Compulsory Liability Insurance

Compulsory Liability Insurance

9.1 Introduction

This chapter explores the phenomenon of compulsory liability insurance, and its implications. The existence of compulsion plainly demonstrates the significant role of public purpose in securing the satisfaction of tort liabilities through insurance. We have already begun to consider the influence that this tangible purpose may have on judicial analysis of tort claims. However, the desired result is achieved through the insurance market. It is the interaction between tort liability, insurance market, and public purpose that we investigate here.

In the previous chapter, dealing with the role of insurance in shaping tort duties, we largely confined our remarks to ‘novel’ cases, deferring discussion of more ‘conventional’ cases. The relevance of insurance to ‘conventional’ cases has been more hotly debated, and resistance to insurance as a relevant factor has been strong, by reason of focus on the argument—particularly influential in the US—that tort should be analysed as a form of insurance. Responses to that argument deny that tort is simply a gateway to insurance and that liability rules operate on that basis; and (expanding slightly) that liability and first-party insurance should be seen as interchangeable policy options, so that the choices between them (including the choice between tort and insurance measures of compensation) are a matter purely of logic or efficiency. Whatever the cogency of ‘tort as insurance’ arguments,1 we do not propose the reform of tort whether along the lines of a first-party insurance regime or otherwise. Rather, our goal is to explore the part played by insurance in the operation of the law of obligations, and to consider its implications once better understood. At the moment, such an investigation is largely locked out by the strength of normative objections to ‘tort as insurance’, and that poses the risk of misdescription, and hence misunderstanding.

9.1.1 Insurance at the heart of tort liability: ‘conventional’ claims and their operation

Compulsory insurance has a notable effect in relation to what have been called ‘conventional’ or ‘traditional’ tort claims. These have been identified as claims ‘where the defendant’s own positive careless act directly causes physical injury to the plaintiff’.2 In the directness of infliction, such cases are defined as occupied with acts rather than failures to act or to prevent harm. In their focus on direct physical injury, whether to persons or property, they are connected with harm rather than failure to protect or benefit. In both of these respects, the identification of these ‘conventional’ cases is intended to identify the core of the law of tort so that it is distinct from contract.3 One of the reasons for this is to deny a key starting point of influential accounts of ‘tort as insurance’, namely the hypothetical ‘opportunity to bargain’ between the parties.4 The goal is to maintain tort’s distinctiveness in imposing duties (and thus defining wrongs), not sinking into a reflection of party agreement, real or hypothetical. The threat is the ‘death of tort’ through its interpretation as a surrogate for insurance.5 Consistently with this goal, in addition to these hallmarks of ‘conventional’ tort claims, a ‘distinctive’ feature of tort duties is said to be that they are capable of arising between strangers.6

According to this view, the paradigm of tort liability, displaying both ‘conventional’ and ‘distinctive’ features, is a road traffic claim between strangers. Introducing the ‘paradigm tort case’, Stapleton suggested that

[o]ne of the most remarkable features of these cases, such as the pedestrian run down by a careless driver, is that the plaintiff may not even know of the defendant’s existence, let alone ‘rely’ on him in any meaningful sense.7

In its context, this point was made in order to underline that the normal measure of tort damages cannot be said to be a ‘reliance’ measure of the sort encountered (and often described as ‘tort-like’) in the law of contract.8 But for our purposes, it is pertinent that recovery for these very paradigm claims largely depends on an insurance market and therefore on contracting, operating in a heavily regulated form. If we consider ‘reliance’ in terms of a source of protection against risk (a possibility discussed in Chapter 8), it will be clear that claimants in these situations may very well rely upon defendants to carry liability insurance. In a considerable number of jurisdictions, the paradigm has been removed from tort either in part, or altogether.9 Consistently with the fears of those who criticize the ‘tort as insurance’ model, this has generally meant a cap on the damages payable, as the price of expansion in the number of those to whom compensation is delivered.

