Conceptualizing legitimacy as a target

1 Conceptualizing legitimacy as a target

We can no longer have any illusions on the nature of the principles of legitimacy: they are human, that is empirical, limited, conventional, [and] extremely unstable. Any philosophical hack can demonstrate their absurdity; any dictator, at the head of a gang of cutthroats, can suppress them. Nevertheless, they are the condition of the greatest good that mankind, as a collective being, can possess—government without fear.

(Ferrero 1942: 314–315)

An essential dimension of political struggle, whether armed or unarmed, will inevitably revolve around the power to command and the will to obey since their establishment is what organizes a society. How this is instituted and exercised remains a central and oscillating question for any body politic, and it is surely necessary for a government to manage both elements in order to be defined as functioning. For a community to operate as a unit, decisions and plans must be fixed and then put into action. This clearly requires both command and obedience. Yet, while a commander can be targeted and destroyed with dominant strength, obedience is more elusive and volatile because it is inevitably up to each citizen to exercise this through her own individual will.

As a result, obedience is an element that cannot always be easily explained through the conventional prism of force. There is little doubt that the use of force has commanded compliance time and again. Nevertheless, today it has become clear that access to more powerful weaponry has faded as the primary deciding factor in every political struggle. It is therefore necessary to move beyond notions of pure force to investigate how some tactics applied by the less powerful in armed conflict are intended to achieve victory. Thus, this work will instead examine how the strategic goals of those who utilize terrorist acts might actually be achieved. That is, the aim is to achieve their goals through the provocation of a reaction deemed to be illegitimate since they are clearly not employing overpowering conventional force.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, German sociologist and political economist Max Weber put forward a definition of the state that has become central to Western political thought. Weber described the defining concept of the state as “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (Weber 1946: 78; original emphasis). The thesis of this work will build on what is considered here to be an essential element of this valuable definition: legitimacy. While much attention has been focused on the aspect of physical force found in this definition, the notion of its legitimate exercise is particularly useful for illuminating the line of attack charted by the asymmetrical tactic and strategy of terrorism.

Moreover, it should not go unnoticed that Weber emphasized the exercise of force by a state as the key function tied to its legitimacy. Likewise, this will serve to construct the thesis of this work, as the US wartime authority exercised in the “war on terror” was at times overreaching and in turn became damaging to the legitimacy of the government. Although it is important to recognize that it is extremely difficult to validate any legitimacy claim, one particular moment at which legitimacy comes into sharp focus is when a state’s use of force is challenged. One historical example that has been pointed out is the legitimacy deficit that the US suffered during the Vietnam War. To be sure, many groups that have employed terrorism have raised the legitimacy of the use of force against the people they claimed to represent as central to their grievance against the perceived enemy government (Cook 2003).

Following this same line of thought, the US Army Field Manual 3–24 Counterinsurgency (2006) highlights the centrality of legitimacy over and over again in discussing modern warfare. While this army manual is focused on the use of the US military in foreign territory, and thus at first glance might not seem applicable in this broad conflict of the “war on terror,” one should remember that Al-Qaeda has indeed engaged the US in its own asymmetrical conflict. This means that it is certainly appropriate to classify this group as insurgents attempting to undermine the US government, and, as such, the lessons of counterinsurgency are directly applicable to our discussion. The manual instructively explains,

[i]llegitimate actions are those involving the use of power without authority—whether committed by government officials, security forces, or counterinsurgents. Such actions include unjustified or excessive use of force, unlawful detention, torture, and punishment without trial. […] Any human rights abuses or legal violations committed by US forces quickly become known throughout the local populace and eventually around the world. Illegitimate actions undermine both long-and short-term COIN [counterinsurgency] efforts.

(US Army 2006: 1–24, §1–132)

As we analyze the policies of the “war on terror” in this work, we will find that the exact same examples cited—i.e., the “unjustified […] use of force, unlawful detention, torture and punishment without trial”—became part and parcel of that very policy. The fact that this military doctrine guiding US forces in their overseas campaigns claims that “legitimacy is the main objective” (US Army 2006: 1–21) lends credence to our own theory posited here, and both the coincidence and the divergence will be explored in the next chapter. Once we understand that the actions of government in response to terrorist acts are often directly related to the legitimate exercise of authority and are consequently central to the conflict, the need for more thoughtful and defensive counterterrorism policies becomes imperative.

