Enforcement Actions

5

Enforcement Actions

The nine most terrifying words in the English language are, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.”

President Ronald Reagan, 1911–2004

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should:

1. understand what an FAA enforcement action is;

2. have a thorough understanding of the FAA’s authority to engage in investigative activities and prosecute violations of the FARs;

3. understand the difference between an administrative and legal enforcement action;

4. have a basic understanding of the process that the FAA utilizes in determining whether to prosecute an enforcement action;

5. understand the necessary steps to protecting your interests, or your company’s interests, in the event that either is subject to enforcement proceedings.

INTRODUCTION

Chapters 2 and 3 explained that the US Constitution is the highest authority regarding the powers and limitations of the Federal Government. We have also discussed the evolution and development of the federal administrative agencies. A restricted amount of legislative, executive, and judicial authority has been delegated to such an administrative agency, the FAA, pursuant to the Federal Aviation Act of 1958. The Act transferred air safety regulation from the Civil Aeronautics Board to the new FAA, and also gave the FAA sole responsibility for a common civil-military system of air navigation and air traffic control. Accordingly, the FAA is the administrative agency responsible for promulgating, as well as enforcing, regulations related to civil aviation. The delegation of authority, through the Federal Aviation Act 1958, allows FAA inspectors, sometimes called Air Safety Inspectors (ASIs), to engage in compliance and enforcement activities. In a sense, the FAA is the judge, jury, and executioner in all matters related to civil aviation, with the exception of suspected criminal violations. The FAA refers suspected criminal offenses to the Department of Transportation Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for possible prosecution. In Chapter 9 we will explore criminal law relating to aviation.

Case 5.1 Smith v. Helms, Aviation Cases 16 Avi 18,307 (1982)

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

FACTS: Mr Smith brought suit, asking the Court to order the FAA to stop relying on its Compliance and Enforcement Program Manual FAA Order 2150.3. He alleged that the manual had policies not promulgated in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) as required by law and therefore the manual, and by extension all enforcement actions that utilized the manual, were invalid. Among other things, he sought to enjoin the FAA from using the manual until the FAA complied with the APA.

ISSUE: Is the enforcement action order relied on by the FAA (FAA Order 2150.3), in investigating and prosecuting enforcement action cases, legally valid even though the policies contained therein had never been directly published in the Federal Register as the APA requires?

HOLDING: The District Court dismissed Mr Smith’s complaint due to lack of standing and never directly addressed the issue regarding the legal validity of Order 2150.3. However, the Court analyzed the FAA’s regulatory framework in the body of its decision and determined that numerous FAA orders (in addition to orders in certificate actions) had undergone direct review and had withstood scrutiny by various courts of appeals as provided for in section 1006 of the APA. Furthermore, the Court determined that the enforcement procedures implementing the FAA’s statutory provisions are published in 14 CFR Part 13 and that these regulations constitute rules published and adopted in accordance with the APA.

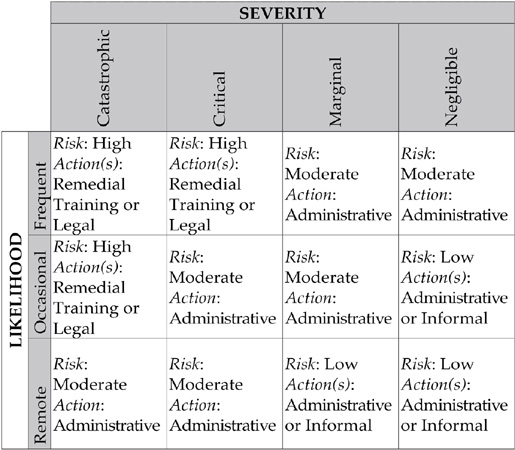

An FAA enforcement action is an administrative action taken against a certificate holder for alleged violations of the FARs. The FAA utilizes statutes, regulations, and internal administrative orders in the investigation and prosecution of enforcement actions. FAA Order 2150.3B is the internal administrative order containing the policies, procedures, and guidelines used by the FAA regarding compliance and enforcement actions.1 This order also articulates the FAA’s philosophy for using various remedies, including education, corrective action, remedial training, informal action, administrative action, and legal enforcement action in addressing alleged noncompliance with statutory and regulatory requirements. FAA inspectors also follow procedures in FAA Order 8900.1 in determining what type of action (legal, administrative, or informal) to take against an alleged violator.

The initiation of the compliance and enforcement process typically comes about as the result of routine surveillance or inspection, public complaints, accident and incident investigations, or reports from air traffic controllers. Controllers and Managers from the FAA’s Air Traffic Organization (ATO) often use the term “pilot deviation” when referring to potential violations of the FARs leading to an enforcement action.

The FAA’s compliance and enforcement method of investigation may eventually lead to an Enforcement Investigative Report (EIR) that is used to substantiate any contemplated enforcement action. The EIR process is outlined in FAA Orders 2150.3 and 8900.1. The Enforcement Decision Process (EDP) is an analytical system used by FAA inspectors to assist in determining the appropriate recommended action for a suspected violation of the FARs. It was developed with the avowed purpose of matching the safety risk posed by an alleged act with the type of conduct involved.