Since 1930 (in the UK) the apparently ‘paradigmatic’, and certainly routine, liabilities arising from road traffic have been secured through compulsory liability insurance. Public and private law have been combined purposively (though not necessarily always with consistently purposive judicial support) to secure payment of damages. The tort-insurance relationship has created loss-spreading on a significant scale. Just as motor cases constitute the largest single group of tort claims for personal injury, so also payments in respect of motor claims constitutes a highly significant proportion of those made by the UK insurance industry overall, and the single largest line both of accident and of liability insurance.10 As we explain in 9.3, the legislature has been centrally involved not only in requiring such insurance, but in mandating its terms. More recently, EU law has increased the reach and stringency of the applicable requirements. Beyond insurance contracts themselves, different contractual agreements operate to constitute a ‘safety net’, operated by the Motor Insurers’ Bureau (MIB). The ‘hybrid’ (public-private) nature of these arrangements is abundantly clear.

Motor cases combine both ‘conventional’ and ‘distinctive’ features, and in their routine operation between strangers they may claim to be the most distinctive example of conventional tort claims operating on a large scale.11 Where else should we seek the paradigm of tort? In the UK, in terms of volume, a further significant category consists of work accidents. This category too is backed by compulsory liability insurance. And, as with motor insurance, there are many jurisdictions which have departed from tort altogether, and have adopted exclusive ‘no-fault’ schemes. The UK has operated nonexclusive no-fault liability or (more recently) national insurance schemes for such injuries running alongside the law of tort since 1897,12 and although the liability-based regime of workmen’s compensation was abolished in the UK in 1946, no-fault liability for accidents at work remains in common law jurisdictions either the exclusive (as in New Zealand) or the basic (as in each of the Australian states and territories, Hong Kong, India, and Singapore) source of recovery for workplace injuries.

Employers’ liability falls short of the suggested paradigm of tort liability only to the extent that it does not arise between ‘strangers’ (though it might be pointed out that the same is true of a wide range of motor cases). It is therefore ‘conventional’ (provided vicarious liabilities are included in this category), but not ‘distinctive’ in the same way. This is significant to its history: analysis of these liabilities in terms of opportunities to bargain (the rejected starting point for critics of ‘tort as insurance’) was the dominant approach of the common law in the mid-nineteenth century, before (and to some extent even after) the intervention of legislation.13 Though not ‘distinctive’ in this sense, employers’ liability has however been described as more typical of the law of tort in another important respect. In her important critique of ‘tort as insurance’, Jane Stapleton has argued that in terms of the choice between first-party insurance and tort liability (supported by insurance), road traffic accidents may raise unique issues because of the broad-based and reciprocal nature of the risks involved. Historically, including the period when the current road traffic regime was initiated, this has not always been the case as motoring was initially the preserve of a few.14 It may be more broadly the case today, but even so we would need to consider claimants who are cyclists and pedestrians and not at the same time paying motor insurance premiums,15 and—perhaps more significantly—the drivers of public service vehicles excluded from the insurance requirement. If, however, we do accept this as at least broadly the case, then the distributive implications of shifting the cost of insuring to injurer or injured is not strong in motor cases—or at a minimum, not as strong as in certain other instances—because both form part of the same group.16 For these reasons, Stapleton suggested that road traffic accidents are in fact ‘atypical’ or exceptional, and that employer liability and products liability are more typical of tort, in that they involve the infliction of risk on a class of claimants by a separate class of defendants who are, in addition, generally businesses.17 Thus the ‘paradigm’ of tort liability she had identified is conventional and distinctive, but at the same time ‘atypical’.

In the course of this chapter, we take seriously the argument that tort, private insurance, and social insurance may operate to embody different ‘ideologies’ and that choices between them are not merely practical but also ideological.18 Our point, however, is that there is a long history of mixing these solutions. Some have argued that cross-fertilization at the level of legal concepts, no matter how pragmatic the motivations of those deploying and developing those concepts, has deep effects on the conceptual development of the law over time.19 Looking at the core instances in which compulsory liability insurance operates provides a focus for this cross-fertilization and its implications for understanding both liability and insurance. Because the concepts have been mixed so thoroughly, their ideological implications are also fuzzy. In a sense, compulsory insurance—which had been a topic of debate even before liability insurance had spread beyond the marine market20—is merely a reflection of a wider set of policy choices, though it may be found uniquely acceptable by the courts as an admissible point of reference. An implication is that insurance is not to be perceived in ‘conventional’ or paradigm cases, any more than in cases where party risk structures are in issue,21 solely as a matter between the assured, and the insurer. That suggestion is in fact a very long way from the truth.

