Enforcement

ENFORCEMENT

(1) Overview

7.01 This chapter considers the enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision by way of court proceedings, usually by following the special procedures developed by the Technology and Construction Court (TCC). It also considers other potential enforcement procedures such as injunctions, declaratory relief, winding-up orders, and final charging orders. It deals with enforcement of part but not all of an adjudicator’s decision and reviews the law of severability in this regard; discusses approbation and reprobation, costs and interest, and enforcing the judgment of the court.

7.02 This chapter does not attempt to deal with every case on enforcement, but rather the key cases or cases that illustrate the courts’ application of the principles of enforcement. The specific challenges that may be made to resist enforcement of a decision are considered in Chapters 9 to 11.

(2) General Principles of Enforcement

Valid Decisions Should Be Summarily Enforced

7.03 Since the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’) came into effect in 1998, the High Court and Court of Appeal have repeatedly emphasized the special character of adjudicators’ decisions and the policy considerations underpinning s. 108 of the 1996 Act. The adjudication process is recognized as a ‘speedy mechanism for settling disputes in construction contracts on a provisional interim basis, and requiring the decisions of adjudicators to be enforced pending the final determination’.1 Summary judgment should be entered to enforce adjudicators’ decisions, and if the decision is wrong, it can be corrected in subsequent court or arbitral proceedings.2 Adjudicators’ decisions are therefore generally summarily enforced without deduction, set-off, withholding, reliance on a cross-claim, abatement, or stay of execution.3

7.04 An adjudicator’s decision does not involve the final determination of the parties’ rights4 and as a result the courts seek to enforce decisions wherever possible. However, only valid decisions must be enforced. Thus, while some may refer to the ‘right of enforcement’, this is qualified or contingent upon the validity of the decision itself.5

