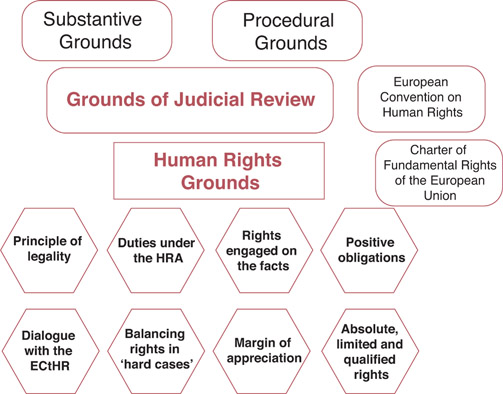

HUMAN RIGHTS GROUNDS FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

16

Human rights grounds for judicial review

16.1 An overview of human rights grounds for judicial review

16.1.1 This chapter has a slightly different structure and style to Chapters 1–15:

- • It begins with the use of ten key cases to explore the workings of human rights-based judicial review.

- • It should be read in conjunction with Chapter 7 (addressing the operation of the European Convention on Human Rights in the United Kingdom, through the Human Rights Act 1998); along with Chapter 13 – which discusses issues of process, standing and remedies in judicial review cases.

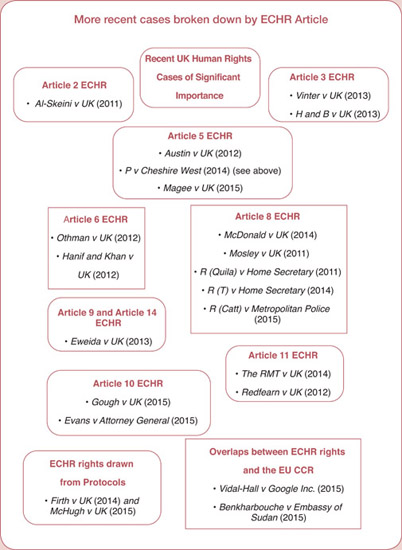

- • The later parts of this chapter focus on and explain how certain human rights-based arguments were used in recent cases involving UK public bodies or the UK Government – broken down by different Articles of the ECHR.

Key human rights principles: Case 1

R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Simms [2000] 2 AC 115

16.1.2 This case features the best exposition of the principle of legality, in the era of human rights law, which has yet been written. In the words of Lord Hoffmann (at 131):

‘Parliamentary sovereignty means that Parliament can, if it chooses, legislate contrary to fundamental principles of human rights. The Human Rights Act 1998 will not detract from this power. The constraints upon its exercise by Parliament are ultimately political, not legal. But the principle of legality means that Parliament must squarely confront what it is doing and accept the political cost. Fundamental rights cannot be overridden by general or ambiguous words. This is because there is too great a risk that the full implications of their unqualified meaning may have passed unnoticed in the democratic process.’

Key human rights principles: Case 2

YL v Birmingham City Council [2007] UKHL 27

16.1.3 The case which still determines the test as to whether duties under human rights law apply (or not) to a private body carrying out a public function – for example, the difference between arranging personal care under a statutory duty (and so human rights duties exist) or carrying out that care under a contract (where human rights duties were found not to exist).

16.1.4 The outcome of the case (in the House of Lords finding there were no human rights duties owed by a privately run care home as a care provider) caused enough political backlash to see the creation of section 145 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 to redress the situation, at least in terms of residential social care.

Key human rights principles: Case 3

R v Horncastle and Others [2009] UKSC 14

16.1.5 At times the UK Supreme Court fronts up to the direction of a line of Strasbourg case law, and holds its own in taking a position eventually followed by the European Court of Human Rights itself. In Horncastle, the rules relating to the admission of ‘hearsay’ evidence in criminal prosecutions for serious crimes, in particularly controversial circumstances (such as when a witness is too intimidated to give evidence), were deemed compatible with the right to a fair trial, as found in Article 6 ECHR.

16.1.6 The Strasbourg Court in time endorsed this ‘municipal’ view of the UK court system on this issue of natural justice – meaning Horncastle is a strong example of the ‘dialogic’ relationship between the European Court of Human Rights and the UK courts.

Key human rights principles: Case 4

In re W (Children) (Family Proceedings: Evidence) [2010] UKSC 12

16.1.7 In notoriously ‘hard’ cases, human rights law in the United Kingdom can be all about balancing the rights of two parties or sides to a dispute, or a criminal case. In W (Children), the right to a fair trial of a defendant was relied upon in the ‘rebalancing’ of that right as against the right to respect for private life of a child complainant in a prosecution for serious sexual offences. Prior to this decision, there had been a presumption that an alleged child victim of a sexual offence would not be cross-examined by defence counsel, but would simply give a statement that would be read to the court in their absence. This presumption was successfully challenged in this case by counsel for a defendant charged with rape of his own stepdaughter.

