Constitution of a Trust

Chapter 7

Constitution of a Trust

Chapter Contents

Constituting the Trust and the Relationship with Creating a Trust

When is a Trust Completely Constituted?

How a Trust is Completely Constituted

As You Read

Look out for the following key issues:

what is meant by a trust being ‘completely constituted’ and how that has changed from a rigid, objective requirement in the nineteenth century to a more flexible concept in contemporary case law;

what is meant by a trust being ‘completely constituted’ and how that has changed from a rigid, objective requirement in the nineteenth century to a more flexible concept in contemporary case law;

how this topic is underpinned by two equitable maxims: that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift and will not assist a volunteer; and

how this topic is underpinned by two equitable maxims: that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift and will not assist a volunteer; and

how and when a trust can be completely constituted.

how and when a trust can be completely constituted.

Constituting the Trust and the Relationship with Creating a Trust

The essential requirements for the creation of an express trust are that the trust must be both declared and constituted. The requirements to declare a trust have been considered in the previous three chapters. They are that the trust must:

[a] be established by a settlor with mental and physical capacity who must, if the type of trust property requires it (for example, land 1 ad here to any necessary formalities;2

[b] comply with the three certainties. The settlor must intend to declare a trust, that the trust property and the intended beneficial interests in it must be sufficiently certain and that the objects of the trust must also be clear, so that in all cases the trust can be administered by the trustees; 3

[c] adhere to the beneficiary principle which, as a general rule, provides that the trust must be intended to benefit ascertainable human beneficiaries, as opposed to pursue a purpose;4

[d] not infringe the rules against perpetuity. The most significant of these is that the trust property must nowadays vest in its intended beneficiaries within a fixed perpetuity period of 125 years from when the trust comes into effect.5

Constitution of a Trust

Key Learning Point

A trust is constituted when the trust property is transferred from the settlor to the trustee or the settlor holds the property on trust for the beneficiaries. At this point, the trustee becomes the legal owner of the property and holds it on trust for the beneficiary who, of course, has an equitable interest in it.

To understand why a trust must be completely constituted, the relationship between the trust and a gift has to be examined. Equity has two maxims which underpins its treatment of gifts and these also apply to trusts. Those are:

[a] equity will not perfect an imperfect gift; and

[a] equity will not assist a volunteer.

The relationship between a gift and a trust

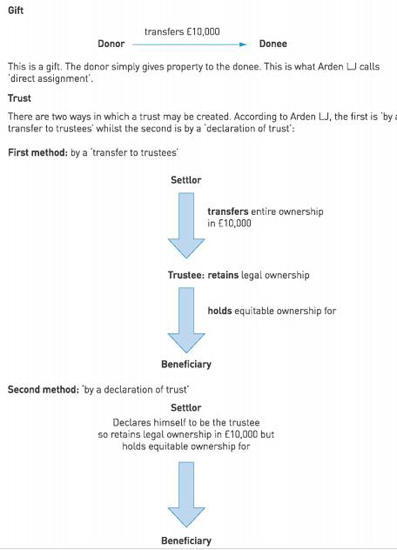

There is a relationship between a gift and a trust, which was explained by Arden LJ in Pennington v Waine:6 ‘[a] gift can be made either by direct assignment, by a transfer to trustees or by a [self] declaration of trust.’7

This dictum can be illustrated by Figure 7.1. In all of the following examples in Figure 7.1, assume that the benefactor wishes to benefit the recipient by the amount of £10,000.

Both the second and third examples in Figure 7.1 involve the settlor setting up a trust. In Arden LJ’s first method of declaring a trust, the property which forms the subject of the gift (£10,000) is transferred to trustees, whereas in her second method, the settlor physically keeps hold of the money himself but on the basis that he declares himself to be a trustee of it.

There are fundamental differences between a gift and a trust. As can be seen from Figure 7.1, a gift involves the donor giving away the property entirely. The donor thus gives away all rights and liabilities in the property to the donee. The donee receives both legal and equitable interests in the property and it becomes his to do with as he generally wishes. The donee is the absolute owner of the property.

