DIRECTORS’ DUTIES: GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS AND MANAGEMENT DUTIES

Directors’ duties: General considerations and management duties

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Discuss the rationale behind reform of directors’ duties

Discuss the rationale behind reform of directors’ duties

Discuss the extent to which the statutory statement of directors’ duties is a codification

Discuss the extent to which the statutory statement of directors’ duties is a codification

Understand to whom directors’ duties are owed

Understand to whom directors’ duties are owed

Understand the concept of enlightened shareholder value and how it has been introduced into directors’ duties

Understand the concept of enlightened shareholder value and how it has been introduced into directors’ duties

Appreciate when directors must focus on the interests of creditors

Appreciate when directors must focus on the interests of creditors

Distinguish management duties and conflict of interest duties

Distinguish management duties and conflict of interest duties

Identify general management duties and specific management duties

Identify general management duties and specific management duties

Understand how the four general management duties operate:

Understand how the four general management duties operate:

to act within powers (s 171)

to act within powers (s 171)

to promote the success of the company (s 172)

to promote the success of the company (s 172)

to exercise independent judgment (s 173)

to exercise independent judgment (s 173)

to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence (s 174)

to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence (s 174)

11.1.1 Approach to the study of directors’ duties

The legal duties of directors are such an essential part of the legal corporate governance framework that three chapters are needed to do them justice. Following introductory remarks, the following structure is adopted for the study of directors’ duties and the key statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors:

legislative reform (Chapter 11);

legislative reform (Chapter 11);

to whom the duties are owed (Chapter 11);

to whom the duties are owed (Chapter 11);

management duties (Chapter 11);

management duties (Chapter 11);

conflict of interest duties (Chapter 12);

conflict of interest duties (Chapter 12);

statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors (Chapter 12);

statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors (Chapter 12);

remedies and relief for breaches and contraventions (Chapter 13).

remedies and relief for breaches and contraventions (Chapter 13).

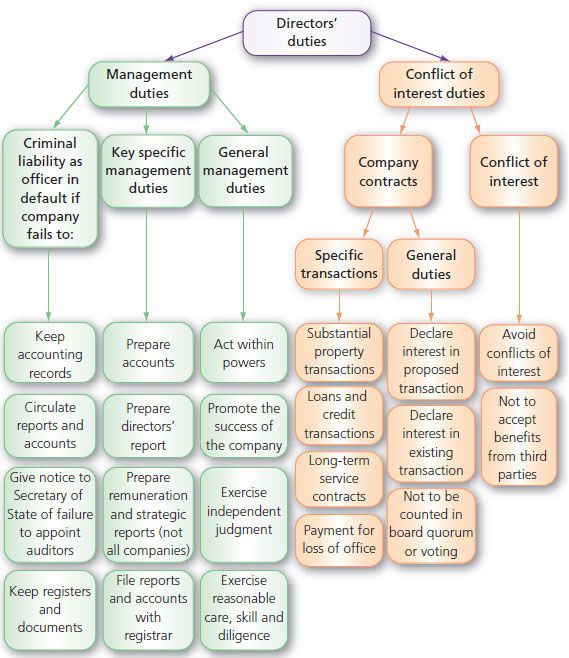

In this book, directors’ duties are classified into management duties and conflict of interest duties. This classification, depicted diagrammatically in Figure 11.1, is not a classification found in law but is adopted to assist your understanding of when individual duties are typically and primarily engaged. You should take a few minutes to familiarise yourself with the classification in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1 Categorisation of directors’ duties.

11.1.2 Control of director conflicts of interest

Traditionally, the primary role of directors’ duties has been to discourage individuals responsible for the management of companies (see Model Article 3) from acting in their own self-interest or in the interest of persons other than the company. It is because the directors of a company are empowered to alter the legal position of the company and in doing so are entrusted to act in the best interests of the company that they are subject to fiduciary obligations. You will come across fiduciary responsibility in agency and trust law but note that as a fundamental legal concept underpinning English law, it is not confined to trustees and agents.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| York Building Co v MacKenzie (1795) 3 Pat 378 ‘He that is entrusted with the interest of others cannot be allowed to make the business an object of interest to himself; because from the frailty of nature, one who has the power will be too readily seized with the inclination to use the opportunity for serving his own interest at the expense of those for whom he is entrusted.’ | |

Protecting rights, particularly property rights, and establishing standards for human conscience when individuals are entrusted to protect the rights of third parties are regarded as proper matters for the civil law courts. Conflict of interest has long been discouraged by the English courts and stringent remedies awarded against transgressors.

