Conflict-handling mechanisms in Australian reconciliation*

13

Conflict-handling mechanisms in Australian reconciliation*

Introduction

Legal and political strategies of reconciliation, at this moment in their evolution, are limited by the absence of clearly defined legal objectives and associated implementation strategies. Beyond 2006, what does it mean to take seriously the thought of sharing the legal, cultural and political spaces of Australia between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples? What conflict dispute resolution mechanisms exist in Australian reconciliation?

While much has been accomplished, ideological conflict and disagreement has ruptured the reconciliation process. Government agendas dispute and actively resist legal and political solutions proposed by reconciliation supporters. David Cooper, former National Director of Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR), claims that ‘between 2001 and 2004, many local groups and state peak bodies “lost momentum” and downsized their reconciliation activities’.1 The failure of reconciliation to make even the slightest change to Indigenous poverty, education and health statistics, suggest that conflict and disagreements far outweigh common ground.

Hizkias Assefa, distinguished Professor of Conflict Studies and Peace Building, suggests that ‘compared to conflict handling mechanisms such as negotiation, mediation, adjudication, and arbitration, the approach called reconciliation is perhaps the least well understood’.2 Although the works of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation (CAR) and its contemporary, Reconciliation Australia (RA), have advanced ‘race’ relations, an updated meaning and process to mitigate conflict differences toward reconciliation has not been clearly articulated.

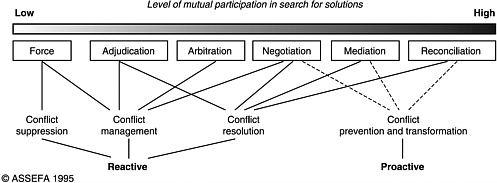

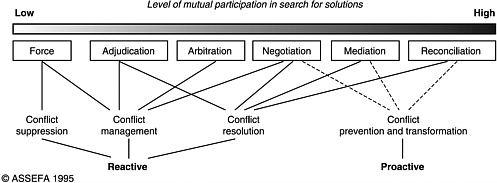

This chapter briefly examines reconciliatory conflict management approaches in Australia, and compares and contrasts them with other approaches used to mediate disagreements toward building coexistence. It draws upon Assefa’s (1999) Spectrum of Conflict Handling Mechanisms as a lens through which to analyse reconciliation in Australia.3

Plotting Australian reconciliation on the ‘spectrum of conflict handling mechanisms’

Professor Hizkias Assefa’s 1999 publication, The Meaning of Reconciliation, constructed a spectrum listed opposite (Figure 13.1) that positions several major conflict resolution mechanisms from the use of force, to reconciliation. The level of mutual participation by the conflicting parties in search of solutions to the problems underlying the conflict is also plotted on the spectrum.4 Plotting Australian reconciliation on Assefa’s spectrum of conflict resolution is used here to examine mutual participation by conflicting parties and to analyse the Australian institutional apparatus used to resolve differences.

Force

Assefa suggests that, at the left end of the spectrum, are approaches where mutual participation by conflict parties is minimal, in contrast to high mutual participation further to the right.5 The use of force by one of the parties to impose a solution would be an example of a mechanism at this end of the spectrum. While Assefa uses the term ‘conflict’ to include civil war within the spectrum, the contemporary Australian context does not involve Statesponsored military force against Indigenous peoples. The circumstance of conflict in Australia is one of passionate ideological, political and legal differences in sharing Australia. It is a conflict that is based on four indisputable facts: First Nations Australia was invaded by the British; no formal agreement or treaty was, or has been, signed; Indigenous sovereignty was not ceded; the social impact of colonisation continues through contemporary disadvantage and injustice. In essence, the Australian conflict between the Indigenous minority and the non-Indigenous majority is played out in political and social arenas to rectify the historical elimination and contemporary denial of Indigenous rights and freedoms.6 It is this definition of Australian conflict that is used throughout this chapter.

Figure13.1 Spectrum of conflict-handling mechanisms.

Adjudication

Further to the right of the spectrum is adjudication. According to Assefa, this mechanism requires a third party to impose a solution to the conflict. Unlike the mechanism of force, the processes of adjudication ‘at least allow the parties the opportunity to present their cases, to be heard, and submit their arguments for why their preferred solution should be the basis upon which the decision is made’.7

In Australia, adjudication mechanisms including the court system have been used extensively since the 1990s to settle disputes over land including Native Title, water rights and the validity of the Stolen Generations policy. But for Indigenous peoples, these have largely been unsuccessful. Indigenous lawyer Larissa Behrendt argues: ‘Indigenous peoples have had disappointing results when seeking redress for rights violations from the High Court and have been directed towards negotiation with the legislature.’8 For example, the failure of the Indigenous plaintiffs in the Stolen Generations case of Kruger v Commonwealth9 highlighted the lack of rights protection via the adjudication mechanisms. Similarly, the 1992 Mabo High Court decision and the subsequent 1993 Native Title Act promoted the conflict dispute mechanisms of the High Court and the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) to determine the parameters of Indigenous property rights. For Indigenous peoples, failure in most cases that have come to the High Court has had a devastating impact. It has invariably meant the extinguishment of Native Title and losing the right to land, with the decision enforced by law. However, in rare cases in which favorable outcomes to both parties can be reached, adjudication can become a conflict resolution mechanism.