16.1.8 This ensured that each subsequent application for the prosecution to introduce a statement alone, rather than have such a child complainant cross-examined on the basis of that statement, would need to be examined in the light of the particular facts of the relevant case. This procedural victory of sorts for the right to a fair trial is a morally uneasy one for some, but as Lady Hale reminded us in her judgment in the case: ‘A fair trial is a trial which is fair in the light of the issues which have to be decided.’

16.2 Engaging rights: measuring lawful and unlawful interferences with rights

Key human rights principles: Case 5

P v Cheshire West and Chester Council [2014] UKSC 19

16.2.1 When considering human rights-based grounds for judicial review, first we must be confident that a right protected by the ECHR is ‘engaged’. That is to say, that a right is being negatively affected by the actions or decision of a public body. Tests and analyses of whether a right has been ‘unlawfully interfered with’, or violated, to use the term deployed by the European Court of Human Rights, come as the next stage, once it is established that a Convention right has been engaged by a public body.

16.2.2 In Cheshire West, Lady Hale reminds us that ‘a golden cage is still a cage’. P, the claimant, who is severely disabled, was placed under a care plan by Chester Council staff which meant that his ability to leave his place of residence, a care home known as Z House, was restricted – and he was sometimes restrained while being fed. In this brilliant judgment, which reminds us of how to measure whether human rights of individuals are ‘engaged’, we see that we must measure a human rights infringement, done in a person’s best interests and in good faith, in the same way as with malice or through neglect: hence the phrase, ‘a golden cage is still a cage’.

16.2.3 So a right under the ECHR is still ‘engaged’ if it is interfered with even for a benevolent purpose.

16.3 Absolute, limited and qualified rights in the language of the ECHR

Key human rights principles: Case 6

S and Marper v United Kingdom [2008] ECHR 1581

16.3.1 This case from the European Court of Human Rights shows that the values of the ECHR will not tolerate blanket, inflexible practices that disproportionately affect a (qualified) human right – including the right to respect for private and family life (Article 8 ECHR) in this case. This judgment saw the indefinite retention of DNA profiles on the relevant UK police database deemed to be an unlawful interference with Article 8.

16.4 The concept of ‘positive obligations’ under the ECHR

Key human rights principles: Case 7

Rabone v Pennine Care NHS Trust [2012] UKSC 2

16.4.1 In this case, there was an institutional failing to do enough to prevent the suicide of a person under the care of the National Health Service. Rabone shows us that it is not just the actions of a body with human rights duties that can infringe a person’s rights under the ECHR, but also failures to act, or the disorganisation of such a body and its work which leads to dangerous failures.

16.4.2 As such, Rabone is a case that clearly demonstrates the scope of ‘positive obligations’ placed on public bodies to uphold the rights of individuals under the ECHR.

16.5 The concept of a margin of appreciation

Key human rights principles: Case 8

S.A.S. v France Application No. 43835/11 (1 July 2014)

16.5.1 When Governments interfere with a qualified right under the ECHR, through the creation of a criminal offence in their domestic law, they may do so with greater latitude using their ‘margin of appreciation’ – meaning that the legal and constitutional culture and conventions of that jurisdiction may make for greater possible restrictions on the scope of some rights than in other jurisdictions across the Council of Europe.

16.5.2 In this case, the so-called ‘burqa ban’ was upheld by the Strasbourg Court as being within the French Government’s ‘margin of appreciation’, largely due to the French secular constitutional value of ‘laïcité’.

Key human rights principles: Case 9

Hirst v United Kingdom (No. 2) [2005] ECHR 681

16.5.3 But the notion of a Government’s ‘margin of appreciation’ only runs so far. In Hirst, the European Court of Human Rights determined that it was unlawful, as a blanket and inflexible ban, to prevent all prisoners in the United Kingdom from voting in any elections at all while they were serving their sentences – of any length, that is, and in relation to offences of all severities.

16.5.4 The judgment in this case has been repeated by the European Court of Human Rights in several others since, leading to David Cameron, UK Prime Minister, claiming that it makes him feel ‘physically ill’ to contemplate allowing any prisoners to vote.

