Criminal Liability of Security Personnel

5

Criminal Liability of Security Personnel

Chapter outline

Introduction: The Problem of Criminal Liability

Criminal Liability under the Federal Civil Rights Acts

Criminal Liability and the Regulatory Process

Defenses to Criminal Acts: Self-Help

Use of Force in Self-Protection

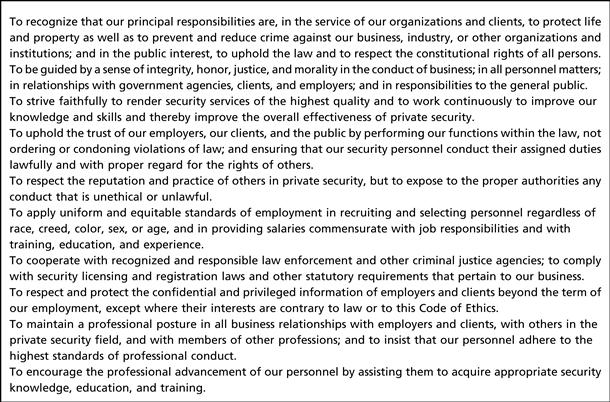

Private Security and Miranda Warnings

Introduction: The Problem of Criminal Liability

Although civil liability problems are natural risks in the security industry, the panorama of liability extends beyond the civil realm and into the criminal context. While the term “liability” is acceptable in criminal settings, the more accurate term might be “culpability.” In short, how can and does the security operative become responsible for and culpable under criminal constructions? Can the security industry, as well as its individual personnel, suffer criminal liability? Can security personnel, in both a personal and professional capacity, commit crimes? Are security corporations, businesses, and industrial concerns capable of criminal infraction, or can these entities be held criminally liable for the conduct of employees? Are there other criminal concerns, either substantive or procedural, that the security industry should be vigilant about?

As the privatization of once historic criminal justice functions continue, corresponding civil and criminal liability questions will remain and even accelerate. Security professionals engage the public in so many settings and circumstances that it is a sure bet that criminal conduct will be witnessed.

While the content of the chapter will glance at procedural issues raised in Chapter 3, its main thrust shall be on criminal codification and analysis of criminal definition.

Criminal Liability under the Federal Civil Rights Acts

Although security operatives may directly act in a criminal manner, or either aid or abet others, or even neglect duties and responsibilities resulting in liability based on omission, their particular actions, under diverse statutory and codified laws, may give rise to criminal culpability. In the area of the federal Civil Rights Act, the prosecutorial authority has the latitude to charge a criminal action. While the majority of litigation and actions under 42 U.S.C. §1983 have been, and continue to be, civil in design and scope, Congress has enacted legislation that attaches criminal liability for persons or other legal entities acting under color of state law, ordinance, or regulation who are

b. Willfully subjecting any inhabitant to a different punishment or penalty because such an inhabitant is an alien because of his race or color, then as prescribed for the punishment of citizen1

The body of case law and literature relative to section 1983 is now legion in size. Visit http://library.findlaw.com/1999/Jan/1/126485.html.

While criminal liability can be grounded within the statutory framework, advocates of this liability must still pass the statutory and judicial threshold question—that is, whether or not the processes and functions of private justice can be arguably performed under “color of state law.” As discussed previously, either the state action or the color of state law advocacy requires evidential proof of private action metamorphosing into a public duty or function or of governmental authorities depriving a citizen of certain constitutional rights. The U.S. Supreme Court argued in Evans v. Newton 2 that

[c]onduct that is formally “private” may become so entwined with governmental policies or so impregnated with governmental character as to become subject to the constitutional limitations placed upon state action … when private individuals or groups are endowed by the State with powers or functions governmental in nature, they become agencies and instrumentalities of the State and subject to its Constitutional limitations.3

Contemporary judicial reasoning has yet to reach the point where private security practices are synonymous with public activities, though litigators are not shy about alleging this claim. Courts are less willing to entertain the argument as a basis for a case in chief or as an argument for remedy. This judicial reticence has precipitated often scathing criticisms by practitioners and academics. The Hofstra Law Review, when assessing the constitutional ramifications of merchant detention statutes concludes:

By judicial decision and statute a “super police” has been created. The merchant detective has the same privileges as public law enforcement agents without the same restraints to neutralize the effect of a violation of constitutionally protected rights. The merchant detective is treated as a private citizen for purposes of defining his constitutional liabilities and yet he is granted tort immunity as though he were a public law enforcement agent.4

While this argument may have intellectual support, it generally disregards the practical realities of operating retail or other commercial establishments. Retail establishments and industrial units—whose chief justice function is asset protection—would find most public policing protections incompatible with their fundamental mission.

Criminal liability can also be imposed under the federal Civil Rights Act if, and when, a victim of illegal state action shows that the injurious action was the product of a conspiracy. The relevant provision as to conspiracy states:

a. A conspiracy by two or more persons;

b. For the purposes of injuring, oppressing, threatening or intimidating any citizen in the free exercise or enjoyment or past exercise of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States.5

Various factual scenarios illustrate this statutory application:

In sum, the pressing crossover question in the world of private security still remains whether or not private justice agents can be held to public scrutiny.