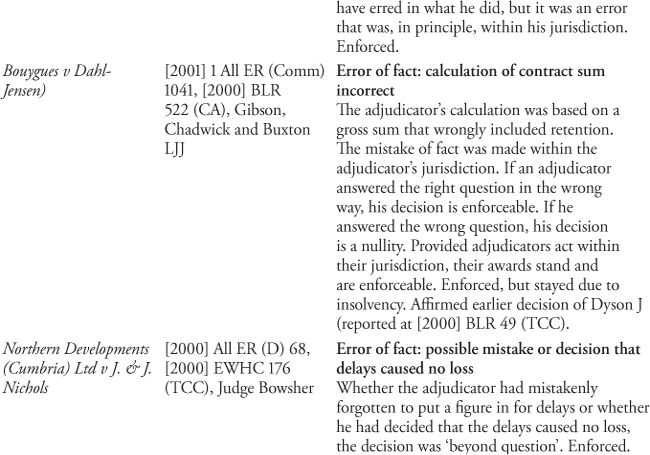

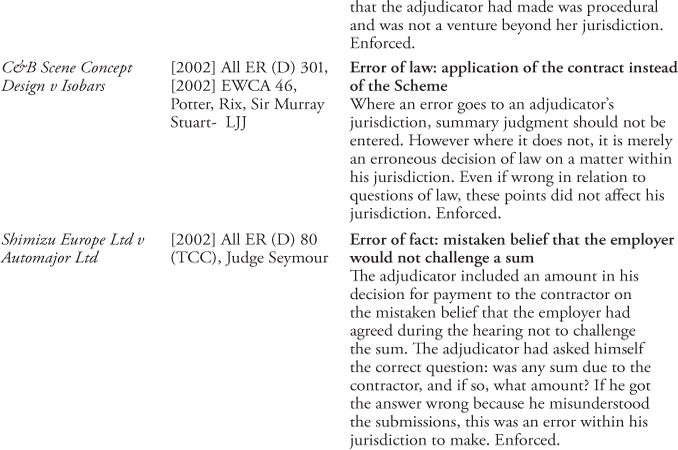

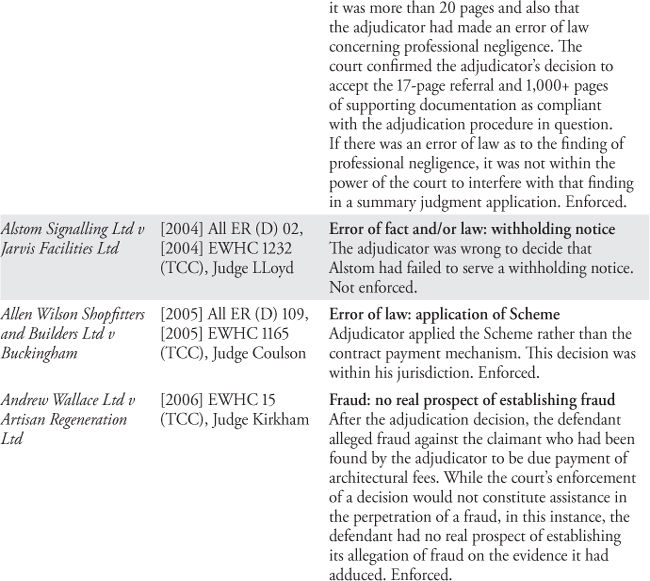

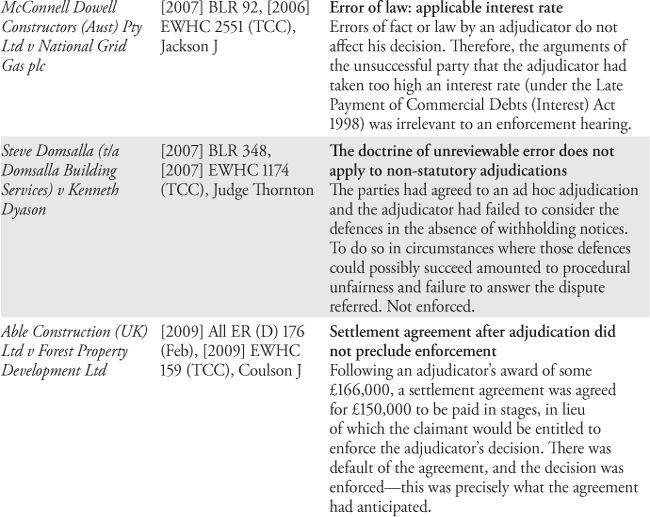

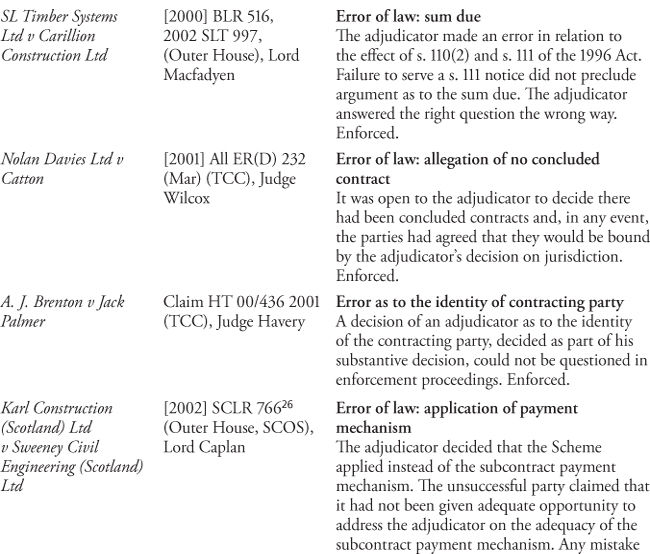

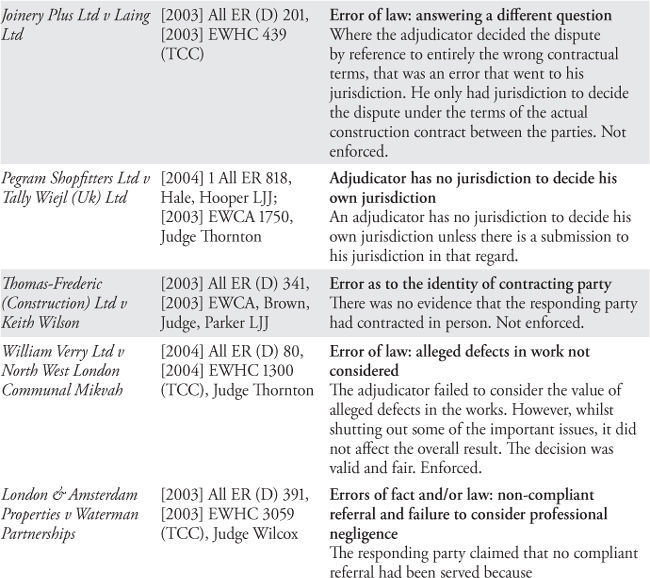

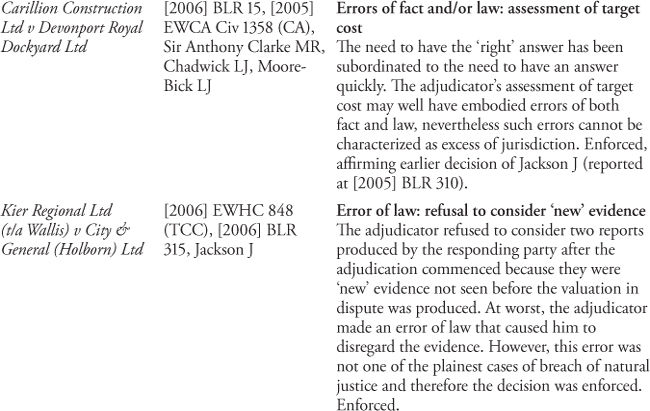

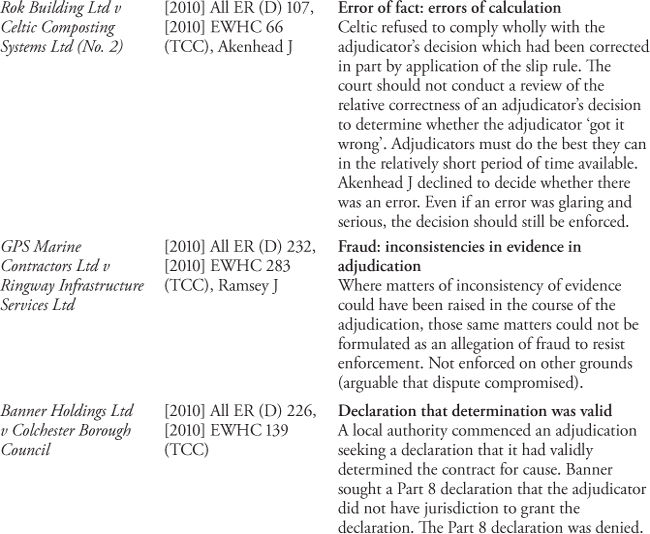

Errors of Fact and/or Law: Answering the Right Question the Wrong Way

7.05 It is now a well-established principle that an adjudicator’s decision should be enforced in all but the most exceptional circumstances.6 In particular, it will be no basis for resisting enforcement of a statutory decision7 to contend that the adjudicator reached conclusions that were wrong as a question of fact or a matter of law. The adjudicator has jurisdiction to decide the dispute referred. As long as the adjudicator answers the question referred for resolution (‘the right question’) that is referred to him the decision will be enforced even if the decision is wrong as a matter of fact or law. In Bouygues v Dahl-Jenson (2000),8 the adjudicator had wrongly taken account of a 5 per cent retention figure, which was not yet due for payment. The result of the error was a decision that a repayment of £140,000 was due instead of a payment of £200,000. The Court of Appeal stated that ‘unfairness in a specific case cannot be determinative of the true construction or effect of the scheme in general’.9 In other words the fact that the error resulted in unfairness was not a ground to challenge the validity of the decision.