16.6 Preventing the use of ECHR rights to undermine the rights of others

Key Human Rights Principles: Case 10

Norwood v UK [2005] 40 EHRR SE11 (Application No. 23131/03)

16.6.1 Norwood had displayed an offensively anti-Islamic poster in the window of his property, and was duly convicted of a public order offence. He tried to challenge his conviction before the European Court of Human Rights on the basis that the relevant criminal conviction unlawfully restricted his freedom of expression – but his claim was deemed inadmissible and it therefore failed.

16.6.2 The Strasbourg Court (and the ECHR) cannot tolerate the purported use of a qualified right (freedom of expression) to undermine the rights, safety and well-being of others in society.

16.6.3 The principle that legal arguments based on human rights in the ECHR cannot be used to undermine the rights of others is laid down in Article 17 ECHR.

16.7 Article 2 ECHR

16.7.1 Article 2 ECHR provides individuals with the right to life, which also entails a positive obligation for deaths to be investigated by the Member State which should have safeguarded the lives of individuals that are killed.

16.8 Article 3 ECHR

16.8.1 Article 3 ECHR protects individuals from torture, as well as inhuman or degrading treatment. This protection must be extended to even the most reviled or hateful criminal offenders in a society; or as Sir Tom Bingham once noted, those subject to the greatest ‘public obloquy’, or stigmatisation. It must also be a right extended and used to protect the most vulnerable in society, such as failed asylum seekers unable to return safely to their country of origin.

16.8.2 Vinter v United Kingdom 34 BHRC 605 (ECtHR)

Key Facts

Key Facts

In Vinter, the applicants successfully challenged the ‘whole life tariffs’ which were their punishments for extremely serious crimes, including murder. It was held by the European Court of Human Rights that a ‘whole life tariff’ of imprisonment, which meant a prisoner could only be released by the order of the Home Secretary, and then on compassionate grounds, was unlawful; it was tantamount to inhuman or degrading treatment, since there was no guarantee at any point in the future of a review of the appropriateness of the imprisonment of an individual, thus engaging Article 3 ECHR.

Key Law

Key Law

It should be an important premise in the criminal justice system of a Council of Europe Member State, such as the United Kingdom, that however horrendous or outrageous a crime committed by an individual, the function of the imprisonment of that person should also be rehabilitation as well as punishment, or the safeguarding of the public. An automatic review of the imprisonment of a purported ‘lifer’ ensured that there was some prospect of release; and enough reason to warrant their personal engagement with a programme of ‘rehabilitation work’ while in prison.

16.8.3 H and B v United Kingdom (2013) 57 EHRR 17 (ECtHR)

Key Facts

Key Facts

H and B were failed asylum seekers, originally living in Afghanistan, who had worked for the US and UN administrations in their home country, and so were, they felt, targets for Taliban or anti-Western extremists if they were to be returned by the UK Government to Afghanistan. In this case, the European Court of Human Rights dismissed their claim that their forcible return to Afghanistan by the UK Government would constitute a breach of their Article 3 ECHR rights.

Key Law

Key Law

It was determined by the European Court of Human Rights in this case that it was for the claimants in such circumstances to establish that there was no ability on their part to avoid persecution upon their return, and that there were substantial grounds to believe that they would be subject to torture, or inhuman or degrading treatment upon their return to Afghanistan; which H and B failed to do. Cases such as that of H and B will often be decided on the very specific evidence of risk in that particular case.

16.9 Article 5 ECHR

16.9.1 Article 5 ECHR protects the right to liberty and security of the person – and is ‘engaged’ or affected, in many different sorts of contexts where an individual is bodily or spatially controlled or restrained. In P v Cheshire West (2014), discussed in this chapter, above, the UK Supreme Court drew on a great deal of case law from the European Court of Human Rights to determine that the first issue in examining whether there had been an infringement of Article 5 ECHR is to establish the degree to which a person’s liberty was actually limited or restricted, even if this was done in their best interests, in the context concerned.

16.9.2 Austin v UK (2012) 55 EHRR 14 (ECtHR)

Key Facts

Key Facts

Thousands of demonstrators had been detained within box-shaped police cordons on the streets of London (a police tactic often called ‘kettling’), after some of the demonstrators had become more violent and disorderly in their behaviour. Austin had been one of the demonstrators that were ‘kettled’ for more than five (and up to seven) hours in cold, open streets with no shelter, water or food provided, while the police dispersed the crowd gradually through an opening in one part of their cordon. Austin claimed that the police tactics had been a breach of her Article 5 ECHR rights. The European Court of Human Rights dismissed her claim.

Key Facts

Key Facts Key Law

Key Law