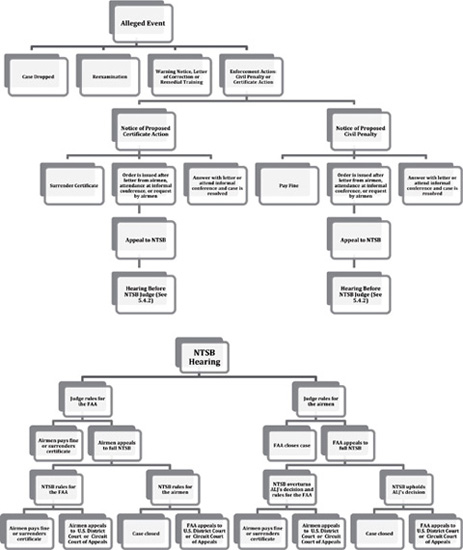

THE “TYPICAL” ENFORCEMENT ACTION CASE

The steps involved in enforcement actions vary on the party or entity under investigation and the remedy sought by the FAA. The typical certificate action against a pilot for an alleged violation of the FARs involves the steps below. Although each of these steps will be reviewed in greater detail throughout this chapter, a general overview should be helpful as the process can be complicated. Comments following the FAA’s typical actions include suggested responses by the pilot under investigation.

Keep in mind that the sample scenario below is meant to illustrate a typical FAA enforcement action against a pilot and is not intended to be legal advice. Depending on the nature and/or severity of the event, it may be advisable to seek aviation legal counsel that is intimately familiar with the enforcement action procedure prior to taking any action. An enforcement action typically involves the following actions.

First, the pilot is notified by an air traffic control facility (enroute, terminal radar approach control, or tower) of a possible incident that could lead to an enforcement action. This advisory of a possible pilot deviation notification is called a Brasher Notification. You will know if you are the subject of a potential enforcement action if an air traffic controller gives you a number to call when reaching, or en route to, the destination airport. You are not required by the FARs to make the call to the air traffic facility. In the past, in situations that did not involve serious matters, other aircraft, or restricted airspace, a phone call combined with a compliant attitude often put the matter to rest immediately. This, however, is no longer the case. With the evolution of the ATO’s “just culture/learning culture,” the failure by an FAA employee to report and document a possible pilot deviation could lead to the employee being disciplined. For this reason, controllers and ATO Managers no longer have any latitude to deal directly with minor violations and mitigate the event via a training discussion on the telephone. Moreover, in the past, if the event was going to be processed by the FAA, air traffic controllers were required to submit preliminary pilot deviation information to the FSDO within 12 hours of the occurrence and a final report within 10 days. Now these reports are submitted within minutes via an electronic Mandatory Occurrence Report (MOR), which is generated as soon as the supervisor or controller-in-charge makes the entry into the daily facility operations log. Therefore, in most cases the MOR has already been generated and transmitted before the pilot has even had the opportunity to call the facility as instructed in the Brasher Notification. There is no longer any advantage whatsoever for pilots to discuss the incident with air traffic control (ATC) personnel. Therefore, the telephone discussion should be limited to providing the supervisor or controller in charge with the pilot’s name, address, telephone number, and certificate number. Pilots should not make any statements regarding the incident as that may very well undermine their legal position in the future. Lawyers call such statements “admissions against interest.” In the event that you decide to call the FAA facility, you must keep in mind that your conversation will be recorded, included as a part of the investigation package submission, and used against the pilot if the pilot admits to any potential violation.

Prior to calling the FAA, the pilot should immediately review NTSB Part 830 to determine if they were involved in an “Incident” or “Accident.”2 Optimally this will be done before contacting the FAA facility. If you are involved in an incident, file a NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) Form 277 in a timely manner, if appropriate.3 Take this action within 10 days of the incident. Electronic filing is preferred, yet they are accepted via regular mail. Make sure that you have proof that the form was filed within the 10-day period. There are some exceptions to this suggestion.4 If you are involved in an accident, you should seek legal assistance prior to giving any substantive interview to the FAA or the NTSB. While NTSB Part 830.5 requires that you contact an NTSB field office “immediately, and by the most expeditious means available,” do not file an NTSB Form 6020.1, NASA ASRS Form 277, or divulge detailed information reference Part 830.6(h) (regarding the nature of the accident) prior to consulting with a qualified aviation attorney. In the event of an accident, the data in NASA Form 277 will not be confidential.5

