Forming the Agreement

2

Forming the Agreement

Contents

2.3 Deeds and other formalities

2.4 General lack of formal requirement

2.5 The external signs of agreement

2.8 Unilateral and bilateral contracts

2.13 Acceptance and the termination of an offer

2.15 Certainty in offer and acceptance

Formalities. To what extent does English law use formal mechanisms to decide whether an agreement has been reached? Generally, this will only be where a ‘deed’ is used, or where a statute requires formality in relation to a particular type of contract.

Formalities. To what extent does English law use formal mechanisms to decide whether an agreement has been reached? Generally, this will only be where a ‘deed’ is used, or where a statute requires formality in relation to a particular type of contract.

More generally there is no requirement of writing or other formality. The courts decide whether an agreement has been reached by looking at what the parties have said or done as indicators of whether they intended to make an agreement.

More generally there is no requirement of writing or other formality. The courts decide whether an agreement has been reached by looking at what the parties have said or done as indicators of whether they intended to make an agreement.

The most common indicators will be a matching ‘offer’ and ‘acceptance’. The identification of a matching offer and acceptance is the most common way for the courts to find that an agreement has been made.

The most common indicators will be a matching ‘offer’ and ‘acceptance’. The identification of a matching offer and acceptance is the most common way for the courts to find that an agreement has been made.

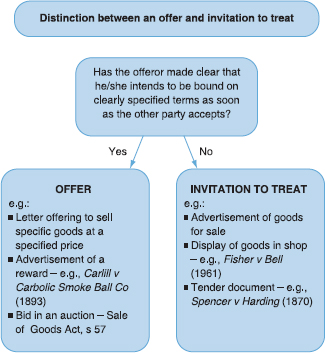

An offer must be distinguished from an invitation to treat, and an acceptance from a counter offer.

An offer must be distinguished from an invitation to treat, and an acceptance from a counter offer.

Particular problems arise in relation to the following:

Particular problems arise in relation to the following:

Unilateral (as opposed to bilateral) contracts. The offer in a unilateral contract (for example, an offer of a reward for the return of property) may be made to the world, and the acceptance may take the form of performing an action (for example, the return of the property).

Unilateral (as opposed to bilateral) contracts. The offer in a unilateral contract (for example, an offer of a reward for the return of property) may be made to the world, and the acceptance may take the form of performing an action (for example, the return of the property).

The ‘battle of the forms’. Where both parties try to contract on their own standard terms, and these are inconsistent, which should prevail?

The ‘battle of the forms’. Where both parties try to contract on their own standard terms, and these are inconsistent, which should prevail?

Contracting at a distance. If the contract is made by letter, fax, email, or over the web, when and where does it take effect? Special rules apply to posted acceptances, as opposed to those communicated by telephone or electronically.

Contracting at a distance. If the contract is made by letter, fax, email, or over the web, when and where does it take effect? Special rules apply to posted acceptances, as opposed to those communicated by telephone or electronically.

Revocation of offers. An offer can generally be revoked at any time before it is accepted, provided that the revocation is communicated to the offeree.

Revocation of offers. An offer can generally be revoked at any time before it is accepted, provided that the revocation is communicated to the offeree.

Certainty. The courts require an agreement to be ‘certain’, and will not enforce an ‘agreement to agree’.

Certainty. The courts require an agreement to be ‘certain’, and will not enforce an ‘agreement to agree’.

The main subject matter of this chapter is the means by which the courts decide whether parties have reached an agreement that is potentially one which the courts will enforce. A related question is that of why and how the law of contract becomes engaged in dealing with the parties’ transaction. There are several potential reasons. First, it might be the case that the courts will simply be responding to the wishes of the parties. In other words, the law is acting in a facilitative way. The parties have intentionally formulated their agreement as a contract, and now wish to make use of the mechanism of the courts to resolve a dispute. They can choose not to use the courts if they wish, and indeed many commercial disputes are settled by alternative methods such as arbitration or mediation. Such methods may make reference to the law of contract as it is thought it would be applied by the courts, but essentially the parties have in such a situation decided to take their dispute out of the formal legal process. Thus, the decision to engage with the law of contract is in the hands of the parties.

Another reason for the courts’ involvement may, however, be where there is a dispute as to whether there is a contract at all. This might be because one of the parties disputes the fact of agreement, or wishes to argue that although there is an agreement, it is unenforceable. If the courts become involved, and again there is an element of choice in that one party must initiate an action by issuing a claim form, it will be against the wishes of one of the parties. That party will be arguing that there is no contract, and that therefore the courts should not be involved at all. In this situation, the court is not acting in a purely facilitative way, but is saying to one of the parties that although it thought that it was not entering into a binding contract, in fact it was, and therefore is obliged to submit to the jurisdiction of the court. The extent to which parties can deliberately exclude an agreement from the jurisdiction of the court is considered further in Chapter 4, in connection with the requirement of ‘intention to create legal relations’.

A third possibility which now exists is that a third party who claims to be entitled to a benefit under a contract may initiate an action against one or other of the contracting parties.1 In theory, it is possible for this to arise in a situation where neither of the alleged contracting parties accepts that it has made a binding contract. The court, if it upholds the third party’s claim, will in effect be overriding the wishes of the two parties who made the agreement. In doing so, it is likely to be acting to protect the reasonable expectations of the third party. To achieve this, it will hold that the parties have made a binding agreement, even though they dispute that they have done so.

In all these situations, however, the concept of an ‘agreement’ forms the basis of the court’s intervention. As indicated in Chapter 1, this book takes as its subject matter the enforcement of agreements, entered into more or less voluntarily, concerning the transfer of goods or other property (permanently or temporarily) or the supply of services. That being so, it becomes important to identify when an agreement has been reached. There are two main ways in which this might be achieved. First, it might be done by identifying certain formal procedures, and deeming the following of those formalities as sufficient to establish that there was an agreement. Second, it might be done by trying to determine whether there was a ‘meeting of the minds’ of the parties concerned. In practice, English law uses both approaches.