This concept of legitimacy will be central to our analysis because the exercise of the “legitimate use of physical force” ultimately bears upon obedience to command. It will be posited that those who employ terrorist attacks attempt to achieve their strategic goals by driving a wedge between command and obedience within the enemy society. By provoking an overreaching reaction from a government to deal with the terrorist threat, or by triggering a response that is considered to be outside of the confines of the government’s authority, the intention is that the citizenry of the rival society will deem the actions carried out to be an illegitimate exercise of physical force. If the determination of illegitimacy pertaining to a policy or government becomes widespread—that is to say, that citizens no longer orient their actions in accordance with the authority—then that society is significantly destabilized because it cannot function or move as a unit.

Even before such a drastic state of affairs occurs, a government that has a diminishing pull toward compliance with its authority encounters difficulties. That today’s predominant purveyors of terror wish to immobilize and disorient their enemy to help reach their strategic goals is hardly controversial. In some measure, this will be an explicit conceptualization of what has been broadly suggested by other analysts.

Most importantly, however, the objective of this work is first to illuminate the manner in which non-state actors that employ terrorism attempt to reach their overarching goals through a “strategy of provocation” (Laqueur 1977: 81) meant to target legitimacy. Next, to enrich the discussion of legitimacy, we will present a distinctive way to conceptualize the specific content of legitimacy so that it can be applied as a series of lenses, or tools of analysis, for viewing and discussing this issue. In doing so, it will be possible to highlight the critical role that international law and diplomacy have played in evaluating the overreach in the “war on terror.” With this clarified understanding of the enemy’s strategy for reaching its objectives, we can have a valuable conversation about how a government attacked by terrorism can best defend itself.

To begin our discussion of legitimacy as a target, it is first necessary to explain the structure of this chapter. Partly because of its interdisciplinary nature, it is suggested that the sometimes rigid disciplinary lines of academia have not fostered sufficient attention on legitimacy during times of political struggle. Nonetheless, there are important works that can be utilized collectively as solid building blocks to construct our theory. The question of what makes power legitimate has been of concern for a whole host of professional groups (legal experts, political and moral philosophers, historians, and social scientists, to name but a few) who have approached the subject from diverse perspectives, primarily using their own professional expertise. Yet offering a single disciplinary perspective on the concept of legitimacy can skew and distort this topic of deep complexity. It is therefore preferable to employ an integrative methodology that sheds light on this multifaceted concept so as to overcome a narrower approach. To do so, we will present the pertinent work on legitimacy in a way that recognizes, grapples with, and illuminates the interdisciplinary nature of this concept.

To start, it is helpful to discuss some of the different terms used to describe a research project that is meant to bring together and integrate various disciplines in order to resolve a question too complex to solve through only one field of study. In general, there are three primary terms used to express this type of approach. Multidisciplinarity looks at a topic from the perspective of several disciplines at one time, but makes little attempt to join together their insights and thus is often dominated by the home discipline of the researcher. Interdisciplinarity brings together a collection of viewpoints from various disciplines and then draws on the diverse insights by finding ways to integrate them. The third term, trans-disciplinarity, is meant to capture “that which is at once between the disciplines, across different disciplines, and beyond all disciplines” (Repko 2012: 20–21; original emphasis).

Thus, the first part of this chapter will be organized as a piece-by-piece construction of differing ideas on legitimacy put forward by the most pertinent intellectuals from different disciplines. In this way, it will be possible to see the logic and reasoning for the conceptualization of legitimacy as a target. While there are certainly various scholars who have discussed the concept of legitimacy, its meaning and application have been quite varied. Therefore, there is a limited number of works that are directly germane to our discussion here. As such, we will present the pertinent ideas from authors from different disciplines and allow them to come together in this chapter in what is meant to be an interdisciplinary dialogue.

Sections II–VI will explore the most relevant authors to have treated the concept of legitimacy relative to the context of political struggle. We will start by exploring the literature on the joining of political violence with legitimacy to arrive at the classical works on the subject by sociologist Max Weber and philosopher Jürgen Habermas. Then social scientist David Beetham’s work on legitimacy will be investigated to expose his valuable discussion on power relations and their deterioration. Next, political theorist Hannah Arendt will provide highly beneficial insights on the idea of coerced obedience and its limitations, along with the definition of power as action in concert. The work of international legal scholar Thomas Franck will then present us with constructive language and vocabulary for better understanding the concept of an uncoerced pull toward compliance. With this we will arrive at the historian Guglielmo Ferrero, who will offer an indispensable discussion and imagery that will allow us to put forward our own unique conception of legitimacy as a target of terrorism.

