Frustration

13

Frustration

Contents

13.4 Limitations on the doctrine

13.5 Effects of frustration: common law

13.6 Effects of frustration: the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943

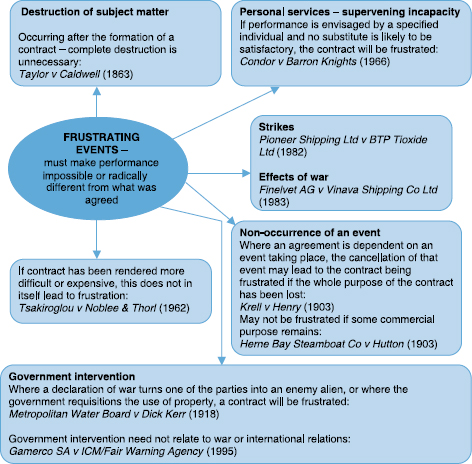

The doctrine of frustration deals with the situation where circumstances change after a contract has been made, and this makes the performance impossible, or at least significantly different from what was intended. The following aspects need discussion:

The nature of the doctrine. Is the doctrine based on an implied term in the contract, or simply on a rule of law?

The nature of the doctrine. Is the doctrine based on an implied term in the contract, or simply on a rule of law?

What sort of events will lead to the frustration of a contract? Examples include:

What sort of events will lead to the frustration of a contract? Examples include:

destruction of the subject matter – this is the clearest example of frustration;

destruction of the subject matter – this is the clearest example of frustration;

where personal performance is important, the illness of one party may frustrate the agreement;

where personal performance is important, the illness of one party may frustrate the agreement;

where the contract presumes the occurrence of an event, its cancellation may be treated as frustration;

where the contract presumes the occurrence of an event, its cancellation may be treated as frustration;

if the contract becomes illegal, or a government intervenes to prohibit it.

if the contract becomes illegal, or a government intervenes to prohibit it.

Limitations on the doctrine. It will not apply where:

Limitations on the doctrine. It will not apply where:

the contract simply becomes more difficult or expensive to perform;

the contract simply becomes more difficult or expensive to perform;

the ‘frustration’ is attributable to the actions of one of the parties;

the ‘frustration’ is attributable to the actions of one of the parties;

the parties have provided for the circumstances in the contract itself.

the parties have provided for the circumstances in the contract itself.

Effects of the doctrine under the common law:

Effects of the doctrine under the common law:

the contract is terminated automatically; but

the contract is terminated automatically; but

all rights and liabilities which have already arisen remain in force; except that

all rights and liabilities which have already arisen remain in force; except that

if there is a total failure of consideration, money paid may be recovered.

if there is a total failure of consideration, money paid may be recovered.

The Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. This Act amends the common law, so that:

The Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. This Act amends the common law, so that:

money paid prior to frustration can generally be recovered;

money paid prior to frustration can generally be recovered;

benefits conferred, which survive the frustrating event, can be compensated for.

benefits conferred, which survive the frustrating event, can be compensated for.

This topic, the doctrine of frustration, has links with preceding chapters, and with the one that follows. Frustration can, from one point of view, be looked at as something that vitiates a contract, and in particular has similarities with the area of ‘common mistake’.2 Whereas, vitiating factors generally relate to things which have happened, or states of affairs which exist, at or before the time when the contract is made, frustration deals with events which occur subsequent to the contract coming into existence. Since frustration has the characteristics of an event which discharges parties from their obligations under a contract, it also has links with the topics of performance and breach (see Chapter 14).

The situation with which the doctrine of frustration is concerned is where a contract, as a result of some event outside the control of the parties, becomes impossible to perform, at least in the way originally intended. What are the rights and liabilities of the parties?

