Consideration and Other Tests of Enforceability

3

Consideration and Other Tests of Enforceability

Contents

3.4 Consideration or reliance?

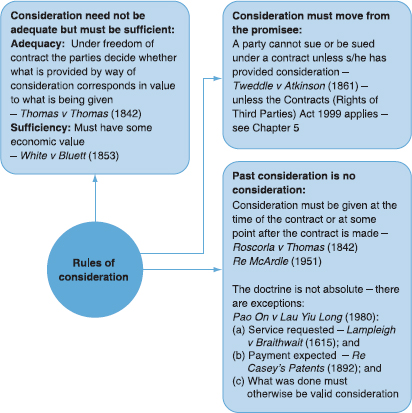

3.7 Consideration need not be ‘adequate’ but must be ‘sufficient’

3.8 Past consideration is no consideration

3.9 Performance of existing duties

3.10 Consideration and the variation of contracts

3.11 The doctrine of promissory estoppel

3.12 Promissory estoppel and consideration

3.13 Promissory estoppel and the part payment of debts

3.15 Alternative tests of enforceability

This chapter is concerned with the issue of the enforceability of promises. How does English law decide whether a promise is to be treated as enforceable by the courts? In investigating this question, the following topics will be considered:

Deeds. These constitute a means of indicating an intention to make an enforceable promise through formal means – that is, putting the promise into a particular type of document.

Deeds. These constitute a means of indicating an intention to make an enforceable promise through formal means – that is, putting the promise into a particular type of document.

Consideration. The doctrine of ‘consideration’ is one of the hallmarks of English contract law. It means, in effect, that promises do not have to take any particular form, or be put in writing, but will be enforceable if there is mutuality in the agreement – both parties bring something to it. Within this doctrine it will be necessary to consider:

Consideration. The doctrine of ‘consideration’ is one of the hallmarks of English contract law. It means, in effect, that promises do not have to take any particular form, or be put in writing, but will be enforceable if there is mutuality in the agreement – both parties bring something to it. Within this doctrine it will be necessary to consider:

What constitutes ‘consideration’? Does it have to have a monetary value?

What constitutes ‘consideration’? Does it have to have a monetary value?

What is meant by the requirement that consideration must be ‘sufficient’, though not necessarily ‘adequate’?

What is meant by the requirement that consideration must be ‘sufficient’, though not necessarily ‘adequate’?

Can an action already performed (past consideration) be consideration for a new promise? (Generally, it cannot.)

Can an action already performed (past consideration) be consideration for a new promise? (Generally, it cannot.)

When will the performance of an existing duty constitute good consideration? The answer will depend on the type of duty.

When will the performance of an existing duty constitute good consideration? The answer will depend on the type of duty.

Promissory estoppel. This doctrine allows a promise unsupported by consideration to be enforced – generally in the context of the variation of an existing contract.

Promissory estoppel. This doctrine allows a promise unsupported by consideration to be enforced – generally in the context of the variation of an existing contract.

Part payment of debts. Generally, part payment of a debt is not good consideration for the remission of the balance, unless promissory estoppel applies.

Part payment of debts. Generally, part payment of a debt is not good consideration for the remission of the balance, unless promissory estoppel applies.

Alternative tests of enforceability. Other jurisdictions use ‘reliance’ as a test of enforceability alongside consideration. To date, English law has made limited use of this test.

Alternative tests of enforceability. Other jurisdictions use ‘reliance’ as a test of enforceability alongside consideration. To date, English law has made limited use of this test.

In the previous chapter, the factors which lead a court to conclude that there is sufficient ‘agreement’ for there to be a binding contract were discussed. In this chapter the focus is on the question of whether all agreements that meet the requirements set out in that chapter will be treated as legally binding. The answer is ‘no’ – agreement is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a binding legal agreement. The English courts have developed other tests to assess the enforceability of agreements. The principal one is the requirement of ‘consideration’, and analysis of this doctrine will form the bulk of this chapter.

In essence the doctrine of consideration requires that both sides to the agreement bring something to the bargain – if the obligations are all on one side, then there will be no ‘consideration’, and probably no contract. This requirement of consideration is a particular characteristic of the common law approach to contractual obligations – it is not found in the same form in jurisdictions whose contract law is not based on English law. It is not without its problems. There are difficulties in deciding, for example, whether doing, or promising to do, something which you are already obliged to do (e.g. under another contract, or as part of a public duty) can be good consideration. Problems also arise in the context of the variation of contracts. To what extent are parties who are involved in an ongoing contractual relationship able to create binding variations to that contract, for example, as a result of changed circumstances? English contract law does not make this process easy. It has also traditionally taken a very strict line on the issue of whether a creditor who promises to forgo the balance of a debt on receipt of part payment can be held to that promise.

In response to these problems, the English courts have developed a concept that is now generally referred to as ‘promissory estoppel’. This is a secondary test of the enforceability of a promise, which does not replace ‘consideration’, but operates in certain specific situations, particularly in relation to the variation of contracts and the part payment of debts, to mitigate the strict application of the common law doctrine. Some analysts of the concept of promissory estoppel go further and argue that it is simply an example of a more wide-ranging test of enforceability which should be regarded as sitting alongside or even replacing consideration. This argument is based around the concept of ‘reasonable reliance’, and suggests that it is in effect where the promisee has reasonably acted in reliance on the promisor’s promise that that promise should be treated as enforceable. This approach has received more acceptance in other common law jurisdictions (e.g. USA, Australia) than it has in the English courts. The issues raised by this analysis are discussed towards the end of this chapter.

The final test of enforceability discussed in this chapter is the ‘deed’. This is a test based on the form of the agreement rather than its content, and can operate to make onesided agreements (such as the promise to make a gift) enforceable, even though there is no consideration for the promise.