7.06 The short time frame for adjudication means that ‘mistakes will inevitably occur’ but unless the mistake can be characterized as an excess of jurisdiction that would make the decision unenforceable it should be enforced.10 This is particularly so because the decision can ultimately be corrected during final determination of the dispute by court proceedings or arbitration.11 These principles have been confirmed in numerous Court of Appeal decisions since 2001.12

7.07 The exception to this principle (discussed in detail in Chapter 9) is if an error goes to the adjudicator’s jurisdiction—that is, where the adjudicator is either not empowered to consider the dispute at all or the adjudicator answers a question that is different from that referred. However, the courts will be slow to conclude that an error of fact or law is one that goes to jurisdiction and will examine any such error critically and with a degree of scepticism before they will accept that there has been an error of jurisdiction (or indeed a breach of the rules of natural justice).13 It is not for the court to examine the correctness of a decision which does not go to jurisdiction, even if it is glaring or serious, but rather to enforce the decision whether it was right or wrong.14

Challenges Based on Excess Jurisdiction or Breach of Natural Justice

7.08 There are two main bases for challenging the enforceability of an adjudicator’s decision: excess of jurisdiction or a breach of natural justice (including bias). Whilst adjudicators’ decisions should generally be enforced, if the adjudicator was not properly vested with jurisdiction or exceeded it, the decision will not be enforced. Similarly, if the adjudicator materially breached the rules of natural justice, or there was a reasonable apprehension of bias, actual bias or pre-determination. the decision will not be enforceable. These issues are addressed in Chapters 9 to 11, which identify the attempts—both successful and unsuccessful—that parties have made to avoid being bound by adjudicators’ decisions.

Fraud

7.09 It may also be possible to resist enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision on the grounds of fraud, but only in limited circumstances. The principles were addressed by the Court of Appeal in Speymill Contracts Ltd v Baskind (2010),15 which confirmed the approach taken in two previous TCC decisions.16 In Speymill it was held that if an allegation of fraud was or could have been raised before the adjudicator then it would be considered to have been adjudicated upon with the result that it could not be raised to resist enforcement. However, where the matters giving rise to the allegation of fraud had only emerged after the adjudication, then it may be possible to rely on them to resist enforcement, but only if the fraud directly impacts on the matters decided by the adjudicator (for example a certificate upon which the decision was based is later found to have been obtained by fraud).

Reservation of Position

7.10 In order to maintain a challenge to the enforceability of an adjudicator’s decision, a party should ensure that it adequately reserves its position at all stages during the course of the adjudication, or it may otherwise be deemed to have waived its right to object. Reservation of position is more fully discussed at 5.09–5.16.

Enforcement of Non-pecuniary Decisions

7.11 Where a party disagrees with an adjudicator’s decision and does not comply with it (usually by making the required payment within the timescale provided by the adjudicator) the successful party may apply to the courts to enforce the adjudicator’s decision, usually by way of summary judgment for payment of the sum in question. However, some decisions do not concern payment of an amount but award some other type of relief, for example a declaration or (where the adjudicator is so empowered) an order for specific performance. An adjudicator may give a declaratory decision about any issue under a contract, for example a declaration as to an entitlement to extension of time,17 or a declaration that determination for cause was valid.18 Section 108(3) and, if applicable, paragraph 23(2) of the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’) require parties to comply with the decisions of adjudicators and the courts have confirmed that compliance is necessary even where those decisions are declaratory.19

7.12 In Macob Civil Engineering Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd [1999] (Key Case)20 Dyson J said that the appropriate method of enforcement of declarations may be by way of declaration or mandatory injunction. The judge was specifically contemplating adjudicators’ decisions concerning the parties’ performance or non-performance of the contract such as returning to site, providing access or inspection facilities, opening up work, or carrying out specific work.21 In Multiplex Constructions (UK) Ltd v Mott MacDonald Ltd (2007) (Key Case),22 the claimant sought a declaration, an order for specific performance, and an injunction for the enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision that the defendant provide ‘all pertinent records’. The court found that it would be appropriate to enforce that decision by granting a declaration that the adjudicator’s decision was enforceable and the parties should comply with it. However the court rejected the applications for an order for specific performance and an injunction stating that neither was an appropriate route to enforcement in this case.