13.2.1 ORIGINAL RULE

In Paradine v Jane,3 the court took the line that obligations were not discharged by a ‘frustrating’ event, and that a party who failed to perform as a result of such an event would still be in breach of contract. The justification for this harsh approach was that the parties could, if they wished, have provided for the eventuality within the contract itself.4 In commercial contracts this is in fact often done, and force majeure clauses are included so as to make clear where losses will fall on the occurrence of events which affect some fundamental aspect of the contract.5 Disputes about whether a contract is frustrated are therefore less common in the commercial context than those about the interpretation of a force majeure clause.6

13.2.2 SUBSEQUENT MITIGATION

The Paradine v Jane approach, however, proved to be too strict and potentially unjust, even for the nineteenth-century courts, which were in many respects strong supporters of the concept of ‘freedom of contract’, taking the view that it was not for the court to interfere to remedy perceived injustice resulting from a freely negotiated bargain. The modern law has developed from the decision in Taylor v Caldwell.7

Key Case Taylor v Caldwell (1863)

Held: It was held that since performance was impossible, this event excused the parties from any further obligations under the contract. Blackburn J justified this approach on the basis that where the parties must have known from the beginning that the contract was dependent on the continued existence of a particular thing, the contract must be construed:8

… as subject to an implied condition that the parties shall be excused in case, before breach, performance becomes impossible from the perishing of the thing without the fault of the contractor.

The doctrine at this stage, then, is based on the existence of an implied term. This enabled the decision to be squared with the prevailing approach to freedom of contract, and was adopted in subsequent cases.9 It also tied in with classical theory that all is dependent on what the parties intended at the time of the contract.10 In reality, of course, this is something of a fiction.11 Some judges in more recent cases have recognised this. In particular, Lord Radcliffe in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham UDC,12 in a passage that has often been quoted subsequently, stated that, in relation to the implied term theory:

… there is something of a logical difficulty in seeing how the parties could even impliedly have provided for something which, ex hypothesi, they neither expected nor foresaw; and the ascription of frustration to an implied term of the contract has been criticised as obscuring the true action of the court which consists in applying an objective rule of the law of contract to the contractual obligation which the parties have imposed on themselves.

In truth, however, the problem with the implied term theory is not one of logic. Although the parties may not have foreseen the particular event,13 there is nothing illogical about agreeing that, in general terms, unforeseen events affecting the nature of the parties’ obligations will result in specified consequences. Indeed, most force majeure clauses will include a provision to this effect. And if this can be done by an express clause, there is no reason why it cannot be done by one which is implied.

The real objection to the implied term theory here, as elsewhere in the law of contract,14 is that it obscures what the courts are actually doing – which is, in this case, deciding that certain events have such an effect on the contract that it is unfair to hold the parties to it in the absence of fault on either side, and in the absence of any clear assumption of the relevant risk by either party. That this is the basis for intervention has been recognised by some judges. In Hirji Mulji v Cheong Yue Steamship Co Ltd,15 for example, Lord Sumner commented that the doctrine ‘is really a device by which the rules as to absolute contracts are reconciled with a special exception which justice demands’. This line has been supported by Lord Wright both judicially in Denny, Mott and Dickson Ltd v James Fraser16 and, more explicitly, extra-judicially.17 It thus forms one of the two other main theoretical bases, as alternatives to the implied term, put forward as explanations of the doctrine of frustration.18 It is by no means universally accepted, however, perhaps because of its uncertainty, and the third theory, based on ‘construction’, seems to be the one that is currently favoured.19 The most frequently cited statement of this theory is that of Lord Radcliffe in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham UDC.20 Having outlined the artificiality of the implied term approach, he commented:

So perhaps it would be simpler to say at the outset that frustration occurs whenever the law recognises that without default of either party a contractual obligation has become incapable of being performed because the circumstance in which performance is called for would render it a thing radically different from that which was undertaken by the contract. Non haec in foedera veni. It was not this that I promised to do.