Once a MOR has been electronically generated by an air traffic facility, it is first transmitted to one of three ATO Service Centers in Seattle, Dallas, or Atlanta for initial vetting by ATO Quality Assurance/Control staff. In the past, this initial vetting took place at the Air Traffic Control facility itself by staff specialists and managers who are, or have been, certified on the positions involved. This action ensured that causal factors where air traffic was contributory were identified quickly, such as hearback/readback errors, misapplication of ATC procedures, use of non-standard ATC phraseology, or general poor performance by air traffic controllers. Often, this resulted in a decision not to refer the suspected pilot deviation to the FSDO or, in the case of Air Carrier Aircraft, the Certificate Management Office (CMO). Unfortunately, under the new process which became effective on January 30, 2012, the initial vetting of a pilot deviation is now conducted by personnel who often lack the requisite experience to conduct an adequate review of the incident. For example, it is not at all uncommon that an FAA employee with no ATC experience is the one responsible for screening the alleged violation to determine whether a regulation has been violated. As a result, suspected pilot deviations with considerable ATC culpability, shared liability, or events that are not pilot deviations at all now continue to the FSDO/CMO referral process due to the lack of any effective ATO investigatory capability. In summary, air traffic field facilities no longer make the determination whether a particular MOR constitutes a pilot deviation; in fact, there is no requirement for a field facility to review the recorded transmissions or the RADAR replay/plot data, as was the requirement in the past. The determination of whether any particular MOR constitutes a pilot deviation is now made solely at the ATO Service Center level. This sometimes leads to unjust results.

Next, an airman will eventually receive a Letter Of Investigation (LOI). Once the FAA begins an investigation, the FAA FSDO inspector will send out a form letter, such as that shown in Figure 5.6, notifying the pilot that if he or she does not respond within 10 days, the FAA’s report will be processed without the benefit of the recipient’s comments. As with recorded conversations with ATC facilities, any response to this letter will be treated as an admission against your interest.6 You are not required by the FARs or the law, as recently modified by the Pilots’ Bill of Rights (PBR), to respond to this letter.7 Failing to respond will not result in a negative inference against an airman. You should only respond if you have irrefutable evidence that you did not commit violations of the FARs. Unless you have exculpatory evidence (evidence that is favorable to you), you should wait for the “Informal Conference” to explain his or her story, including any factors that would tend to persuade the FAA not to undertake formal action.

The FAA will wait for a short period of time and will then determine its initial course of action. The FAA defines informal actions as verbal or written counseling of individuals or entities. Administrative actions are Letters of Correction or Warning Notices. An informal or administrative action stays on the airman’s record for two years. These are issued if the matter is minor and not intentional.8 Considering the other possibilities, this is by far the best outcome. A legal enforcement action may take the form of certificate revocation, suspension, or the assessment of monetary penalties. It will remain on the airman’s record for at least five years.9 Clear violations of the FARs will almost certainly lead to an initial determination that an enforcement action is necessary. The FAA is required to follow FAA Orders 2150.3 and 8900.1 in determining which action to take. A Notice of Proposed Certificate Action or a Civil Penalty Assessment is used by the FAA to notify a suspected violator that a legal enforcement action is being sought. Once a pilot receives this, several options exist:

1. Request an “Informal Conference.”10 This is the preferred course of action and prior to attending, the airman should seek the FAA’s EIR utilizing a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. In addition, the PBR also requires the FAA to provide the airman access to data in the possession of the FAA that would facilitate the individual’s ability to productively participate in the FAA’s investigation. Both FOIA and PBR requests should be made, and data reviewed, prior to the informal conference. The informal conference is an attempt to settle the case by reducing or eliminating the sanction. Contradictory statements made during such “informal” proceedings can be used against the pilot in any subsequent proceedings, such as a hearing before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ).

2. Write a letter of explanation. Anything in this letter is subject to being used against the airman’s interest and therefore, as mentioned throughout this chapter, such a course of action is rarely suggested or successful.

4. Pay the civil fine. In the event that the FAA is attempting to assess a civil penalty, an airman may admit to the infraction and paying a set amount of money to the US government.

In conjunction with an enforcement action case, the FAA will often request a re-examination.11 A re-examination is not an enforcement action and the FAA can take this action anytime it has “reasonable cause” to do so. An airman must comply or may have his or her privileges revoked. Pilots are required to pay for this. Successfully passing the re-examination does not mean that the FAA will not assert an enforcement action. Therefore, the pilot should never discuss the facts or circumstances regarding the incident leading to the re-examination during the re-examination itself.

An airman may continue operating according to his or her certificate until an Order of Suspension, Revocation or Civil Penalty is assessed. These are effective immediately if a requested informal conference is unsuccessful and a timely appeal is not filed. Filing an appeal stays non-emergency orders, allowing pilots to continue flying pending the appeal process. Keep in mind that emergency orders must be appealed within 48 hours.

In order to get a formal hearing before the NTSB, the airman must file an appeal. Once a pilot appeals the FAA’s determination, the FAA files a “Complaint.” Usually this Complaint is a cover letter stating that the Order of Suspension serves as the Complaint. The pilot/respondent must then file an Answer in a timely manner.12 The Hearing occurs before an NTSB ALJ.13 This is the only step in the process where the pilot gets to present his or her case through evidence and witnesses before a judge. There is no jury.