A trust, on the other hand, means that whilst the settlor gives away the rights and liabilities in the property to a trustee, the ownership in the property is split. The trustee retains the legal interest and the beneficiary acquires an equitable interest. The trustee then administers the trust for the beneficiary’s benefit. The beneficiary’s rights in the property are limited to the interest he enjoys. If, for instance, the beneficiary has only a life interest in the property, he can enjoy only the income from the trust property for his lifetime. If this was the case in Figure 7.1, the beneficiary would simply receive the interest on the £10,000, rather than the capital sum of £10,000. It is only when a beneficiary becomes entitled to the absolute interest in the trust property that he may seek, provided he is over 18 years of age and mentally capable, to call for the legal interest in the trust property to be transferred to him, merge the legal and equitable interests together and end the trust. This is known as the rule in Saunders v Vautier. 8 vIt is not until that point that the interests will be joined together again.

As trusts are effectively part of the overarching notion of a gift, the equitable maxim that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift applies to all trusts in the same way as making a straightforward gift.

The notion that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift illustrates that equity will not assist everyone on each occasion.9 Equity will not ‘right’ a ‘wrong’. If a trust has not been constituted correctly by a settlor, equity will not finish the job of setting up the trust correctly for them. The trust will not, therefore, have been completely constituted by the settlor and, as such, it will not have been validly created.

Equity will also not assist a volunteer. A volunteer is someone who has not provided any consideration in the transaction. Again, if a settlor has failed to constitute the trust completely, the beneficiary, albeit wholly innocent, will not be allowed to claim any beneficial interest in the trust property. The beneficiary in these circumstances is a volunteer. He has provided no consideration for the transaction and equity will not help him. This appears to flow from part of the general principles of the law of consideration where, to enjoy rights in English law, one must generally have given something to acquire those rights. If the trust is not completely constituted, the beneficiary will have acquired no rights in the trust property and has no basis on which to enforce any such rights.

Constitution of a trust can be broken down into two distinct parts:

When is a trust completely constituted?

When is a trust completely constituted?

How is a trust completely constituted?

How is a trust completely constituted?

When is a Trust Completely Constituted?

As You Read

When you read this part of the chapter, bear in mind:

the fundamental concept that, whilst it is equity that recognises a trust, equity traditionally took the position of an onlooker as opposed to an intervener. Due to its equitable maxims, equity would not assist a defective trust to be created because to do so would infringe the principles of not assisting a volunteer and perfecting an imperfect gift;

the fundamental concept that, whilst it is equity that recognises a trust, equity traditionally took the position of an onlooker as opposed to an intervener. Due to its equitable maxims, equity would not assist a defective trust to be created because to do so would infringe the principles of not assisting a volunteer and perfecting an imperfect gift;

the original — and objective — principle for equity to recognise a trust as having been completely constituted was that the settlor must have done ‘everything necessary’ to transfer the trust property to the trustees;

the original — and objective — principle for equity to recognise a trust as having been completely constituted was that the settlor must have done ‘everything necessary’ to transfer the trust property to the trustees;

how that objective principle has been eroded over the years by the inclusion of a more subjective element which meant that a trust would be constituted if the settlor had done ‘everything in his power’ to create the trust; and

how that objective principle has been eroded over the years by the inclusion of a more subjective element which meant that a trust would be constituted if the settlor had done ‘everything in his power’ to create the trust; and

the more recent development of the Court of Appeal in the key case of Pennington v Waine which appears to develop a new test based on the equitable concept of ‘unconscionability’ to ascertain whether the trust should be seen to be constituted or not. This test seems to result in equity taking an interventionist approach to the constitution of a trust and infringe its two guiding maxims in this area.

the more recent development of the Court of Appeal in the key case of Pennington v Waine which appears to develop a new test based on the equitable concept of ‘unconscionability’ to ascertain whether the trust should be seen to be constituted or not. This test seems to result in equity taking an interventionist approach to the constitution of a trust and infringe its two guiding maxims in this area.

The original test — has the settlor done ‘everything necessary’ to constitute the trust?

Originally, a trust would only be completely constituted when the settlor did everything necessary for the trust property to be transferred to the trustee or to declare himself a trustee. It is only when it could be said that the settlor had taken all necessary steps that the trust could be considered binding on the settlor. What was required was an objective assessment of whether all necessary steps had been taken by the settlor: it is only if they were taken that the trust would have been completely constituted.

This test of whether the settlor had taken all necessary steps to transfer the property to a trustee or to declare himself trustee of it was set out in Milroy v Lord.10

The case concerned an attempt by a resident of New Orleans, Thomas Medley, to set up a trust of 50 of the shares that he owned in the Bank of Louisiana. By a deed dated 2 April 1852, Thomas purported to transfer the shares to his father-in-law, Samuel Lord, so that Samuel would hold the shares on trust for Thomas’ English niece, Eleanor Dudgeon. That meant that the income from the shares — the dividends that the Bank may declare — would be paid to Eleanor. Acting upon this declaration of trust, Thomas gave the share certificates to Samuel. Thomas also gave Samuel both a general power of attorney to act on his behalf in relation to his financial affairs and a specific power of attorney in relation to the dividends which may have been paid by the Bank of Louisiana.