Enforcement where there is an Arbitration Agreement

7.13 An adjudicator’s decision can be enforced by the courts even where there is an arbitration agreement in the construction contract23 as discussed more fully at 8.43–8.48. However, any final determination of the dispute between the parties cannot be by the court.

Staying Enforcement

7.14 Whilst the general rule is that adjudicators’ decisions should be enforced without a stay of execution,24 there are limited grounds for requesting that the court exercises its discretion to stay the execution of enforcement of a decision, most frequently based on the impecuniosity of the successful party. Stay of execution of enforcement orders and stay of enforcement proceedings are discussed in Chapter 8.

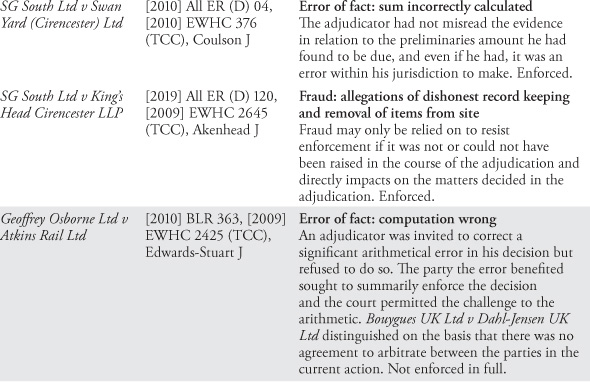

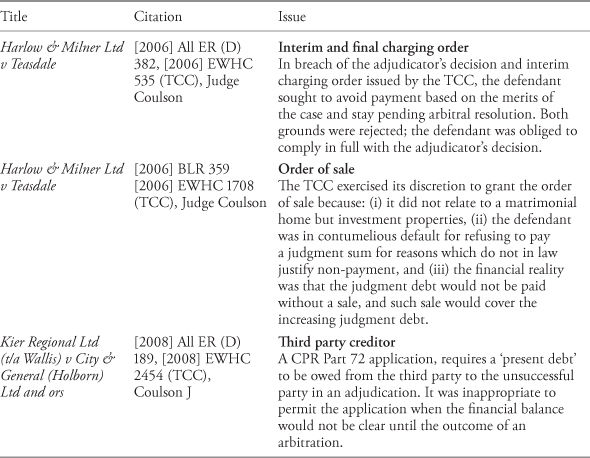

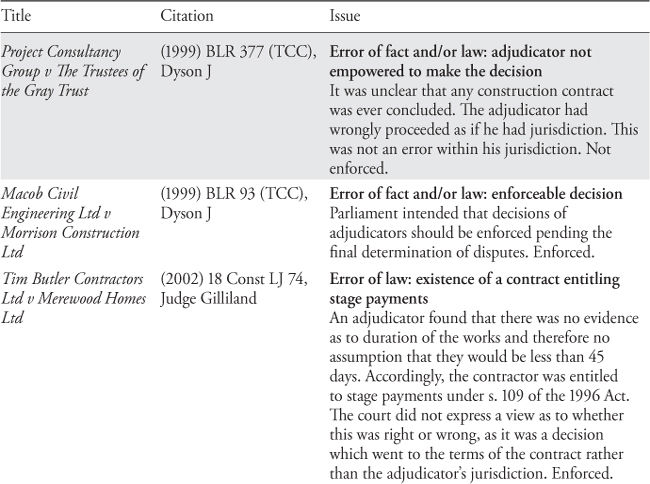

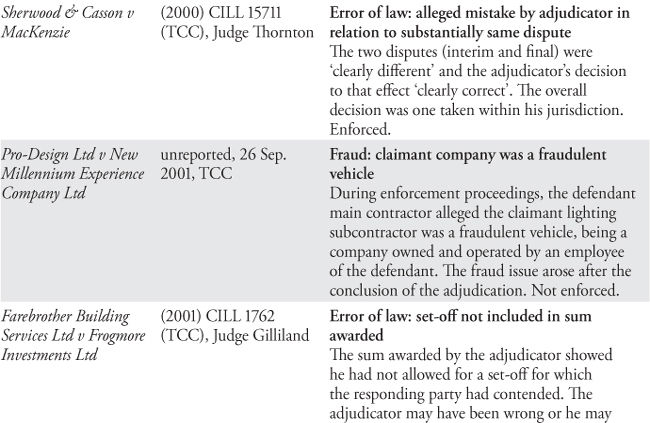

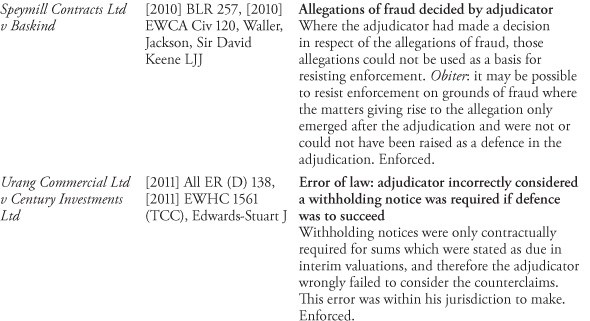

Key Cases: General Principles of Enforcement

Table 7.1 Table of Cases: General Principles of Enforcement (shaded entries indicate the decision was not enforced)

(3) Methods of Enforcement

7.20 Methods of enforcement include:

1. Summary judgment pursuant to part 24 of the CPR.

2. Enforcement by identical means to s. 42 of the Arbitration Act 1996 (as provided in paragraph 24 of the Scheme) where the adjudication was conducted under the Scheme and the adjudicator made a peremptory order (however this avenue was not encouraged Dyson J in Macob v Morrison).

3. Enforcement by mandatory injunction/specific performance (although recent case law indicates this is not permitted in Part 24 proceedings).

4. Winding up or bankruptcy proceedings where the sums are acknowledged as due and payable.

Summary Judgment

