Freehold Covenants

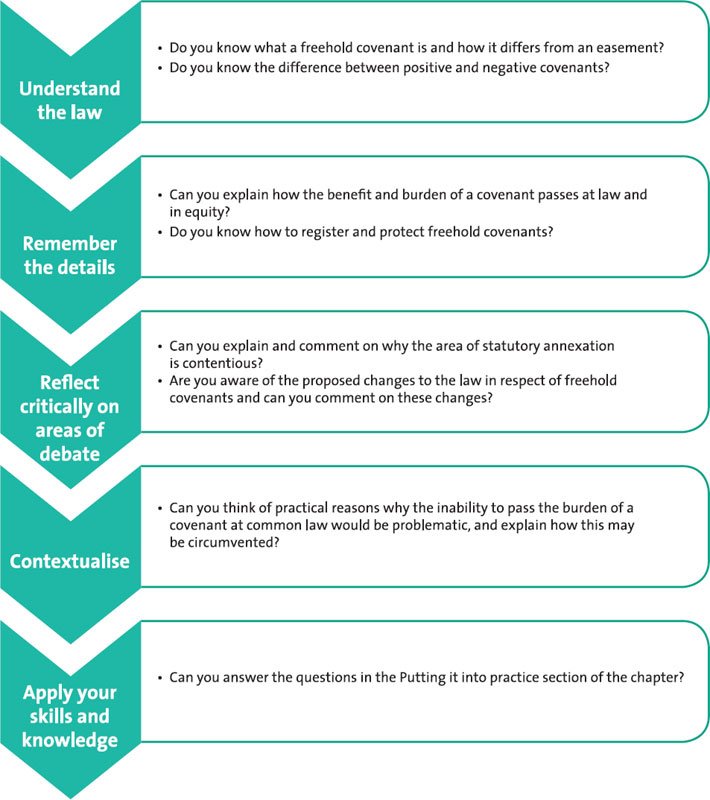

Revision objectives

A covenant is a promise made by deed.

Freehold covenants are extremely wide in nature and, as such, they can encompass almost any topic. Examples of the different kind of freehold covenant you might more commonly come across are:

not to build on the land;

not to build on the land;

not to use the property for business purposes; not to keep any animal other than domestic pets on the land;

not to use the property for business purposes; not to keep any animal other than domestic pets on the land;

not to use the property for the sale of alcoholic liquor;

not to use the property for the sale of alcoholic liquor;

not to park a caravan in the driveway;

not to park a caravan in the driveway;

to keep boundary fences in good repair and condition.

to keep boundary fences in good repair and condition.

Common Pitfalls

The concept of leasehold covenants should not be confused with freehold covenants, however. Whereas freehold covenants are promises to do (or not to do) something on your own land, leasehold covenants are promises as to how a landlord and tenant will conduct themselves for the duration of a lease. The two concepts are distinct entities with entirely different sets of rules relating to their existence and transmission, and as such they should be viewed separately.

Positive and negative covenants

Covenants can be positive or negative in nature. Whilst negative covenants will usually bind successors in title to the burdened land, positive covenants do not.

Negative, or ‘restrictive’, covenants prevent or limit the landowner’s use of the land in some way, as in the case of a covenant not to build on the land.

Positive covenants require the landowner to do something in relation to their land, such as to maintain the boundary fences to the property.

Common Pitfalls

Consider the wording of the covenant carefully and do not be caught out by it. Some covenants may appear to be positive but are actually negative in practice, and vice versa. For example, a covenant to build only a single dwelling house on the land in effect is in reality a restriction preventing the landowner from building multiple dwelling houses. It therefore appears to be positive in nature, but it is negative in its effect.

In Co-operative Retail Services Limited v Tesco Stores Limited (1998) 76 P&CR 328, Millet LJ said:

‘A restrictive covenant is a burden, not on the owner’s pocket, but on his land; he can comply with it completely by complete inaction.’

This is often referred to as the ‘hand in pocket’ rule. It means that, whilst a landowner can comply with a negative covenant simply by refraining from doing the restricted act, in order to comply with a positive covenant, the landowner will have to undertake some form of action, often at his own expense.