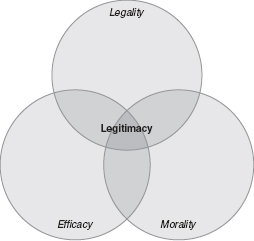

Section VII will then present the logical and necessary next step. That is to say, it will expound on the work of legal philosophers François Ost and Michel van de Kerchove to hypothesize a structure and content for understanding legitimacy in our context presenting legality, morality, and efficacy as the interactive components being targeted by those who employ violent attacks on noncombatants. Next, Section VIII will discuss how the interplay and overlap of these elements can be understood through the work of legal philosopher H. L. A. Hart, along with presenting how the model will be applied in this book in Section IX.

II Political violence and legitimacy: social science and philosophy

There has been general recognition by some social scientists that legitimacy is an important part of the struggle when there is a clash between a government and a group that uses violent actions as their means to engage them politically. In the philosophical literature there have certainly been some attempts to define legitimacy. However, there has infrequently been an attempt to marry legitimation and terrorism in a way that would illuminate the analysis.

Martha Crenshaw edited the volume Terrorism, Legitimacy and Power, which brings together a variety of political scholars to investigate the consequences of terrorism. Of interest for us is that several of the contributors, including the editor, agree that “legitimacy is the key to a successful response to terrorism” (Crenshaw 1983: 147). One contributor focuses particularly upon the tension that is created by terrorism because a government needs to maintain and strengthen its own authority while at the same time diminishing the legitimacy of the terrorists. Hence both effectiveness and the legitimacy of policies are discussed as necessary elements for doing so (Quainton 1983: 52–64).

Accordingly, we find an approach throughout Crenshaw’s book that dovetails with our own judgment that the legitimacy of the policies instituted to deal with a terrorist threat must be constructed with the understanding that overwhelming force without limits can backfire. This is especially the case when all of the culprits responsible for a violent act of terrorism are difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish, track down, and bring to justice. Yet, even though there is recognition in this edited work that “[a]ctions against the terrorists must be scrupulously legal,” combating the threat using similar methods in retaliation is “morally abhorrent,” and that “[e]fficiency and legitimacy […] are closely related” (Crenshaw 1983: 33–35), there is a disappointing lack of effort aimed at giving any real shape to the concept of legitimacy.

Overall, this work by Crenshaw represents the type of attention that the social-science community has given to investigating terrorist attacks in the context of the legitimacy of a regime. One major difficulty for this discipline is that, as recognized by Crenshaw, the legitimacy of a regime is a normative concept and, as such, lacks any scientific metrics, or statistical data, by which it can be adequately measured. Recognizing this truth also means that it is not possible to simply assume that states under attack by terrorist actions, even democratic ones, are to be automatically deemed clearly and perpetually legitimate. This is not meant to suggest that those who employ terrorism have a just cause; it is only an unsophisticated binary framing of the conflict that would lead toward such a conclusion. Rather, it is to point out that the legitimacy of every regime is always in flux and change, and it can indeed be directly affected by terrorism and counterterrorism. Yet beyond this recognition of legitimacy as a normative concept, and pointing to the important connection between political violence and legitimacy, “most social scientists have rarely bothered to discuss the issue at any length” (Cook 2003).

One article that explicitly links terrorism and legitimacy is a piece by the philosophy scholar Deborah Cook, entitled “Legitimacy and Political Violence: A Habermasian Perspective” (2003). The reason she puts forward for writing her article is that “[s]ince political violence today often revolves around the issue of legitimacy, this issue requires much closer scrutiny than it has received in the existing social scientific and philosophical literature” (2003). In Cook’s article, one gets a real sense of how much uncultivated territory lies between the phenomenon of terrorism and the concept of legitimacy. She explains,

because legitimacy is a controversial and complex notion, involving not only legal and political matters, but also more strictly moral considerations, it is probably not surprising that social scientists usually avoid dealing with the issue once they have identified legitimacy as pivotal in the conflict between states and terrorist organizations.