The formal test of agreement is achieved by the concept of the ‘deed’. This is a formal written document, signed and, traditionally, sealed (though this is no longer a requirement since the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989). The existence of a deed will be regarded as indicating that there is an agreement. There are certain contracts where a deed is required (and these situations are considered further in Chapter 3), but the device can be used for any type of contract if the parties so wish. This type of formality should be distinguished from the situations where some special procedure is required in addition to the finding of an agreement. In these situations there may be an agreement, but the courts will not enforce it unless certain formalities have been complied with. Three examples will be mentioned here. First, by virtue of s 2(1) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989, all contracts involving the sale, or other disposal, of an interest in land must be in writing and signed by the parties. The need for writing in relation to contracts concerning land is of long standing in English law, though prior to 1989 the requirement was only that the contract should be evidenced in writing, and signed by the person against whom it was to be enforced.2 Although, in practice, the vast majority of such contracts were put into written form, this formulation left open the possibility of a verbal contract being evidenced by, for example, a letter signed by the relevant party. The 1989 amendment of this rule means that the agreement itself must be in writing and signed by both parties. The justification for the stricter rules that apply in relation to this type of contract is that contracts involving land are likely to be both complicated and valuable. Many commercial contracts, however, are also complex and valuable, yet there is no requirement for a written agreement (though, in practice, there is likely to be one). A second type of contract where there is a requirement of a certain degree of formality arises under the Consumer Credit Act 1974, which requires that contracts of hire purchase, and other credit transactions, should be in writing and signed.3 This is a protective provision, designed to make sure that the individual consumer has written evidence of the agreement, and has the opportunity to see all its terms. A similar protective procedure operates in relation to contracts of employment, though here the requirement is simply that the employee should receive a written statement of terms and conditions within a certain period of starting the job, rather than that the agreement itself should be in writing.4

A third situation where formality is required was the subject of consideration by the House of Lords in Actionstrength Ltd v International Glass Engineering.5 The case concerned the requirement in s 4 of the Statute of Frauds 1677 that an agreement to guarantee the debt of a third party must, in order to be enforceable, be in writing and signed by the guarantor.

The claimant was a subcontractor who had worked for the main contractor on a construction contract. When the main contractor became insolvent, the claimant sought to recover under an alleged oral guarantee of payment given by the party for whom the building was being constructed. In the Court of Appeal, it was held that the claimant could not succeed because an oral guarantee was unenforceable by virtue of s 4 of the 1677 Act.

In the House of Lords, the claimant argued that even if the Act applied, the defendant should not be allowed to rely on it, on the grounds that it would be unconscionable to do so. The claimant’s argument was based on ‘estoppel’ – a concept, which, when it operates, prevents a party to an action relying on a point, where their words or behaviour have previously indicated that they would not rely on it. The defendant had allowed the claimant to run up the debt owed by the main contractor, knowing that it was relying on the guarantee. It was held that the effect of s 4 could not be overturned by an estoppel, at least not unless there had been a specific assurance that the statute would not be relied on.

The case emphasises the continuing importance of the Statute of Frauds in this area, and the need to ensure that any ‘promise to answer for the debt, default or miscarriages of another’ is put in writing.

In most cases, however, English law imposes no formal requirements and looks simply for an agreement between two parties. In other words, the contract does not have to be put into writing, or signed, nor does any particular form of words have to be used. A purely verbal exchange can result in a binding contract. All that is needed is an agreement. This simple assertion, however, masks a considerable problem in identifying precisely what is meant by an agreement. This may seem easy enough: it is simply a question of identifying a ‘meeting of the minds’ between the parties at a particular point in time. That, however, is easier said than done. By the time two parties to a contract have arrived in court, they are clearly no longer of one mind. They may dispute whether there was ever an agreement between them at all or, while accepting that there was an agreement, they may disagree as to its terms. How are such disputes to be resolved? Clearly, the courts cannot discover as a matter of fact what was actually going on in the minds of the parties at the time of the alleged agreement. Nor are they prepared to rely solely on what the parties now say was in their minds at that time (which would be a ‘subjective’ approach), even if they are very convincing. Instead, the courts adopt what is primarily an ‘objective’ approach to deciding whether there was an agreement and, if so, what its terms were. This means that they look at what was said and done between the parties from the point of view of the ‘reasonable person’ and try to decide what such a person would have thought was going on.

A further complication with regard to ‘agreement’ arises once parties start to contract over a distance – that is, not face to face. The particular problems relating to contracts made by post or other forms of distance communication are discussed later in this chapter.6 Suffice it to say here that once this type of contracting is allowed, the idea that at any particular point in time there is a ‘consensus ad idem’, a ‘meeting of the minds’, becomes very difficult to sustain.7 If there is a significant gap in time between an ‘offer’ and its ‘acceptance’, the likelihood is that in a significant number of cases the parties will not actually have been in agreement at the point when the courts decide that a contract was formed.

2.4.1 IN FOCUS: AGREEMENT OR RELIANCE?

It has been argued by Collins that the ‘objective’ approach to ‘agreement’ means that the courts are not actually looking for agreements between the parties but:

whether or not the negotiations and conduct have reached such a point that both parties can reasonably suppose that the other is committed to the contract so that it can be relied upon.8

In other words, it is behaviour justifying ‘reasonable reliance’ on the other party’s commitment that the courts are in fact looking for, rather than ‘agreement’, whether looked at subjectively or objectively.9 There is, however, not very much to choose between an approach that uses the language of ‘objective agreement’ as opposed to that of ‘reasonable reliance’, and certainly little in the way of practical consequence. The former is what is used here, not least because it ties in more comfortably with the language used by the courts, which tends to focus on the presence or absence of ‘agreement’. Provided that it is remembered that what is required is objective evidence of such agreement, rather than an actual ‘meeting of the minds’, this analysis will work satisfactorily, without giving a misleading picture of what is actually happening.

2.4.2 PROMISOR, PROMISEE AND DETACHED OBJECTIVITY

Although it is clear that an objective approach to agreement has to be adopted, as has been pointed out by McClintock and Howarth,10 there are different types of objectivity. There is (a) ‘promisor objectivity’, where the court tries to decide what the reasonable promisor would have intended; (b) ‘promisee objectivity’, where the focus is on what the reasonable person being made a promise would have thought was intended; and (c) ‘detached objectivity’, which views what has happened through the eyes of an independent third party. In Smith v Hughes,11 for example, where the dispute was over what type of oats the parties were contracting about, the test was said to be whether the party who wishes to deny the contract acted so that ‘a reasonable man would believe that he was assenting to the terms proposed by the other party’: in other words, promisee objectivity. As we shall see, however, in subsequent chapters, the courts are not consistent as to which of these types of objectivity they use, changing between one and another as seems most appropriate in a particular case.

The use of the objective approach where there is a dispute as to whether the parties were ever in agreement is discussed further in Chapter 9, 9.5.1–9.5.3.

2.4.3 STATE OF MIND

The objective approach must, however, take account of all the evidence. Even if A has acted in a way that would reasonably cause B to assume a particular state of mind as regards an agreement, if B’s behaviour, objectively viewed, indicates that such an assumption has not been made by B, the courts will take account of this. The Hannah Blumenthal,12 for example, was a case concerning the sale of a ship, where the point at issue was whether the parties had agreed to abandon their dispute. The behaviour of the buyers was such that it would have been reasonable for the sellers to have believed that the action had been dropped. In fact, the sellers had continued to act (by seeking witnesses, etc.) in a way that indicated that they did not think the action had been dropped. This evidence of their actual response to the buyers’ behaviour overrode the conclusion that the court might well have reached by applying a test based on an objectively reasonable response.13

As we have seen, the process by which the courts try to decide whether the parties have made an agreement does not necessarily involve looking for actual agreement, but rather for the external signs of agreement. The classical theory of contract relied on a number of specific elements, which were regarded as both necessary and sufficient to identify an agreement that is intended to be legally binding. These were:

(a) offer;

(b) acceptance; and

(c) consideration.