If either party is not satisfied with the ALJ’s determination after the hearing, the next level of appeal is to the entire NTSB. In almost all cases the appeal only involves the hearing judge’s application of the law to the facts. At this stage, you do not have another opportunity to present evidence or witnesses (deemed a “de novo” review). The full board’s determination is made after considering the written legal positions (called “briefs”) of the parties. The full board will not over-rule the ALJ’s decision unless the full board finds as a matter of law that the ALJ’s decision was arbitrary or capricious.14

Judicial Review

If either party is not satisfied with the full board’s final order, the next level of appeal is to either a Federal District Court or the US Court of Appeals. As the PBR is a relatively new statute, there is a question of whether an appeal to a District Court would effectively grant an airman a new, or de novo, hearing. The PBR states that a District Court shall give “full independent review” of a denial, suspension, or revocation of an airman’s certificate. At the time of publication, only one court has addressed the issue of what a full independent review means.15 In the Dustman case, the court held that the standard and scope of District Court review is in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act. As such, appeals to the Northern Illinois District Court will result in review of the administrative record only; that is, appellants in this District will not receive a de novo review. As the law currently stands, the parties file written briefs with the court. Again, there is no opportunity to present witnesses or evidence. Oral argument may be asked for, yet it is discretionary by the court. The court must find as a matter of law that the NTSB’s decision on appeal was arbitrary or capricious in order to over-rule the NTSB’s decision.16 As a practical matter, this is very difficult to achieve. Therefore, the vast majority of NTSB decisions are not overturned on appeal. Technically another level of appeal is available to the US Supreme Court via writ of certiorari. However, it is highly unlikely that the court would exercise jurisdiction. At least four of the nine Justices of the Supreme Court must agree to grant the petition for certiorari. A petition for certiorari is granted in a small number of select cases numbering less than 100 per year. The court has never accepted an enforcement case for review.

Keep in mind that the enforcement action process varies depending on the person or entity alleged to have violated an FAR and the amount or type of sanction sought by the FAA. For example, in a case where the penalty sought exceeds $50,000 or is against an airline or other entity, an ALJ does not hear the case. In the event that the charged party cannot settle the matter with the FAA in a case where the amount sought exceeds $50,000, the FAA refers the suit to the Department of Justice, which brings suit in the appropriate District Court in order to enforce the FAA’s proposed civil penalty order. In addition, if the FAA believes that a military pilot has violated a FAR, it refers the matter to the Department of Defense. Alleged violations by foreign pilots are referred to the State Department. Most of these scenarios, depending on the specific party and type of enforcement action, will be explored in detail throughout this chapter.

TYPES OF ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS

To enforce suspected violations of civil regulations and statutes, the FAA has various courses of actions available. These include informal action, administrative action, and legal enforcement actions as outlined above. The FAA has very broad authority in determining which type of action to pursue against suspected FAR violators.

Case 5.2 Go Leasing, Inc. v. National Transportation Safety Board, 800 F.2d 1514 (1986)

United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit

FACTS: Go Leasing, Inc. was one of three affiliated aviation companies, each of which held an individual FAA operating certificate. Go Leasing held a Part 125 certificate. According to 14 CFR Part 125: “No certificate holder may conduct any operation which results directly or indirectly from any person’s holding out to the public to furnish transportation.” Such operations require a Part 121 air carrier certificate. The FAA conducted an inspection of Go Leasing as well as its affiliated companies and discovered FAR violations. The FAA issued an emergency order revoking the operating certificate of Go Leasing as well as the certificate of each affiliated company. Go Leasing sought an expedited hearing according to 49 CFR §§821.54–821.57. The ALJ affirmed the FAA’s emergency order, with slight modification, and Go Leasing appealed the ALJ’s decision to the full NTSB. The full Board affirmed the emergency order. Go then appealed the Board’s decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

ISSUE: Does the FAA have discretion in determining whether to levy a civil penalty or certificate action, or can the alleged violator choose among potential remedies?

HOLDING: The Court of Appeals held that “there is no question that the Administrator has the legal discretion to choose between employing section 609 [of the Federal Aviation Act] certificate action and section 901 civil money penalty remedies.” The Court upheld the Administrator’s scope of discretion in selecting from among statutory remedies and also held that alleged violators have no right to dispute the FAA’s determination.

Administrative and Informal Actions

Administrative actions are governed by 14 CFR §13.11. These “informal” actions are those in which the FAA provides either verbal or written counseling and is often taken by the FAA in incidents with a low safety risk where an individual was careless or a business unintentionally violated an FAR. Administrative actions do not result in a finding of violation or the imposition of a sanction (i.e. a civil penalty). Such actions consist of the Warning Notices or Letters of Correction first discussed above. A Warning Notice is a letter or form that is issued to bring the facts and circumstances to the attention of an alleged violator. It advises that, based on the available information, the alleged violator’s action or inaction appears to be contrary to the regulations, but does not warrant legal enforcement action. A Warning Notice typically contains the date of the notice, Enforcement Investigative Report number, date the alleged violation occurred, name of the alleged violator, description of the incident and the specific regulations allegedly violated, a statement that the matter does not warrant legal enforcement action, and an opportunity for the alleged violator to respond to the allegation. Figure 5.1 below contains an example of a Warning Notice. Informal actions are those in which the FAA provides either verbal or written counseling and are often taken by the FAA in incidents with a low safety risk where an individual was careless or a business unintentionally violated an FAR.