Although we do not recommend expansion of liability to fit available insurance, nor propose the reshaping of compensation to resemble an insurance market, we disagree with some of the more general remarks of those who have sought to refute such moves. Professor Weinrib has suggested that even those who take a ‘public law’ approach to the issues should ‘feel some disquiet at the intrusion of a mediating factor such as insurance into the plaintiff’s claim against the defendant’.22 As we have seen in the previous two chapters, insurance may not be a mediating factor but the very point of a dispute. One or both of the parties, at least in cases not involving personal injury, may very well be an insurer seeking to place loss elsewhere. That is not a point about public law or even necessarily public interest, but about the law of obligations. But taking into account the prevalence of compulsory insurance at the heart of conventional tort claims, we also depart from his further suggestion that ‘[a] coherent pattern of state action hardly seems likely to emerge from the judicial grafting of a public purpose onto a series of fortuitous relationships between pairs of litigants’.23 In the context of compulsory insurance, and perhaps more broadly, public purpose is not judicially grafted but plainly observable; the identification of a ‘pair of litigants’ may as ever be misleading; but, most of all, the insurance relationship as we will show is very far from fortuitous.

9.2 Significance and Extent

9.2.1 Legislation and liability insurance

Compulsory insurance necessarily represents a legislative choice. Generally speaking, behind the choice is a decision to ensure (to one degree or another) that a person suffering harm receives indemnity or compensation. In the UK, the only existing instances of compulsory insurance by legislation (referring here to private rather than national insurance) relate to liabilities.24 The choice of compulsory liability insurance also amounts in some sense to choosing liability.25 Where liability is delivered through the law of tort and analogous regimes, with the choice of liability comes not only a reliance on breach of duty (defining the risks to be distributed), but also, unless it is adapted by legislation, a choice of the tort measure of damages.

The introduction of compulsory liability insurance, assuming that both liability and the tort measure of damages are to be retained, nevertheless brings with it further legislative choices. Apart from compulsion itself, will further legal resources be deployed to ensure that insurance does mean cover?26 In this respect, a first question surrounds policy defences. As a matter of ordinary insurance contract law, insurers may have one of many defences to a claim, including breach of the duty of utmost good faith, lack of coverage, or failure by the assured to comply with policy terms, and the operation of these defences may remove the source of funds for compensation. An important question is whether legislation allows the insurers to rely upon their defences or whether it modifies rights under the policy so that the proceeds are payable to meet a third-party claim even though they are not so available in respect of first-party loss. Where this occurs, it is plainly a further step away from the idea that insurance relationships are ‘fortuitous’, and that they are a matter between assured and insurer, not concerning the tort claimant. It is a step which has clearly been taken in the UK. As will be seen below, compulsory policies issued in respect of road traffic losses and injury at work both modify policy terms. Partial relief is also given under the Third Parties (Rights against Insurers) Acts 1930 and 2010 to a claimant who brings an action against an insolvent assured when the assured has failed to comply with his post-claim obligations under the policy. The latter point is not confined to compulsory insurance. This in turn illustrates a general point, that legal actors and policy-makers have learned progressively through the interactions of tort and insurance against the backdrop of evolving social policy.27 Component parts of different solutions—themselves sometimes pragmatically oriented to grasping the advantages of existing market responses—have been translated to and absorbed by new contexts, increasing the cross-fertilization to which we have already referred.

A further issue comes into play where liability and a claim under the policy are established, but the assured cannot satisfy the judgment. The issue here is whether the victim can enforce the insurance claim against the insurers. English law, via the 1930 and 2010 Acts,28 confers a direct claim in all cases, and not only in relation to compulsory insurance, although there are special provisions relating to motor vehicle insurance. Here, an innovation which was initially prompted by the move to compulsory insurance has changed the nature of liability insurance in general, recognizing its role in compensating tort claimants, not only in indemnifying assured parties. It takes us a further step along the path away from insurance as a private and fortuitous relationship.