(Cook 2003)

This being the case, in her article Cook does a superior job of outlining the problématique. She identified the current lacuna in the literature and then moved the discussion forward by offering an insightful and pertinent analysis of the work by Max Weber and Jürgen Habermas on legitimacy. In doing so, she places it in the context of terrorism. Therefore, what is necessary for our work here is to highlight the most salient portions of Weber’s and Habermas’s work.

An investigation of Weber and Habermas on the issue of legitimacy presents us with two different approaches that have important impacts upon its treatment. It is necessary to begin by explaining the shortcomings of Weber’s approach, and at the same time justifying the decision to instead follow Habermas on this issue. What we will find is that Weber offers a view of legitimacy that is not amenable to proof, or cannot be tested, because he sees it as based on unspecific subjective beliefs without identifiable content. On the other hand, Habermas adopts the position that the legitimacy of a regime can be accepted or rejected on rational grounds which actually rest on verifiable content that can indeed be tested. As will be seen throughout this book, while legitimacy is multifaceted and ever-shifting, there are some broad lines that can help us come closer to understanding and exploring its essence, even if we cannot know its precise contour lines at all moments and in all circumstances.

Max Weber’s work on legitimacy has achieved classical status in the literature of political science and political sociology, even if it is incomplete. As noted above, the widely diffused definition of the state today comes from Weber when he spoke of “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (Weber 1946: 78; original emphasis). In the same “Politics as a Vocation” speech in which he put this classification forward, Weber stated and then asked,

[l]ike the political institutions historically preceding it, the state is a relation of men dominating men, a relation supported by means of legitimate (i.e., considered to be legitimate) violence. If the state is to exist, the dominated must obey the authority claimed by the powers that be. When and why do men obey? Upon what inner justifications and upon what external means does this domination rest?

(Weber 1946: 78)

Weber goes on to put forward three broad typologies as the “inner justifications” or “basic legitimations,” in an attempt to answer the questions presented here. He presents these as traditional, charismatic, and legal authority: traditional authority is based on a belief in the legitimacy of what has always been known to exist and creates a pull toward obedience out of custom; charismatic authority rests upon the personal magnetism or pull created by the charisma of the person giving the order; and legal authority is based on the propriety of formally enacted rules and statutes. The motivations for recognizing orders or an authority as legitimate will vary, and in individual cases the stimulus to obey will sometimes be combined in differing ways.

However, the thrust of Weber’s argument is that legitimacy is based upon belief. Looking at traditional and charismatic authority, it is quite easy to understand their basic components as subjective beliefs. At the same time, legal authority in Weber’s scheme is at first meant to rest on “rational” grounds, giving a more stable foundation for the critical aspect of the will to obey underpinning a societal structure. Yet further investigation reveals that these “rational” grounds are themselves based upon belief. In his discussion of the three pure types of legitimate authority in The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, similar to what is found in this speech, Weber speaks of “[r]ational grounds—resting on a belief in the ‘legality’ of patterns of normative rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands” (1947: 328; my emphasis). As such, Weber simply assumes that this belief is rational and gives no evidence or support for his argument. Therefore, whether a rule or command is genuinely legal is not determinative in Weber’s scheme, since it is in fact the “belief in the legality” that truly matters.

Also of importance, Weber makes clear that sheer obedience is not enough to signify that the legitimacy has been bestowed from below. Not only must there be identifiable compliance, but this obedience must be willingly given. As Weber explains, “[t]he merely external fact of the order being obeyed is not sufficient […]; we cannot overlook the fact that the meaning of the command is accepted as a valid norm” (1954: 328). Just as we will see in our discussion of coerced obedience and Arendt’s exploration of how violence can at times undermine political goals, Weber too makes the important distinction that to obey out of fear or expediency would not coincide with the concept of legitimacy as discussed here.

Interestingly, Weber follows his discussion of the legitimacy of an order with a section entitled “The Concept of Conflict” (1947: 132–135). Yet although it makes good sense that the legitimacy of a regime would have a direct bearing on the type, frequency, and intensity of social conflict, Weber does not connect the two. He discusses conflict as a battle to impose one’s will that is met with resistance, which can be either peaceful or violent, but he does not address the issue of legitimacy in this discussion. Cook expresses the absence of any deliberation as such,

[t]his omission is all the more surprising because there may be a direct connection between conflict and the belief in legitimacy: when the vast majority of citizens believe in a state’s legitimacy, they will be unlikely to engage in civil or uncivil disobedience. Conformity to laws will generally prevail. Conversely, the weaker the belief in legitimacy, the greater is the potential for conflict. When individuals do not believe that a state’s laws are binding or legitimate, they will be less likely to orient their actions in accordance with these laws, and conflict may ensue.