11.1.3 Control of directors’ management behaviour

In contrast with controlling conflicts of interest, traditionally, judges have exhibited less interest in managerial competence. Courts have not considered it to be their role to create incentives for good management. To do so would inevitably draw judges into making judgments about the reasonableness of business decisions, a role they acknowledge they have no particular competence to play. It is only relatively recently that the law has given any meaningful content to what are termed here ‘management duties’ of directors, a development shaped by legislative intervention. Essentially, the approach of the law is to require directors to arrive at decisions by satisfactory processes rather than to review the substance of those decisions.

Two contentious issues underlie the construction of the duties imposed on directors to bring about good management of companies (or, put another way, to enhance corporate governance). One issue is whether directors’ behaviour should be assessed subjectively or objectively. In some respects the law has evolved towards objective assessment, a good illustration of which is the s 174 duty to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence. However, subjective assessment remains central to key duties, such as the s 172 duty of a director to act in the way he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company. Each of these duties is considered in greater detail later in this chapter.

The far more contentious underlying issue concerns the ultimate objective of companies: what is it that directors should be seeking to achieve as they manage or govern a company? Theories about what companies are for, or what they should be for, were considered at the end of Chapter 9. UK company law has traditionally reflected the theory that a company should be run for the benefit of its shareholders, present and future, as a whole (see Hutton v West Cork Railway Co (1883) 23 Ch D 654, Gaiman v National Association for Mental Health [1971] Ch 317, Brady v Brady [1989] AC 755 (HL)) and this remains the legal position today (s 172(1)). Precisely what is meant by ‘the benefit of its shareholders’ is unclear which makes it of limited help in determining how directors should behave. When the Companies Act 2006 was written, concern to shift the basis for corporate decision-making away from what is perceived to be excessive concern with short-term financial returns to shareholders resulted in the ‘shareholder value’ theory being recast as the ‘enlightened shareholder value’ theory. The importance of this change in the law (which manifests itself in s 172(1)) was somewhat exaggerated by the Rt Hon Margaret Hodge MP, Secretary of State for Trade and Industry (as she then was), in her Ministerial Statement on the reforms being introduced:

QUOTATION

‘There are two ways of looking at the statutory statement of directors’ duties: on the one hand it simply codifies the existing common law obligations of company directors; on the other – especially in section 172: the duty to act in the interests of the company – it marks a radical departure in articulating the connection between what is good for a company and what is good for society at large.’

enlightened shareholder value

The doctrine enshrined in the Companies Act 2006, s 172, whereby although directors must act in the way they consider, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, in performing this duty they must have regard to the interests of other stakeholders and the long-term consequences of any decision

Enlightened shareholder value is far from radical. It preserves enhancement of the interests of shareholders as the objective of companies and it exists within a legal corporate governance framework in which shareholders are the monitors of the directors’ pursuit of that objective (see section 11.3.2 where the question of to whom directors owe their duties is discussed).

Before turning to examine the statutory directors’ duties individually, it is helpful to consider a number of general issues relating to directors’ duties.

11.2 Legislative reform of directors’ duties

Directors’ general duties were developed over time by the courts and remained case based until the Companies Act 2006.

11.2.1 Statutory regulation of particular transactions

In contrast to the general duties, statutory provisions regulating specific transactions between a director and the company were first introduced in 1928. Prompted by financial scandals, the statutory provisions were significantly enhanced in 1980 which marked the high tide of statutory regulation of director self-interest. For example, company loans above a minimal amount to directors were prohibited and criminalised. The 2006 Act removed this prohibition in favour of shareholder approval.

11.2.2 General duty codification initiatives

The general duties have not been ignored by governments through the twentieth century. A long line of committees considered consolidating or codifying general directors’ duties. In 1895, the Davey Committee recommended that the duties and liabilities of promoters and directors in respect of the promotion of companies and the issue of prospectuses should be set out in statute because:

QUOTATION

‘The incorporation of those principles in an Act of Parliament is more likely to bring home to promoters and directors the obligations they undertake and to shareholder and others the standard of commercial morality which they have a right to expect in those whom they are invited to trust.’