A yet further legislative choice concerns situations where liability is established and where insurance is required to be in place but where, for whatever reason, the insurance is ineffective. That may be because no policy has ever been taken out or because the law allows the insurers to rely upon their ordinary defences in respect of third-party claims and they have successfully done so. The question here is whether some form of fallback fund exists for paying compensation. In England, as regards personal injury and property damage, that is the case only for motor insurance.

9.2.2 Compulsory insurance: the current picture

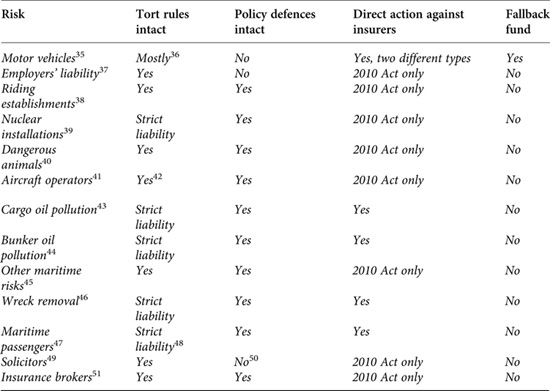

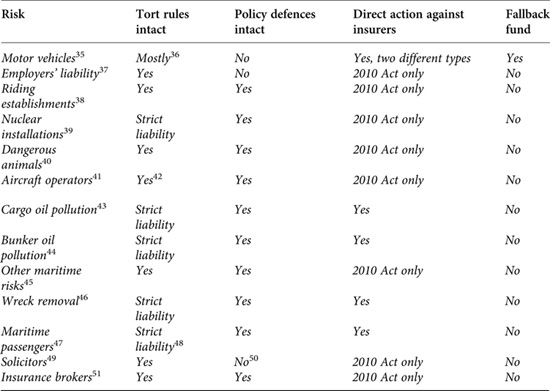

In the UK, it is no exaggeration to say that compulsory insurance plays a central role in the operation of tort law in action. Accidents on the roads account for the vast majority of personal injury claims, and accidents at work though recently overtaken by public liability claims are in third position: both of these are covered by compulsory insurance.29 The large majority of tort claims are met by insurers,30 and most of tort law in relation to personal injuries functions on the understanding that insurance is in place, either because it is compulsory by legislation, or because insurance is known to be routine or required by the rules of professional associations.31 In the current reforms of personal injury litigation and costs, the intention is that 85 per cent of personal injury claims will be dealt with through an extended version of the electronic ‘portal’ which was initially established to deal only with road traffic claims up to £10,000. It is expected that the portal will be extended to employers’ liability and public liability claims up to £25,000.32 Routine, insured liabilities cover the majority of tort claims for personal injury, and these liabilities extend beyond the area of compulsory insurance into the zone of common insurance (specifically public liability).33 So far as the present incidence of compulsory insurance is concerned, and working on the assumption that the 2010 Act will be implemented and replace the 1930 Act some time in 2013 or 2014, the position may be tabulated,34 noting the variables discussed in the preceding section.

There is a rather different form of compulsory insurance set out in the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003, under which tortfeasors are required to pay the costs of NHS treatment incurred by the victims of accidents: if the tortfeasor has a liability policy, then the Act, s 164, implies into that policy a term under which there is coverage for that liability. The insurance device has thus been used to shift the costs of medical treatment from the NHS to the private market. There are other International Conventions which impose compulsory insurance on a strict liability basis with direct claims against insurers—the Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage resulting from Exploration for and Exploitation of Seabed Mineral Resources Convention 1977 and the International Convention on Liability and Compensation in Connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances by Sea 1996—but these are not yet in force. The Health Act 1999, s 9, confers upon the Secretary of State the power to require those providing general medical services, general dental services, general ophthalmic services, or pharmaceutical services to carry liability insurance but that power has not been exercised, although there are statutory schemes for osteopaths52 and chiropractors.53 A similar power in relation to estate agents with regard to client money is dormant.54 The statutory provisions are supplemented by professional rules which require liability insurance to be taken out as a condition of membership of professional organizations, as found, for example, in accountancy. Why then is compulsory insurance so attractive?