7.21 While it is now widely accepted that summary judgment is the appropriate course for enforcement of adjudicators’ decisions, this was not immediately apparent when the 1996 Act was introduced. In Macob Civil Engineering Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd (1999) (Key Case),27 Dyson J held that the fact that an adjudicator’s decision may later be revised was not a good reason for making summary judgment an inappropriate remedy. The grant of summary judgment did not pre-empt any later decision of an arbitrator or court—it simply reflected the fact that at the time the summary judgment was made, there was no defence to the payment of sums awarded by the adjudicator.

7.22 The last 14 years have confirmed Dyson J’s approach and successful parties now most commonly use the Special Procedure developed by the TCC for expedited summary judgment of enforcement claims under CPR 24 (discussed more fully at 7.41–7.67). Whilst there remain alternative methods of seeking enforcement of decisions of adjudicators,28 in most cases the judges of the TCC have given clear guidance that the appropriate course of action is to follow the TCC Special Procedure:

18. The … TCC Guide … makes it clear that the TCC will deal with all applications to enforce the decisions of adjudicators, regardless of the value of the decision, and will do so quickly and efficiently in accordance with a procedure worked out in consultation with the construction industry and the users of the court. … It is important that all parties to adjudication realise that, save in exceptional circumstances, the most efficient way of enforcing the adjudicator’s decision is by enforcement proceedings in the TCC. Other ways of enforcing such decisions (such as, for instance, bankruptcy proceedings) are something of a blunt instrument and raise potential issues which have little or nothing to do with the decision which is at the heart of any enforcement application.29

7.23 The TCC has recently reinforced that general financial limits for issuing claims in the TCC do not apply to adjudication claims.30

Alternative Methods of Enforcement

7.24 Notwithstanding the TCC’s clear preference for adjudication decisions to be enforced using its own bespoke procedure for enforcement, there are alternative methods that have been attempted by parties, with varying degrees of success.