These tests of enforceability are not necessarily conclusive of the issue, however. The courts may still insist on asking the question as to whether an agreement that contains offer, acceptance and consideration, was actually intended to be legally binding. The discussion of this overarching concept of ‘intention to create legal relations’ is left to Chapter 4.

The chapter starts with a discussion of ‘deeds’, and then looks at consideration, promissory estoppel and ‘reasonable reliance’.

The ‘deed’ is a way of using the physical form in which an agreement is recorded in order to give it enforceability. The agreement is put in writing and, traditionally, ‘sealed’ by the party or parties to be bound to it. The ‘seal’ could take the form of a wax seal, a seal ‘embossed’ onto the document by a special stamp, or simply the attachment of an adhesive paper seal (usually red).1 Such contracts were also known as ‘contracts under seal’ (in contrast to ‘simple contracts’ which use ‘consideration’ as the test of enforceability).

The formal requirements for making a ‘deed’ are now contained in s 1 of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989.2 There is no longer any requirement that the document should be sealed.3 The document must, however, make it clear ‘on its face’ that it is intended to be a deed, and it must be ‘validly executed’ by the person making it or the parties to it.4 ‘Valid execution’ for an individual means that the document must be signed in the presence of a witness who attests to the signature.5 In addition there is a requirement of delivery – the document must be ‘delivered as a deed by [the person executing it] or a person authorised to do so on his behalf’.6 For a company incorporated under the Companies Acts, the position is governed by ss 44 and 46 of the Companies Act 2006. The ‘execution’ of a document by a company can take effect either by the affixing of its common seal,7 or by being signed by a director and the secretary of the company, or by two directors.8 For a document executed by a company to be a deed, it simply needs to make clear on its face that this is what is intended by whoever created it.9 It will take effect as a deed upon delivery, but unless a contrary intention is proved, it is presumed to be delivered upon being executed.10 In OTV Birwelco Ltd v Technical and General Guarantee Co Ltd,11 it was held that a deed was validly executed where a company had used its trading name rather than its registered name; nor did it render the deed unenforceable that the seal used was engraved with the trading name rather than the registered name (contrary to s 350 of the Companies Act 1985 – now replaced by s 45 of the Companies Act 2006). Non-compliance with this section rendered the company concerned liable to a fine, but had no automatic effect on the validity of the deed.

If the parties to an agreement have taken the trouble to put it into the form of a deed, following the requirements laid down by s 1 of the 1989 Act (or s 44 of the Companies Act 2006), the courts will assume that it was their intention to create a legally binding agreement, and will not inquire into whether the other main test of enforceability (that is, ‘consideration’) is present. As will be seen below, the characteristic of the modern doctrine of consideration is that there is mutuality in the arrangement, with something being supplied by both parties to the agreement. This is not necessary in an agreement which is put into the form of a deed. Where, therefore, a transaction is ‘one-sided’ with only one party giving, and the other party receiving all the benefit without providing anything in exchange, the deed is one certain way of making the arrangement enforceable.

3.3.1 IN FOCUS: PRACTICAL USE OF DEEDS

Deeds may be used even where the transaction is supported by consideration.12 This has traditionally been done in relation to complex contracts in the engineering and construction industries. This is probably because, by virtue of the Limitation Act 1980, the period within which an action for breach of an obligation contained in a deed is 12 years,13 whereas for a ‘simple’ contract it is only six years.14 The longer period is clearly an advantage in a contract where problems may not become apparent for a number of years. The practice of ‘sealing’ a document is also still used, even though it is no longer necessary even for a company. It may in some circumstances serve to make it clear that the document is intended to be a ‘deed’. It does not in itself, however, make the transactions concerned any more or less enforceable.

For contracts that are not made in the form of a deed, ‘consideration’ is generally used as the test of enforceability, and it is to this that we now turn.

The doctrine of consideration is one of the characteristics of classical English contract law. This provides that no matter how much the parties to a ‘simple contract’ may wish it to be legally enforceable, it will not be so unless it contains ‘consideration’. What does the word mean in this context? It is important to note that it does not have its ordinary, everyday meaning. It is used in a technical sense. Essentially, it refers to what one party to an agreement is giving, or promising, in exchange for what is being given or promised from the other side. So, for example, in a contract where A is selling B 10 bags of grain for £100, what is the consideration? A is transferring the ownership of the grain to B. In consideration of this, B is paying £100. Or, to look at it the other way round, B is paying A £100. In consideration for this, A is transferring to B the ownership of the grain. From this example it will be seen that there is consideration on both sides of the agreement. It is this mutuality which makes the agreement enforceable. If B simply agreed to pay A £100, or A agreed to give B the grain, there would be no contract. The transaction would be a gift and would not be legally enforceable.

The history of the development of this doctrine is a matter of controversy. Some writers have argued that a study of the history of the English law of contract shows that ‘consideration’, when first referred to by the judges, meant simply a ‘reason’ for enforcing a promise.15 According to this view, such ‘reasons’ could be wide-ranging. It was only in the late eighteenth century at the earliest,16 and probably not until the production of the first contract textbooks in the second half of the nineteenth century,17 that the doctrine of consideration came to be regarded as consisting of the fairly rigid set of rules which it is now generally regarded as comprising. The approach here is to deal with the doctrine as it currently appears to be, but to keep in mind that there are alternative tests of contract enforceability. The main alternative is the concept of ‘reasonable reliance’. This will be discussed more fully at the end of this chapter,18 but a brief outline will be given here, in order to put the discussion of consideration in a proper perspective.