9.2.3 Why compulsory insurance?

There is little pattern to the range of duties to insure.55 Apart from international Conventions, which seek to harmonize through minimum standards, compulsory insurance schemes may protect the vulnerable and operate where insolvencies are particularly likely or where confidence needs to be maintained. They are not confined to liabilities in respect of personal injury. Some cover property damage, but a number protect against recoverable categories of ‘pure economic loss’ (particularly in the case of professional advisers of one sort or another). In a general sense, compulsory liability insurance may be thought to have three main strengths. First, it goes some way to ensuring that there is a compensation fund for victims against which claims may be made.56 Second, it protects assured parties from bankruptcy or insolvency. And third, if every person carrying on the relevant activity has to take out insurance, the sums paid by insurers are funded by premiums contributed to by all, so that there is no disproportionate premium burden resting on those who choose to insure. A potential objection—that the deterrent function of tort liability is thereby lost—has little basis and may even be turned into a further advantage of compulsory schemes: where liability insurance is a condition which has to be satisfied to carry on an activity, a bad claims record may lead to a refusal of cover or to unaffordable premiums and thus a loss of livelihood, and the fear of that consequence is no less an incentive to take care than the fear of potential liability faced by an uninsured person. This rationale depends on the market to supply desirable incentive patterns. The potential for this is not confined to compulsory insurance;57 but the need to be insured heightens its likely effect.

Tort backed by compulsory liability insurance, when viewed as a purposive arrangement, is a form of insurance solution. Tort is one of the factors determining what is distributed. In the road traffic context, fault is the gatekeeper, but the process of distribution is indispensable. As currently achieved, this distribution extends beyond the bounds of individual responsibility, and the role of contract in this context is not wholly separable from the objectives of tort nor wholly (even predominantly) a private matter. We say this despite the fact that the measure of damages remains the tort measure, and despite heeding due warnings about treating tort as somehow ‘about’ insurance,58 although we would additionally comment that, but for insurance, many tort claims giving rise to serious injuries would not otherwise be satisfied. Indeed tort claims are frequently compromised at the policy limit of indemnity.59 The present arrangements may simply mark the most extensive form of distribution of the specific risks associated with motoring which are countenanced in the UK.60 In the next section, we examine those distributive arrangements.

9.3 Compulsory Insurance for Motor Vehicles61

9.3.1 Motor insurance and tort liability

As we saw in 9.1, road traffic accidents have been described as the paradigm of tort cases, at least where they occur between strangers. Passenger cases initially tested the depth of the loss-spreading intent behind compulsory insurance, but these and most other issues have gradually been resolved in favour of securing insurance cover. The increasing completeness of the distributive impact of motor insurance is submerged in standard accounts of tort lawyers, and indeed by many critical approaches, both of which focus instead on the relatively orthodox and conventional state of the tort liabilities themselves. Here we show that the distributive impact of the arrangements goes far beyond the portrayal of insurance as merely providing a private route to satisfying conventional tort liabilities, despite the fact that the distributive intent is inevitably limited by the need to establish the relevant liability criteria. An important question is how far these criteria actually function as ‘bargaining chips’ which operate to reduce damages in the process of settlement:62 the issue becomes not so much whether there was or was not causation of harm, for example, but what chance there is that a court would find that there was or was not causation. If that is accurate, then the tort process in this sphere is more thoroughly distributive than so far presented, with a wider distribution of somewhat reduced amounts operating despite the apparent presence of traditional legal criteria. Naturally, insurers are primary among such negotiators, so that actuarial logic is directly connected to the application of tort rules in practice.