A Letter of Correction serves the same purpose as a Warning Notice, but is used when there is agreement with the company, organization, or airman that corrective action acceptable to the FAA has been taken or will be taken within a reasonable amount of time. It is also used when the FAA determines that remedial training is appropriate instead of more formal action. The Letter of Correction contains all of the information contained in the Warning Notice and also a description of the action that has, or will, be taken. Figure 5.2 is an example of a Letter of Correction.

Neither a Letter of Correction or Warning Notice constitutes a finding of a violation, therefore a notice and hearing are not required, and neither one may be considered part of the person’s formal violation history. However, an administrative record of the Letter of Correction or Warning Notice is kept as part of the airman’s record for two years before expungement. Participation in the FAA’s Voluntary Disclosure Reporting Program, the remedial training program, and the Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP) may result in the issuance of an administrative action in lieu of a legal enforcement action. With the administrative enforcement actions, airmen have no appeal rights.

CERTIFIED MAIL – RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED

August 28, 2014

EIR Number: 2014WP000100

Mr. Hank Smithers

1075 Victory Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90009

Dear Mr. Smithers:

On May 26, 2014, you were the pilot-in-command of a Beech Baron N2345 that landed at the City Airport. At the time of your flight, it appears that you did not have a pilot certificate or photo identification in your possession or readily accessible to you in the aircraft. This conduct is allegedly in violation of 14 CFR 61.3(a).

After a discussion with you concerning this matter, we have concluded that the matter does not warrant legal enforcement action. In lieu of such action, we are issuing this letter which will be made a matter of record for a period of two years, after which, the record of this matter will be expunged.

If you wish to add any information in explanation or mitigation, please write me at the above address. We expect your future compliance with the regulations.

Sincerely,

I.M. Agovguy

Aviation Safety Inspector

Attachment: Privacy Act Notice

Figure 5.1 Sample warning notice

CERTIFIED MAIL-RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED

December 26, 2014

EIR Number: 2014WP000200

ACME Repair Station Company

Attention: Mr. Alan Smith, President

3665 East Van Buren Street

Phoenix, Arizona 85034

Dear Mr. Smith:

From December 14–18, 2014, the Federal Aviation Administration inspected your repair station’s organization, systems, facilities, and procedures for compliance with 14 CFR part 145. At the end of that inspection, we advised you of the following findings:

[FAA places findings here].

This is to confirm our discussion with you on December 18, 2014, at which time immediate corrective action was begun.

[Corrective action taken stated here].

We have considered all the available facts and concluded that this matter does not warrant legal enforcement action. In lieu of such action, we are issuing this letter of correction which will be made a matter of record.

Sincerely,

I.M. Agovguy

Aviation Safety Inspector

Figure 5.2 Sample letter of correction

CERTIFIED MAIL – RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED

September 23, 2014

FILE NO. 2014WP000300

Mr. John D. Smith

1711 Colorado Avenue

Phoenix, Arizona 85034

Dear Mr. Smith:

On September 12, 2014, you were advised that the Federal Aviation Administration was investigating an incident that occurred on September 5, 2009 in the vicinity of Phoenix, Arizona and involved your operation of a Cirrus SR-22, N12345.

You have been advised and have acknowledged that such an operation is contrary to Section 91.123 (a) of the Federal Aviation Regulations. Therefore, you have agreed to enter into this training agreement.

In consideration of all available facts and circumstances, we have determined that remedial training as a substitute for legal enforcement action is appropriate. Accordingly, your signature on this letter signifies your agreement to complete the prescribed course of remedial training within the assigned period of time. To complete this remedial training program successfully you must do the following:

a. You must obtain the required training from an approved source. Approval can be obtained verbally from this Flight Standards District Office, upon obtaining the services of a certified flight instructor.

b. Once training begins, you are required to make periodic progress reports to this office.

c. You are required to complete all elements of the remedial training syllabus and meet acceptable completion standards within 21 days of accepting this training agreement.

d. You are required to provide this office with written documentation indicating satisfactory completion of the prescribed remedial training. You must provide the original of a written certification signed by the certified flight instructor who conducts the remedial training. The written certification must describe each element of the syllabus for which instruction was given and the level of proficiency you have achieved.

e. All expenses incurred for the prescribed training must be borne by you.

REMEDIAL TRAINING SYLLABUS

Syllabus Objective: To improve the student’s knowledge and pilot proficiency concerning proper use of the SR-22 flight director, navigation and autopilot avionics systems specific to N12345.

Syllabus Content:

a. A minimum of two hours of ground instruction on the following subjects:

1. Compliance with ATC clearances

2. Programming and use of the GNS 430 navigation system for IFR operations

3. Use of the autopilot for IFR operations

b. A minimum of one hour of flight instruction in IFR procedures to include:

1. Compliance with IFR clearances

2. Use of the GNS 430 navigation system and the autopilot for IFR departures and arrivals

3. Timely response to undesired autopilot commands

Completion standards: The training will have been successfully completed when the assigned instructor, by oral testing and practical demonstration, certifies that the student has completed instruction in the above-mentioned subjects in accordance with the remedial training syllabus.