These three factors, together with an overarching requirement that the court is satisfied that there was an intention to create legal relations, formed the classical basis for the identification of contracts in English law. As far as offer and acceptance are concerned, in the modern law the courts have, as will be noted below, at various times recognised the difficulty of analysing all contractual situations in terms of these concepts. Some attempts have been made to apply a more general test of ‘agreement’. This involves taking offer and acceptance as the normal basis for the creation of a contract, but recognising that not all contracts will be made in this way. The overall test is simply whether there is ‘agreement’, with this being determined by whether it is possible to identify the terms sufficiently that the contract is enforceable.14

The rest of this chapter explores the current English law approach to offer and acceptance in detail. Consideration is dealt with in Chapter 3 and the intention to create legal relations in Chapter 4.

The rules of ‘offer’ and ‘acceptance’, and their use as the basis for deciding whether there has been an agreement between contracting parties, derives, as with much of the classical law of contract, from late eighteenth and early nineteenth century case law.15

An offer may be defined as an indication by one person that he or she is prepared to contract with one or more others, on certain terms, which are fixed, or capable of being fixed, at the time the offer is made. Thus, the statement ‘I will sell you 5,000 widgets for £1,000’ is an offer, as is the statement ‘I will buy from you 5,000 shares in X Ltd, at their closing price on the London Stock Exchange next Friday’. In the former case, the terms are fixed by the offer itself; in the latter they are capable of becoming fixed on Friday, according to the price of the shares at the close of business on the Stock Exchange. The offer may be made by words, conduct or a mixture of the two. The concept applies most easily to a situation such as that given in the above example where there are two parties communicating with each other about a commercial transaction. It fits less easily, as will be seen below, in many other everyday transactions, such as supermarket sales, or those involving the advertisement of goods in a newspaper or magazine. What the courts will look for, however, is some behaviour that indicates a willingness to contract on particular terms. Once there is such an indication, all that is then required from the other person is a simple assent to the terms suggested, and a contract will be formed. The ‘indication of willingness’ referred to above may take a number of forms – for example, the spoken word, a letter, a fax message, an email or an advertisement on a website. As long as it communicates to the potential acceptor or acceptors the basis on which the offeror is prepared to contract, then that is enough. It is not necessary for the offer itself to set out all the terms of the contract. The parties may have been negotiating over a period of time, and the offer may simply refer to terms appearing in earlier communications. That is quite acceptable, provided that it is clear what the terms are.

2.7.1 DISTINCTION FROM ‘INVITATION TO TREAT’

As we have noted, the objective of looking for ‘offer and acceptance’ is to decide whether an agreement has been reached. It is important, therefore, that behaviour which may have some of the characteristics of an offer should not be treated as such if, viewed objectively, that was not what was intended. Once a statement or action is categorised as an offer, then the party from whom it emanated has put itself in the position where it can become legally bound simply by the other party accepting. It must be clear, therefore, that the statement or action indicates an intention to be bound, without more. The courts have traditionally approached this issue by drawing a distinction between an offer and an ‘invitation to treat’.

Sometimes a person will wish simply to open negotiations, rather than to make an offer that will lead immediately to a contract on acceptance. If I wish to sell my car, for example, I may enquire if you are interested in buying it. This is clearly not an offer. Even if I indicate a price at which I am willing to sell, this may simply be an attempt to discover your interest, rather than committing me to particular terms. The courts refer to such a preliminary communication as an ‘invitation to treat’ or, even more archaically, as an ‘invitation to chaffer’. The distinction between an offer and an invitation to treat is an important one, but is not always easy to draw. Even where the parties appear to have reached agreement on the terms on which they are prepared to contract, the courts may decide that the language they have used is more appropriate to an invitation to treat than an offer.

This was the view taken in Gibson v Manchester City Council.16

Key Case Gibson v Manchester City Council (1979)

Facts: Mr Gibson was a tenant of a house owned by Manchester City Council. The Council, which was at the time under the control of Conservative Party members, decided that it wished to give its tenants the opportunity to purchase the houses which they were renting. Mr Gibson wished to take advantage of this opportunity and started negotiations with the Council. He received a letter which indicated a price, and which stated ‘The Corporation may be prepared to sell the house to you’ at that price. It also instructed Mr Gibson, if he wished to make ‘a formal application’, to complete a form and return it. This Mr Gibson did. At this point, local elections took place, and control of the Council changed from the Conservative Party to the Labour Party. The new Labour Council immediately reversed the policy of the sale of council houses, and refused to proceed with the sale to Mr Gibson. At first instance and in the Court of Appeal,17 it was held that there was a binding contract, and that Mr Gibson could therefore enforce the sale. Lord Denning argued that it was not necessary to analyse the transaction in terms of offer and acceptance. He suggested that:

You should look at the correspondence as a whole and at the conduct of the parties and see from there whether the parties have come to an agreement on everything that was material. If by their correspondence and their conduct you can see an agreement on all material terms, which was intended thenceforward to be binding, then there is a binding contract in law even though all formalities have not been gone through.18

Held: The House of Lords firmly rejected Lord Denning’s approach. Despite the fact that all terms appeared to have been agreed between the parties, the House held that there was no contract. The language of the Council’s letter to Mr Gibson was not sufficiently definite to amount to an offer. It was simply an invitation to treat. Mr Gibson had made an offer to buy, but that had not been accepted.

Do you think the House of Lords would have come to the same conclusion if the Council’s letter to Mr Gibson had said that it ‘is prepared to sell the house’ at the specified price, rather than that it ‘may be prepared to sell’?

The narrowness of the distinction being drawn can be seen by comparing this case with Storer v Manchester City Council,19 where on very similar facts a contract was held to exist, as Mr Storer had signed and returned a document entitled ‘Agreement for Sale’. This document was deemed to be sufficiently definite to amount to an offer from the Council that Mr Storer had accepted. As regards the state of mind of the parties in the two cases, however, it is arguable that there was little difference. In both, each party had indicated a willingness to enter into the transaction, and there was agreement on the price. The fact that the courts focus on the external signs, rather than the underlying agreement, however, led to the result being different in the two cases.

Finally, although the House of Lords in Gibson rejected Lord Denning’s approach to finding agreement, a very similar approach has now been adopted in relation to certain situations arising in connection with commercial contracts that have been started without a formal agreement having been concluded. These cases are discussed below at para 2.11.5.