Nevertheless, the starting point is that the general tort rules are largely intact in relation to road traffic liability, even if these rules typically do not fall for application by courts but influence negotiation. Few motor cases raise ‘duty questions’, unless there is an attempt to extend liabilities to additional parties (such as public authorities).63 Turning to the standard of care, the courts have held drivers to an objective standard irrespective of whether the driver in question could have satisfied it. This is seen in Nettleship v Weston,64 where a learner driver was held to be liable for injuries inflicted on the passenger (her instructor), on the basis that she had failed to meet the standards of a fully qualified driver.65 The role of compulsory insurance was, other than in the judgment of Lord Denning MR in Nettleship, not explicit in these cases. In the High Court of Australia, Kirby J has recently made the policy reasons explicit, in the learner driver case of Imbree v McNeilly66:

If such compulsory insurance were not part of the legal background to the expression of the applicable common law, and if it were the case, or even possible, that someone in the position of the driver (or the owner) of the vehicle would, or might, be personally liable for the consequences of that person’s driving affecting a passenger (such as the appellant) or other third party it is extremely unlikely, in my view, that the courts would impose on them liability, as in the case of the appellant’s claim, sounding in millions of dollars.

It must be said that in English law, the objective standard itself is well established and of general application, and that it can be defended on grounds other than the existence of liability insurance. But Kirby J’s point remains powerful even so: the operation of the objective standard in the road traffic context, against ordinary individuals in many instances, would have quickly become intolerable without such insurance. It is precisely when tort operates between individuals that it most needs distributive support.

The impact of insurance on tort may also be seen to some extent in the context of defences to tort claims. The defence of ex turpi causa has been applied in motor insurance cases in much the same way as in other cases, and we explore its hidden significance in Chapter 11. The defence of voluntary assumption of risk is removed by the Road Traffic Act 1988 itself: an agreement to exclude liability is void under s 149(2); and the fact that a passenger has willingly accepted the risk of negligence is not to be treated as negativing the driver’s liability under’s 149(3), for example, where the passenger is aware that the driver is intoxicated.67 It should be admitted once again that volenti has in any event become a defence of very limited application in English negligence law.

Contributory negligence was reformed into a proportionate defence almost entirely to deal with the perceived unfairness of the total defence in road traffic claims.68 In this guise there have been some generous decisions involving the victims of motor accidents,69 but there are also contrasting outcomes on similar facts.70 The distributive implications of contributory negligence in this context certainly deserve critical scrutiny. Contributory negligence operates to reduce damages and is particularly susceptible to being applied by parties (mainly insurers) reaching settlements, rather than by courts. Its impact, like that of other legal rules, is not easily charted since settlements are often not itemized.71 It is most likely that contributory negligence simply acts as an additional qualifier on the extent to which full compensation is achieved through settlements, or indeed through court decisions in those instances where a court is involved.72

The more significant changes to tort law in action have come within the law of motor insurance, rather than in the liabilities to which it responds.73 The nature of these changes is entirely unnoticed by accounts which simply assume motor claims are conventional tort claims in which insurance plays a secondary role.

9.3.2 Background to the Road Traffic Act 1988

Although motor insurance was the first compulsory liability insurance in the UK, the scheme had some pedigree. Liability insurance was already being sold to motorists; and this in turn was made possible by the historic creation of liability insurance (outside the maritime context) as a response to employers’ liability risks from 1880 onwards. The way that the legislature dealt with dangers on the roads in 1930 was informed by fifty years of experience of insurance as a vehicle of public policy in the employment context. This included some detailed borrowing of techniques to enhance protection of the injured. In this light, it is not only no-fault compensation that shows the influence of workmen’s compensation (discussed in the next section). Conventional fault-based liabilities also operate with the support of techniques learned from that regime.

The first UK motor insurance policy was issued in November 1896, covering first-and third-party losses arising from participation in the London to Brighton rally, organized to celebrate the passing of the Locomotive and Highways Act 1896. This measure, popularly known as the Emancipation Act, repealed legislation including the Highways Act 1865 which in its original form required any steam-powered vehicle to follow sixty yards behind the bearer of a red flag. ‘Emancipation’ was accompanied by the first recorded fatality, also in 1896. Accident levels reached disproportionately high levels for the number of vehicles. Records were not kept until 1926, but in that year there were 4,886 fatalities and 134,000 cases of serious injury, all arising from only 1,715,421 vehicles.74 The casualty figures had risen in 1929 to 7,000 fatalities and 200,000 serious injuries.