____________________ | ___________ |

John L. Doe | Date |

Aviation Safety Inspector |

|

Figure 5.3 Remedial training letter and syllabus

REMEDIAL TRAINING

FAA inspectors often offer remedial training to an airman when appropriate. Remedial training is a form of FAA administrative corrective action that uses education as a tool to allow airmen who have committed an inadvertent violation to increase their knowledge and skills in areas related to the violation. Remedial training applies to an individual certificate holder who was not using his or her certificate in air transportation for compensation or hire at the time of the apparent violation. The FAA may therefore offer remedial training when:17

1. the alleged act was not deliberate, e.g. repeated buzzing of a house as opposed to an inadvertent deviation from minimum safe altitudes because of unforecasted weather;

2. the noncompliance with the FAR was not the cause of an accident;

3. the noncompliance did not actually compromise safety, i.e. created a condition that was significantly unsafe;

4. the noncompliance did not indicate a lack of qualification, which would require re-examination, on the airman’s part;

5. the noncompliance was not caused by gross negligence;

6. the noncompliance was not of a criminal nature;

7. the airman exhibits a constructive attitude toward safety and is deemed not to be likely to commit acts of noncompliance in the future; and, as mentioned above,

8. the airman was not using his or her certificate in air transportation for compensation or hire at the time of the apparent violation.

Furthermore, the inspector will review the airman’s enforcement history and evaluate whether that history supports or precludes participation in the remedial training program. Ideally, the FAA prefers that candidates are first-time “offenders”; however, previous enforcement history does not automatically exclude an airman from the program.

The investigating aviation safety inspector (or any other FAA personnel) will not conduct the training. The inspector, based on the facts of the case, simply recommends whether or not he believes that the airman under investigation is eligible for remedial training. The inspector makes this recommendation to the FSDO Accident Prevention Specialist (APS) (or other qualified person designated at the discretion of the FAA district office manager), who is then responsible for interviewing the airman and designing, implementing, and monitoring a program specific to the airman and the compliance issue. The remedial instructor is usually appointed by the FSDO. The instructor’s fee is at the airman’s expense. Typically, the FAA attaches a syllabus to the letter outlining the specific training program. A sample Remedial Training Agreement and Syllabus is provided in Figure 5.3. Usually a minimum of three hours of ground school and three hours of flight training is required. At times the program requires visits to and monitoring of air traffic control facilities. The airman must complete any agreed-upon remedial training within 120 days of the FAA becoming aware of the violation. Adverse weather conditions, unavailability of equipment, airman illness, etc. are conditions for extending the remedial training period; however, the inspector must consider 49 CFR, §§821 and 821.33, the NTSB’s stale complaint rule (discussed below), prior to extending the remedial training deadline. Remedial training is not re-examination and therefore there is no testing component to the program. Failure to complete the training within the time specified results in the termination of the airman’s participation in the program. The inspector will then initiate a legal enforcement action.18

After the airman completes the training program and provides evidence to that effect to the APS, the APS then indicates to the investigating inspector the successful completion of the training. Based on that information, the inspector issues a Letter of Correction documenting that the terms and conditions of the remedial training were met, concludes the case, and closes out the Enforcement Investigation Report. The airman’s record will reflect that he or she was the subject of FAA administrative action, yet there will be no violation in the airman’s records. Alleged FAR violations by airman and companies not resolved by remedial training usually result in certificate actions (against airman) and civil penalties (against companies).

Legal Enforcement Actions

Certificate Actions

Legal enforcement actions are the most serious action that the FAA can pursue against a pilot. These result in certificate actions or assessment of civil penalties (fines). Procedures for such actions are set forth starting at 14 CFR §13.13. The FAA has the burden of proof in prosecuting certificate actions and civil penalties. This means that the FAA is obligated to prove each element of any alleged FAR violation. However, the standard is the relatively low preponderance of the evidence. This means that the FAA only has to offer enough evidence to show that its claim that a certificate holder has violated the FARs is more likely to be true than not.

Certificate action refers to situations in which the FAA is attempting to suspend or revoke an airman’s certificate according to the guidelines set forth in 14 CFR §13.19. In general the FAA chooses certificate actions over fines for individuals and vice versa for business entities. The FAA may bring a civil penalty action against an airman to avoid the stale complaint rule. This rule requires the FAA to initiate a certificate action within six months. There is a two-year limitation regarding civil penalties. They also tend to choose certificate actions when the alleged violation was operational versus an administrative or record keeping issue. The FAA’s stated purpose regarding certificate suspensions for a fixed number of days is to punish alleged violators and deter others from committing a future violation. Suspensions of indefinite duration are issued to prevent a certificate holder from exercising privileges pending demonstration that the airman meets the standards required to hold his or her certificate. Certificate revocations are issued when the FAA determines that a holder is no longer qualified to hold the specific certificate. Some revocation examples include:

• a pilot operating an aircraft under the influence of alcohol;

• a pilot intentionally falsifying a document; or

• a felony drug conviction of a flight crewmember using an aircraft in the commission of the offense.