2.7.2 IN FOCUS: THE POLITICAL CONTEXT

Before leaving these cases, it should be noted that there was potentially a political dimension to the decisions in Storer and Gibson. The question of the sale of council houses was at the time a very controversial political issue, with the Conservative Party strongly in favour and Labour vehemently opposed. In Manchester, the local electors had decided to vote in a Labour Council, and it might have been reasonable to assume that one of the reasons for this was opposition to the previous Conservative Council’s approach to the sale of council houses. In such a situation, to decide strongly in favour of enforcing the sale of a council house (particularly since there were, apparently, ‘hundreds’ of other cases similar to that of Mr Gibson)20 might have been seen as an intervention by the judges that would have the effect of disregarding the wishes of the electorate. Where the case was clear-cut (as in Storer), the courts would be obliged to respect the individual’s vested rights; where there was ambiguity, however (as in Gibson), there would be an argument for deciding the case in a way that complied with the political decision indicated by the results of the election. There is, of course, no indication in the speeches in the House of Lords of any such political considerations having any effect on their Lordships’ opinions. However, it has been strongly argued that judges can be influenced, consciously or unconsciously, by political matters,21 and it is possible that this may have been a factor tipping the balance against Mr Gibson. In any case, the Storer and Gibson decisions are good examples of the fact that decisions on the law of contract operate in a social and political context, and their interrelationship with that context should not be ignored.

Another area of difficulty arises in relation to the display of goods in a shop window, or on the shelves of a supermarket, or other shop where customers serve themselves. We commonly talk of such a situation as one in which the shop has the goods ‘on offer’. This is especially true of attractive bargains that may be labelled ‘special offer’. Are these ‘offers’ for the purpose of the law of contract? The issue has been addressed in a number of criminal cases where the offence in question was based on there being a ‘sale’ or an ‘offer for sale’. These cases are taken to establish the position under the law of contract, even though they were decided in a criminal law context. The Court of Appeal has more recently suggested that it is not appropriate to use contractual principles in defining the behaviour which constitutes a criminal offence, in this case relating to an offer to supply drugs.22 This does not, however, affect the contractual rules deriving from older criminal cases where this was done. The first to consider is Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists.23

Key Case Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (1953)

Facts: Section 18(1) of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1933 made it an offence to sell certain medicines unless the sale was ‘effected by, or under the supervision of, a registered pharmacist’. Boots introduced a system under which some of these medicines were made available to customers on a self-service basis. There was no supervision until the customer went to the cashier. At this point, a registered pharmacist would supervise the transaction and could intervene, if necessary. The Pharmaceutical Society claimed that this was an offence under s 18, because, it was argued, the sale was complete when the customer took an article from the shelves and put it into his or her basket.

Held: The Court of Appeal held against the Pharmaceutical Society. It decided that the sale was made at the cash desk, where the customer made an offer to buy, which could be accepted or rejected by the cashier. The reason for this decision was that it is clearly unacceptable to say that the contract is complete as soon as the goods are put into the basket, because the customer may want to change his or her mind, and it is undoubtedly the intention of all concerned that this should be possible. The display of goods is therefore an invitation to treat and not an offer.

With respect to the Court of Appeal, the conclusion that was reached was not necessary to avoid the problem of the customer becoming committed too soon. It would have been quite possible to have said that the display of goods is an offer, but that the customer does not accept that offer until presenting the goods to the cashier.24 This analysis would, of course, also have meant that the sale took place at the cash desk and that no offence was committed under s 18. Strictly speaking, therefore, the details of the Court of Appeal’s analysis in this case as to what constitutes the offer, and what is the acceptance, may be regarded as obiter. It has, however, generally been accepted subsequently that the display of goods within a shop is an invitation to treat and not an offer.

2.7.4 IN FOCUS: THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONTEXT

The decision in this case was treated by the Court of Appeal very much as a ‘technical’ one on the law of contract. There were, however, several other broader issues that were involved in it. First, there was the issue of the degree of supervision necessary to protect the public in relation to the sale of certain types of pharmaceutical product. Second, there was the potential effect on the employment position of pharmacists – the self-service arrangement would probably have the effect of reducing the number of pharmacists that Boots, or other chemists adopting a self-service system, would need to employ. Third, there was the question of whether the law on formation of contracts was to be developed in a way that helped or hindered the growth of the self-service shop. On the first issue Somervell LJ emphasised that the substances concerned were not ‘dangerous drugs’.25 The implication is that the system of control operating under Boots’ self-service scheme was sufficient to fulfil the objective of the 1933 Act in protecting the public. The second issue, the effect on pharmacists, was not addressed at all, even though this must have been one of the main reasons for the action being brought by the Pharmaceutical Society. Collins has suggested that the court may not have been impressed ‘by the desire of the pharmacists to retain their restrictive practices’,26 but this does not appear from the judgments at all. As regards the final issue, the court noted that the self-service arrangement was a ‘convenient’ one for the customer.27 It is also, of course, an efficient one for the shopkeeper, enabling the display of a wide range of goods with a relatively small number of staff. The self-service format has become so dominant in shops of all kinds today that it is important to remember that in the early 1950s it was only gradually being adopted. The decision in the Boots case, if it had gone the other way, would have hindered (though probably not halted) its development.28 The Court of Appeal therefore can be seen by this decision to be making a contribution to the way in which the retail trade developed over the next 10 years.

2.7.5 SHOP WINDOW DISPLAYS

The slightly different issue of the shop window display was dealt with in Fisher v Bell.29 The defendant displayed in his shop window a ‘flick-knife’ with the price attached. He was charged with an offence under s 1(1) of the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959, namely ‘offering for sale’ a ‘flick-knife’. It was held by the Divisional Court that no offence had been committed, because the display of the knife was an invitation to treat, not an offer.

Lord Parker had no doubt as to the contractual position:

It is clear that according to the ordinary law of contract the display of an article with a price on it in a shop window is merely an invitation to treat. It is in no sense an offer for sale the acceptance of which constitutes a contract.30

No authority was cited for this proposition, but the approach is certainly in line with that taken in the Boots case. There has never been any challenge to it, and it must be taken to represent the current law on this point. It was followed in Mella v Monahan,31 where a charge of ‘offering for sale’ obscene articles, contrary to the Obscene Publications Act 1959, failed because the items were simply displayed in a shop window.

What are the principles lying behind the decisions in relation to self-service stores and shop window displays? In Boots, the court stressed the need for the shopper to be allowed a ‘change of mind’. As we have seen, however, that does not necessarily require the offer to be made by the customer, just that the acceptance of the offer should be delayed beyond the point when the shopper may legitimately still be deciding whether to purchase. In any case, the argument cannot apply to the shop window cases. The customer who enters the shop will either say ‘I want to buy that item displayed in your window’, which could undoubtedly be treated as an acceptance, or ‘I am interested in buying that item in your window; can I inspect it?’ or ‘can you tell me more about it?’, which would simply be a stage in negotiation. There is no need, therefore, to protect the customer by making the shop window display simply an invitation to treat.

The most likely candidate as an alternative principle on which the decisions are based is freedom of contract. That freedom includes within it the principle that a person can choose with whom to contract – ‘party freedom’.32 On this analysis, the shop transaction needs to be analysed in a way that will allow the shopkeeper to say ‘I do not want to do business with you’. This was the view expressed to counsel by Parke B in the nineteenth-century case of Timothy v Simpson.33 There are two problems, however, with the modern law of contract allowing such freedom in these situations.