Criminal Liability and the Regulatory Process

Since the private security industry is subject to the regulatory oversight of governmental authorities, there is always a chance that criminal culpability will rest or reside in the failure to adhere to particular guidelines.

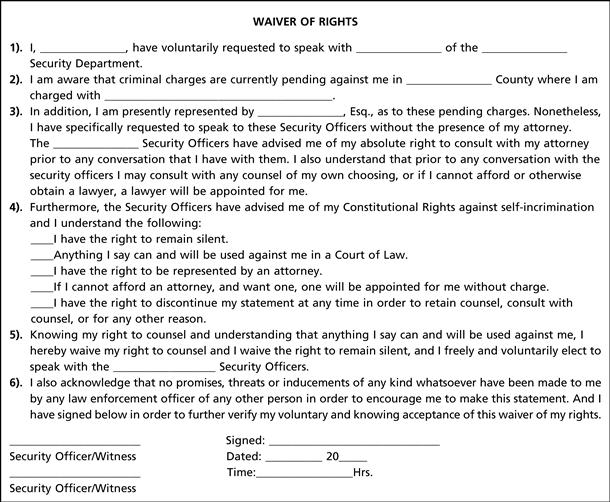

A repetitive theme originating with the RAND Study,6 through the National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, to the recent Hallcrest Report II, is the need for regulations, standards, education and training, and qualifications criteria for the security industry.7 The National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, citing the enormous power wielded by the private security industry, urges, through the adoption of a National Code of Ethics, professional guidelines. See Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Ethical code for managers.

The National Advisory Committee further relates:

Incidents of excessive force, false arrests and detainment, illegal search and seizure, impersonation of a public officer, trespass, invasion of privacy, and dishonest or unethical business practices not only undermine confidence and trust in the private security industry, but also infringe upon individual rights.8

In short, the commission recognizes that part of the security professional’s measure has to be the avoidance of every criterion of crime and criminality. The regulatory and administrative processes involving licensure infer a police power to punish infractions of the promulgated standards.

A recent Arizona case, Landi v. Arkules, 9 delivers some eloquent thoughts on why licensing and regulation are crucial policy considerations. In declaring a New York security firm’s contracts illegal because of a lack of compliance, the court related firmly:

The statute imposes specific duties on licensees with respect to the confidentiality and accuracy of information and the disclosure of investigative reports to the client.10 A license may be suspended or revoked for a wide range of misconduct, including acts of dishonesty or fraud, aiding the violation of court order, or soliciting business for an attorney.11

The Legislature’s concern for the protection of the public from unscrupulous and unqualified investigators is woven into the legislative or regulatory intent of these controls. This concern for the public’s protection precludes enforcement of an unlicensed investigator’s fee contract.12 The courts will not participate in a party’s circumvention of the legislative goal by enforcing a fee contract to provide regulated services without a license.13

Hence, security professionals may incur criminal liability for failure to adhere to regulatory guidelines. States have not been shy about this sort of regulation. A California statute prohibiting the licensure of any investigator or armed guard who has a criminal conviction in the last 10 years was upheld.14 A Connecticut statute for criminal conviction was deemed overly broad.15

As states and other governmental entities legislate standards of conduct and requirements criteria in the field of private security, the industry itself has not been averse to challenging the legitimacy of the regulations. Antagonists to the regulatory process urge a more privatized, free-market view and balk at efforts to impose criminal or civil liability for failure to meet or exceed statutory, administrative, or regulatory rules and guidelines.16 Some fascinating legal arguments have been forged by those challenging the right of government to regulate the security industry. The argument that state law preempts any local control of the security industry has failed on multiple grounds.17 Other advocates attack regulation by alleged defects in due process.18 Litigation has successfully challenged the regulatory process when ordinances, administrative rules, regulations, or other laws do not provide adequate notice, are discriminatory in design, or have other constitutional defects.19 A legal action revoking an investigator’s license was overturned despite a general investigator’s criminal conviction since he merely pled nolo contendere rather than “guilty.”20 A plea in this manner is no admission, the court concluded, and thus failed the evidentiary burden of actual criminal commission. Other challenges to the validity and enforceability of the regulatory process in private security include the argument that such statutory oversight violates equal protection of law,21 or that the regulatory process is an illegal and unfounded exercise of police power,22 or an unlawful delegation of power.23 As a general observation, these challenges are largely ineffective.24

Given the minimal intrusion inflicted on the security industry by governmental entities, and the industry’s own professional call for improvement of standards, litigation challenging the regulatory process should be used only in exceptional circumstances. The repercussions and ramifications for failure to adhere to the minimal regulatory standards are varied, ranging from fines, revocation, and suspension to actual imprisonment.

Regulations, so says the state of Georgia, are in the “public interest.” See http://www.sos.ga.gov/plb/detective.