Certificate holders have very limited direct recourse against the actions of an FAA aviation safety inspector. Inspectors have broad authority and are immune from personal liability for common law torts committed within the scope of their employment. However, immunity does not apply to interference with constitutional rights. Such rights ultimately affect how the FAA conducts its compliance and enforcement program. For example, the US Constitution provides that a person is afforded due process of law (i.e. the FAA must tell the person what he or she did wrong and give the person a chance to answer the charges) and a reasonable expectation of privacy (e.g. an inspector cannot enter private property, including private aircraft, without the owner’s permission).

Legal enforcement actions by the FAA can remain on your record indefinitely (revocations) or for a period exceeding five years (suspensions or civil penalties). With legal enforcement actions, airmen have extensive appellate rights. The typical progression of an enforcement action where the FAA is seeking to take a certificate action against a pilot was outlined above. In summary, the certificate action process involves notification by the FAA via a letter of investigation, the investigation, issuance of a notice of a proposed certificate action, participation in an informal conference, issuance of an order of suspension or revocation, appeal of the order, a hearing before an ALJ, appeal to the full NTSB, appeal to a District Court, and appeal to the US Circuit Court of Appeals. The civil penalty process is similar, yet the steps vary depending on the party and the amount of the fine that the FAA is seeking.

Civil Penalties

FAA civil penalty proceedings are governed by the Rules of Practice, 14 CFR §13.16 et seq and Part 13, subpart G (§§13.201–13.235). The FAA uses these penalties as punishment for certain statutory or regulatory violations. The punishment, which involves a monetary payment or fine, is intended to penalize noncompliance and deter future violations. The fines differ in amounts depending on the party charged with the alleged enforcement action. Civil penalties are often charged for administrative errors, such as incorrect or poor record-keeping, or when the alleged violator is an entity such as an airline. Penalties exceeding $50,000 most often pertain to airlines and other types of business entities. Pilots, mechanics, repairmen, and flight engineers (collectively in this section referred to as airmen) are usually subject to fines of less than $50,000. Airmen may be fined up to $1,100 for each violation, business entities and operators of airports up to $11,000 for each violation, and each falsification of documents violation up to $250,000 regardless of whether the party is a business or individual. There is no $50,000 limitation on assessments for violations of the Hazardous Materials Transportation Safety Act or the Hazardous Materials Transportation Regulations, and the penalty for each violation of these requirements ranges from $250 to $27,000.

As discussed above, in most cases the FAA will seek to prosecute a certificate action against individuals and a civil penalty action against business entities such as an airline. However, in cases of intentional malfeasance, the FAA may seek to revoke or suspend the entity’s certificate. The administrative or judicial process depends on whether the FAA is bringing an enforcement action with a proposed civil penalty against an airman, non-airman, or a business entity, and the amount of the proposed fine.

Civil Penalty Action: Fine of $50,000 or Less Against a Certificate Holder The civil penalty action process starts when the certificate holder is notified by the FAA that they are suspected of violating a FAR, the maximum fine allowable, and often an offer to settle the claim for less than the maximum penalty in order to induce settlement and acceptance of the proposed penalty. Most often the airman will not be offered an informal conference, yet can request one. In the event that the proposed action is not settled, the FAA will go ahead and issue an order assessing civil penalty pursuant to 14 CFR §13.18. The airman then appeals this proposed order and the process is the same as for a typical airman certificate action. In other words, the hearing will be before an NTSB administrative law judge, an appeal to the full NTSB, and a further appeal to the US Circuit Court of Appeals.

Civil Penalty Action: Fine of $50,000 or Less Against a Person Who is Not an Airman According to 14 CFR §13.16, the FAA may impose a civil penalty against a person other than an individual acting as a pilot, flight engineer, mechanic, or repairman, (i.e., not an airman) after notice and an opportunity for a hearing on the record, for violations cited in 49 U.S.C. 46301 or 47531. As these individuals do not posses FAA certificates, the only penalty the FAA can impose is a civil fine. These violations in general involve aviation safety issues and noise abatement. Also, any person (regardless of their status) that who the federal hazardous materials transportation law, 49 U.S.C. Chapter 51, or any of its implementing regulations may be prosecuted under 14 CFR §13.16.

These matters are prosecuted by the FAA in accordance with rules found in 14 CFR §13.201. The administrative law judge that hears these cases is employed by the Department of Transportation and not the NTSB. In the event that a settlement cannot be reached, an administrative trial is held where the FAA must prove the alleged violation using the preponderance of evidence standard. Whereas in a formal certificate action case against an airman the full NTSB decides appeals, the Administrator of the FAA serves as decision maker regarding civil penalty case appeals against non-airmen. The FAA’s Adjudication Branch and Assistant Chief Counsel advise and in actuality make decisions on behalf of the Administrator. To ensure that this process operates fairly and in accordance with the APA,19 the FAA has issued rules requiring a separation of the functions performed by the agency attorneys who prosecute civil penalty actions, and attorneys who advise the Administrator on appeals from initial decisions. The intention in separating these functions is to insulate the Administrator from any advice or influence by an FAA employee engaged in the investigation or prosecution of civil penalty actions. It also insulates the prosecutors from possible influence by the advisers to the Administrator on appeals.