First, such freedom has the potential to be used in a discriminatory way.34 Certain types of discrimination – on grounds, for example, of race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age and disability35 – have as a matter of social policy been made unlawful by statute.36 To the extent, therefore, that the common law of contract still allows party freedom to operate in these areas, there is a tension between it and the statutory equality regime. A shopkeeper who discriminates on impermissible grounds in deciding with whom to contract is not forced by the common law to undertake the contractual obligation, but may face an action under the relevant statutory provisions.

Second, application of the ‘party freedom’ principle leads to the conclusion that, as far the law of contract is concerned, a shopkeeper is not bound by any price that is attached to goods displayed in the shop or in the window. He or she is entitled to say to the customer seeking to buy the item ‘… that is a mistake. I am afraid the price is different’. Again, however, there is a conflict with the statutory position. Such action on the part of the shopkeeper would almost certainly constitute a criminal offence under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008.37 Regulation 5 prohibits the giving of misleading information as to the price of goods. An indication is ‘misleading’ if it leads the consumer to think that the price is less than in fact it is.38 Thus, if a shop has a window display indicating that certain special packs of goods are on offer at a low price inside, but in fact none of the special packs is available, an offence will almost certainly have been committed. This was the situation in Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass,39 a case concerning s 11 of the Trade Descriptions Act 1968, which was the predecessor to the current Regulations.

In practice, because of their awareness of the statutory position, and their wish to maintain good relationships with their customers, shops and other businesses are unlikely to insist on their strict contractual rights in situations of this kind. That being the case, the question arises as to whether the rule that it is the customer who makes the offer, and the shopkeeper who has the choice whether or not to accept it, is not ripe for reconsideration.

2.7.7 ADVERTISEMENTS

Where goods or services are advertised, does this constitute an offer or an invitation to treat? It would be possible here for the law also to base its principles on ‘party freedom’: that is, a person putting forward an advertisement should not be taken to be waiving the right as to whom he or she chooses to contract with. In fact, however, the cases in this area show the courts adopting an approach based on pragmatism, rather than on the ‘party freedom’ principle. The answer to the question ‘is this advertisement an offer?’ will generally be determined by the context in which the advertisement appears, and the practical consequences of treating it as either an offer or an invitation to treat.

Generally speaking, an advertisement on a hoarding, a newspaper ‘display’ or a television commercial will not be regarded as an offer. Thus, in Harris v Nickerson,40 the defendant had advertised that an auction of certain furniture was to take place on a certain day. The plaintiff travelled to the auction only to find that the items in which he was interested had, without notice, been withdrawn. He brought an action for breach of contract to recover his expenses in attending the advertised event. His claim was rejected by the Queen’s Bench. The advertisement did not give rise to any contract that all the items mentioned would actually be put up for sale. To hold otherwise would, Blackburn J felt, be ‘a startling proposition’ and ‘excessively inconvenient if carried out’. It would amount to saying that ‘anyone who advertises a sale by publishing an advertisement becomes responsible to everybody who attends the sale for his cab hire or travelling expenses’.41 In other words, the practical consequences of treating the advertisement as an offer would be such that it is highly unlikely that this is what the person placing the advert can have intended. Using an approach based on ‘promisor objectivity’,42 it is concluded that the advertisement is nothing more than an invitation to treat.

It follows from this that these types of advertisement should be regarded simply as attempts to make the public aware of what is available. Such advertisements will often, in any case, not be specific enough to amount to an offer. Even where goods are clearly identified and a price specified, however, there may still not be an offer. A good example of this situation is another criminal law case, Partridge v Crittenden.43

Key Case Partridge v Crittenden (1968)

Facts: The defendant put an advertisement in the ‘classified’ section of a periodical, advertising bramblefinches for sale at 25s each. He was charged under the Protection of Birds Act 1954 with ‘offering for sale’ a live wild bird, contrary to s 6(1).

Held: It was held that he had committed no offence, because the advert was an invitation to treat and not an offer. The court relied heavily on Fisher v Bell,44 and appeared to feel that this kind of advertisement should be treated in the same way as the display of goods with a price attached. Lord Parker also pointed out that if it was an offer, this would mean that everyone who replied to the advertisement would be accepting it, and would therefore be entitled to a bramblefinch. Assuming that the advertiser did not have an unlimited supply of bramblefinches, this could not be what he intended. The advertisement was only an invitation to treat.

This does not mean, however, that all newspaper advertisements will be treated as invitations to treat. If the guiding principle is promisor objectivity, rather than party freedom, then provided that the wording is clear and there are no problems of limited supply, there seems to be no reason why such an advertisement should not be an offer. If, for example, the advertiser in Partridge v Crittenden had said, ‘100 bramblefinches for sale. The first 100 replies enclosing 25s will secure a bird’, then in all probability this would be construed as an offer. An advertisement of a similar kind was held to be an offer in the American case of Lefkowitz v Great Minneapolis Surplus Stores,45 where the defendants published an advertisement in a newspaper, stating: ‘Saturday 9 am sharp; three brand new fur coats, worth to $100. First come first served, $1 each.’ The plaintiff was one of the first three customers, but the firm refused to sell him a coat, because it said the offer was only open to women. The court held that the advertisement constituted an offer, which the plaintiff had accepted, and that he was therefore entitled to the coat.

For Thought

Would it have made any difference to the court’s decision in Lefkowitz if the advertisement had indicated that there were just three coats available, but had not said ‘first come first served’?

Clearly, in this case, the court was rejecting any argument based on party freedom. In this context any such freedom was waived by making such a specific offer to the general public, which did not indicate any intention by the advertiser to put limits on those who were entitled to take advantage of the bargain. The use of such an approach here only serves to highlight the anomaly of the cases on shop sales discussed in the previous section.

2.7.8 CARLILL v CARBOLIC SMOKE BALL CO

In England, the most famous case of an advertisement constituting an offer is Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co.46

Key Case Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co (1893)

Facts: The manufacturers of a ‘smoke ball’ published an advertisement at the time of an influenza epidemic, proclaiming the virtues of their smoke ball for curing all kinds of ailments. In addition, they stated that anybody who bought one of their smoke balls, used it as directed, and then caught influenza, would be paid £100. Mrs Carlill, having bought and used a smoke ball, but nevertheless having caught influenza, claimed £100 from the company. The company argued that the advertisement could not be taken to be an offer that could turn into a contract by acceptance. They claimed that it should be regarded as a ‘mere puff’, which meant nothing in contractual terms. There was, however, apparent evidence of serious intent on the part of the defendants. The advertisement had stated that ‘£1,000 is deposited with the Alliance Bank, showing our sincerity in this matter’. The defendants raised two further objections. First, they argued that the advertisement was widely distributed, and that this was therefore not an offer made to anybody in particular. Second, the defendants said that Mrs Carlill should have given them notice of her acceptance.