The concept of reliance as the basis for enforceability is that it is actions, and reliance on those actions, that creates obligations, rather than an exchange of promises (as under the classical doctrine of consideration). Thus, the window cleaner who, having checked that you want your windows cleaned, then does the work, does so in reliance on the fact that you will pay for what has been done. This is suggested to be a more accurate way of analysing many contractual situations than in terms of the mutual exchanges of promises, which forms the paradigmatic contract under the classical model.19 Once this principle is accepted, it then opens the door to enforcing agreements where there is nothing that the classical law would recognise as ‘consideration’, provided that there is ‘reasonable reliance’. This is accepted to a greater or lesser extent by many common law jurisdictions,20 but has only received limited support to date by the English courts – though some recent decisions purportedly based on ‘consideration’ can be argued to be more accurately concerned with ‘reliance’.21

We will return towards the end of the chapter to consider further questions about the theoretical basis of consideration,22 and whether it is developing in a way which may perhaps have links to its historical origins. At that point it will also be worth looking more generally at the question of whether consideration still retains its dominant position at the heart of the English law of contract, or whether the growth in situations where promises may be enforceable in the absence of consideration means that its role needs further reassessment. In the meantime, in the discussion of consideration in the following sections, the tension between the classical theory and the more modern trends towards reliance-based liability needs to be kept in mind, and will be highlighted at various points.

It is sometimes said that consideration requires benefit and detriment. The often quoted, but not particularly helpful, definition of consideration contained in Currie v Misa23 refers to these elements:

A valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either in some right, interest, profit or benefit accruing to one party or some forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility, given, suffered or undertaken by the other.

In other words, what is provided by way of consideration should be a benefit to the person receiving it, or a detriment to the person giving it. Sometimes, both are present. For example, in the contract concerning the sale of grain discussed in the previous section, B is suffering a detriment by paying the £100, and A is gaining a benefit. B is gaining a benefit in receiving the grain, A is suffering a detriment by losing it. In many cases, there will thus be both benefit and detriment involved, but it is not necessary that this should be the case. Benefit to one party, or detriment to the other, will be enough. Suppose that A agrees to transfer the grain, if B pays £100 to charity. In this case, B’s consideration in paying the £100 is a detriment to B, but not a benefit to A. Nevertheless, B’s act is good consideration, and there is a contract. In theory, it is enough that the recipient of the consideration receives a benefit, without the giver suffering a detriment. It is difficult, however, to think of practical examples of a situation of this kind, given that the traditional rule is that consideration must move from the promisee.

The discussion so far has been in terms of acts constituting consideration. It is quite clear, however, that a promise to act can in itself be consideration. Lord Dunedin, in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v Selfridge & Co Ltd,24 for example, approved the following statement from Pollock, 1902 (emphasis added):

An act or forbearance of the one party, or the promise thereof, is the price for which the promise of the other is bought, and the promise thus given for value is enforceable.

Suppose, then, continuing the example used above, that on Monday, A promises that he will deliver and transfer the ownership of the grain to B on the following Friday; and B promises, again on Monday, that when it is delivered she will pay £100. There is no doubt that there is a contract as soon as these promises have been exchanged, so that if on Tuesday B decides that she does not want the grain and tries to back out of the agreement, she will be in breach of contract. But where is the consideration? On each side, the giving of the promise is the consideration. A’s promise to transfer the grain is consideration for B’s promise to pay for it, and vice versa. The problem is that this does not fit easily with the idea of benefit and detriment. A’s promise is only a benefit to B, and a detriment to A, if it is enforceable. But it will only be enforceable if it is a benefit or a detriment. The argument is circular, and cannot therefore explain why promises are accepted as good consideration.25 There is no easy answer to this paradox,26 but the undoubted acceptance by the courts of promises as good consideration casts some doubt on whether benefit and detriment can truly be said to be essential parts of the definition of consideration. It may be that the concept simply requires the performance of, or the promise to perform, some action which the other party would like to be done. This approach ignores the actual or potential detriment. Alternatively, if it is thought that the idea of benefit and detriment is too well established to be discarded, the test must surely be restated so that consideration is provided where a person performs an act which will be a detriment to him or her or a benefit to the other party, or promises to perform such an act. On this analysis, benefit and detriment are not so much essential elements of consideration, as necessary consequences of its performance.

Figure 3.1

The view that the element of ‘mutuality’ is the most important aspect of the doctrine of consideration is perhaps supported by the fact that the courts will not generally inquire into the ‘adequacy’ of consideration. ‘Adequacy’ means the question of whether what is provided by way of consideration corresponds in value to what it is being given for. This is to be distinguished from the question of whether consideration is ‘sufficient’, in the sense that what is being offered in exchange is recognised by the courts as being in law capable of amounting to consideration. This issue is discussed further below.

Looking first, however, at the question of adequacy, the reluctance of the courts to investigate this means, for example, that if I own a car valued at £20,000, and I agree to sell it to you for £1, the courts will treat this as a binding contract.27 Your agreement to pay £1 provides sufficient consideration for my transfer of ownership of the car, even though it is totally ‘inadequate’ in terms of its relationship to the value of the car.

This aspect of consideration was confirmed in Thomas v Thomas.28

Key Case Thomas v Thomas (1842)

Facts: The testator, Mr Thomas, before his death, expressed a wish that his wife should have for the rest of her life the house in which they had lived. After his death, his executors made an agreement with Mrs Thomas to this effect, expressed to be ‘in consideration’ of the testator’s wishes. There was also an obligation on Mrs Thomas to pay £1 per year, and to keep the house in repair. It was argued that there was no contract here, because Mrs Thomas had provided no sufficient consideration.

Held: The statement that the agreement was ‘in consideration’ of the testator’s wishes was not using ‘consideration’ in its technical contractual sense, but was expressing the motive for making the agreement. The actual ‘consideration’ was the payment of £1 and the agreement to keep the house in repair. Either of these was clearly recognised as good consideration, even though the payment of £1 could in no way be regarded as anything approaching a commercial rent for the property.