If a party disagrees with the FAA’s decision, they can ask the Administrator to reconsider his or her decision and/or process a further appeal with the appropriate US Court of Appeals. Judicial review is in the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit or the US Court of Appeals for the circuit in which the party resides or has the party’s principal place of business. In these “non-airman” cases, the NTSB does not play a role.

Civil Penalty: Amount of Proposed Fine Exceeds $50,000

The FAA uses procedures found in 14 CFR §13.15 when the proposed fine is greater than $50,000 against an individual or small business concern or in excess of $400,000 against an entity other than an individual or small business concern, it seeks to seize an aircraft subject to a lien, it seeks injunctive relief (which means a person or entity is ordered to do or refrain from doing a certain act), or it wants to enforce an unpaid civil fine.20 An air transportation small business concern is defined according to the number of employees or annual revenue.21 Businesses that do not qualify as a small business concern, such as major airlines, can be fined up to $400,000 using the administrative assessment procedures found in 14 CFR §13.16, as discussed above.

Figure 5.4 Enforcement action flowcharts

It has not been possible to amend this figure for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472445629Figure5_4.pdf

In these matters, the FAA refers the case to the Department of Justice, asking it to file suit on behalf of the Administration if a compromise cannot be reached. These cases are filed and processed like any other civil lawsuit. The suit is filed in the proper US District Court and a federal judge hears the case. Unlike the administrative proceedings discussed above, the accused defendant can demand a jury trial. A formal trial is held using the Federal Court Rules of Civil Procedure and Evidence. A party who wants to appeal the decision of the trial court appeals the case to the proper US Court of Appeals. Further appeal to the Supreme Court is optional, not mandatory, and is highly unlikely to be granted. The various types of formal enforcement actions and litigation processes are summarized in Figure 5.4.

The FAA’s Power to Interpret the Regulations

Prior to the enactment of the PBR, the NTSB was bound by regulations validly promulgated by the FAA with regard to the interpretations of the rules and regulations adopted by the Administrator. Until the Garvey case, outlined in Case 5.3, basic due process concerns required prior notice through precedent or rule making. Airmen are assured due process in regards to the FARs because the rules are issued via the administrative rule-making process that requires notice and an opportunity to give feedback on the rule prior to adoption. The rule-making process includes prior notice and an opportunity to comment on the propriety of the proposed rule. After the Garvey case and prior to the PBR, the prevailing law allowed FAA attorneys to advise the NTSB of FAR interpretations during the litigation process. Since the NTSB was required to follow FAA interpretations of the FARs, this effectively gives the FAA authority to disregard established precedent during litigation. The PBR eliminated the special deference that the NTSB was required to give the FAA regarding the FAA’s interpretation of its regulations. The NTSB now follows the Chevron standard of deference with regard to the FAA’s interpretation of its own regulations. Great deference is still given to the FAA in administrative hearings and airmen have a right to be concerned. Government power, if misused, may lead to unjust results. As former President Reagan once said, “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.’”22

Case 5.3 Garvey v. National Transp. Safety Bd., 190 F.3d 571 (1999)

United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit

FACTS: Captain Richard L. Merrell was the pilot in command of a Northwest Airlines Flight departing Los Angeles in June 1994. An air traffic controller cleared Captain Merrell to climb and maintain 17,000 feet. Captain Merrell read back the clearance correctly. Approximately one minute later, the controller instructed an American Airlines Flight to climb to and maintain flight level 230 (23,000 feet). The American Airlines captain correctly read back the clearance. The Northwest Flight was numbered 1024. The American Airlines flight was numbered 94. Captain Merrell heard the climb clearance issued to the American Airlines flight 94, yet believed it was directed to his Northwest flight 1024. He read back the 23,000-foot climb instruction to the air traffic controller believing it was issued to his flight. At the time that he read back the clearance, the American pilot also read back the clearance. Merrell started to climb, violating the clearance he was issued. The FAA processed an enforcement action for “inattentive carelessness” in violation of 14 CFR section 91.123(b) (operating contrary to an ATC instruction) and 14 CFR section 91.123(e) (following a clearance issued to another pilot). Merrell appealed the FAA order to the NTSB and therefore was afforded a hearing. The NTSB ALJ agreed with the FAA at the hearing and affirmed the FAA Order. Merrell then appealed the ALJ’s decision to the full NTSB. The Board found that Merrell had made an error of perception, yet also decided that he was not performing his duties in a careless or otherwise unprofessional manner and reversed the ALJ, thereby exonerating him. The full Board reasoned that Merrell had made a full readback of the clearance, although it wasn’t meant for his flight, and that mistakes of this kind was not always the result of careless inattention. If it weren’t for the “blocked” transmission, the misunderstanding would have been discovered and corrected by the air traffic controller. The FAA appealed the full Board’s holding to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.