The approach is, therefore, to ask what the original contract required of the parties,21 and then to decide, in the light of the alleged ‘frustrating’ event, whether the performance of those obligations would now be something ‘radically different’. This has been subsequently endorsed as the best approach by the House of Lords in National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd.22

The operation of this approach requires the courts to decide what situations will make performance ‘radically different’ – and it is to this issue that we now turn.

It is clear that ‘radical difference’ will include, but is not limited to, situations where performance has become ‘impossible’. Unfortunately, neither ‘impossibility’ nor ‘radical difference’ has a self-evident meaning in this context. Both require interpretation in their application. There is, however, guidance to be obtained from looking at the cases. Although the categories can never be closed, it is possible to identify certain occurrences that have been recognised by the courts as amounting to frustration of the contract.

13.3.1 DESTRUCTION OF THE SUBJECT MATTER

In the same way that the destruction of the subject matter prior to the formation of a contract will render it void for common mistake,23 destruction at a later stage will fall within the doctrine of frustration, as indicated by Taylor v Caldwell.24 Complete destruction is not necessary. In Taylor v Caldwell itself, the contract related to the use of the hall and gardens, but it was only the hall which was destroyed.25 The contract nevertheless became impossible as regards a major element (use of the hall), and was therefore frustrated. In other words, if what is destroyed is fundamental to the performance of the obligations under the contract, then the doctrine will operate.26

Figure 13.1

It seems that complete physical destruction may not be necessary if the subject matter has been affected in a way which renders it useless. In Asfar v Blundell,27 for example, a cargo of dates was being carried on a boat which sank in the Thames. The cargo was recovered, but the dates were found to be in a state of fermentation and contaminated with sewage. The judge found that they ‘had been so deteriorated that they had become something which was not merchantable as dates’.28 On that basis, there was a total loss of the dates, and the contract was frustrated.

13.3.2 PERSONAL SERVICES – SUPERVENING INCAPACITY

If a contract envisages performance by a particular individual, as in a contract to paint a portrait, and no substitute is likely to be satisfactory, then the contract will generally be frustrated by the incapacity of the person concerned.

Key Case Condor v Barron Knights (1966)29

Facts: The drummer with a pop group was taken ill. Medical opinion was that he would only be fit to work three or four nights a week, whereas the group had engagements for seven nights a week.

Held: His contract of employment was discharged by frustration. He was incapable of performing his contract in the way intended.

In many cases, of course, the identity of the person who is to perform the contract will not be significant. Suppose, for example, a garage agrees to service a car on a particular day, but on that day, as a result of illness, it is short-staffed and cannot carry out the service. This will be treated as a breach of contract, rather than frustration. The contract is simply to carry out the service, and the car owner is unlikely to be concerned about the identity of the particular individual who performs the contract, so long as he or she is competent.30

For Thought

Do you think the position would be the same if there were a flu epidemic, and the garage had no mechanics available at all?

13.3.3 NON-OCCURRENCE OF AN EVENT

If the parties reach an agreement which is dependent on a particular event taking place, the cancellation of that event may well lead to the contract being frustrated. This situation arose in relation to a number of contracts surrounding the coronation of Edward VII, which was postponed owing to the king’s illness.

Key Case Krell v Henry (1903)31

Facts: The defendant had made a contract for the use of certain rooms in Pall Mall owned by the plaintiff for the purpose of watching the coronation procession. He paid a deposit of £25 and was to pay the balance of £50 on the day before the coronation. Before this day arrived, the king was taken ill, and the procession postponed. The plaintiff sued for the payment of the £50, and the defendant counter-claimed for the return of the £25 (though this claim was later dropped).

Held: The Court of Appeal held that the postponement of the procession frustrated the contract. Although literal performance was possible, in that the room could have been made available to the defendant at the appropriate time, and the defendant could have sat in it and looked out of the window, in the absence of the procession it had no point, and the whole purpose of the contract had vanished. The decision of the trial judge in favour of the defendant was upheld.