The Road Traffic Act 193075 introduced compulsory insurance into English law, as part of a package of measures designed to improve road safety, including minimum standards for vehicle construction and for roads. A parallel measure, the Third Parties (Rights against Insurers) Act 1930, was passed to support the Road Traffic Act 1930 by giving the victim of a negligent policyholder the right to enforce any judgment against the insurers. This measure is clearly not designed to protect assured parties, and is solely aimed at protecting those to whom the assured is liable. The Third Parties Act 1930 itself ceased to be of significance in motor claims following the passing of the Road Traffic Act 1934, under which the victim of a motor accident was given a specific right to enforce a judgment against the driver’s motor insurers, leaving the Third Parties Act in place to deal with other forms of third-party liability claim.76 The 1934 Act also removed the right of insurers to rely upon non-compliance with claims conditions and certain other policy restrictions where the claim arose from third-party injury, and limited the ability of insurers to rely upon the defence of breach of the duty of utmost good faith, thereby emphasizing the status of insurance as something other than a purely private matter.

The road traffic legislation was reviewed alongside other areas of compulsory insurance by the Cassel Committee in 1937.77 The Committee was appointed to review and improve the operation of compulsory insurance (though it decided that the extension of compulsory insurance, for example to workmen’s compensation as a whole or to cyclists, was outside its terms of reference). It worked on the understanding that the purpose of such insurance was new, and, importantly, that it constituted an exception to the general rule that insurance exists to benefit the assured. It was perceived to be transformative, even if in the context of workmen’s compensation it was hardly a new idea (as to which see 9.4):

Our main recommendations involve a marked departure from the conditions which have hitherto governed insurance business in this country and they are made solely as a result of the special considerations which arise from the element of compulsion.78

The immediate cause for the Committee’s investigation was the failure of several motor insurance companies, and this concentrated minds not only on the need for greater security of insurance; but also on the very purpose of compulsory liability insurance. Plainly, this was primarily considered to be for the benefit of the injured party to whom the assured was liable, and secondarily for the benefit of the assured:

The object of compulsory insurance against third-party risks is to secure that an award of damages to an injured third party is not rendered nugatory by inability to pay on the part of the person responsible for the injury and this object is defeated by failures such as these.79

Three instances of compulsory liability insurance were by then in place, all enacted during the same decade.80 Compulsion was seen as a generic development with important implications. The Committee did not only consider insolvency, but also (inter alia) the effect of policy terms. Here it was particularly clear that the contractual and private basis of insurance had to be rethought in the light of compulsion in support of liabilities. What is interesting is that compulsion came first, and some of its implications were spelled out later—an instance of practice running ahead of theory:

The basis of voluntary insurance is the protection of the insured by means of a contract between himself and the person whom he selects as an insurer; but the person for whose benefit compulsory insurance has been introduced is not a party to the contract of insurance and has no voice in the framing of its terms. It is in the main the securing of protection for a stranger to the contract which has given rise to the problems which we have had to consider.81

The Cassel Committee was not a committee of lawyers, but it encapsulated the necessary shift beyond a two-party frame which much obligations theory still resists. It is often tort lawyers who decline to recognize the extended purpose of contract in such an instance—to secure protection for third parties whatever the intention of the assured.