Glossary: Power of Attorney

A power of attorney is a document in which a person (the donor) may appoint another to act on their behalf. The recipient thus stands in the donor’s shoes and acts as if he was the donor.

The power might be general or specific. A general power of attorney enables the recipient to act on the donor’s behalf to manage all of the donor’s affairs. A specific power of attorney is where the donor limits the recipient to acting for him in relation to defined property.

The problem in the case arose because the Bank of Louisiana’s constitution provided that for shares to be transferred into the name of a recipient, the actual share certificates being transferred had to be sent to the Bank. In addition, if a transfer was to be made by a person using a power of attorney, the original power of attorney also had to be lodged with the Bank when the application to transfer the shares was made.

The share certificates were never sent to the Bank. But Samuel Lord acted as though the trust had been properly established. He received the dividends declared by the Bank and paid them over to Eleanor, who by now had married and had become Eleanor Milroy.

Thomas Medley died in 1855. Samuel Lord continued to be willing to honour the trust. It was Thomas’ executor, Mr Otto, who objected to the trust. His argument was that there had been no successful creation of a trust, but instead simply an incomplete gift. This was based on the fact that the share certificates had never been transferred fully into the trustee’s name. All that had occurred was that the settlor had physically handed over the share certificates to the trustee. No legal transfer had taken place. Such a transfer could only be undertaken by the Bank of Louisiana receiving the old share certificates in Thomas Medley’s name and issuing new ones in the name of Samuel Lord. Equity could not perfect this imperfect gift. In addition, Eleanor had provided no consideration for the gift of the shares from her uncle and, as such, she was a volunteer. Equity should not assist a volunteer.

The Court of Appeal agreed with Mr Otto’s argument. The legal ownership in the shares had never passed to Samuel. As the trust had not been constituted, he could not be considered to be a trustee of the shares for Eleanor.

In a well-known dictum, Turner LJ set out when a trust could be considered to be completely constituted:

I take the law of this Court to be well settled, that, in order to render a voluntary settlement valid and effectual, the settlor must have done everything which, according to the nature of the property comprised in the settlement, was necessary to be done in order to transfer the property and render the settlement binding upon him.11

Of course, Samuel Lord had had the benefit of two powers of attorney granted by Thomas Medley under which Samuel could have stepped into Thomas’s shoes and instructed the Bank of Louisiana to transfer the shares into his name. But Samuel had not actually used his authority under either of the powers of attorney to transfer the legal ownership of the shares into his name.

It also made no difference that Samuel had considered himself a trustee of the shares from the moment that the ‘trust’ had been declared by Thomas, by paying the dividends declared by the Bank to Eleanor. This action, too, was irrelevant. It could not ‘right’ the ‘wrong’ of the trust being incompletely constituted by Thomas when it was originally set up.

Equity would not intervene to correct the imperfections of this attempted trust. To do so would infringe its two maxims. The trust had to be completely constituted by the settlor himself for it to be recognised by equity. It would only be completely constituted if the settlor had done ‘everything necessary’ to transfer the legal title in the trust property to the trustee.

Making connections

Look again at the dictum Turner LJ uses for what a settlor must do to create a valid trust in Milroy v Lord. There appear to be two requirements:

[a] the settlor must have done everything ‘necessary to be done’ to transfer the property.This appears to be an objective test, focussing on whether the settlor has done everything physically necessary to transfer the legal title to the trustee; and

[b] the settlor’s actions must be undertaken with the mental element that his actions under-taken should be done with an intention that the trust should becoming binding upon him.

Do you think there is an element of cross-fertilisation with certainty of intention here? At its roots, certainty of intention requires the settlor to display an intention to create a valid trust. It appears that the actions the settlor takes in constituting the trust must be undertaken with a similar intention. Perhaps, however, there is a distinction that can be made. Certainty of intention focuses on an objective intention by the settlor to declare a trust. Intention in constituting the trust requires the settlor to acknowledge that he is, in effect, putting the trust property beyond his own reach. He can do this either by transferring the property physically to a trustee or, alternatively, retaining the legal interest for himself whilst confirming that the beneficial interest is held on trust for the beneficiary.