This approach to the question of ‘adequacy’ may be seen as flowing from a ‘freedom of contract’ approach. The parties are regarded as being entitled to make their agreement in whatever form, and on whatever terms they wish. The fact that one of the parties appears to be making a bad bargain is no reason for the court’s interference. They are presumed to be able to look after themselves, and it is only if there is some evidence of impropriety that the court will inquire further.29 The mere fact that there is an apparent imbalance, even a very large one, in the value of what is being exchanged under the contract, will not in itself be the catalyst for such further inquiry. It might be thought that with the decline of the dominance of ‘freedom of contract’ during the twentieth century, this aspect of the doctrine of consideration might have also weakened, but there is no evidence of this from the case law.30

Turning to the question of the ‘sufficiency’ of consideration (that is, whether what is offered is capable of amounting to consideration), in coming to its conclusion in Thomas v Thomas, the court pointed out that consideration must be ‘something which is of some value in the eye of the law’.31 This has generally been interpreted to mean that it must have some economic value. Thus, the moral obligation which the executors might have felt, or been under, to comply with the testator’s wishes would not have been sufficient. An example of the application of this principle may perhaps be found in the case of White v Bluett.32 A father promised not to enforce a promissory note (that is, a document acknowledging a debt) against his son, provided that the son stopped complaining about the distribution of his father’s property. It was held that this was not an enforceable agreement, because the son had not provided any consideration. As Pollock CB explained:33

The son had no right to complain, for the father might make what distribution of his property he liked; and the son’s abstaining from what he had no right to do can be no consideration.

The courts have not been consistent in this approach, however. In the American case of Hamer v Sidway,34 a promise not to drink alcohol, smoke tobacco or swear was held to be good consideration, and in Ward v Byham35 it was suggested that a promise to ensure that a child was happy could be good consideration.

Even in cases which have a more obvious commercial context, the requirement of economic value does not seem to have been applied very strictly. An example is Chappell & Co v Nestlé Co Ltd.36

Key Case Chappell & Co v Nestlé Co Ltd (1960)

Facts: This case arose out of a ‘special offer’ of a familiar kind, from Nestlé, under which a person who sent in three wrappers from bars of their chocolate could buy a record, Rockin’ Shoes, at a special price. For the purpose of the law of copyright, it was important to decide whether the chocolate wrappers were part of the consideration in the contract to buy the record.

Held: The House of Lords decided that the wrappers were part of the consideration, despite the fact that it was established that they were thrown away by Nestlé, and were thus of no direct value to them.

The only economic value in the wrappers that it is at all possible to discern is that they represented sales of chocolate bars, which was obviously the point of Nestlé’s promotion. This is, however, very indirect, particularly as there was no necessity for the person who bought the chocolate to be the same as the person who sent the wrappers in. In contrast to this decision, the House of Lords held in Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale Ltd37 that gambling chips, given in exchange for money by a gambling club to its customers, did not constitute valuable consideration. The case concerned an attempt to recover £154,693 of stolen money which had been received in good faith by the club from a member of the club. If ‘good consideration’ for the money had been given by the club, then the money could not be recovered by the true owner. What the club had given for the money were plastic chips which could be used for gambling, or to purchase refreshments in the club. Any chips not lost or spent could be reconverted to cash. This was not regarded by the House of Lords as providing consideration for the money, but simply as a mechanism for enabling bets to be made without using cash. If the contract had been one for the straightforward purchase of the chips, then presumably the transfer of ownership of the chips to the member would have been good consideration, since the club presumably made such a contract when it bought the chips from the manufacturer or wholesaler. The fact that the amount of money paid by the member far exceeded the intrinsic value of the chips (that is, their value as pieces of coloured plastic, rather than as a means of gambling) would have been irrelevant under the principle discussed above relating to the adequacy of consideration. The conclusion that on the facts before the court the chips themselves were not consideration must, therefore, be regarded as being governed by the situation in which they were provided. The contractual relationship between the member and the club is probably best analysed in the way suggested by Lord Goff, who took the view that the transaction involved a unilateral contract under which the club issuing the chips agreed to accept them as bets or, indeed, in payment for other services provided by the club. The case should not be treated as giving any strong support to the view that consideration must have some economic value.

An example of the lengths to which the courts will sometimes go to identify consideration is De La Bere v Pearson.38 The plaintiff had written to a newspaper which invited readers to write in for financial advice. Some of the readers’ letters, together with the newspaper’s financial editor’s advice, were published. The plaintiff received and followed negligently given advice which caused him loss. Since the tort of negligent misstatement was at the time unrecognised, the plaintiff had to frame his action in contract. But where was the consideration for the defendants’ apparently gratuitous advice? The purchase of the newspaper was one possibility, but there was no evidence that this was done in order to receive advice. The only other possibility, which was favoured by the court, was that the plaintiff, by submitting a letter, had provided free copy which could be published. This was thought to be sufficient consideration for the provision of the advice, which it would be implied should be given with due care.

For Thought

Does this decision mean that those who run phone-in radio programmes where advice may be given should always issue disclaimers, to protect themselves from being sued by dissatisfied recipients of advice?

De La Bere v Pearson is a case that might well have been dealt with better by using ‘reasonable reliance’ as a basis for liability. If it was reasonable in all the circumstances for the plaintiff to rely on the defendant’s advice, and he did so to his detriment, he should be able to recover compensation.39 Such an approach would be more satisfactory than the technical arguments about consideration in which the court was obliged to indulge in applying the classical theory.