Understanding: enforceability of freehold covenants

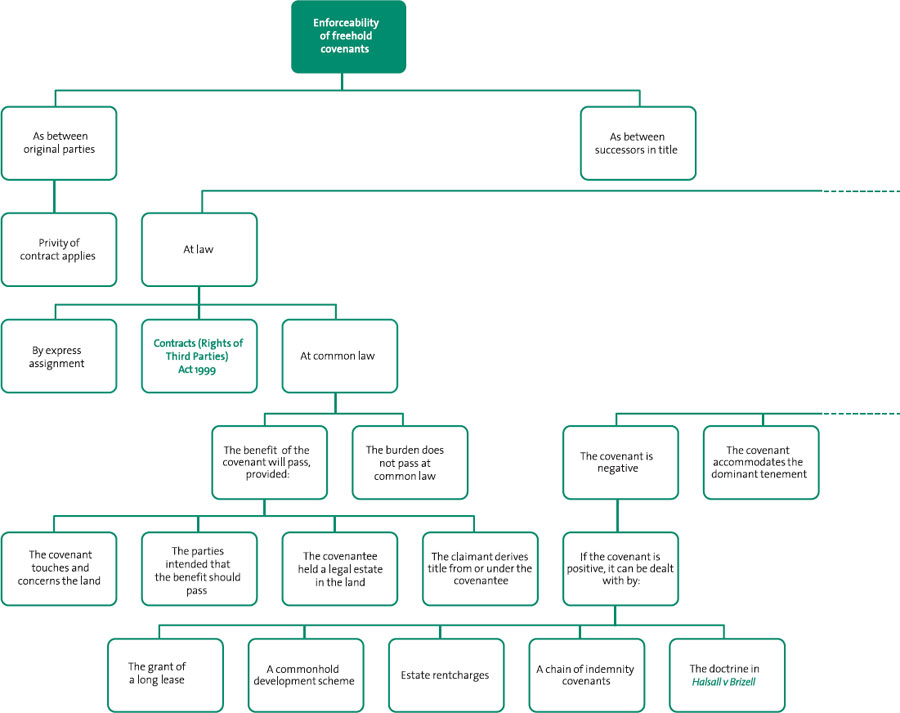

As between the original parties

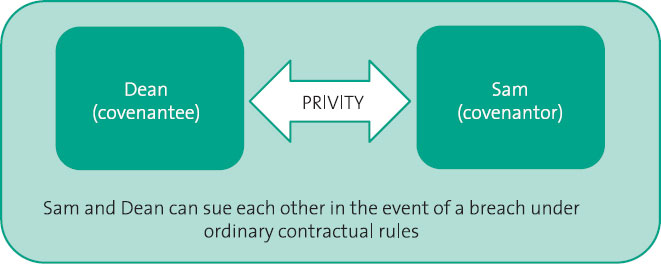

The original parties to the covenant are bound by the ordinary rules of privity of contract.

The rules of privity of contract apply regardless of whether the covenant is positive or negative in nature.

Transmission of the benefit at law

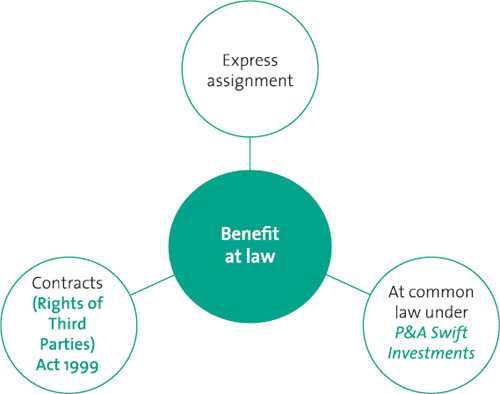

There are three ways in which the benefit of a covenant can be passed at law:

Express assignment

The original covenantee can expressly assign the benefit of the covenant to their successor in title in writing, under s 136 LPA 1925.

Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999

It is also possible that the benefit of the covenant might be transferred under s 1 Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. However, the provisions only apply to covenants created after 11 May 2000 and require the covenant to be specifically worded so as to include successors in title of the covenantee.

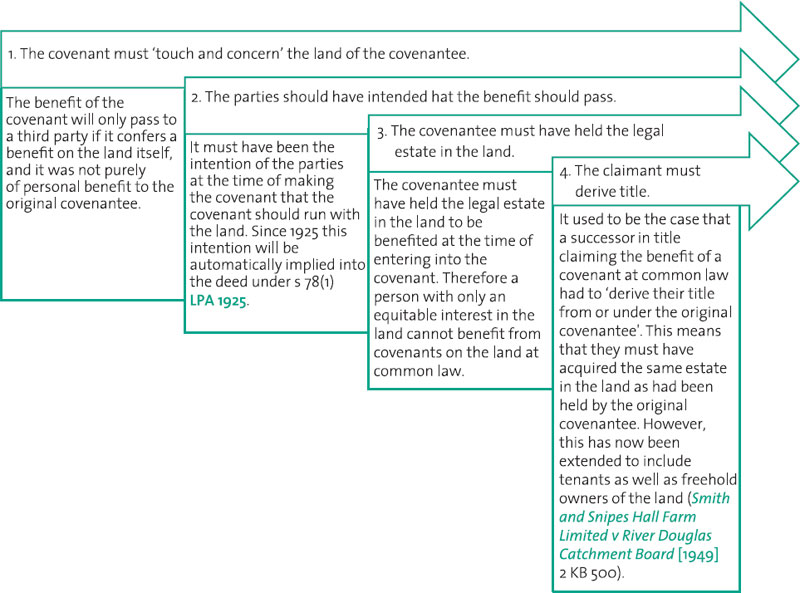

At common law

At common law, the benefit of any freehold covenant is allowed to pass to a successor in title of the original covenantee (the person with the benefit of the covenant), provided the four conditions set out in the House of Lords case of P&A Swift Investments v Combined English Stores Group plc [1988] are met. This is regardless of whether the covenant is positive or negative in nature.