Pursuing this logic, the Committee made two key recommendations: the extension of the solvency deposit system to motor vehicle insurers (adopted in 1937); and the creation of a fallback fund to pay compensation to the victims of drivers who were uninsured or otherwise unable to recover under their policies (referred to by the Committee as the ‘Central Fund’). This was eventually achieved by an agreement between the government and an industry body—the MIB—in 1946 (now 1999).82 The existence of the MIB encapsulates the hybrid function of insurance under the compulsory scheme: proposed by a departmental committee in order to further the legislative and social purpose of compulsory insurance, it was nevertheless an attraction of the scheme that it would need no government involvement or resources for its operation. This is a counterpoint to tort lawyers’ assertions that the logical conclusion of loss-spreading arguments is that the state should take the burden of the losses: loss-spreading requires resources and organization, and the state will often prefer to allow market actors to achieve this goal.83

The structure established by the 1930 and 1934 Acts and the 1946 MIB Agreement remains embedded in the current governing legislation, the Road Traffic Act 1988. There have been frequent amendments and consolidations. A further MIB Agreement extended compensation to the victims of hit-and-run drivers in 1969 (now 2003). However, the vast bulk of the amendments have been the result of the European Union’s free movement programme; in the context of motor insurance this has led to a harmonized insurance structure for the provision of compensation to the victims of motor accidents. The EU legislation evolved over a series of five Directives between 1972 and 2005, and progressed from an initial requirement of compulsory insurance coupled with the abolition of border checks, an obligation to establish compensation bodies for the victims of uninsured and untraced drivers, single premium coverage for all EU risks, and a direct cause of action against insurers, culminating finally in steps to protect the victims of cross-border accidents. These measures were codified in European Parliament and Council Directive of 16 September 2009, 2009/103/EC ‘relating to insurance against civil liability in respect of the use of motor vehicles, and the enforcement of the obligation to insure against such liability’.

The EU measures have transformed the original concept from insurance against the liability of the driver to insurance against liability arising from the use of an insured vehicle. That is still liability based on fault in the sense that driving has fallen below a relevant standard; but it means that insurance as the source of compensation has been manipulated to extend beyond the reach of personal responsibility of the driver, notably without recourse to traditional ideas of vicarious liability or agency.

The legislative structure is intended to provide compensation in all but exceptional cases (notably those of passengers who consent to be carried in stolen or uninsured vehicles) and it has been necessary to construe the Act in accordance with EU requirements. Together, the legislation does much more than simply make liability insurance for motor accidents compulsory. First, it regulates the terms of insurance policies themselves, preventing insurers from denying liability in given circumstances whatever policy wordings might say. Second, although the 1988 Act and the EU Directives are not designed primarily to affect common law liability rules, they may do so indirectly. But more generally, we can observe a state of affairs where potential gaps in cover have been progressively filled. On the surface, tort appears to remain unchanged; but this is misleading, as notions of personal responsibility are qualified, or recast, in significant fashion.

9.3.3 The obligation to insure

Compulsory insurance entails significant new obligations of its own, carrying the weight of criminal liability in the event of breach. There are two basic strict liability offences set out in the 1988 Act, s 143(1): (a) using a motor vehicle on a road or other public place without insurance or security84 complying with the requirements of the Act; or (b) causing or permitting such uninsured use.85 The term ‘use’ refers to control, generally that of the driver but on occasion a passenger.86 A ‘motor vehicle’ is one intended or adapted for use on roads even though it has some other primary purpose. A ‘road’ is ‘any highway and any other road to which the public has access, and includes a bridge’.87 The accepted view that anything other than private land was a ‘road’ was rejected by the House of Lords in Cutter v Eagle Star Insurance Co and Clarke v Kato,88 holding that a car park open to members of the public and with road signs and markings was not a ‘road’ because it was a destination in its own right rather than a thoroughfare. That curious and non-purposive ruling was rapidly reversed by an amendment to the 1988 Act89 which inserted the phrase ‘or other public place’, a wider term meaning a place to which the public have access.90

9.3.4 Civil sanction for infringement

The 1988 Act imposes criminal sanctions for failure to insure, but it is silent on civil consequences. At a very early stage, in Monk v Warbey,91 the Court of Appeal held that failure to insure was actionable as breach of statutory duty. That was at best cold comfort to the victim of an uninsured tortfeasor, but it mattered where the uninsured use of the vehicle had been caused or permitted by an insured person who otherwise faced no liability for the victim’s injuries. The concept of ‘causing or permitting’ use accordingly became of increased significance as a result of Monk v Warbey, and it is now settled that any person with control of a vehicle who allows another to use it is liable unless an insurance condition is imposed upon the user.92