(Cook 2003)

For whatever reason, Weber does not concern himself with linking conflict to legitimacy.

While it is certainly understandable that Weber would interpret the complex notion of legitimacy as being supported primarily by belief since it is the sum of often tacit actions of many individuals oriented in one general direction, it leaves one wanting more. What is the content of this belief? Is it completely unknowable? Can one count on uncoerced obedience for future order? Perhaps most importantly for this analyst, is there any way to talk about legitimacy with more detail and form? Due to these important questions being left unanswered, Weber’s work on fleshing out the details of legitimacy is not particularly useful when it comes to analyzing it in reference to terrorism.

German sociologist and philosopher Jürgen Habermas holds the very pertinent view that since the grounds of “rational” authority rest on reason, it is indeed possible to test them discursively. That is to say, Habermas believes that not only is it possible to examine the truth claims of a regime’s assertions of legitimacy, citizens in democratic states today do in fact engage in such testing, proceeding by reasoning or argument rather than intuition and belief. This is of direct importance for our analysis since what is being put forward in this book is that legitimacy does have an empirical shape, or a form that is testable with facts, which can be discussed and investigated. Thus, the position of Habermas on this point will be presented here and will then serve as the philosophical basis of moving our work forward on how terrorism targets the legitimacy of a government’s actions in response to the act of terror.

Habermas overtly identifies that it was Weber who was responsible for igniting the debate at a sociological level over the “truth-dependency of legitimations” because of its ambiguity (Habermas 1976: 97). As noted, Weber felt that legitimacy was based on an individual’s subjective belief in a regime’s order or authority, and it was precisely this point that Habermas found to be problematic; if this belief is conceived to be without any inherent relation to truth, then it is only of psychological significance to an individual and not amenable to the testing of rational justification. In other words, the manner in which Weber presented this belief made the motivation to bestow legitimacy of importance only on an individual level, and not something that could be examined by an entire society on the grounds of logic or reason. There can be (and surely are) individual reasons for granting obedience to a regime and orienting one’s behavior in accordance. However, this conception of legitimacy leaves a large swath of intellectual territory that cannot be investigated, and Habermas keenly zeroed in on this shortcoming. To resolve this flaw he instead suggested that the grounds upon which legitimacy rests must be linked to their logical status, and thus they are criticizable because they either do, or do not, “motivate rationally” (Habermas 1976: 98). As Habermas explained it,

every effective belief in legitimacy is assumed to have an immanent relation to truth, the grounds on which it is explicitly based contain a rational validity claim that can be tested and criticized independently of the psychological effect of these grounds.

(1976: 97)

It is suggested here that there are also times when international law can represent this same type of constraint upon a regime because of both international and domestic legal reasoning and because of the fundamental nature of individual protections that can often be easily understood by a population. If we look at the actions identified to be illegitimate in the Army Field Manual overseen by General Petraeus—“unjustified […] use of force, unlawful detention, torture and punishment without trial” (US Army 2006: 1–24, §1–132)—these are extremely important prohibitions which can be found in both humanitarian and human rights law. Additionally, we find these standards frequently discussed in the public diplomacy of the information age. While there is no doubt that there are still hurdles to be cleared for international norms to be generally utilized by citizens in order to discursively test a regime’s legitimacy, this basic practice of legitimacy verification through similar means is relatively recent in human history (Habermas 1976: 86–88). As such, we can understand that the rising use of this tool of holding a government accountable for living up to its constitutional and international obligations surely has ramifications for the policies of counterterrorism. To defend itself against terrorism that is taking aim at legitimacy, a government must take into account the manner in which citizens bestow this uncoerced pull toward compliance.