Transmission of the burden at law

If the original covenantor sells their land, the burden of the covenant will not pass to their successors in title. This is regardless of whether the covenant is positive or negative in nature (Austerberry v Corporation of Oldham (1885); Rhone v Stevens [1994] 2 AC 310).

The burden does not pass at common law.

Instead, the original covenantor will remain liable for all breaches of the covenant, regardless of whether they are committed by them or by their successors in title. This is unless a contrary intention is expressed in the original covenant (s 79 LPA 1925).

Facts: The owners of Aintree Racecourse questioned the validity of a freehold covenant that stated that the land should only be used for the purpose of horseracing. They wanted to sell the land to a developer. Held: The original covenantors would remain liable for breaches of covenant, even after they had sold their interest in the land.

Principle: At common law, the burden of a covenant will not pass to successors in title.

Application: Use this case to support your argument that the sellers of land burdened by a covenant will remain liable at law for breaches of that covenant after the sale of the property.

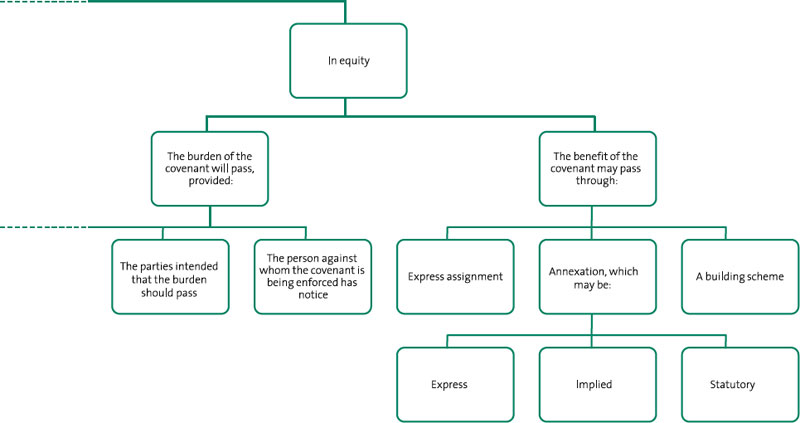

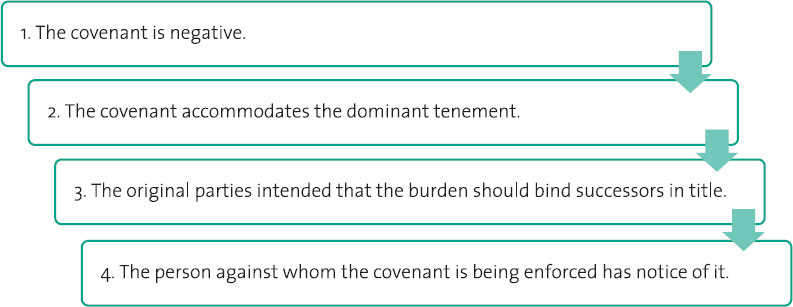

Transmission of the burden in equity

Whilst the burden of a covenant cannot pass at common law, equity will allow the burden of a freehold covenant to be transmitted to successors in title provided that:

The rule in Tulk v Moxhay (1848) 2 Ph 744

Accommodating the dominant tenement:

Case precedent – LCC v Allen [1914] 3 KB 642

Facts: A developer entered into a covenant with London County Council, in return for being given permission to build a new street, that he would leave the land at the end of the street undeveloped. The developer then sold the land to a third party, who wished to build on it. Held: The covenant could not be enforced against the third party, as the Council did not own any land that benefited from the terms of the covenant.

Application: Use this case to illustrate a situation in which the covenant will not be held to accommodate the dominant tenement.

It should be noted that the intention of the original parties to bind successors in title to the property can be either expressly evidenced or implied under s 79 of the Law of Property Act 1925, as we saw earlier in the chapter.