Held: The court held in favour of Mrs Carlill. It took the view that the inclusion of the statement about the £1,000 deposit meant that reasonable people would treat the offer to pay £100 as one that was intended seriously, so that it could create a binding obligation in appropriate circumstances, such as those that had arisen. As to the wide distribution of the advert, the court did not regard this as a problem. Offers of reward (for example, for the return of a lost pet or for information leading to the conviction of a criminal) were generally in the same form, and could be accepted by any person who fulfilled the condition. There was plenty of authority to support this, such as Williams v Carwardine.47 Finally, as regards the fact that Mrs Carlill had not given notice of her acceptance, again the court, by analogy with the reward cases, held that the form of the advertisement could be taken to have waived the need for notification of acceptance, at least prior to the performance of the condition which entitled the plaintiff to claim. As Lindley LJ put it:48

I … think that the true view, in a case of this kind, is that the person who makes the offer shows by his language and from the nature of the transaction that he does not expect and does not require notice of the acceptance apart from notice of the performance.

The Smoke Ball Company cannot have expected that everyone who bought a smoke ball would get in touch with them. It was only those who, having used the ball, then contracted influenza who would do so.

This case, therefore, is authority for the propositions, first, that an advertisement can constitute an offer to ‘the world’ (that is, anyone who reads it) and, second, that it may, by the way in which it is stated, waive the need for communication of acceptance prior to a claim under it.

2.7.9 IN FOCUS: CONSUMER PROTECTION

The Carlill case has been viewed as giving a surprisingly broad scope to the situations which will fall within the law of contract.49 Simpson has pointed out that there was much concern at the time about advertisements for dubious ‘medicinal’ products,50 and this may have influenced the court towards finding liability. Nowadays, it would be expected that such situations would be more likely to be dealt with by legislation,51 or by an agency such as the Advertising Standards Authority. This is certainly true of many advertising slogans (for example, ‘Gillette – the Best a Man Can Get’, ‘The Best Hard Rock Album in the World … Ever!’). A contractual action based on these would be doomed to failure. At the time of Carlill’s case, however, the consumer protection role had to be taken by the courts, even if this meant stretching contractual principles to provide a remedy.

Figure 2.1

It should be noted that the offer in Carlill, in Lefkowitz52 and the suggested reformulation of the offer in Partridge v Crittenden53 are all offers of a particular kind, known in English law as an offer in a ‘unilateral’ (as opposed to a ‘bilateral’) contract. It will be convenient at this point to examine the difference between these two types of contract.

The typical model of the bilateral contract arises where A promises to sell goods to B in return for B promising to pay the purchase price. In this situation, the contract is bilateral, because as soon as these promises have been exchanged, there is a contract to which both are bound. In relation to services, the same applies, so that an agreement between A and B that B will dig A’s garden for £20 next Tuesday is a bilateral agreement. Suppose, however, that the arrangement is slightly different, and that A says to B ‘If you dig my garden next Tuesday, I will pay you £20’. B makes no commitment, but says, ‘I am not sure that I shall be able to, but if I do, I shall be happy to take £20’. This arrangement is not bilateral. A has committed himself to pay the £20 in certain circumstances, but B has made no commitment at all. He is totally free to decide whether or not he wants to dig A’s garden or not, and if he wakes up on Tuesday morning and decides that he just does not feel like doing so, there is nothing that A can do about it. If, however, B does decide to go and do the work, this will be regarded as an acceptance of A’s offer of £20, and the contract will be formed. Because of its one-sided nature, therefore, this type of arrangement is known as a ‘unilateral contract’. Another way of describing them is as ‘if’ contracts, in that it is always possible to formulate the offer as a statement beginning with the word ‘if’, followed by the required action: for example, ‘if you dig my garden, I will pay you £20’. The ‘if’ statement must be followed by an action, rather than a promise. ‘If you promise to dig my garden, I will pay you £20’ would create a bilateral contract, if the promise to do the digging was made. As has been noted above, the arrangements in Carlill and Lefkowitz were unilateral: ‘If you use our smoke ball and catch influenza, we will pay you £100’; ‘If you are the first person to offer to buy one of these coats, we will sell it to you for $1’. In each case, it is the performance of an action that creates the contract, not a promise to act.

The distinction between unilateral and bilateral contracts is important in relation to the areas of ‘acceptance’ and ‘consideration’, which are discussed further below.

Some confusion may arise as to what constitutes an offer when a person or, more probably, a company decides to put work out to tender, or seeks offers for certain goods. This means that potential contractors are invited to submit quotations. The invitation may be issued to the world or to specific parties. Generally speaking, such a request will amount simply to an invitation to treat, and the person making it will be free to accept or reject any of the responses. In Spencer v Harding,54 for example, it was held that the issue of a circular ‘offering’ stock for sale by tender was simply a ‘proclamation’ that the defendants were ready to negotiate for the sale of the goods, and to receive offers for the purchase of them. There was no obligation to sell to the highest bidder, or indeed to any bidder at all. The position will be different if the invitation indicates that the highest bid or, as appropriate, the lowest quotation will definitely be accepted. It will then be regarded as an offer in a unilateral contract. The recipients of the invitation will not be bound to reply, but if they do, the one who submits the lowest quotation will be entitled to insist that the contract is made with them. A similar situation arose in Blackpool and Fylde Aero Club Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council.55 The council had invited tenders for the operation of pleasure flights from an airfield. Tenders were to be placed in a designated box by a specified deadline. The plaintiff complied with this requirement, but due to an oversight on the part of the defendant’s employees, the plaintiff’s tender was not removed from the box until the day after the deadline, and was accordingly marked as having arrived late. It was therefore ignored in the council’s deliberations as to who should be awarded the contract. The plaintiff succeeded in an action against the defendant, who appealed. The Court of Appeal noted that, in this type of situation, the inviter of tenders was in a strong position, as he could dictate the terms on which the tenders were to be made, and the basis on which the selection of the successful one, if any, was to be made. There was nothing explicit in this case, which indicated that all tenders meeting the deadline would be considered. Nevertheless:

… in the context, a reasonable invitee would understand the invitation to be saying, quite clearly, that if he submitted a timely and conforming tender it would be considered, at least if any other such tender were considered.56

By applying this test of ‘promisee objectivity’ to the circumstances, the court concluded that the defendant was in breach of an implicit unilateral contract, under which it promised that if a tender was received by the specified deadline, it would be given due consideration. The promise was not made explicitly, and indeed the defendant claimed that no such promise was intended,57 but because it was reasonable for the plaintiff to have assumed that such a promise was implied, the court found that there was a contractual relationship obliging the defendant to consider all tenders fulfilling the terms of the invitation. A person inviting tenders must therefore either explicitly state the terms on which responses will be considered, or be bound by the reasonable expectations of those who put in tenders.