The sufficiency of consideration has more recently been considered in a different context in Edmonds v Lawson.40 The Court of Appeal was considering whether there was a contract between a pupil barrister and her chambers in relation to pupillage. The problem was to identify what benefit the pupil would supply to her pupilmaster or to chambers during the pupillage. The court noted that the pupil was not obliged to do anything which was not conducive to her own professional development. Moreover, where work of real value was done by the pupil, whether for the pupilmaster or anyone else, there was a professional obligation to remunerate the pupil. This led the court to the conclusion that there was no contract between the pupil and pupilmaster, because of lack of consideration. It came to a different view, however, as to the relationship between the pupil and her chambers. Chambers have an incentive to attract talented pupils who may compete for tenancies (and thus further the development of the chambers). Even if they do not remain at the chambers (for example, by moving to another set, or working in the employed bar or overseas), there may be advantages in the relationships which will have been established. The conclusion was that:41

The court was therefore prepared to accept the general benefits to chambers in the operation of a pupillage system as being sufficient to amount to consideration in relation to contracts with individual pupils, without defining with any precision the economic value of such benefits.

As these cases illustrate, the requirement of ‘economic value’ is not particularly strict. Indeed, in the overall pattern of decisions in this area, it is the case of White v Bluett (1853) which looks increasingly out of line. The flexibility which the courts have adopted in this area has led Treitel to refer to the concept of ‘invented consideration’.42 This arises where the courts ‘regard an act or forbearance as the consideration for a promise even though it may not have been the object of the promisor to secure it’; or ‘regard the possibility of some prejudice to the promisee as a detriment without regard to the question of whether it has in fact been suffered’.43 This analysis has been strongly criticised by Atiyah as an artificial means of reconciling difficult decisions with ‘orthodox’ doctrine on the nature of consideration.44 He argues that if something is treated by the courts as consideration, then it is consideration, and that Treitel’s ‘invented’ consideration is in the end the same thing as ordinary consideration. If some cases do not, as a result, fit with orthodox doctrine, then it is the doctrine which needs adjusting.45

As we have seen, the issue of the ‘sufficiency’ of consideration looks to the type, or characteristics, of the thing which has been done or promised, rather than to its value. In addition to the requirement of economic value, which as we have seen is applied flexibly, there are two other issues which must be considered here. The first is the question of so-called ‘past consideration’. The second is whether the performance of, or promise to perform, an existing duty can ever amount to consideration.

Consideration must be given at the time of the contract or at some point after the contract is made. It is not generally possible to use as consideration some act or forbearance which has taken place prior to the contract. Suppose that I take pity on my poverty-stricken niece and give her my old car. If the following week she wins £10,000 on the Lottery, and says she will now give me £500 out of her winnings as payment for the car, is that promise enforceable? English law says no, because I have provided no consideration for it. My transfer of the car was undertaken and completed without any thought of payment, and before my niece made her promise. This is ‘past consideration’ and so cannot be used to enforce an agreement. A case which applies this basic principle is Roscorla v Thomas.46 The plaintiff had bought a horse from the defendant. The defendant then promised that the horse was ‘sound and free from vice’, which turned out to be untrue. The plaintiff was unable to sue on this promise, however, since he had provided no consideration for it. The sale was already complete before the promise was made.

A more recent example of the same approach is Re McArdle.47

Facts: William McArdle left a house to his sons and daughter. One of the sons was living in the house, and he and his wife carried out various improvements to it. His wife then got each of his siblings to sign a document agreeing to contribute to the costs of the work. The document was worded in a way which read as though work was to be done, and that when it was completed, the other members of the family would make their contribution out of their share of William McArdle’s estate. Held: The document did not truly represent the facts. If it had done so, then, of course, it would have constituted a binding contract, but, as Jenkins LJ pointed out:48

The true position was that, as the work had in fact all been done and nothing remained to be done … at all, the consideration was a wholly past consideration, and therefore the beneficiaries’ agreement for the repayment … of the £488 out of the estate was nudum pactum, a promise with no consideration to support it.

This being so, the agreements to pay were unenforceable.

3.8.1 THE COMMON LAW EXCEPTIONS

The doctrine of past consideration is not an absolute one, however. The courts have always recognised certain situations where a promise made subsequent to the performance of an act may nevertheless be enforceable. The rules derived from various cases have now been restated as a threefold test by the Privy Council in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long.49 Lord Scarman, delivering the opinion of the Privy Council, recognised that:50

… an act done before the giving of a promise to make a payment or to confer some other benefit can sometimes be consideration for the promise.

For the exception to apply, the following three conditions must be satisfied. First, the act must have been done at the promisor’s request. This derives from the case of Lampleigh v Braithwait,51 where the defendant had asked the plaintiff to seek a pardon for him in relation to a criminal offence which he had committed. After the plaintiff had made considerable efforts to do this, the defendant promised him £100 for his trouble. It was held that the promise was enforceable. Second, the parties must have understood that the act was to be rewarded either by a payment or the conferment of some other benefit. In Re Casey’s Patents,52 the plaintiff had managed certain patents on behalf of the defendants. They then promised him a one-third share in consideration of the work which he had done. It was held that the plaintiff must always have assumed that his work was to be paid for in some way. The defendants’ promise was simply a crystallisation of this reasonable expectation and was therefore enforceable.

The effect of these tests is that consideration will be valid to support a later promise, provided that all along there was an expectation of reward. It is very similar to the situation where goods or services are provided without the exact price being specified. As we have seen, the courts will enforce the payment of a reasonable sum for what has been provided. That is, in effect, also what they are doing in situations falling within the three tests outlined above. It is an example of the courts implementing what they see as having been the intention of the parties, taking an approach based on third party objectivity.53

It can also be argued that the whole common law doctrine of ‘past consideration’ could be dealt with more simply, and with very similar results, by an overall principle of ‘reasonable reliance’. Thus, in Re McArdle, the son did the work before any promise was made by his siblings. He did not, therefore, act in reliance on their promises. By contrast, in Lampleigh v Braithwait and Re Casey’s Patents, the work was done in reliance on a promise or expectation of payment. The advantage of an analysis on these lines is that it involves one general principle governing all situations, rather than stating a general rule and then making it subject to exceptions. This is not, so far, however, the approach of the English courts, which prefer to adhere to at least the form of classical theory.