As such, we find that Habermas takes the salient step beyond Weber to posit that the basis of legitimacy is indeed informed with discernible content. While Weber was satisfied to identify legitimacy as being required by every regime to exercise its authority, he did little to conceptualize it as analyzable, and even less so in the context of political violence that challenges the authority of a government. While Habermas has not delved deeply into studying terrorism in relation to legitimacy problems, he has palpably moved the study of legitimacy and terrorism forward by making their link feasible and reasonable. The two primary forms in which this is accomplished are, first, with his conclusion that “every effective belief in legitimacy is assumed to have an immanent relation to truth” (Habermas 1976: 97) and, second, his finding that citizens (particularly in democratic societies),

as participants in a practical discourse test the validity claims of norms and, to the extent that they accept them with reasons, arrive at the conviction that in the given circumstances the proposed norms are “right.” The validity claim of norms is grounded not in the irrational volitional acts of the contracting parties, but in the rationally motivated recognition of norms, which may be questioned at any time.

(Habermas 1976: 105)

Both of these conclusions are critical for understanding the approach of this book. Like Habermas, we will assume (1) that the legitimacy upon which a regime rests has specific and knowable content; and (2) that citizens can and will test a government’s claims to legitimacy.

It is also valuable to note that this Habermasian approach is being applied at a transnational level by a significant number of social constructivists and theorists of global governance. The work of Ian Johnstone explores the power of legal argumentation within international society and points to the influence of non-state actors as a reason why international law and diplomacy should draw more attention for understanding the operation of the international realm. He also puts forward that the power of the discourse which uses international law and its interpretation is keenly felt “in bilateral and multilateral diplomatic interaction,” and thus we can see how the theory put forward here is useful for diplomats (Johnstone 2011: 8).

There is, nevertheless, one important element put forward by Weber concerning legitimacy that will be central to this study. The particular tack for studying the content of legitimacy claims will be directly related to Weber’s contention that a state is defined by its “monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force.” That is to say, the manner in which the US government exercised its monopoly on force in the “war on terror” as the response to 9/11 will be used as our point of departure.

Although it is very difficult to validate any legitimacy claim, Cook was surely correct in suggesting that legitimacy can become a particularly important issue when a state exercises its use of force or violence. As she explained,

[i]n principle, and to paraphrase Habermas, a state’s claim that its laws and policies—in this case, those authorizing the use of force—are morally justified must be redeemed discursively by citizens. In practice, states have been obliged to demonstrate to their citizens, to other countries, and to the international community at large, that their use of force has been, and continues to be, constrained by just laws, polices, and practices. Where they have failed to do so, their legitimacy has been compromised, sometimes seriously.

(Cook 2003)

III Erosion of power relations: social scientist David Beetham

David Beetham wrote on the subject of legitimacy in his book The Legitimation of Power, and his work offers a perspective that is particularly pertinent to our study. Beetham explores the manner in which a rule or ruler attains and maintains the will to obey and affirms our central contention that study of legitimacy “helps explain the erosion of power relations” (Beetham 1991: 6). This includes both striking breaks in political authority as well as the less dramatic moments of weakness or a diminished degree of cooperation that can be experienced by an authority.

Beetham astutely points out that legitimacy is not an all-or-nothing quantity because it can be “eroded, contested or incomplete” and, therefore, “judgements about it are usually judgements of degree” (Beetham 1991: 20). Thus, when speaking about legitimacy, we are most often discussing the degree of cooperation or the quality of performance. As Beetham explains, “[w]here the powerful have to concentrate most of their efforts on maintaining order they are less able to achieve other goals; their power is to that extent less effective” (1991: 28). Subtle shifts in power frequently occur and might often be explained in other ways. But this does not mean that the dramatic breaches of political and social order, such as riots, revolts, and revolutions, are the only forms of social change related to legitimacy. Put another way, the high level of drama that accompanies such events does not mean that they are the only shifts in power that are worth analyzing and discussing in the context of legitimacy. It is certainly useful to be able to look at and discuss other erosions of legitimacy that occur before there is no longer an intersection between command and obedience. Beetham elucidates the matter by explaining that “[a]s with so much else about society, it is only when legitimacy is absent that we can fully appreciate its significance where it is present, and where it is so often taken for granted” (1991: 6). In full agreement with Beetham, this should not mean that legitimacy can only be discussed when it is absent.

Also of importance is the fact that, although Beetham dons the cap of both social scientist as well as political philosopher and recognizes that both perspectives are valid and treat the issue of legitimacy, in his work he has chosen to approach the subject from the standpoint of the former. Part of the reasoning for this decision is based on his belief that social science has suffered from great confusion on this topic. Thus he wishes to help rescue it from the impact of Max Weber, whose “influence has been an almost unqualified disaster” (1991: 8). As a scholar who has written a treatise on Max Weber, this statement is by no means meant to malign his work or to diminish his large influence on twentieth-century social science.