By contrast in another ‘coronation case’, Herne Bay Steamboat Co v Hutton,32 the contract was not frustrated. Here, the contract was that the plaintiff’s boat should be ‘at the disposal of’ the defendant on 25 June to take passengers from Herne Bay for the purpose of watching the naval review, which the king was to conduct, and for a day’s cruise round the fleet. The king’s illness led to the review being cancelled. In this case, however, the Court of Appeal held that the contract was not frustrated. The distinction from Krell v Henry is generally explained on the basis that the contract in Herne Bay was still regarded as having some purpose. The fleet was still in place (as Stirling LJ pointed out), and so the tour of it could go ahead, even if the review by the king had been cancelled. The effect on the contract was not sufficiently fundamental to lead to it being regarded as frustrated.

13.3.4 IN FOCUS: ANOTHER INTERPRETATION OF HERNE BAY V HUTTON

Brownsword has taken a different view of the Herne Bay case. He has argued that the contract would not have been frustrated even if the fleet had sailed away.33 In his view the distinction between the cases is that Hutton, the hirer of the boat, was engaged in a purely commercial enterprise, intending to make money out of carrying passengers around the bay, whereas Henry was in effect a ‘consumer’, whose only interest was in getting a good view of the coronation procession. This approach also emphasises that it is important to determine exactly what the parties had agreed. As Vaughan Williams LJ suggested in Krell v Henry,34 if there was a contract to hire a taxi to take a person to Epsom on Derby Day, and the Derby was subsequently cancelled, this would not affect the contract for the hire of the taxi; the hirer would be entitled to be driven to Epsom, but would also be liable for the fare if he chose not to go.

13.3.5 GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION

If a contract is made, and there is then a declaration of war which turns one of the parties into an enemy alien, then the contract will be frustrated.35 Similarly, the requisitioning of property for use by the government can have a similar effect, as in Metropolitan Water Board v Dick Kerr.36 In this case, a contract for the construction of a reservoir was frustrated by an order by the Minister of Munitions, during the First World War, that the defendant should cease work, and disperse and sell the plant.

Here, as is the case in relation to the non-occurrence of an event, it must be clear that the interference radically or fundamentally alters the contract. In FA Tamplin v Anglo-Mexican Petroleum,37 a ship which was subject to a five-year charter was requisitioned for use as a troopship. It was held by the House of Lords that the charter was not frustrated, since judging it at the time of the requisition, the interference was not sufficiently serious.38 There might have been many months during which the ship would have been available for commercial purposes before the expiry of the contract.

Similarly, the fact that the contract has been rendered more difficult, or more expensive, does not frustrate it.

Key Case Tsakiroglou & Co v Noblee and Thorl (1962)39

Facts: The appellants agreed to sell groundnuts to the respondents to be shipped from Port Sudan to Hamburg. Both parties expected that the shipment would be made via the Suez Canal, but this was not specified in the contract. The Suez Canal was closed by the Egyptian government, and this meant that the goods would have had to be shipped via the Cape of Good Hope, extending the time for delivery by about four weeks. The appellants failed to ship the goods and the respondents sued for non-performance. The appellants argued that the contract had been frustrated.

Held: The House of Lords held that this was not frustration. The route for shipment had not been specified in the contract, nor was any precise delivery date agreed. The fact that the rerouting would cost more was regarded as irrelevant. The appellants were in breach of contract and the respondents entitled to succeed in their action.

The government intervention need not relate to war or international relations. In Gamerco SA v ICM/Fair Warning Agency,40 the Spanish government’s closure of a stadium for safety reasons was held to frustrate a contract to hold a pop concert there.

An unsuccessful attempt was made in Amalgamated Investment and Property Co Ltd v John Walker & Sons41 to base frustration on a different type of government interference, namely the ‘listing’ of a building as being of architectural and historic interest, and therefore subject to strict planning conditions. Despite the fact that this was estimated as having the effect of reducing the market value of the building to £200,000 (the contract price was £1,700,000), the Court of Appeal held that the contract was not frustrated. It was not part of the contract that the building should not be listed, and the change in the market value of the property could not in itself amount to frustration. The decision presumably leaves open the possibility that if the non-listing of a building was stated as being a crucial element in the contract, then frustration could follow from such a listing.