In State v. Guardsmark, 25 the court rejected the security defendant’s contention that denial of licenses tended to be an arbitrary exercise. The court, accepting the statute’s stringent licensure requirements and recognizing the need for rigorous investigation of applicants and testing, found no basis to challenge.26 In Guardsmark, the crime cited under Illinois law was “engaging in business as a detective agency without a license.”27 Similarly, State v. Bennett 28 held the defendant liable in a prosecution for “acting as a detective without first having obtained a license.”29

The fact that a security person, business, or industrial concern is initially licensed and granted a certificate of authority to operate does not ensure absolute tenure. Governmental control and administrative review of security personnel and agencies are ongoing processes. Revocation of a license or a certificate to operate has been regularly upheld in appellate reasoning. In Taylor v. Bureau of Private Investigators and Adjustors, 30 suspension of legal authority and license to operate as a private detective was upheld since the evidence clearly sustained a finding that the investigators perpetrated an unlawful entry into a domicile. The private detective’s assertion that the regulation was constitutionally void because of its vagueness was rejected outright.31

License to operate or perform the duties indigenous to the security industry has also been revoked or suspended because of acts committed that involved moral turpitude. In Otash v. Bureau of Private Investigators and Adjustors, 32 the court tackled the definition of moral turpitude and explained that it could be best described as a conduct that was contrary to justice, honesty, and morality. Inclusive within the term would be fraudulent behavior with which the investigator was charged.33 In ABC Security Service, Inc. v. Miller, 34 a plea of nolo contendere to a tax evasion charge was held as sufficient basis for revocation and suspension.35 An opposite conclusion was reached in Kelly v. Tulsa, 36 in which an offense of public drunkenness was found generally not to be an act of moral turpitude that would result in a denial of application, loss, suspension, or revocation of licensing rights.

In summary, it behooves the security industry to stick to the letter of regulatory process. Failure to do so can result in actual criminal convictions or a temporary or permanent intrusion on the right to operate.

Criminal Acts

Both corporations and individuals in the security industry may be convicted of actual criminal code violations, though in the former instance, this is an exceedingly rare event. This liability can attach in either an individual or a vicarious sense. By vicarious we mean that the employer is responsible for the conduct of its employees. Most jurisdictions, however, do impose a higher burden of proof in a case of vicarious liability since “the prosecution must prove that the employer knowingly and intentionally aided, advised or encouraged the employee’s criminal conduct.”37

Visit the Yale Law Journal’s recent treatment of corporate criminal liability at http://www.yalelawjournal.org/images/pdfs/729.pdf.

Other legal issues make difficult a prosecution against corporations for criminal behavior. A broad critique corporate criminal intent can be summarized as follows:

Both queries pose difficult legal dilemmas. While it is common to hear a sort of class warfare critique of the corporate heads of state, this type of “them versus us” will simply not do. To be culpable requires knowledge of the crime and its purpose. In the evolving analysis of corporate crime, a trend toward corporate responsibility has emerged.38 Does a corporate officer and director who has actual knowledge of criminal behavior on the part of subordinates within the corporation bear some level of responsibility? Is a corporation responsible, as principal, for the acts of its agents both civilly and criminally? While “officers may be held criminally responsible on the presumption that it authorized the illegal acts,”39 that judgment will depend on the facts and circumstances of each case.

There are other rationales for imposing criminal culpability on the corporate officers and directors. Criminal charges are regularly brought forth and eventual liability sometimes imposed for failure to uphold the rules and regulatory standards promulgated by government agencies, such as these:

• Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA)

• The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

• National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)

• Environmental Protection Act (EPA)

• Homeland Security Administration (HSA)

Government agencies are empowered to charge and assess criminal penalties and fines. OSHA is the classic federal agency with these sweeping powers.

Review the penalty power and authority under criminal prosecution for OSHA at http://www.ktvu.com/news/23874131/detail.html.

Other common corporate areas of criminality in business crime include securities fraud, antitrust activity, bank fraud, tax evasion, violations against the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), and acts involving bribery, international travel, and business practices.40 Finding corporations criminally responsible for particular actions is not the insurmountable task it once was.

The nature and functions of security practice provides a ripe ground for violations of the criminal law. Evaluate the common scenarios below:

a. A security officer can easily create an apprehension of bodily harm in a detention case.42

b. A security officer, in a crowd control situation, threatens, by a gesture, a private citizen.43

c. An industrial security agent, protecting the physical perimeter, unjustly accosts a person with license and privilege to be on the premises.44

a. A security officer in a retail detention case offensively touches a suspected shoplifter.46

b. A security officer uses excessive force in the restraint of an unruly participant in a demonstration.47

c. A security officer utilizes excessive force to affect an arrest in an industrial location.48

False Arrest or Imprisonment 49

See how a security guard was held responsible under sexual assault statutes at http://www.ktvu.com/news/23874131/detail.html.

a. A security officer is not properly trained in the usage of weapons.

b. A security officer does not possess a license.

c. A security officer inappropriately utilizes weaponry best described as excessive force.

a. A security officer fails to report crimes or take actions necessary to prevent it.

b. Security personnel purposely conceal a major capital offense.

a. Security officers or investigators entice, encourage, or solicit others to perform criminal acts.

c. Security investigator devises a plan that will ensnare a criminal; however such tactics or plan may be construed as a case of entrapment.56