Instead, Beetham takes issue with the definition of legitimacy that Weber provides in an attempt to avoid making a judgment on its existence in the manner of a philosopher, but instead to present a more scientific report on what is. Beetham, in agreement with what has been discussed above, reduces Weber’s approach to defining legitimacy as a people’s belief in legitimacy. The reasoning for such an understanding is generally thought to be based on a desire to place social scientists at an analytical distance from their subject and not to stand in judgment of a policy or power.

However, the result of basing legitimacy on belief was to make it an individual issue upon which comment was vague or useless for any broader analysis of a society. Beetham strongly disagrees and dissects the impact that Weber’s “belief in legitimacy” has had on social science. Even if it has the laudable goal of insulating the analyst from judging or taking a position,

the whole Weberian theory of legitimacy has to be left behind as one of the blindest of blind alleys in the history of social science, notable only for the impressiveness of the name that it bears, not for the direction in which it leads.

(1991: 25)

To help recover from this impediment that Weber has left as his legacy on the topic of legitimacy, Beetham proposes constructing a tripartite structure of legitimacy that includes differing disciplinary approaches. Beetham is in agreement that the key to comprehending the concept of legitimacy is in recognizing “that it is multi-dimensional in character” (1991: 15). As an attempt to address this manifold concept, Beetham posits that it is necessary to manage its analysis with tools from legal experts, moral philosophers, and social scientists. In so doing, he posits that his framework will allow one to undertake two different tasks. The first is to carry out a systematic comparison between different forms of legitimacy found to be appropriate in varying historical types of social and political systems. Second, the structure hypothesized by Beetham allows the analyst to assess the approximate level of legitimacy present in a given context to help explain the behavior of those involved. Since this second task can be correlated to the gauging of the validity of counterterrorism policy and its effect on a government in relation to its citizens, the fundaments of Beetham’s model are surely worth consideration.

The three primary aspects deemed by Beetham to be the essence of legitimacy can be classified into the realms of the legal, the moral, and the political. Beetham described these categories as operating cumulatively, and on different levels. He explained,

[t]here is the legal validity of the acquisition and exercise of power; there is the justifiability of the rules governing a power relationship in terms of the beliefs and values current in the given society; there is the evidence of consent derived from actions expressive of it.

(1991: 12)

One of the most useful consequences of Beetham’s contribution is that he moves the analyst’s focus of attention away from the consciousness of single individuals. The Weberian approach not only distorted the nature of legitimacy, but it also led to the corrupting of methodological processes of investigation. That is to say, it proposed a flawed research strategy for determining whether a power is legitimate: enquiring whether it is believed to be so. Beetham rightfully insisted that, when it comes to speaking about and analyzing legitimacy, “the evidence is available in the public sphere, not in the private recesses of people’s minds” (1991: 13). If we are to ask the right questions about the acquisition and exercise of power, it is possible to give shape to legitimacy-in-context, and we are not left attempting to compile the opinions of citizens who may or may not understand what legitimacy even means.

Nonetheless, there is one particular criticism of Beetham’s factors of legitimacy. The idea that the power to command must act within rules and processes that have been formally codified and tested through adjudication if necessary is the legal realm that is widely accepted by scholars of legitimacy, including Weber. As well, the view that the rules governing the power relationships within a community and the exercise of power must be found to be justifiable on axiological grounds is also philosophically sound.

However, the theory that the third leg of legitimacy is to be found in actions of consent by the subordinates in a society seems to suffer from the very same flaw of which Beetham accuses Weber; it misdirects our attention away from those who wield power and toward those who are beholden to it. There is no doubt that the actions of citizens, administrators, and military commanders can demonstrate an acceptance of legitimacy. It is even conceivable that these actions are indicative of the fact that the legitimacy of a regime or policy has maintained a certain level that is worthy of note. Nevertheless, it does not speak to the content of targeted legitimacy which we are seeking so as to be able provide an assessment of counter-terrorism policies. The “expressed consent” by subordinates does not offer any substance by which a policy or regime can be tested. Therefore, we will need to continue forward in search of this third piece to the puzzle of legitimacy. Yet for the moment we will set aside this further search for its contents while we provide additional shape to the concept of legitimacy itself in the context of political conflict.