Enforcement by Peremptory Order

7.25 The original Scheme contained a potential route to enforcement: paragraph 23(1) of the Scheme provides that the adjudicator may order compliance with his decision peremptorily, that is forthwith and without further investigation. Paragraph 24 says that s. 42 of the Arbitration Act 1996 (Arbitration Act) applies meaning the court may make an order that the parties comply with the adjudicator’s peremptory decision.

7.26 Notwithstanding the inclusion of this peremptory enforcement under the Scheme, there has been judicial reluctance towards this approach. For example, in Macob Civil Engineering Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd (1999) (Key Case),31 Dyson J confirmed that a court was empowered to enforce the decision pursuant to s. 42 of the Arbitration Act, but considered it was ‘not at all clear’ why s. 42 had been incorporated into the Scheme. The more appropriate remedy before the courts was summary judgment on the grounds that, at the time of judgment, there was no defence to enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision. Shortly after this decision, the TCC was asked to enforce an adjudicator’s decision, given as a peremptory order, in Outwing Construction Ltd v H. Randell & Son Ltd (1999).32 The court noted that there was no recognized procedure for enforcement of peremptory decisions but agreed that the claimant was entitled to seek enforcement by issuing a claim.33

7.27 Paragraph 24 of the Scheme has been removed following the introduction of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009. Therefore, adjudicators appointed to consider disputes arising under construction contracts entered into after 1 October 2011 will no longer have to consider whether to make their decisions take effect as peremptory orders.

Injunction/Specific Performance

7.28 In Macob Civil Engineering Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd (1999) (Key Case)34 Dyson J considered it was inappropriate to enforce adjudicators’ decisions for payment of sums due by means of a claim for a mandatory injunction.35 It would rarely be appropriate to grant injunctive relief to enforce an obligation on one contracting party to pay the other. Nevertheless the case leaves open the question of whether it might be appropriate to seek an injunction on different facts. Dyson J said the court had jurisdiction to grant a mandatory injunction to enforce an adjudicator’s decision which might be appropriate, for example, where a party was ordered by an adjudicator to make payment to a third party,36 or where the adjudicator’s decision contained declarations.37

7.29 However, in the case of Multiplex Constructions (UK) Ltd v Mott MacDonald Ltd (2007) (Key Case)38 Jackson J said that there was no basis on which the court in Part 24 proceedings could make an order for specific performance or grant an injunction.

Winding Up/Bankruptcy

7.30 A further alternative to issuing a claim for summary judgment to enforce an adjudicator’s decision is the use of winding up or bankruptcy proceedings. These will only be appropriate in limited circumstances, and may carry more inherent risks than the TCC Special Procedure. It has been successfully used in situations where sums were acknowledged as due and payable in accordance with an adjudicator’s decision, and no withholding notices had been issued.39

7.31 However, the insolvency proceedings approach was unsuccessful in George Parke v Fenton Gretton Partnership (2001)40 in which a judge in the Chancery Division considered Mr Parke had a bona fide counterclaim and set aside the statutory demand—one of the key reasons being that Mr Parke had commenced proceedings in the TCC on the basis that the final account showed a balance in his favour:

In my judgment it cannot be right that an employer or main contractor can be made bankrupt when it is known that he has proper proceedings on foot which, if successful, will result in a payment to him. I do not accept that the scheme of the 1996 Act is that an adjudication can be pursued to bankruptcy no matter the underlying state of account. The court would be required to close its eyes to the overall position, which in the context of bankruptcy is in my judgment wrong in principle.

7.32 Ultimately, whether an adjudicator’s decision can be pursued to insolvency will come down to consideration of the particular circumstances in each case and there is no overriding principle that such an approach is or is not valid in all cases. A key consideration in the exercise of discretion in restraining insolvency proceedings is the impression formed by the court of the strength of any counterclaim relied on.41