Arbitration

Further to the right of adjudication is arbitration. Assefa argues that ‘this mechanism allows both parties to choose who is going to decide the issues under dispute, where as in Adjudication the decision-maker is already appointed by the state’.10 Arbitration is more directed towards negotiation and mediation than adjudication. In this sense, mutual involvement of the parties at least provides the opportunity to select the arbitration umpire to settle the dispute. Here, both parties consent to be bound by the terms within the agreement. As Assefa rightly indicates, ‘although mutual involvement of the parties in the decision making process is much higher than Adjudication, the solution is still decided by an outsider and, depending on the type of arbitration, the outcome could be imposed by the power of the law’.11

An example of arbitration used in Australia is the NNTT, which acts as an arbitrator or umpire in some situations in which adversaries cannot reach agreement about proposed developments (future acts), such as mining.12 The Tribunal also assists parties to negotiate other agreements including Indigenous land use agreements (ILUA). Consequently, the Tribunal engages in mediation, investigation and making decisions (called ‘future act determinations’) in arbitrating conflict disputes around land use and access.

In contrast, there are several aspects that make the popular method of arbitration an inappropriate alternative to the court system for Indigenous Australians. Behrendt argues that ‘arbitration has too many characteristics of the litigation process; is bound by the rules of evidence; and fails to address the power imbalance’.13 Authority and power advantage rests with the adversary that has the most political and economic resources. Such power inequity cannot be underestimated in any conflict-handling mechanism.

Negotiation

Assefa places negotiation further to the right on the spectrum, where mutual participation by both parties seeks solutions that are satisfactory to all in the conflict in absence of a facilitator. Assefa stresses that ‘differences in the power relationship between adversaries need to be considered’.14 For example, the highly resourced nation state has professional negotiators, while litigators for poorer Indigenous minorities are invariably volunteers or earlycareer negotiators who, in general, are outsiders to the community. Assefa and Behrendt are united in their opinion that those who hold power in agreement-making invariably stand to gain more from the negotiation.

An example of negotiation in Australia includes the development of shared responsibility agreements (SRA) and regional partnership agreements (RPA).15 After the bi-partisan decision to close the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in 2004–05, new Indigenous policy instruments of negotiation were developed by the federal Howard

Government. New Indigenous affairs mechanisms were established at the national level to facilitate negotiation including the National Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC) and 30 regional Indigenous coordination centres (ICCs).

The target of these negotiation structure mechanisms involves mediating conflicting differences between Indigenous communities and governments in how to address Indigenous disadvantage at the local level. SRAs involve individual Indigenous communities and governments negotiating solutions, while RPAs involve agreements with a collective of Indigenous groups to bring solutions to a particular region. Negotiated SRAs and RPAs provide modest Indigenous services under the principle of ‘mutual obligation’.16 It is important to note that the negotiation of SRAs and RPAs do not include a neutral third party. All negotiations are conducted within the government corpus through OIPC and ICC, who directly bargain with Indigenous communities at the local level.17 Although SRAs are voluntary, these agreements seek to discharge some government services and responsibility under a bargaining arrangement where Indigenous communities come to the negotiating table to cut a better deal on their health, education and welfare.

Mediation

Mediation according to Assefa is a special type of negotiation within which the conflicting adversaries use a ‘third party to minimise obstacles to the negotiation process including those that emanate from power imbalance’.18 He goes on to state that ‘unlike Adjudication, it is the decision and agreement of the parties in conflict that determines how the conflict will be resolved’.19 Behrendt argues that, because of the use of a neutral facilitator, meditation is better able to redress power imbalances than negotiation.20

The National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (NADRAC) claims that, in recent years, there has been a push in Australia for ADR, particularly in Native Title.21 Similarly, Marcia Langton and Lisa Palmer, in their 2003 paper titled Modern Agreement Making in Australia, claim that the amended 1993 Native Title Act ‘emphasised agreement making as the preferred method of resolving a wide range of Native Title issues’.22 Under the generic title of alternative dispute resolution (ADR), some agreement-making in Native Title is sought through non-adjudicative mechanisms such as mediation, facilitation and negotiation.

One example in the Native Title Act 1993 is the availability of the ILUA. An ILUA is a legally binding contract between Indigenous peoples and governments without the need for a court determination. Langton and Palmer’s paper and the recent Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements (ATNS) project outline other examples of agreement-making in Australia, including environmental agreements, tourism agreements, sea/marine resource rights, joint ventures and small-scale land use agreements.23

Although these agreements are a step in the right direction toward mediating conflict resolution, Langton and Palmer argue that the ‘right to negotiate a limited and prescribed statutory right’ is an ‘inferior substitute for the rights of Indigenous self-government’ preserved in constitutions such as those ‘found in Canada and United States’.24 Nevertheless, they suggest that ‘developments in agreement making are likely to contribute to efforts to improve the disadvantaged status of Aboriginal people’.25 They also believe that agreement-making is an area of policy engagement that encompasses the hard, rather than soft, edges of a meaningful reconciliation process.26

Reconciliation

At the very far right of the spectrum is reconciliation. Assefa argues that ‘this approach not only tries to find solutions to the issues underlying the conflict but also works to alter the adversaries’ relationship from that of resentment and hostility to friendship and harmony’.27 Moreover reconciliation mechanisms for conflict resolution seek to be proactive in anticipating and addressing substantive issues before they surface. Assefa claims that ‘of course for this to happen, both parties must be equally invested and participate intensively in the resolution process’.28

The inspiring stories of South Africa, Northern Ireland and Guatemala reinforce the importance of mutual participation in building reconciliation measures at all levels of government as well as within civil society. Equally, the international experiences in reconciliation building with Indigenous peoples in New Zealand, Canada and the USA are examples where reconciliation makers engage in strategies to transform conflict patterns.

To a certain extent, the establishment of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation (CAR) as a statutory authority in September 1991 was seen as the cornerstone of federal government investment in reconciliation.29