This decision places some limits on the freedom of the party inviting tenders, but limits which can be avoided by careful wording of the tender documentation. Much more stringent controls exist over tendering in a range of public sector contracts as a result of European directives on the issue, which have been implemented in the UK by various sets of regulations.58 These directives are primarily intended to ensure the free working of the European market – and, in particular, to avoid nationals of the same State as the party seeking the tenders having an advantage over those based in other Member States. The controls contained in the regulations cover such matters as the way in which the tender must be publicised (for example, by being published in the EU’s Official Journal, as well as any national press), the information that must be provided, and the criteria that must be used to select the successful tender (usually based on either ‘the lowest price’ or the offer which ‘is the most economically advantageous to the contracting authority’).59 Controls of the latter kind are perhaps the most significant, in that they strike most directly at one of the main aspects of the concept of freedom of contract – that is, party freedom. The authority seeking the tenders does not have a free hand to decide with whom it wishes to contract; it must reach its decision in accordance with the regulations. It must also make clear the criteria on which its decision is based.60

There is clearly potential for the approach taken in these regulations to influence more generally the way in which tendering takes place. It would not be surprising if organisations that are required to use the European procedures in some areas of their activities found it convenient to use the same type of approach even if not constrained to do so by regulation. Such influences on business practice might in turn have an effect on the way in which the courts develop the general legal rules relating to tenders. There is no evidence to date of this happening, but the potential is clearly there.

The Sale of Goods Act 1979 makes it clear that in relation to a sale of goods by auction, the bids constitute offers which are accepted by the fall of the hammer.61 The same is also the case in relation to any other type of sale by auction.62 The normal position will be that the auctioneer will be entitled to reject any of the bids made, and will not be obliged to sell to the highest bidder.

There are two situations, however, which require special consideration. The first is where the auction sale is stated, in an advertisement or in information given to a particular bidder, to be ‘without reserve’. This situation was first considered in the nineteenth-century case of Warlow v Harrison.63 The plaintiff attended an auction of a horse that had been advertised as being ‘without reserve’. He then discovered that the owner was being allowed to bid (thus in effect allowing the owner to set a price below which he would not sell). The plaintiff refused to continue bidding and sued the auctioneer. The Court of Exchequer held that on the pleadings as entered, the plaintiff could not succeed, but expressed the view that if the case had been pleaded correctly, he would have been entitled to succeed in an action for breach of contract against the auctioneer:

We think the auctioneer who puts the property up for sale upon such a condition pledges himself that the sale shall be without reserve; or, in other words, contracts that it shall be so; and that this contract is made with the highest bona fide bidder; and, in case of breach of it, that he has a right of action against the auctioneer.64

Because of the problem over the pleadings, the ruling in Warlow v Harrison was strictly obiter, but the principle stated has now been reconsidered and confirmed in Barry v Heathcote Ball & Co (Commercial Auctions) Ltd.65

Key Case Barry v Heathcote Ball & Co (Commercial Auctions) Ltd (2001)

Facts: The claimant attended an auction to bid for two new machines that were being sold by Customs & Excise, who had instructed the auctioneer that the sale was to be ‘without reserve’. The claimant had been told this by the auctioneer when viewing the machines. The machines were worth about £14,000 each. When they came up for sale, there were no bids apart from one from the claimant, who bid £200 for each machine. The auctioneer refused to accept this, and withdrew the machines from the sale. They were subsequently sold privately for £750 each. The claimant sued the auctioneer for breach of contract. The trial judge held in his favour, on the basis of there being a collateral contract with the auctioneer to sell to the highest bidder. The claimant was awarded £27,600 damages. The defendant appealed.

Held: The Court of Appeal confirmed the decision of the trial judge. It followed the reasoning adopted by the court in Warlow v Harrison. An auctioneer who conducts a sale ‘without reserve’ is making a binding promise to sell to the highest bidder. It made no difference that in Warlow v Harrison the identity of the seller was not disclosed, whereas here it was known. Moreover, the action of the auctioneer in this situation was tantamount to bidding on behalf of the seller, which is prohibited by s 57(4) of the Sale of Goods Act 1979. The claimant was entitled to recover the difference between what he had offered and the market price of the machines. The award of £27,600 damages was therefore also confirmed.

This case is useful modern confirmation of the principle set out in Warlow v Harrison. In effect, the auctioneer is making an offer in a unilateral contract to all those who attend the auction along the lines of ‘If you are the highest bidder for a particular lot, then I promise to accept your bid’. In Warlow v Harrison, the whole auction had been advertised as being ‘without reserve’. Here the claimant had been told that this was the position as regard the particular lot in which he was interested. This made no difference to the principles to be applied.66

The second situation that requires further discussion is where a bidder tries to make a bid the value of which is dependent on a bid made by another bidder. This will only arise in a ‘sealed bid’ auction of the kind that was involved in Harvela Investments v Royal Trust of Canada.67 In this case, an invitation to two firms to submit sealed bids for a block of shares, together with a commitment to accept the highest offer, was treated as the equivalent of an auction sale. There was an obligation to sell to the highest bidder. This case was complicated, however, by the fact that one of the bids was what was described as a ‘referential bid’. That is, it was in the form of ‘C$2,100,000 or C$101,000 in excess of any other offer’. The House of Lords held that this bid was invalid and that the owner of the shares was obliged to sell to the other party, who had offered C$2,175,000.68 It reached this conclusion by trying to identify the intentions of the firm issuing the invitation to bid from the quite detailed instructions issued to each potential bidder. From these, the House deduced that what the sellers had in mind was not a true auction (where a number of bidders make and adjust their bids in response to the bids being made by others) but a ‘fixed bidding sale’. Lord Templeman noted three features of the invitation that he regarded as being consistent only with an intention to conduct a fixed bidding sale rather than an auction. First, the sellers specifically undertook to accept the highest bid. As we have seen, however, such an obligation can arise in relation to a straightforward auction, by means of a collateral contract with the auctioneer. It is hard to see this as conclusive, therefore. Lord Templeman took it, however, as also implying that the sellers were anxious to ensure that a sale resulted from the exercise. If referential bids were allowed, there was clearly a possibility that this would not happen, because both bidders might submit a referential bid, and it would be impossible to determine who was the highest bidder. The second feature noted by Lord Templeman was that the invitation was issued to two prospective buyers alone. Again, it is difficult to see this as conclusive of the issue. It is quite possible to hold a straightforward auction with only two bidders. The third feature was that the bids were to be confidential and were to remain so until the time for submission of offers had lapsed. This is by far the most convincing reason why it should be assumed that the seller intended a fixed bidding sale rather than an auction. Confidentiality of the amount of a bid is clearly incompatible with an ordinary auction (though as Lord Templeman points out later in his speech, confidential bids combined with a requirement that each bidder states a maximum bid could work as a type of auction).