Aim Higher

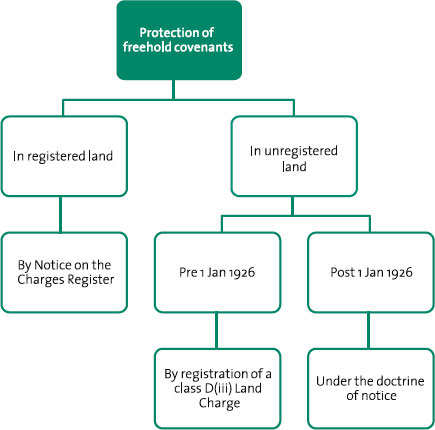

Notice, in this context, means that, in the case of registered land, the restrictive covenant must be entered on the Charges Register of the burdened property at the Land Registry as a Notice, and in the case of unregistered land must be registered as a Class D(ii) Land Charge under the Land Charges Act 1972. This is unless the covenant was created before 1 January 1926, in which case the traditional doctrine of notice will apply.

Transmission of the benefit in equity

In order for the burden of the covenant to pass in equity, the benefit of the covenant must also be shown to pass in equity. This can be done in one of three ways:

by express assignment of the benefit of the covenant; or

by express assignment of the benefit of the covenant; or

by annexation; or

by annexation; or

under the rules relating to building schemes.

under the rules relating to building schemes.

Express assignment of the benefit

The benefit of a covenant can be expressly assigned on the sale of the land provided:

1. the assignment is made at the time of the transfer; and

2. the benefited land is identifiable in that transfer.

(Re Union of London and Smith’s Bank Ltd’s Conveyance [1933] Ch 611)

Aim Higher

Can you think of a problem with this method of passing the benefit of a covenant in equity? Express assignment is not automatic and must be repeated every time the land transfers ownership. If this is not done, the benefit of the covenant is lost.

Annexation means that when the covenant was made, it must have been annexed, or permanently attached to, the land itself, and not just to the person with the benefit of the covenant. There are three types of annexation: express, implied or statutory.

Express annexation

Express annexation takes place when the express wording of the covenant shows that it was the intention of the original parties to the agreement that the benefit of the covenant should run with the land.

Case precedent – Rogers v Hosegood [1900] 2 Ch 288

Facts: A covenant that stated expressly that it was made ‘for the benefit of’ particular land was held to be annexed to the land, because it demonstrated a clear intention that the benefit should run with the land itself.

Principle: Express wording in the covenant will amount to express annexation where the wording shows that it was the intention of the original parties that the covenant should run with the land.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the kind of wording in the deed of covenant that will constitute express annexation.

Case precedent – Renals v Cowlishaw (1878) 9 Ch D 125

Facts: In this case the court found that the word ‘assigns’ was not enough to link any successors in title with the benefited land.

Principle: Express wording in the covenant will amount to express annexation where the wording shows that it was the intention of the original parties that the covenant should run with the land.

Application: Use this case to show that, if the benefit of the covenant is to be shown to run with the land through express annexation, the wording of the covenant must be both clear and precise.

Case precedent – Marquess of Zetland v Driver [1939] Ch 1

Facts: A covenant was expressed to be for the benefit of the covenantee’s retained land ‘and each and every part thereof’. This was considered sufficient to ensure that the parts of the land retained that were actually affected by the breach could sue under the terms of the covenant.

Application: Use this case to show that, where the wording of the covenant is clear and precise, the benefit of the covenant will run with the land through express annexation.

In addition to clear wording in the covenant itself, in order for express annexation to take place the whole of the land retained by the covenantee must be capable of benefiting from the covenant. It is not sufficient that only part of the land that has the benefit of the covenant will gain from it.

Case precedent – Re Ballard’s Conveyance [1927] Ch 473

Facts: A 17,000-acre estate sold off 16 acres of land at one edge of the estate, entering into a covenant with the buyer that the land should not be built upon. Held: The benefit of the covenant could not run on the sale of the estate, because it was not realistic to say that the whole of the estate benefited from the covenant. Only the part of the estate nearest to the boundary with the land that had been sold could benefit.

Principle: In order for express annexation to take place, the whole of the land retained by the covenantee must be capable of benefiting from the covenant.

Application: Compare this case with the facts of your own scenario to show that a covenant will or will not pass with the land in question.

The application of the rule set out in Re Ballard’s Conveyance will turn upon the facts of each individual case. However, the rule has been relaxed in recent years.

Case precedent – Marten v Flight Refuelling Ltd [1962] Ch 115

Facts: The court made a finding that a covenant to use land, sold for agricultural purposes only, was annexed for the benefit of the whole of a 7,500-acre estate.

Principle: In order for express annexation to take place, the whole of the land retained by the covenantee must be capable of benefiting from the covenant.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the recent relaxation in the rule set out in Re Ballard’s Conveyance.

Implied annexation is very rare, and something which can only be done by the courts. The courts will imply annexation if they find that the circumstances indicate an intention to benefit the land.