Adopting a less defeatist stance, the Jenkins Committee, reporting in 1962, recommended a statement of the basic principles underlying the fiduciary duties owed by a director to the company. Far from codification, the statement was intended to be non-exhaustive. The Companies Bill 1973 contained statutory provisions stated to be ‘in addition to and not in derogation of any other enactments or rules of law relating to the duties or liabilities of directors of a company’. Unfortunately, the bill fell with the government in the first 1974 general election. A much more ambitious Companies Bill appeared in 1978. It contained duties stated to have effect ‘instead of any rule of law stating the fiduciary duties of directors of companies’. Subject to severe criticism, events overtook it and in 1979 it too fell with the government.

A Department of Trade and Industry (DTI, now the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, or BIS) working party on directors’ duties from 1993–95 failed to publish proposals, and directors’ duties were next considered by the Law Commission in the late 1990s, resulting in a lengthy consultation paper entitled ‘Company Directors: Regulating Conflicts of Interest and Formulating a Statement of Duties’ (No 153, 1998). Published after the DTI (now BIS) announcement of the 1998 Company Law Review, the consultation paper significantly influenced adoption of a statutory statement of directors’ duties in the Companies Act 2006.

11.2.3 Rationale for the 2006 reform

After the passing of the 2006 Act, Margaret Hodge articulated two aims of the reform of directors’ duties. A third aim is found in the Law Commission’s consultation paper on directors’ duties:

providing clarity and accessibility;

providing clarity and accessibility;

aligning what is good for the company with what is good for society at large;

aligning what is good for the company with what is good for society at large;

keeping legal regulation to the minimum necessary to safeguard stakeholders’ legitimate interests.

keeping legal regulation to the minimum necessary to safeguard stakeholders’ legitimate interests.

Each is worthy of further consideration.

Providing clarity and accessibility

It remains too early to tell whether the post-2006 Act law on directors’ duties is clearer, easier to understand and more accessible than the old law. Certainly, the headline duties are drawn together in one place in the Act. As comments in the codification section below indicate, however, the statutory provisions far from comprehensively cover all issues relevant to a director’s liability for breach of duty. It is likely that in many situations directors will continue to need to seek legal advice to understand their legal duties and the procedures available to avoid incurring liability. If this turns out to be the case, the Act will not have achieved its principal stated aim in relation to directors’ duties. In the recent evaluation of the Act commissioned by BIS it is suggested that added clarity of s 172 is needed, having somewhat worryingly found evidence of directors entering into limited liability agreements with auditors ‘whilst openly acknowledging they do not know of any benefits to their company’.

Aligning what is good for the company with what is good for society at large

In the reform process, debate between pluralists advocating the running of companies in the interests of the plurality of stakeholders and those endorsing the shareholder value theory was circumscribed. Pluralist arguments faltered on the difficulty inherent in the task of establishing a mechanism of control of directors different from shareholder control. The result is that alignment of what is good for the company with what is good for society at large is to be achieved by language enshrined in s 172. This language requires directors to ‘have regard to’ the interests of the plurality of stakeholders when taking business decisions. This is the long and the short of the much trumpeted ‘enlightened shareholder value’. The obligation forms part of the duty of directors to act in the way they consider will be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of the shareholders as a whole. That duty is performed in a boardroom of individuals who are appointed and removable by shareholders and who owe their duties to the company, the enforcement of which duty can be instigated by the directors themselves or by shareholders (s 172(1)).

Again, it is premature to comment on the extent to which the new directors’ duties will bring about a change for the good of society in the way directors make decisions. The extent to which greater emphasis will be placed on the interests of non-shareholder stakeholders, including ‘the community and the environment’ (s 172(1)(d)), and ‘the likely consequences of any decisions in the long term’ (s 172(1)(a)), remains to be observed.

Keeping legal regulation to the minimum necessary to safeguard stakeholders’ legitimate interests

Economic theory has provided the principal perspective and methodology for assessing the effect of company law on commercial behaviour and predicting the effects of proposed changes to company law. The Law Commission embraced this perspective in the late 1990s. It analysed directors’ duties from the starting point of the need to justify laws that interfere in and restrict business behaviour. It identified the need to strike a balance between ‘necessary regulation and freedom for directors to make business decisions’ as a key principle to be applied by policy-makers in considering how to reform company law and it identified ‘graduated regulation of conflicts of interest’ and ‘efficient disclosure’ as two further headline principles to guide reform of the law of directors’ duties.