In the light of all these considerations, the House of Lords concluded that it was a fixed bidding sale that was intended, and that referential bids should therefore be excluded. In effect, the House was here relying on ‘promisor objectivity’, in that its analysis is focused on what the reasonable ‘inviter of bids’ must be taken to have intended by the form in which the invitation to bid was framed. In terms of ‘offer and acceptance’, the inviter was entering into two unilateral contracts with the two bidders to the effect: ‘If you submit the highest bid, then we promise to sell the shares to you.’69

The result in Harvela was clearly of considerable practical importance: if it had gone the other way, it would have made conducting sales by means of confidential bids much more difficult. It may well be, therefore, that considerations of the impact on commercial practice helped to push the House towards the conclusion it reached.70

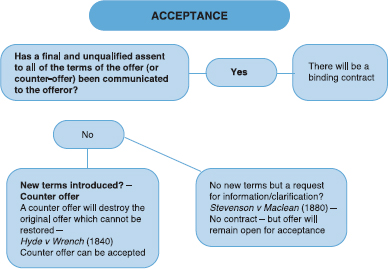

The second stage of discovering whether an agreement has been reached under classical contract theory is to look for an acceptance that matches the offer that has been made. No particular formula is required for a valid acceptance. As has been explained above, an offer must be in a form whereby a simple assent to it is sufficient to lead to a contract being formed. It is in many cases, therefore, enough for an acceptance to take the form of the person to whom the offer has been made simply saying ‘yes, I agree’. In some situations, however, particularly where there is a course of negotiations between the parties, it may become more difficult to determine precisely the point when the parties have exchanged a matching offer and acceptance. Unless they do match exactly, so the classical theory requires, there can be no contract. An ‘offer’ and an ‘acceptance’ must fit together like two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. If they are not the same, they will not slot together, and the picture will be incomplete. At times, as we shall see, the English courts have adopted a somewhat flexible approach to the need for a precise equivalence.71 Nevertheless, once it is decided that there is a match, it is as if the two pieces of the jigsaw had been previously treated with ‘superglue’, for once in position it will be very hard, if not impossible, to pull them apart.72

2.11.1 DISTINCTION FROM COUNTER OFFER

Where parties are in negotiation, the response to an offer may be for the offeree to suggest slightly (or even substantially) different terms. Such a response will not, of course, be an acceptance, since it does not match the offer, but will be a ‘counter offer’. During lengthy negotiations, many such offers and counter offers may be put on the table. Do they all remain there, available for acceptance at any stage? Or is only the last offer, or counter offer, the one that can be accepted? This issue was addressed in the following case.

Key Case Hyde v Wrench (1840)73

Facts: D offered to sell a farm to P for £1,000. P offered £900, which was rejected. P then purported to accept the offer to sell at £1,000. D refused to go through with the transaction, and P brought an action for specific performance.

The answer to the question posed above, therefore, is that only the last offer submitted survives and is available for acceptance. All earlier offers are destroyed by rejection or counter offer. The courts have not been explicit about the reasons for this rule, but it may well be that it is intended to prevent the ‘counter offeror’ having the best of both worlds – trying out a low counter offer, while at the same time keeping the original offer available for acceptance.74

It should be noted, however, that the courts will not necessarily require exact precision, if it is clear that the parties were in agreement. An example of this approach can be found in the unreported case of Pars Technology Ltd v City Link Transport Holdings Ltd,75 where the parties were negotiating the contractual settlement of an earlier dispute. The defendant offered by letter of 7 February to pay £13,500 plus a refund of the carriage charges of £7.55 plus VAT. The claimant’s letter of 12 February in response stated that the defendant’s offer to pay £13,507.55 plus VAT was accepted. The defendant later claimed that this was not a valid acceptance, because it stated that VAT was to be paid on the whole amount, rather than just on the carriage charge. The Court of Appeal agreed with the trial judge that the correspondence as a whole had to be considered, and took the view that the claimant had merely been trying to restate the defendant’s offer in a different way. The claimant’s letter had clearly stated that the defendant’s offer made in the letter of 7 February was being accepted. A contract had therefore been concluded on the terms stated in the defendant’s offer letter. In essence, the court adopted an objective approach based on what the reasonable person receiving the claimant’s letter would have taken it to mean. Even though the defendant argued that that was not what he had understood by it, he was bound by the objective view. In fact, this may be an example of the court using ‘third party objectivity’76 – that is, what would the reasonable third party looking at what passed between claimant and defendant have taken to be the outcome. It may also have been that the court was unsympathetic in this case to what it saw as the defendant using a rather technical argument to escape from an arrangement that had clearly been agreed. This is behaviour that it would not wish to encourage, because it wastes court time, and adds unnecessary costs to litigation (bearing in mind that this contract was concerned with the conclusion of an earlier legal dispute). Although it has been confirmed that under the Civil Procedure Rules, normal contractual principles applied to ‘offers to settle’ and their acceptance,77 these should not be used in a way which will have the effect of unduly prolonging the settlement of litigation.

2.11.2 REQUEST FOR INFORMATION

In some situations, however, it may be quite difficult to determine whether a particular communication is a counter offer or not. If, for example, a person offers to sell a television to another person for £100, the potential buyer may ask whether cash is required, or whether a cheque is acceptable. Such an inquiry is not a counter offer. It is not suggesting alternative terms for the contract, but attempting to clarify the way in which the contract will be performed and, in particular, whether a specific type of performance will be acceptable. The effect of an inquiry of this type was considered in Stevenson, Jaques & Co v McLean.78 D wrote to P, offering to sell some iron at a particular price, and saying that the offer would be kept open until the following Monday. On the Monday morning, P replied by telegram, saying: ‘Please wire whether you would accept 40 for delivery over two months, or if not, longest limit you could give.’ D did not reply, but sold the iron elsewhere. In the meantime, P sent a telegram accepting D’s offer. P sued for breach of contract. D argued that P’s first telegram was a counter offer, and that therefore the second telegram could not operate as an acceptance of D’s offer. The court held that it was necessary to look at both the circumstances in which P’s telegram was sent, and the form that it took. As to the first aspect, the market in iron was very uncertain, and it was not unreasonable for P to wish to clarify the position as to delivery. Moreover, as regards the form of the telegram, it did not say ‘I offer 40 for delivery over two months’, but was put as an inquiry. If it had been in the form of an offer, then Hyde v Wrench would have been applied, but since it was clearly only an inquiry, D’s original offer still survived, and P was entitled to accept it.

While the distinction being drawn here is clear, it is quite narrow. There is clearly scope in this type of situation for the courts to interpret communications in the way that appears to them best to do justice between the parties.

Figure 2.2

One situation where it may become vital to decide whether a particular communication is a counter offer or not is where there is what is frequently referred to as a ‘battle of the forms’. This arises where two companies are in negotiation and, as part of their exchanges, they send each other standard contract forms. If the two sets of forms are incompatible, as is likely to be the case, what is the result? This is a frequent occurrence, probably because under the pressure of ‘making a deal’ the parties’ attention is not focused explicitly on anything other than the most basic elements of the transaction.79