It is the words of Turner LJ that the settlor must have done ‘everything necessary’ for the trust to be completely constituted and therefore be recognised by equity that the courts have focused on in succeeding cases.

The next significant case in which Turner LJ’s words were examined was Re Fry.12 Ambrose Fry was an American resident who owned shares in Liverpool Borax Ltd. He wanted to give his shares away. He signed transfer documents to transfer 2,000 shares to his son, Sydney and the remainder to Cavendish Investment Trust Ltd (‘the Investment Trust’). The transfer documents eventually found their way to Liverpool Borax Ltd who refused to register the transfer of the shares due to wartime restrictions then in place. Before any shares in the company could be registered in a new owner’s name, the consent of the United Kingdom Treasury had to be obtained. This required Mr Fry to complete and return a number of supplementary docu-ments. Although he did so, he died before the Treasury had given its consent to the transfers of the shares.

The action came before Romer J. Sydney and the Investment Trust argued that Mr Fry had done everything he could possibly have done to affect the transfers of the legal interests in the shares to those two recipients. It was out of Mr Fry’s control that the Treasury had not given its consent. The case could, they argued, be distinguished from Milroy v Lord where the share certificates had never reached the company for them to be transferred into the recipient’s name.

Romer J cited the test propounded by Turner LJ in Milroy v Lord and asked 13 ‘[H]ad every-thing been done which was necessary to put the transferees into the position of the trans-feror?’ He answered the question almost immediately:

[I]t is impossible, in my judgment, to answer the questions other than in the negative. The requisite consent of the Treasury to the transactions had not been obtained, and, in the absence of it, the company was prohibited from registering the transfers. In my opinion, accordingly, it is not possible to hold that, at the date of the testator’s death, the transferees had …. acquired a legal title to the shares in question.….14

As an alternative, Sydney and the Investment Trust argued that Mr Fry had done enough to transfer just the equitable interest in the shares to themselves. Applying Turner LJ’s test again to this argument, Romer J again came to the conclusion that everything necessary to be done to transfer the shares into the names of Sydney and the Investment Trust had not been done. The Treasury’s consent had not been obtained to the transfer taking place. Until that consent was given, ‘everything necessary’ to be done had not been done.

Re Fry appears to be a straightforward application of the principle set out in Milroy v Lord, albeit with a harsh result. Romer J himself confessed that he arrived at his conclusion that there was an imperfect gift ‘with regret’, 15 but found that there was no other logical decision at which he could arrive. Mr Fry had indeed done everything that he could have done: the share certificates had been sent to the company and all necessary forms completed to obtain the Treasury’s consent to the transfer had been completed and despatched to the Treasury. But ‘everything necessary’ to be done had not been done. The Treasury’s consent was the final piece of the jigsaw and that piece had not been put into place.

The case illustrates the objectivity of the test in Milroy v Lord. The number of steps to effect the gift or create the trust that the settlor may have taken are irrelevant. So too is the fact that the settlor may not, as Mr Fry was, be in a position to take any additional steps to complete the gift or constitute the trust. The key is whether ‘everything necessary’ to be done to transfer the legal title in the property to the trustee has been done or not. There are no shades of grey in the answer: just a black-and-white ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If the answer is ‘no’, equity will not step in to help claimants in the place of Sydney and the Investment Trust because equity will not assist a volunteer or perfect the imperfect gift.

The changing concept of ‘everything necessary’

The courts, however, started to shift from this solidly objective approach to whether ‘everything necessary’ to be done to transfer the property had been done to a test which encapsulated a more subjective element to it. The first case in which this shifting approach was seen was Re Rose.16

Counsel for Mrs Rose argued that no tax should be payable on either of the transfers as they were effective when the documents to transfer the shares were executed on 30 March 1943. The difficulty with this argument was that it seemed to run contrary to the principle in Milroy v Lord. According to Turner LJ’s dictum in Milroy v Lord, the transfers would not be effective until ‘everything necessary’ to be done to transfer the property had been done. Until that point, the property would remain in the hands of Mr Rose. ‘Everything necessary’ to be done in the case of a share transfer included the company registering the transfer of the shares from the former to the new owner. This step was not taken until the end of June, by which time the new tax had come into operation.