3.8.2 EXCEPTIONS UNDER STATUTE

Two statutory exceptions to the rule that past consideration is no consideration should be briefly noted. First, s 27 of the Bills of Exchange Act 1882 states that:

Valuable consideration for a bill [of exchange] may be constituted by (a) any consideration sufficient to support a simple contract, (b) an antecedent debt or liability.

The inclusion of (b) indicates that an existing debt, which is not generally good consideration for a promise,54 can be so where it is owed by a person receiving the benefit of a promise contained in a bill of exchange.

The second statutory exception is to be found in s 29(5) of the Limitation Act 1980, which provides that where a person liable or accountable for a debt55 acknowledges it, the right ‘shall be treated as having accrued on and not before the date of the acknowledgment’. The acknowledgment must be in writing and signed by the person making it.56 The relevance of this provision to the current discussion is that if the acknowledgment is in the form of a promise,57 it will have the effect of extending the limitation period for recovery of the debt, even though no fresh consideration has been given. The statute is thus in effect allowing ‘past consideration’ to support a new promise.

Can the performance of, or the promise to perform, an act which the promisor is already under a legal obligation to carry out, ever amount to consideration? Three possible types of existing obligation may exist, and they need to be considered separately. These are first, where the obligation which is alleged to constitute consideration is already imposed by a separate public duty; second, where the same obligation already exists under a contract with a third party; and, third, where the same obligation already exists under a previous contract with the same party by whom the promise is now being made.

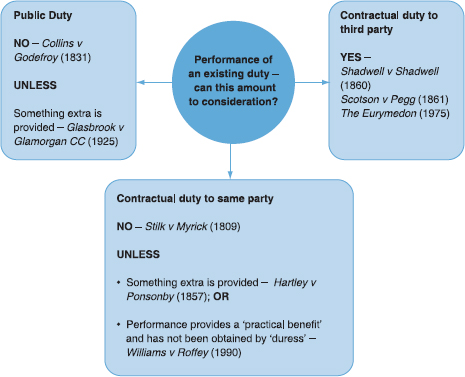

Figure 3.2

3.9.1 EXISTING DUTY IMPOSED BY LAW: PUBLIC POLICY

Where the promisee is doing something that is a duty imposed by some public obligation, there is a reluctance to allow this to be used as the basis of a contract. It would clearly be contrary to public policy if, for example, an official with the duty to issue licences to market traders was allowed to make enforceable agreements under which the official received personal payment for issuing such a licence. The possibilities for corruption are obvious. It would be equally unacceptable for the householder whose house is on fire to be bound by a promise of payment in return for putting out the fire made to a member of the fire brigade. The difficulty is in discerning whether the refusal to enforce such a contract is on the basis that it is vitiated as being contrary to public policy,58 or because the consideration which has been provided is not valid. The case law provides no clear answer. The starting point is Collins v Godefroy.59 In this case, a promise had been made to pay a witness, who was under an order to attend the court, six guineas for his trouble. It was held that this promise was unenforceable, because there was no consideration for it. This seems to have been on the basis that the duty to attend was ‘a duty imposed by law’.

In cases where the possibilities for extortion are less obvious, there has been a greater willingness to regard performance of an existing non-contractual legal duty as being good consideration, though it must be said that the clearest statements to that effect have come from one judge, that is, Lord Denning. In Ward v Byham,60 the duty was that of a mother to look after her illegitimate child. The father promised to make payments, provided that the child was well looked after and happy, and was allowed to decide with whom she should live. Only the looking after of the child could involve the provision of things of ‘economic value’ sufficient to amount to consideration, but the mother was already obliged to do this. Lord Denning had no doubt that this could, nevertheless, be good consideration:61

I have always thought that a promise to perform an existing duty, or the performance of it, should be regarded as good consideration, because it is a benefit to the person to whom it is given.

The other two members of the Court of Appeal were not as explicit as Lord Denning, and seem to have regarded the whole package of what the father asked for as amounting to good consideration. This clearly went beyond the mother’s existing obligation, but, as has been pointed out,62 did not involve anything of economic value. So, on either basis, the decision raises difficulties as regards consideration. Lord Denning returned to the same point in Williams v Williams,63 which concerned a promise by a husband to make regular payments to his wife, who had deserted him, in return for her promise to maintain herself ‘out of the said weekly sum or otherwise’. The question arose as to whether this provided any consideration for the husband’s promise, since a wife in desertion had no claim on her husband for maintenance, and was in any case bound to support herself. Once again, Lord Denning commented:64

… a promise to perform an existing duty is, I think, sufficient consideration to support a promise, so long as there is nothing in the transaction which is contrary to the public interest.

Once again, the other members of the Court of Appeal managed to find in the wife’s favour without such an explicit statement. What this quote from Lord Denning makes clear, however, is that he regards the rule against using an existing non-contractual duty as consideration as being based on the requirements of the public interest, which would arise in the examples using government officials of one kind or another. Where this element is not present, however, he is saying that an existing duty of this kind can provide good consideration.

The law on this issue remains uncertain but, in view of the position in relation to duties owed to third parties, and recent developments in relation to duties already owed under a contract with the promisor (that is, in the case of Williams v Roffey65), it seems likely that Lord Denning’s approach would be followed. There does not seem to be any general hostility in English law to the argument that an existing duty can provide good consideration. In other words, performance of, or the promise to perform, an existing ‘public’ duty imposed by law can be good consideration, provided that there is no conflict with the public interest.

