compensation. Is such an agreement enforceable?

12.5.1 CRIMINAL LIABILITY

It will generally be illegal to attempt to insure against criminal liability.45 There appears to be an exception, however, as regards strict liability offences (that is, where the prosecution does not need to prove any ‘guilty mind’ on the part of the defendant in order to obtain a conviction). Provided the court is satisfied that the defendant is morally innocent, then it seems the contract will be upheld. In Osman v J Ralph Moss Ltd,46 the plaintiff was suing his insurance brokers who had negligently failed to keep him informed that his car insurance was no longer valid (because of the collapse of the insurance company). As a result, the plaintiff had been fined £25 for driving without insurance (an offence of strict, or absolute, liability). The Court of Appeal held that he could recover the amount of the fine from the defendants. Sachs LJ stated that:47

Having examined the authorities as to cases where the person fined was under an absolute liability, it appears that such fine can be recovered in circumstances such as the present as damages unless it is shown that there was on the part of the person fined a degree of mens rea48 or of culpable negligence49 in the matter which resulted in the fine.

The burden of proof was on the defendants to prove circumstances which rendered the fine irrecoverable.

12.5.2 CIVIL LIABILITY

A contract to indemnify will be illegal as regards torts which are committed deliberately, such as deceit, or an intentional libel.50 It is regarded as perfectly acceptable, however, to have such an arrangement as regards the tort of negligence, or where a tort is committed innocently (such as an unintentional libel).51

Where civil liability arises out of a crime, a contract which would provide compensation may be unenforceable. Thus, in Gray v Barr,52 Barr, who had been cleared of manslaughter by the criminal courts, was sued in tort by the widow of his victim. He admitted liability, but claimed that he was covered by his Prudential ‘Hearth and Home’ insurance policy, which covered sums he became liable to pay as damages in respect of injury caused by accidents. The Court of Appeal held (in effect ignoring the verdict in the criminal court) that Barr’s actions did amount to the criminal offence of manslaughter, and that he therefore could not recover under the insurance policy.

A similar refusal to allow reliance on an insurance contract was shown in Geismar v Sun Alliance,53 where the plaintiff was seeking compensation for the loss of goods which had been brought into the country without the required import duty having been paid. There was nothing illegal about the insurance contract itself, which provided standard protection against loss by, among other things, theft. The court held, however, that to allow the plaintiff to recover under the policy in relation to the smuggled goods would be assisting him to derive a profit from a deliberate breach of the law. In arriving at this decision, it was relevant that the failure to pay import duty rendered the goods liable to forfeiture at any time by Customs and Excise, and that the breach was deliberate. It was not suggested that the same approach would be taken in relation to unintentional importation or innocent possession of uncustomed goods.

Different considerations apparently apply, however, where the crime is one of strict liability, or where it arises from negligence. Thus, in Tinline v White Cross Insurance Association Ltd,54 the plaintiff, who had knocked down three people while driving ‘at excessive speed,’ was able to recover from the defendants, his insurers, the compensation he was required to pay to the victims. The exception will not apply, however, if the offence was deliberate.55 The rules in the motoring area are, however, affected by the need to uphold the effectiveness of the system of compulsory insurance, so that the victims, and families of victims, of road accidents receive proper compensation. Thus, in Gardner v Moore, the House of Lords held that even though a car had been driven deliberately so as to cause injury,56 and that therefore the driver would not be able to claim an indemnity under an insurance policy, the statutory provisions contained in the Road Traffic Acts, designed to ensure compensation for the victims of road accidents, allowed the victim to recover compensation directly from the driver’s insurer.57

If a contract is found to be void for illegality, then this will, in general, mean that specific performance will be refused. This is so even if neither party has pleaded illegality.58 The reason is that if there is no contract, the court cannot order it to be performed. It may, however, in some circumstances, be prepared to award damages. This may be done by allowing the action to be framed in tort, as, for example, in Saunders v Edwards,59 where the plaintiff who had been party to an illegal overvaluation of furniture (for the purpose of avoiding stamp duty) in a contract for the sale of a flat was nevertheless allowed to sue for deceit on the basis of the defendant’s fraudulent misrepresentation that the flat included a roof garden. The court took account of the ‘relative moral culpability’ of the two parties, and this question of ‘guilt’ or ‘innocence’ has always been relevant. During the 1980s, it was transformed by a number of decisions into a rather vague test of whether enforcement would offend the ‘public conscience’.60 The House of Lords in Tinsley v Milligan61 rejected this, and reasserted a test based on whether the claimant needs to rely on the illegality to found the claim.

Key Case Tinsley v Milligan (1994)

Facts: In this case, T and M had both supplied the money for the purchase of a house. It was, however, put into the name of T alone in order to facilitate the making by M of false claims to social security payments. When the parties fell out, M claimed a share of the property on the basis of a resulting trust. It was argued for T that M could not succeed because the original arrangement had been entered into in order to further an illegal purpose. The trial judge and the Court of Appeal found for M.