Easements

Easements

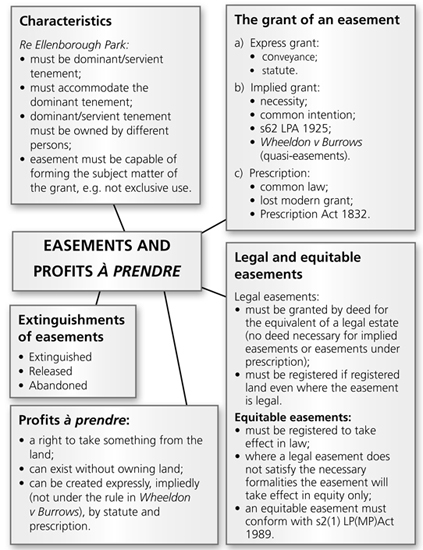

10.1 The Characteristics of Easements

1. An easement allows a landowner the right to use the land of another. It can be positive, e.g. a right to use a path over their land, or negative (not requiring any action by the claimant), e.g. a right to light.

2. It is a right that attaches to a piece of land and is not personal to the user.

3. The defining characteristics of an easement are laid down in Re Ellenborough Park (1956):

there must be a dominant tenement (land to take the benefit) and a servient tenement (land to carry the burden);

there must be a dominant tenement (land to take the benefit) and a servient tenement (land to carry the burden);

the easement must accommodate the dominant tenement (this means that it must benefit the land and not personally benefit the landowner) (Hill v Tupper (1863), Moody v Steggles (1879));

the easement must accommodate the dominant tenement (this means that it must benefit the land and not personally benefit the landowner) (Hill v Tupper (1863), Moody v Steggles (1879));

The essence of an easement is that it exists for the reasonable and comfortable enjoyment of the dominant tenement (Moncrieff v Jamieson and others (2007), Lord Hope);

The essence of an easement is that it exists for the reasonable and comfortable enjoyment of the dominant tenement (Moncrieff v Jamieson and others (2007), Lord Hope);

the two plots of land should be close to each other (Bailey v Stephens (1862));

the two plots of land should be close to each other (Bailey v Stephens (1862));

the dominant and servient tenements must be owned by different persons (you cannot have an easement over your own land but a tenant can have an easement over his landlord’s land);

the dominant and servient tenements must be owned by different persons (you cannot have an easement over your own land but a tenant can have an easement over his landlord’s land);

the easement must be capable of forming the subject matter of the grant:

the easement must be capable of forming the subject matter of the grant:

i) there must be a capable grantor and grantee, i.e. people who can grant and receive the benefit of an easement;

ii) it must be sufficiently definite, e.g. you cannot have an easement of a good view (Aldred’s Case (1610)) or an easement of good television reception (Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997));

iii) the right must be within the general nature of the rights traditionally recognised as easements (Dyce v Lady James Hay (1852));

iv) the right must not deprive the servient owner of all enjoyment of their property. A right of vehicular access may carry with it a right to park if it was necessary for the enjoyment of the easement (Moncrieff v Jamieson (2007)). An easement must not prevent any use by the landowner of his land but an easement may be upheld even if it severely limits the potential use of a landowner’s property (Virda v Chana and Another (2008)).

10.2 Other Features of Easements

1. The right must not impose any positive burden on the servient owner.

The duty to fence and to keep the fence in repair is an exception (Crow v Wood (1971)).

The duty to fence and to keep the fence in repair is an exception (Crow v Wood (1971)).

A landlord may have to maintain services for a tenant (Liverpool City Council v Irwin (1977)).

A landlord may have to maintain services for a tenant (Liverpool City Council v Irwin (1977)).

2. An easement must not amount to exclusive use (Copeland v Greehalf (1952)). Storage in a cellar was held to be exclusive use in Grigsby v Melville (1972) because it was a right to unlimited storage within a confined or defined space. Compare Wright v Macadam (1949), where an easement was upheld for a tenant who kept her coal in a shed preventing the landowner from any enjoyment of the shed for himself.