Is this an area in which a ‘reliance’-based approach might provide a better answer? It would still be necessary to exclude situations where public policy suggests that payments should not be enforceable. In other situations where there is a ‘duty’, the question would still arise as to whether the claimant’s actions were undertaken in reliance on the defendant’s promise, or simply because they were under a duty. This would be a question of fact, however, rather than law.

3.9.2 PUBLIC DUTY: EXCEEDING THE DUTY

Whatever the correct answer to the above situation, it is clear that if what is promised or done goes beyond the existing duty imposed by law, then it can be regarded as good consideration. This applies whatever the nature of the duty, so that even as regards public officials, consideration may be provided by exceeding their statutory or other legal obligations. The point was confirmed in Glasbrook Bros v Glamorgan CC.66

Key Case Glasbrook Bros v Glamorgan CC (1925)

Facts: In the course of a strike at a coal mine, the owners of the mine were concerned that certain workers who had the obligation of keeping the mines safe and in good repair should not be prevented from carrying out their duties. They sought the assistance of the police in this. The police suggested the provision of a mobile group, but the owners insisted that the officers should be billeted on the premises. For this, the owners promised to pay. Subsequently, however, they tried to deny any obligation to pay, claiming that the police were doing no more than fulfilling their legal obligation to keep the peace.

Held: The House of Lords held that the provision of the force billeted on the premises went beyond what the police were obliged to do. Viscount Cave LC accepted that if the police were simply taking the steps which they considered necessary to keep the peace, etc., members of the public, who already pay for these police services through taxation, could not be made to pay again. Nevertheless, if, at the request of a member of the public, the police provided services which went beyond what they (the police) reasonably considered necessary, this could provide good consideration for a promise of payment.

This rule is now generally accepted, so that wherever the performance of an act goes beyond the performer’s public duty, it will be capable of providing consideration for a promise.

In relation to the police, however, the position is now dealt with largely by statute. Section 25(1) of the Police Act 1996 states that:

The chief officer of a police force may provide, at the request of any person, special police services at any premises or in any locality in the police area for which the force is maintained, subject to the payment to the police authority of charges on such scales as may be determined by that authority.

In Harris v Sheffield Utd FC,67 which concerned the provision of policing for football matches, the court confirmed the approach taken in Glasbrook. Moreover, in applying the predecessor to s 25 of the Police Act 1996,68 the Court of Appeal held that if a football club decided to hold matches and requested a police presence, such presence could constitute ‘special police services’ even though it did not go beyond what the police felt was necessary to maintain the peace. A ‘request’ for a police presence could be implied if police attendance was necessary to enable the club to conduct its matches safely. The football club was therefore held liable to pay for the services provided. If, however, the club disagrees with the police as to the level of policing required, and specifically asks for a lower level of attendance, there will be no implied request for the higher level of provision that the police may think appropriate. The club will only be liable to pay for the services which it actually requested. This was the view of the Court of Appeal in Chief Constable for Greater Manchester v Wigan Athletic AFC Ltd.69

It seems, therefore, that the holding of an ‘event’ to which the public are invited, but which cannot safely be allowed to go ahead without a police presence, will lay the organisers open to paying for ‘special services’. To that extent, the position has gone beyond that which applied in Glasbrook, in that under the statute the police can receive payment even though they are only doing what they feel is necessary to keep the peace. This clearly applies to sporting events and entertainments (such as music festivals). It is unclear whether it could apply to political rallies or demonstrations, although Balcombe LJ stated that, in his view, political events fell into a different category:70

I do not accept that the cases are in pari materia and I do not consider that dismissal of this appeal poses any threat to the political freedoms which the citizen of this country enjoys.

Nevertheless, the effect of the interpretation of the statutory provisions adopted in Harris means that in certain circumstances the police can receive payment for doing no more than carrying out their duty to maintain public order.

3.9.3 EXISTING CONTRACTUAL DUTY OWED TO THIRD PARTY

If a person is already bound to perform a particular act under a contract, can the performance of, or promise to perform, this act amount to good consideration for a contract with someone else? Suppose that A is contractually bound to deliver 5,000 widgets to B by 1 June. B is to use these widgets in producing items which he has contracted to supply to C. C therefore has an interest in A performing the contract for delivery to B on time, and promises A £5,000 if the goods are delivered by 1 June. Can A enforce this payment by C if the goods are delivered to B on the date required? Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the courts have given a clear positive answer to this question. In other words, they have been quite happy to accept that doing something which forms part, or indeed the whole, of the consideration in one contract can perfectly well also be consideration in another contract.

The starting point is the case of Shadwell v Shadwell.71

Key Case Shadwell v Shadwell (1860)

Facts: An uncle promised his nephew, who was about to get married, the sum of £150 a year until the nephew’s annual income as a barrister reached 600 guineas. The uncle paid 12 instalments on this basis, but then he died, and the payments ceased. The nephew sued the uncle’s estate for the outstanding instalments, to which the defence was raised that the nephew had provided no consideration. The nephew put forward his going through with the marriage as consideration. At the time, a promise to marry was enforceable against the man making such a promise.72

Held: The majority of the court had no doubt that performance of the marriage contract could be used as consideration for the uncle’s promise, on the basis that that promise was in effect an inducement to the nephew to go through with the marriage. Erle CJ recognised that there was some delicacy involved in categorising the nephew’s marriage to the woman of his choice as a ‘detriment’ to him, but nevertheless considered that in financial terms it might well be. He put the issue in these terms:73

… do these facts shew a loss sustained by the plaintiff at his uncle’s request? When I answer this in the affirmative, I am aware that a man’s marriage with the woman of his choice is in one sense a boon, and in that sense the reverse of a loss: yet, as between the plaintiff and the party promising to supply an income to support the marriage, it may well be also a loss. The plaintiff may have made a most material change in his position, and induced the object of his affection to do the same, and may have incurred pecuniary liabilities resulting in embarrassments which would be in every sense a loss if the income which had been promised should be withheld.