Such an outcome is perhaps less likely in the light of the Court of Appeal’s later decision in the case of Bormarin AB v IMB Investments Ltd.42 In this case, a contract for the purchase of the share capital of two companies had been set up with the main purpose of enabling the buyer to be able to set off losses against gains, as was at that time allowed by tax law. Subsequently, the law changed, so that such losses could no longer be set off. The seller sought to enforce the agreement but, at first instance, it was held that the contract had been frustrated by the change in the law. On appeal, however, the Court of Appeal ruled that frustration could not be used where, as a result of a change in the law, a bargain turned out to be less advantageous than had been hoped.

13.3.6 SUPERVENING ILLEGALITY

If, after a contract has been made, its purpose becomes illegal, this will be regarded as a frustrating event. In Denny, Mott and Dickson v James Fraser,43 there was an agreement for the sale of timber over a number of years. It provided that the buyer should let a timber yard to the seller, and give him an option to purchase it. In 1939, further dealings in timber were made illegal. The House of Lords held that not only the trading contract, but also the option on the timber yard, was frustrated. The main object of the contract was trading in timber and, once this was frustrated, the whole agreement was radically altered.

13.3.7 OTHER FRUSTRATING EVENTS

Other types of event which have been held to lead to frustration include industrial action, particularly if in the form of a strike, and the effects of war. For example, in Pioneer Shipping Ltd v BTP Tioxide Ltd,44 the House of Lords upheld an arbitrator’s view that a time charter was frustrated when strikes meant that only two out of the anticipated six or seven voyages would be able to be made. As regards the effects of war, in Finelvet AG v Vinava Shipping Co Ltd,45 a time-chartered ship was trapped by the continuing Gulf War between Iran and Iraq. Again, the court upheld the view of an arbitrator that this was sufficiently serious to mean that the contract was frustrated.

The general limitations on the availability of a plea of frustration, in terms of the seriousness of the event and its effect on what the parties have agreed, have been discussed above. In this section, three more specific limitations are noted.

13.4.1 SELF-INDUCED FRUSTRATION

If it is the behaviour of one of the parties that, while not necessarily in itself amounting to a breach of contract, has brought about the circumstances which are alleged to frustrate the contract, this will be regarded as ‘self-induced frustration’, and the contract will not be discharged. For example, if the fire which caused the destruction of the music hall in Taylor v Caldwell46 had been the result of negligence by one of the parties, the contract would not have been frustrated. This is an obvious restriction, but it may not always be easy to determine the type of behaviour that should fall within its scope. An example of its application is Maritime National Fish Ltd v Ocean Trawlers Ltd.47 The appellants chartered a trawler from the respondents. The trawler was fitted with an ‘otter’ trawl, which it was illegal to use without a licence, as both parties were aware. The appellants applied for five licences to operate otter trawls, but were only granted three. They decided to use these for boats other than the one chartered from the respondents. They claimed that this contract was therefore frustrated, since the trawler could not legally be used. The Privy Council held that the appellants were not discharged. It was their own election to use the licences with the other boats which had led to the illegality of using the respondants’ trawler.

This decision seems fair where it is the case, as it was here, that the party exercising the choice could have done so without breaking any contract (since the trawlers to which the licences were assigned all belonged to the appellants).48 It may not be so fair, however, if

Frustration a person is put in a position where there is no choice but to break one of two contracts. Nevertheless, when this situation arose in Lauritzen (J) AS v Wijsmuller BV, The Super Servant Two,49 the Court of Appeal applied the concept of self-induced frustration strictly.

Key Case Lauritzen (J) AS v Wijsmuller BV, The Super Servant Two (1990)