3. The right to park can be an easement so long as it is not exclusive use of the property and did not deprive the owner of use of his/her property (Batchelor v Marlow (2001)). In London & Blenheim Estates Ltd v Ladbroke Retail Parks Ltd (1992), it was held that parking in a general area or for a limited period of time could constitute an easement. Parking in a designated space may also be upheld.

4. In Moncrieff v Jamieson (2007) it was held that an easement of a right to park could be constituted as ancillary to a servitude right of vehicular access if it was necessary for the enjoyment of the easement of access. It was sufficient that it might have been in contemplation at the time of grant having regard to what the dominant proprietor might reasonably be expected to do in the exercise of his right to convenient and comfortable use of the property. The claimant lived on one of the Shetland Islands in Scotland. He had a vehicular easement over his neighbour‘s land. He also successfully claimed a right to park cars on the servient land because without this right the easement would have been ‘effectively defeated’.

5. The courts have been unwilling to extend the list of rights capable of existing as easements, although it has been said that easements must adapt to current changes (Dyce v Lady James Hay (1852)).

An easement can arise in three different ways:

express grant;

express grant;

implied grant;

implied grant;

prescription.

prescription.

10.3.1 Express Grant

1. An express grant of an easement arises through the use of express words incorporated into a transfer of a legal estate, e.g a purchaser is granted rights of drainage and rights of way.

2. As the grant is incorporated into a deed of transfer or lease it will take effect at law.

3. Easements can also be granted by estoppel, where the grantee has relied on a promise of rights and acted to his/her detriment (Crabb v Arun District Council (1976)).

4. Easements can be expressly granted by statute, e.g. the grant is made in favour of privatised utilities such as the supply of gas or water, or the power to lay sewers.

10.3.2 Implied Grant

1. The grant of an easement can be implied into the deed of transfer although not expressly incorporated.

2. An implied easement will take effect at law because it is implied into the transfer of the legal estate.

3. In registered land the easement may take effect as an overriding interest, although the LRA 2002 has reduced the circumstances for this.

4. Any easement that is the subject of an implied grant must conform with the characteristics of an easement laid down in Re Ellenborough Park (1956).

5. Categories of implied grant:

a) Easements of necessity:

generally imply a right of access;

generally imply a right of access;

are allowed because without the easement the land would be incapable of use;

are allowed because without the easement the land would be incapable of use;

are not available where an alternative route would simply be inconvenient (Nickerson v Barraclough (1981)) only if the alternative access is totally unsuitable for use.

are not available where an alternative route would simply be inconvenient (Nickerson v Barraclough (1981)) only if the alternative access is totally unsuitable for use.

Under statute, Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992 gives a neighbour the right to seek a court order to gain access to his neighbour’s land to carry out essential repairs. This is not automatic and must be applied for through the court. It is a registrable right.

Under statute, Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992 gives a neighbour the right to seek a court order to gain access to his neighbour’s land to carry out essential repairs. This is not automatic and must be applied for through the court. It is a registrable right.

b) Easements of common intention:

Rights are presumed to be within the intention of the parties and, unless these rights are expressly excluded, they will be enforceable (Wong v Beaumont Property Trust Ltd (1965)). In Wong the claimant leased basement premises to be used as a Chinese restaurant. The landlord knew it needed ventilation to comply with public health regulations but he would not allow the tenants to fix a duct on his land which would then enable a ventilation system to be fitted. Without the ventilation shaft the premises would have been unsuitable for use.

Rights are presumed to be within the intention of the parties and, unless these rights are expressly excluded, they will be enforceable (Wong v Beaumont Property Trust Ltd (1965)). In Wong the claimant leased basement premises to be used as a Chinese restaurant. The landlord knew it needed ventilation to comply with public health regulations but he would not allow the tenants to fix a duct on his land which would then enable a ventilation system to be fitted. Without the ventilation shaft the premises would have been unsuitable for use.

There must be evidence of intention, but the use need not be necessary for the enjoyment of the property.

There must be evidence of intention, but the use need not be necessary for the enjoyment of the property.

Some overlap with easements of necessity.

Some overlap with easements of necessity.