11.2.4 Have the general duties been codified?

Deliberate changes to case-based general duties

Although the general duties of directors set out in the 2006 Act are in large part a statutory statement of the duties as developed by the courts, those duties have been deliberately amended in a number of ways. It is not just a case of the common law and equitable duties having been stated in the statute.

Relationship between the Act and the articles

The Act has changed the respective roles of the statutory provisions and the articles of a company in the regulation of directors’ conflicts of interest, particularly in relation to the declaration of interest of a director in a company contract (see Chapter 12). Note that a company’s articles remain an important component in determining the procedures required to protect directors from liability for breach of duty. Section 180(4) expressly provides that the general duties are not infringed by anything done (or omitted) by the directors in accordance with provision for dealing with conflicts of interest in the company’s articles.

Do the statutory duties replace the case-based duties?

Section 170(3) appears to state that the general duties in the Act replace case-based directors’ duties.

SECTION

‘The general duties are based on certain common law rules and equitable principles as they apply in relation to directors and have effect in place of those rules and principles as regards the duties owed to a company by a director.’

The precise legal position is much more complicated than this and, rather than clarifying and making the law more accessible, it may turn out that the statutory statement has added a further layer to the legal analysis of a given situation to determine whether or not a director is in breach of duty and, if so, the remedies available.

First, a close reading of s 170(3) shows that the statutory duties have replaced ‘certain common law rules and equitable principles’. It does not state that ‘all’ common law rules and equitable principles have been replaced. This indicates an understandable reluctance on the part of the reformers to inadvertently overlook a case-based duty. Unfortunately, it leaves the door open for obscure common law rules and equitable principles to be resurrected based on the argument that they are not the rules or principles on which the statutory duties were based.

Second, the meaning of the general duties is still to be found in case law (s 170(4)).

SECTION

‘The general duties shall be interpreted and applied in the same way as common law rules or equitable principles, and regard shall be had to the corresponding common law rules and equitable principles in interpreting and applying the general duties.’

Third, the remedies for breach of duty have not been stated in the statute, rather, s 178(1) provides that the remedies are the same as for the corresponding common law rule or equitable principle.

SECTION

‘The consequences of breach (or threatened breach) of sections 171–177 are the same as would apply if the corresponding common law rule or equitable principle applied.’

Authorisation and ratification

Even if we assume that the general duties are a clear statement of the main duties of directors, the 2006 Act has not sought to comprehensively state the law relating to the giving of authority or ratification by the company of behaviour that would otherwise be a breach of duty. The general duties are stated in s 180(4) to have effect ‘subject to any rule of law enabling the company to give authority, specifically or generally, for anything to be done (or omitted) by the directors, or any of them, that would otherwise be a breach of duty’.

Consequently, the Act does not make it clear, nor is the law accessible to determine, whether or not a director may be sued for breach of duty in circumstances in which the director seeks to establish that he has been authorised to behave as he did, or subsequently excused.

11.3 To whom do directors owe their duties?

11.3.1 Directors’ duties are owed to the company

The statutory general duties of directors are owed by each individual director to the company (s 170(1)). Consequently, any action for breach of duty vests in the company (Foss v Harbottle [1843] 2 Hare 461, considered in Chapter 14). Without more, a director does not owe duties to individual shareholders or to other stakeholders in the company (Percival v Wright [1902] 2 Ch 421).

When considering the conflict of interest duties of directors it is sufficient to require the director to act in the interests of ‘the company’ as the company’s interests can be contrasted with the directors’ own self-interest or the interest of a person external to the company. When considering the management duties of directors, however, it becomes necessary to penetrate further and ask what is meant by the interests of the company.

11.3.2 Enlightened shareholder value

Company law requires directors to treat the interests of the shareholders as a whole as paramount when making decisions. This is captured in s 172 which requires directors to act in the way they consider to be most likely to promote the success of the company ‘for the benefit of its members as a whole’ (members meaning shareholders for our purposes). In performing this duty, however, the directors must have regard to the interests of other stakeholders, particularly those listed in s 172(1). As indicated above, it is this obligation that underpins the description of the ‘shareholder value’ theory underlying directors’ duties as ‘the enlightened shareholder value’ theory.