The Court of Appeal distinguished Milroy v Lord, holding that its ratio did not apply in the present case. Mr Rose’s transfer was always intended to take effect immediately upon its execution on 30 March 1943. As such, the transfer was a way of signalling that he was willing to give away all of his rights in the shares. Between the execution of the transfer and the date of registration of it by the company, Mr Rose became a trustee of the legal interest for the transferees. Evershed MR quoted with approval the decision of Jenkins J in a different case entitled Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose,17 in which he said that the decisions in Milroy v Lord and Re Fry:

turn on the fact that the deceased donor had not done all in his power, according to the nature of the property given, to vest the legal interest in the property in the donee. In such circumstances it is, of course, well settled that there is no equity to complete the imperfect gift.18

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Rose19 was, therefore, to add a twist to the decisions in Milroy v Lord and Re Fry. It made a distinction between gifts made where there were potentially more steps for the donor to take and those where the donor had taken all of the steps that he personally could take. Milroy v Lord and Re Fry were examples of the former situation. In Milroy v Lord, there was more for the donor to do to perfect the transfer: he needed to use the correct form and start the procedure again. In Re Fry, the donor needed to obtain the Treasury’s consent to the proposed transfer of the shares, which he failed to obtain. Jenkins J had explained in Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose that both of those earlier cases had actually focused on whether the donor had done everything he could possibly do to perfect the gift. In that manner, the facts in both Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose and Re Rose could be distinguished from Milroy v Lord and Re Fry. In both of those former cases, the donor had, in fact, done everything he could have done to perfect the gift. The remaining steps needed to be undertaken to perfect the gifts were to be undertaken by other individuals.

The decisions in both Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose and Re Rose brought a subjective element into Turner LJ’s dictum by asking whether the donor had done everything that he could do in order to constitute the gift or trust. If he had done so, then the gift would be perfected or the trust constituted.

In either situation, equity’s maxims of not perfecting an imperfect gift and not assisting a volunteer would still be honoured. There was no need for equity to intervene to perfect the gift or assist the beneficiary as the trust had been completely constituted by the settlor doing everything in his power to transfer the legal title in the property to the trustee.

The difficulty is that such a subjective approach does not sit easily with the decision in either Milroy v Lord or Re Fry. There is no hint in Turner LJ’s test in Milroy v Lord of a subjective element being mentioned: the test seems entirely objective. In Re Fry, it is arguable that Mr Fry had indeed done everything in his power that he could have done to bring about the transfers of the shares, but still Romer J held that the objective test in Milroy v Lord had not been satisfied. Whilst bringing in an element of subjectivity may have led to the ‘right’ result on the facts in both Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose and Re Rose, it is hard to see how it is supported by previous authority. The decision in Re Rose was, however, approved obiter by Lord Wilberforce in Vandervell v IRC 20 where he said that Mr Vandervell had done everything in his power to constitute the trust when he orally directed his trustees to transfer the shares to the Royal College of Surgeons.

The beginnings of equity’s interventionist approach: a new test based on conscience’

A more interventionist approach was started by the decision of the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarani21

The facts revolved around Thakurdas Choithram Pagarani, an Indian man who established a chain of supermarkets around the world. He became very wealthy as a result and, having made provision for his family, wanted to leave much of his money to charity. To do so, he established a charitable foundation, Choithram International Foundation. On the same day, he confirmed orally that he wanted to give all of his wealth to the Foundation, which the Foundation could use for various charitable purposes.

The difficulty arose because the shares and money he instructed to be transferred to the Foundation were not transferred. Mr Pagarani gave instructions to his accountant to undertake the transfers but some of the transfers were never made until after his death. The issue for the court was whether the gifts made by Mr Pagarani could be perfected by those transfers entered into after his death. The High Court of the British Virgin Islands and the Court of Appeal of the British Virgin Islands had both held that Mr Pagarani had made incomplete gifts to his Foundation. The Privy Council disagreed.

In delivering the opinion of the judicial Board, Lord Browne-Wilkinson found that the facts did not fall squarely within the principle of Milroy v Lord. There was no complete gift effected by Mr Pagarani to another recipient nor did he declare himself a trustee of the property for the Foundation. Instead, when Mr Pagarani had expressed the desire to give the money and shares to the Foundation, he intended to give that property to the trustees of the Foundation for them to hold on trust for the Foundation’s charitable purposes. That was the only logical way to construe Mr Pagarani’s words. Lord Browne-Wilkinson explained that the maxim that equity would not assist a volunteer was a simplification of that principle as far as trusts were concerned:

Until comparatively recently the great majority of trusts were voluntary settlements under which beneficiaries were volunteers having given no value. Yet beneficiaries under a trust, although volunteers, can enforce the trust against the trustees. Once a trust relationship is established between trustee and beneficiary, the fact that a beneficiary has given no value is irrelevant.22