Moreover, a marriage, while primarily affecting the parties to it, ‘may be an object of interest to a near relative, and in that sense a benefit to him’. Thus, not only was going through with the marriage a ‘detriment’ to the nephew, it was also a ‘benefit’ to his uncle. On this basis, there was no doubt that it could constitute good consideration for the promise to pay the annuity.

3.9.4 IN FOCUS: AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW OF SHADWELL

The dissenting judge in Shadwell, Byles J, was not convinced that the uncle’s promise was made on the basis that it was in return for the nephew getting married. There is some force in this view of the facts,74 and a possible construction of the case is that the majority of the court was ‘inventing’ consideration, because it felt that the nephew had relied on his uncle’s promise. If the nephew had organised his affairs on the basis that he would continue to receive the payment – a reliance reinforced by the fact that payments had been made regularly over 12 years – then it would be unfair to withdraw it.75 Such an analysis is relevant to the general issue of ‘reliance’ as an alternative to consideration, as discussed at the end of this chapter. It is, however, the majority view in Shadwell v Shadwell that has been accepted by later courts, and the case is therefore taken as authority for the proposition that performance of a contractual obligation owed to a third party can be good consideration to found a contract with another promisor.

3.9.5 DUTY TO THIRD PARTY: COMMERCIAL APPLICATION

The approach taken in Shadwell v Shadwell was subsequently applied in a commercial context in Scotson v Pegg,76 where it was held that the delivery of a cargo of coal to the defendant constituted good consideration, even though the plaintiff was already contractually bound to a third party to make such delivery. It was accepted as good law in the twentieth century by the Privy Council in New Zealand Shipping Co Ltd v Satterthwaite, The Eurymedon.77 Goods were being carried on a ship. The carriers contracted with a firm of stevedores to unload the ship. The consignees of the goods were taken to have promised the stevedores the benefit of an exclusion clause contained in the contract of carriage if the stevedores unloaded the goods. The Privy Council viewed the stevedores’ performance of their unloading contract as being good consideration for this promise. As Lord Wilberforce said:78

An agreement to do an act which the promisor is under an existing obligation to a third party to do, may quite well amount to consideration and does so in the present case: the promisee obtains the benefit of a direct obligation which he can enforce.

3.9.6 PERFORMANCE OR PROMISE?

In all three cases so far considered, it has been performance of the existing obligation which has constituted the consideration. Can a promise to perform an existing obligation also amount to consideration? Take the example used at the start of this section, where A is bound to deliver goods to B on 1 June, and C promises A £5,000 if he does so. We have seen that if A does deliver by the specified date, he will, on the basis of Shadwell v Shadwell and Scotson v Pegg, be able to recover the promised £5,000 from C. What if, however, A also promises to C that he will deliver by 1 June? In other words, the contract, instead of being unilateral (‘if you deliver to B by 1 June, I promise to pay you £5,000’) becomes bilateral (‘in return for your promise to deliver to B by 1 June, I promise to pay you £5,000’). A promises to deliver by 1 June; C promises £5,000. Is A’s promise to perform in a way to which he is already committed by his contract with B sufficient consideration for C’s promise, so that, if A fails to deliver on time, C, as well as B, may sue A? The reference by Lord Reid in the quotation given above to ‘an agreement to do an act’ would suggest that a promise is sufficient, though the facts of The Eurymedon itself clearly involved a unilateral contract (‘if you unload the goods, we promise you the benefit of the exclusion clause’). The issue was, however, addressed more directly by the Privy Council in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long,79 where it was held that such a promise could be good consideration. Citing The Eurymedon, Lord Scarman simply stated:80

Their Lordships do not doubt that a promise to perform, or the performance of, a pre-existing contractual obligation to a third party can be valid consideration.

Given the general approach to consideration, under which promises themselves can be good consideration, this decision is entirely consistent. The law on this point is, therefore, straightforward and simple. The fact that what is promised or performed is something which the promisor is already committed to do under a contract with someone else is irrelevant. Provided it has the other characteristics of valid consideration, it will be sufficient to make the new agreement enforceable.

3.9.7 EXISTING DUTY TO THE SAME PROMISOR

The issue of whether performance of an existing duty owed to the same promisor can be good consideration is the most difficult one in this area. If there is a contract between A and B, and A then promises B additional money for the performance of the same contract, is this promise binding? It would seem that the general answer should be ‘no’. It is normally considered that once a contract is made, its terms are fixed. Any variation, to be binding, must be mutual, in the sense of both sides offering something additional. If the promise is simply to carry out exactly the same performance for extra money, it is totally one-sided. It would amount to a rewriting of the contract, and so should be unenforceable.81

This approach was, until relatively recently, taken to represent English law on this point. The authority was said to be the case of Stilk v Myrick.82

Key Case Stilk v Myrick (1809)

Facts: The dispute in this case arose out of a contract between the crew of a ship and its owners. The crew had been employed to sail the ship from London to the Baltic and back. Part way through the voyage, some of the crew deserted. The captain promised that if the rest of the crew sailed the ship back without the missing crew, the wages of the deserters would be divided among those who remained. When the ship returned to London, the owners refused to honour this promise. A crew member sued to recover the promised money.

Held: The sailors could not recover. There was no consideration for the promise to pay the extra money, as the sailors were only doing what they were obliged to do under their existing contract – i.e. work the ship back to England.

The basis for the decision in Stilk v Myrick is not without controversy, not least because of the fact that it was reported in two rather different ways in the two published reports (that is, Campbell and Espinasse).83 There was, for example, some suggestion that this decision was based on public policy, in that there was a risk in this type of situation of the crew ‘blackmailing’ the captain into promising extra wages to avoid being stranded. This had been the approach taken in the earlier, similar, case of Harris v Watson