SECTION

‘172 Duty to promote the success of the company

(1) A director of a company must act in the way he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, and in doing so have regard (amongst other matters) to –

(a) | the likely consequences of any decision in the long term, |

(b) | the interests of the company’s employees, |

(c) | the need to foster the company’s business relationships with suppliers, customers and others, |

(d) | the impact of the company’s operations on the community and the environment, |

(e) | the desirability of the company maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct, and |

(f) | the need to act fairly as between members of the company.’ |

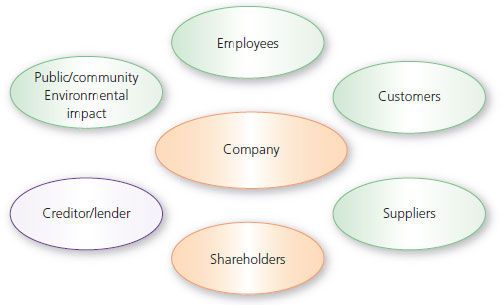

The various interests directors are required to take into account as part of acting for the benefit of the shareholders as a whole are illustrated in Figure 11.2.

11.3.3 The interests of creditors

The extent to which directors are required to take the interests of creditors into account when they are managing the company is a very important issue. Creditors are not listed alongside other obvious stakeholders in s 172(1). Instead, s 172(3) makes the duty to promote the success of the company ‘for the benefit of its members as a whole’ subject to ‘any enactment or rule of law requiring directors, in certain circumstances, to consider or act in the interests of creditors of the company’.

The interests of creditors predominate when there is no residual wealth left in the company, that is, when shareholder equity has been dissipated, usually by poor trading (see Chapters 7 and 8). At that point, the economic owners of the company are the creditors: all the company has it owes to them. As the financial health of a company deteriorates, the directors need to increasingly focus on the interests of the creditors when they take decisions because the interests of the company become increasingly aligned with the interests of its creditors (Facia Footwear Ltd v Hinchcliffe [1998] 1 BCLC 218).

At the relevant point when the duty becomes ‘creditor regarding’, be it on insolvency (West Mercia Safetywear v Dodd (1988) 4 BCC 30), or at some point before insolvency, such as when the company is ‘doubtfully solvent’ (Brady v Brady [1988] BCLC 20 (CA)) (the courts have not been able to agree on the point at which the need to prioritise the interests of creditors is triggered), it is not a question of the directors owing a duty to the creditors: the duty remains owed to the company. The duty simply needs to be performed with different priorities in mind. The duty remains enforceable against the directors only by the company but note that the shareholders cannot ratify what would otherwise be a breach of duty (Sycotex Pty Ltd v Balser (1993) 13 ACSR 766).

The common law and equitable principles requiring directors, in certain circumstances, to consider or act in the interests of creditors, preserved by s 172(3), have not had to be developed in case law in recent years due to the enactment of s 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986. Section 214 applies when a company is being wound up. It exposes directors to court orders to contribute to the assets of the company if knowing, or in circumstances in which they ought to have known, that the company had no reasonable prospect of not going into insolvent liquidation, they continued to trade or otherwise took steps not in the interests of creditors. Section 214 and other protections for creditors on a winding up are considered in Chapter 16.

Figure 11.2 Enlightened shareholder value and s 172.

QUOTATION

‘[T]he implementation of the allegedly ineffective wrongful trading liability that has not yet matched up to its expectations highlights the need to reassess common law duties concerning creditors in the United Kingdom. The commonly used term “duty to creditors” is a misnomer as fiduciary duties do not provide either directors with clear guidelines with regard to economical decisions, or creditors with directly enforceable claims. The UK duty to creditors provides only mitigated creditor protection by sanctioning the misappropriation of company funds and other serious opportunistic behaviour, although British company and insolvency law seems to be well equipped to deal with this type of conduct: for instance, the rules on undervalue transactions and preferential payments (s.238, 239 IA 86) efficiently redeem commercially inadequate transfers or endowments of company funds.

Though it is arguable whether directors should, when a company remains solvent yet financially instable, prioritise creditor interests when two courses of action are available, courts and legislators in both Germany and the United Kingdom have chosen not to pursue such an approach in order not to unduly restrict managerial discretion. Academic attention in both jurisdictions has thus shifted towards the duty of care and skill as a means of creditor protection … In particular the consultation of professional advisers and the initiation of directors’ and shareholders’ meetings to review the company’s situation at an early stage in the company’s decline may, de lege lata and ferenda, offer an effective back door to escape responsibility in both jurisdictions. This approach is both feasible and superior to redirecting fiduciary duties to creditors as directors are provided with hands-on recommendations and courts with straightforward criteria to evaluate liability.’

Lotz 2011 at p. 269 (footnotes omitted)